Well-Being & Ecology _|_ Issue 22, 2022

The Art of Acute Listening

The distinguished osteopath Richard Holding talks about his holistic approach to healing

The Art of Acute Listening

The distinguished osteopath Richard Holding talks about his holistic approach to healing

Richard Holding is an osteopath and teacher whose work is founded on a deep understanding of the world’s spiritual traditions, especially the vision of Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi. Pioneering a holistic approach to healing which is based upon listening to the body, he was instrumental in establishing both craniosacral therapy and applied kinesiology (muscle testing) in the UK. Over the last thirty years, he has trained a generation of practitioners from many different disciplines – doctors, dentists, chiropractors, acupuncturists and homeopaths – in the diagnostic possibilities of the latter. He has recently semi-retired from his highly successful London practice. Jane Clark and Cecilia Twinch talked to him by Zoom from his new treatment room in Bath.

Jane: Most people think of osteopathy as being basically the manipulation of bones. But what you do with your patients is much more than that, I think.

Jane: Most people think of osteopathy as being basically the manipulation of bones. But what you do with your patients is much more than that, I think.

Richard: Well actually, osteopathy was much more than that in its origins, which go back to an American physician called Andrew Taylor Still [/] (1828–1917), who was an evangelical Christian doctor in the late 1800s. He was a preacher as well as a doctor, and he had a spiritual perspective in that he saw that the aim of maintaining physical health is to better serve God. When three of his children died from meningitis, he realised that the current medical model was not working, and he went back to the roots of medical thinking and asked: how can the body teach us to refine the function of our anatomy and physiology so that it can resist trauma and heal disease? That was the original basis of osteopathy. From his spiritual perspective, he saw that the divine creation should be able to be self-balancing and self-correcting to trauma and disease.

But as the treatment became more accepted in America and there were osteopathic medical schools and osteopathic neurosurgeons and such like, it was the biomechanical aspect that got emphasised. Dr Still was very upset by this. He felt that osteopathy had been diminished by trying to be accepted in this way; in fact, he said, I didn’t teach students to push and pull at bones.

However, that is how it developed, and it was how I was trained. I was educated to be a manipulating osteopath in the 1960s. But I became aware in the early ’70s that there were several osteopaths in America who had a different view, and eventually we managed to get them over here to the UK to teach us about the methods they were using.

Jane: One of these was Dr Rollin Becker (1910–1996), I believe, whose father had studied with Dr Still, and who wrote a very influential book called The Stillness of Life [/].[1]

Richard: Yes, he would come over and spend three or four days at our house in Herefordshire and we’d work together on some of my more difficult patients. He did not do manipulation in the usual way, but rather his perspective was to find the innate potential towards normal health in the patient’s tissue.

Cecilia: How did you come to into osteopathy?

Richard: Well actually, it runs in the family. My grandfather – my father’s father – was an osteopath. It is an interesting story. He was a businessman on the Baltic Exchange and he had a bad back. So he used to go to an osteopath, and one day he said to him: “It’s very interesting what you do. If I had my time again, I think I’d be an osteopath.” And the osteopath said to him: “Well, why don’t you?” So he did: at the age of 50 he went back to school and got his A-levels or whatever they had then, and worked until he was 76. Also, I found out later from my mother that there had been bone-setters in her family in Ireland going back 400 years.

As for me: well, initially I trained to be a Catholic priest, and I started to prepare for that from about the age of 11. But in time, I began to feel that it was too restrictive and I left. Nevertheless, my time at the seminary was a deeply religious experience, so when I started to read the old osteopathic literature, it was quite easy for me to see that it came from a spiritual base. Also, in the ’60s and ’70s all of us young people were reading Gurdjieff and Lao Tzu and the Bhagavad Gita and so on. Then I came across the ideas of Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi at the first Beshara Centre, which was at Swyre Farm in Gloucestershire, and it was after that that I really started to be more specific in the way that I applied such ideas to my work as an osteopath.

Jane: You set up a practice first of all in Wales and then later in London?

Richard: Originally in Sussex, in Worthing, and then in Wales. But after a few years the practice there got too busy. There were four of us working together, and over a period from 1973 to 1990 we treated about 10,000 patients; we were bigger than the local GP’s practice! So I moved to London on the basis that it doesn’t have a grapevine and I thought it would be easier to practice quietly. Of course it did not work out quite like that. Now at 75 I am in another phase, wanting to slow down again, and we have moved out of London.

Swyre Farm in Gloucestershire, which was the first Beshara Centre. It was here that Richard first came across the ideas of Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi. Photograph: The Beshara Trust

Craniosacral Therapy

Jane: You specialised early on in craniosacral therapy rather than ordinary osteopathy. Can you explain the difference between the two approaches?

Richard: In ordinary osteopathy, you physically manipulate the body’s muscle tissues and bones, stretching or mobilising them. But in the craniosacral way of working, you just touch the area that is tense or compressed, and in doing so you provide a fulcrum for change and then follow it as it unwinds. So it’s a completely different way of working. In ordinary osteopathy if something does not move you help it, and sometimes even use force to do so. But the other way is to understand that the body could have good reason not to move: it could have a fracture, for instance; or there is an adaptation that has had a benefit for the patient. So by listening and supporting its potential to change, you allow the body to move in its own way.

So there is a philosophical difference between the two techniques, as well as a practical one. Dr Becker’s technique was to use what I call acute listening, which is a way of being what Gurdjieff called ‘actively passive’. Your listening is very intentional, and therefore active; but in your receptivity you are passive, so you’re automatically shifting your intervention according to the changes that are occurring in the patient’s tissues. Another analogy I have used is that of a boat on a river that you want to move; if you kick it you might break your foot or destroy the boat. But if you use the tide, you can just let the boat float quietly along on the water and it will move naturally.

Jane: So you never do any manipulation at all?

Richard: No, it’s all done through touch and what is called proprioceptive awareness – that is, awareness of the position and movement of the body in space. So for example, when I’m working with someone, they might tell me that they experience their feet in a certain way. I am able to ‘scan’ their body and might find that the imbalance at the root of the problem is actually elsewhere. So I can use my awareness of the way the body feels in three-dimensional space to deduce where the problems are.

Cecilia: But the healing does not happen automatically; it usually requires intervention by a trained person. Is this because the person themself is perpetuating their state of disease for some reason, or is it just that the body needs a little bit of help to move to a different state?

Richard: We know that most of the limitations that we have derive from a state of ignorance, and it is just the same with the body. The body has survival mechanisms – ways in which it can deal naturally with the challenges that life throws at us. But sometimes things are too much for it. For example, imagine the case of a four-year-old child who has a virus. The mother does not know that the child is in the early stages of a virus, so she takes them along to the doctor to have a vaccination. And it hurts. Even if there was nothing wrong with the vaccine, the mother had told the child that it would not hurt, to be brave, but it hurt. So the child is traumatised because they think their mother lied to them.

Now they have a trauma, they have had the vaccine and they also have a virus. The body has to decide how to allocate resources in order to cope with these overlapping problems. If there are insufficient resources to fully deal with them, then there will be adaptation – or adaptations – which allow the person’s health to continue. In a way it is a waiting game until there will be sufficient resources.

Now imagine that when the child is a bit older, there is an accident on a swing. They fall off, bang their head and again they have a trauma. So again the body has to allocate resources to deal with it. But if the parents are having rows all the time and the child is stressed because of this, such that their adrenals and such like are affected, then there can be a second layer of incomplete adaptation. By the time we get to old age, we can have 20, 30, 40 layers of these things, and the body has learnt to cope with them in ways that can be quite unhelpful – for example, by drinking too much coffee to compensate for a lack of energy, or alcohol to numb the pain.

Jane: So this is where the ignorance comes in?

Richard: Yes. It requires someone with quite sophisticated skills to find out where the original problems are, and to work back towards that early stage of pure potential that has got modified over the years. And in addition to that, it is necessary to identify where the fulcrum for the change is, in order to clear these layers of adaptation in the quickest way. It could be a matter of nutrition, or it could be homoeopathy, or cranial balance, or whatever.

Richard demonstrating the technique of applied kinesiology. Photograph: Mark Simmons Photography [/]

Muscle Testing

.

Cecilia: You are known not just as a very effective and successful healer, but also as a teacher. When did you start that side of your career?

Richard: My interest has really been in postgraduate education, because when I qualified as an osteopath in 1969 there wasn’t any, which was ridiculous. So I went to the professional body and suggested that they put some on. At first, there was quite a lot of resistance, but gradually it got established. For many years I was on the Osteopathic Board enabling postgraduate education, involved in training not only osteopaths but also doctors, dentists, chiropractors, acupuncturists and homeopaths. And I continue to do this. In the next few weeks, for instance, I will be giving a lecture to homeopaths in London on the effects of viruses on the mitochondria powerhouses of the cell. Alongside the technical content, I always try to drop in some of my philosophical ideas, trying to get people to think slightly differently about healing and the body – without stepping on too many toes along the way.

Jane: One of the features of your work is that you have many strings to your bow; in addition to craniosacral therapy you use other forms of healing – nutrition, homeopathy and, perhaps most importantly, kinesiology, which is a technique that you pioneered in the UK.

Richard: Yes, finding kinesiology – strictly speaking, ‘applied kinesiology’ – in the 1980s was a big step for me. It came about because I started to get patients that did not improve as much as I thought they should. So I started looking at dental influences on the cranium. One of the courses I attended was with a dentist in Las Vegas and he introduced me to kinesiology – or ‘muscle testing’ as it is more commonly known.

Jane: So this is basically a diagnostic technique. As I understand it, the idea is that any issues the patient is experiencing – whether they are structural, chemical or mental – can manifest as muscle weakness. Therefore, by testing the muscles and finding out which ones are not strong, you can identify the underlying problems.

Richard: That’s right. I must say that my immediate response when I first saw it demonstrated was that it was a joke! I watched a patient who was unable to hold up his arm and assumed that the practitioner was just overpowering him. In my undergraduate course, I had been taught that the muscles would be either strong or weak in a structural way, so what he was doing made no sense to me. So I volunteered myself to be the model, and to my horror I realised that he was not overriding me at all. Something was genuinely happening.

So I then persuaded the board of the Postgraduate School of Osteopathy that we should study this approach. I managed to get some of the main teachers of applied kinesiology to come over to the UK – actually, initially from France – to teach the 100 hours of postgraduate training required to properly understand the technique. And that took me into nutrition and homeopathy.

All this was revolutionary within my own osteopathic practice. From this point on, I started to work in a different way, not just prescribing treatments as you would using a textbook – you’ve got such and such a symptom, therefore I will give this or do this to you. Rather, I tried to find a way of using body language – neurology and kinesiology – to develop ways of asking the body how it wanted to change. How did it want to be supported? Where did it want me to start? So from about 1987 onwards I developed ways of working which refined how to read body language so that the body could choose for itself what treatment was most relevant to its physiology.

Cecilia: This kind of muscle testing is very widely used now, at least in the UK. Was what you were doing completely new then?

Richard: In many ways, yes. Some people were using muscle testing to determine the type of treatment, but it was too generalised; they made it a choice between whether to use nutrition or homeopathy, for instance. I am interested in finding a way for the body to dictate the whole progression of treatment. For example, I might ask it whether it wants to start with structural work or with, say, nutrition. If it goes for the latter, then later on, when the nutrition is in the body, it might say: now I could do with some sessions of cranial work. And when that hits a wall, it might need some homeopathy to open up the relevant memory, and so on.

Jane: This seems to be very similar to the work you were already doing with the craniosacral therapy – a kind of more rigorous extension of it.

Richard: Yes, I am convinced that it is just a development of the original intention behind osteopathy, and that if Dr Still was alive now, he would fully approve of my approach – because the whole thing is designed around listening to the patient and finding a place of stillness. In fact, I regard the refinement of this approach as my main contribution to medicine.

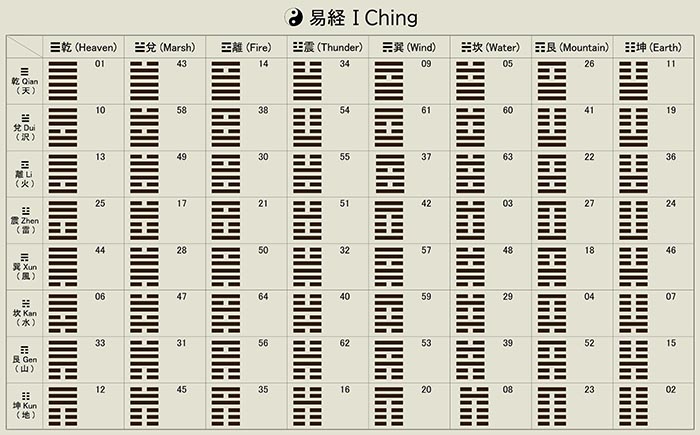

The 64 hexagrams of The I Ching, or Book of Changes. Image: Shutterstock

The Spiritual Basis of Healing

.

Cecilia: What you are doing could be seen either as a science or as an art, or perhaps it is a combination of the two. Inasmuch as it is art, do you see some beauty in trying to restore people to a state of balance or well-being?

Richard: That’s a very good question, because I actually teach my students that if a technique is not beautiful, we shouldn’t use it. The aim is that everything should be beautiful, so if it’s not, and if it doesn’t feel beautiful to work in that particular way with someone, we need to find another approach.

Jane: In what ways do you think that your spiritual education – your study of texts like the Tao Te Ching and the work of Ibn ʿArabi, etc. – has made a difference to your work as a healer?

Richard: I suppose there are several things. One is the idea of having reverence for everyone who comes to see me. It says in the Qur’an – and this is something often quoted by Ibn ʿArabi: Everywhere you turn, there you see the face of God.[3] This is a huge idea. The Christian mystics had the same understanding, but in the modern church it is not emphasised so much. So I try in my little way to develop – and develop and develop – this acute listening, which derives from reverence for the patient.

Jane: Because it acknowledges their innate state of knowledge?

Richard: Yes. And also if we take on board that everything that happens is part of God’s mercy, the role of the physician has to be to tune into that existing movement so that it is expanded and allowed to work more effectively.

The other big influence has been Ibn ʿArabi’s hugely global view of reality – the understanding that everything is interconnected, that everything comes originally from oneness.

Cecilia: In this context, how do you understand the spiritual aspect of healing?

Richard: Well, one way is to use the framework developed within traditional Chinese medicine. This has the idea that we all have early and late heavenly influences. So at conception, when we receive the command ‘Be’ – the command to be brought into earthly existence – the early heavenly chi appears as an organisational energy, and this is always present: meaning, it remains present throughout our whole lives. When the baby is born and the first breath happens, this is the late heavenly influence, which just amplifies the innate breath – the breath of life, this organisational energy that’s always maintaining the person in existence.

So, by tuning into that breath of life which is an innate motion within the body, the healer is allowing the primordial organisational energy to refine the blocks and limited systems which have developed later. These could be limited belief systems; they could be limited biochemical systems; they could be limited emotional systems or trauma. All these things can constitute limitations which make us ill.

Jane: So how do these limitations come about?

Richard: Well, at the beginning, the baby is just pure receptivity; it does not need defence. It is just pure yin, pure being – or we could say, pure potential. But as it comes into the environment of the world, it is subject to all sorts of other influences – from the mother, from society, from trauma. The Chinese call these ‘mundane influences’. These are not essentially a bad thing; I think we’re meant to be exposed to them and we’re meant to learn how to release them, how to see them for what they are – that is, that they are meant to release us from our states of ignorance.

In my teaching, I often use the I Ching to explain this overall movement of creation. Within the Chinese system, what is meant by destiny is that we move away from our pure potential as our energy gets modified by living life on earth and we develop all these limitations and restrictions. But if we take the path of becoming more present – if we work with therapists, or with our esoteric teaching, or whatever – then we can refine our energies, and by the time that we get to cross the Rubicon, which in Chinese medicine terms means that we return to the pure potential – in the terms of western esotericism, it is a realisation of the essential oneness of reality – we find ourselves in the state expressed in Hexagram 2 of the I Ching. This is called ‘The Receptive’ and it is the perfect reflection of Hexagram 1, ‘The Creative’. It is not the opposite, but, as Richard Wilhelm’s translation [2] puts it, the complement of Hexagram 1, through which the creative is completed. In Ibn ʿArabi’s terminology, we would say that it is a state in which we become the perfect reflection of our Lord.

Jane: In my understanding of the I Ching, when it talks about pure receptivity, it does not mean a state of stasis. The underlying principle of the book is that everything is constantly moving and transforming, so what is ideal is more like a state of dynamic equilibrium. Does this bring us back to the idea that illness arises because somehow or other the system is not able to change and adapt in the right way?

Richard: Yes, and this is even present in the word ‘disease’. If you put in a hyphen – dis-ease – it is clear that what is meant is a separation from ease. It indicates a lack of insight into how we survive, and how we learn from being on the planet. For me, the idea of presence – of being fully present in the moment – is at the heart of healing. By working to clear toxins and allergies, by dealing with trauma and re-establishing hormonal balance, and by being as receptive as possible – we become more able to be present. Do you remember Gurdjieff’s second book on his life, which was called Life is Real Only Then, When ‘I am’? [4] – this seems to sum it up.

Richard demonstrating the technique of ‘touch’ which is central to craniosacral osteopathy. Photograph: Mark Simmons Photography [/]

The Healer in Our Times

.

Cecilia: When you’re working with the patient, is it important that they’re consciously aiming for the kind of reintegration you are talking about, wishing to become whole again? Or is it just an involuntary process which can take place on a physical level without much conscious mental participation in the process?

Richard: I think that the healing process is like education. So I don’t feel that I have to lay what I’m doing on the line. But it’s quite interesting to observe that the patients who want to work at the deepest level ‘get it’, without me even having to discuss it. They just feel the change. So I don’t proselytise; I just quietly work, and if they recognise the work at the essential level, then that’s fine. But if they don’t, that’s also fine – and perhaps I’m not then meant to be the person who will act as their fulcrum for change.

Cecilia: You tend to take people for whom other treatments have not worked, so many of your patients are quite seriously ill and are also under orthodox medical care. Do you see your treatment as complementary to this or as an alternative?

Richard: It can be either: it depends on the person. So, for example, if I’m working with someone with cancer, and they have chosen to also follow an allopathic route, then I am complementary, and I would never do anything that limits what the doctors are doing. But if I’m working with someone where everything else has failed – which, as you say, is quite common – then I am their main practitioner. This is why I am still working beyond the age when I might personally wish to retire, as I cannot just leave those patients who rely on me.

Cecilia: Do you find that your own state of being when you are giving a treatment is important? Or is it that, given your many years of experience, it can happen whatever state you find yourself in?

Richard: No, my state matters, and on the rare occasions when I don’t feel well, I don’t treat people. I recently had COVID, for instance, and whilst it was not very serious and I did not take long to recover, I didn’t see patients because it’s too great a responsibility to be working with someone and not be fully present.

Jane: As a final question, I want to ask you whether you see any significant changes in the way people are now, compared to the time when you first started which is now nearly fifty years ago? – apart from COVID, which has obviously been a huge factor over the past two or three years.

Richard: I would say that in general people are more traumatised. They suffer from foods with a low nutrient density and high carbohydrate content, so the quality of the data input into their bodies is getting worse and worse. There are of course lots of people who eat organic food and take exercise and generally look after themselves, but you only have to look around to see that many people aren’t doing this – many of them simply cannot afford to. And then there is the issue of fake news: it is becoming acceptable that people lie in public and just keep continuing the lie, so that in the end significant numbers of people believe it.

These are very difficult times, and it is hard sometimes to keep a positive attitude. But then one has to remember that the beauty of creation always remains unchanged. One of the things I have learnt from the spiritual traditions I have studied is that it is important not to get too involved at the level of politics, but rather, to keep a focus upon the essential and listen to that. I am so lucky that my work is in many ways also my spiritual practice.

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner image: Richard in his treatment in Bath. Photograph: Mark Simmons Photography [/].

Inset: Dr Andrew Taylor Still, the father of osteopathy.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] ROLLIN BECKER, The Stillness of Life (Stillness Press, 2000).

[2] RICHARD WILHELM, The I Ching or Book of Changes, translated into English by Cary F. Baynes (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1951).

[3] Qurʿān 2:115.

[4] GURDJIEFF, Life is Real Only Then, When ‘I am’ (Triangle Editions Inc., 1978).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Ayurveda: A Medical Science Based on Consciousness

How India’s ancient system of healing recognises the unity of the body and the mind

The Healing Power of Plants

Anne McIntyre on the Western and Eastern traditions of herbal medicine, and their importance in the contemporary world

Mindfulness Meditation – Alleviation of suffering for Neurological Conditions

Niels Detert, Consultant Neuropsychologist, explains how meditation can help people with long-term medical problems

Thought for Food

Charlotte Maberly on the new science of Gastronomy

READERS’ COMMENTS

This is a fascinating interview.

Richard’s breadth of vision and depth of insight are truly astonishing.

Thank you Jane, Cecilia for asking some excellent questions and thank you Richard, for answering the way you did!

Very interesting article. I believe in homeopathy, osteopathy and cranial sacral therapy. Since I’ve found these things I’ve been enlightened so much over decades.