Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 12, 2019

Mindfulness Meditation –

Alleviation of Suffering for Neurological Conditions

Niels Detert, Consultant Neuropsychologist at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, explains how meditation can help people with long-term medical problems

Mindfulness Meditation for Neurological Conditions

Niels Detert, Consultant Neuropsychologist at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, explains how meditation can relieve the suffering of people with long-term illnesses

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction was first developed in the 1970s by Professor Jon Kabat-Zinn at the Massachusetts University Medical Center, USA, as a way of helping people suffering from stress and pain. In the last thirty years, it has become a worldwide movement and a wealth of scientific research has verified its effectiveness. In this interview, consultant neuropsychologist Niels Detert talks to Jane Clark about the courses he runs for his patients, the way that meditation changes the brain, and the relationship of mindfulness to its mother tradition, Buddhism.

Jane: What exactly does your work at the John Radcliffe Hospital entail?

Jane: What exactly does your work at the John Radcliffe Hospital entail?

Niels: I am a psychologist specialising in neurological problems. This means that I see people who are suffering from brain damage brought on by strokes or injuries, or by diseases like dementia, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s Disease, and so on. Some of my work is quite technical, in that I do things like cognitive assessments to test memory and attention as part of the diagnostic process, but I also do some one-to-one therapeutic work.

Jane: How did you become involved in mindfulness meditation?

Niels: Back in about 2007, we became aware as a team at the hospital of the great need amongst our patients for some way of alleviating their suffering. We knew that we could not fully meet this need with one-to-one therapy, given the time pressures and the number of patients on our lists. At the same time, mindfulness-based interventions were beginning to become known and talked about in the wider therapeutic community. In Oxford, for instance, Professor Mark Williams [/] had come to the University and set up the Oxford Mindfulness Centre [/], which has pioneered research into the effects of meditation and its therapeutic possibilities.

Before working at the John Radcliffe, I had had many years of education at the Beshara School [/], and my boss at the time, Katherine Carpenter, was aware of this. She knew that I had done some meditation and I had a spiritual practice, so even though she herself did not share my interest, she asked whether I would like to learn this new mindfulness technique, which is officially called Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) [/] or Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) [/].

Jane: I believe that you actually trained with Jon Kabat-Zinn [/], who originally developed this method.

Niels: Yes. First, I did an eight-week mindfulness programme so that I learnt the technique for myself, and then a little while later I went on a short but excellent course with Jon Kabat-Zinn and Saki Santorelli [/] in California. On top of that, Mark Williams kindly included me in some of his sessions at the Mindfulness Centre in Oxford. It was not really enough training by the standards we have today, but I embarked upon delivering my first course at the John Radcliffe in 2009 and it went well enough for us to make the decision to continue. They have been running ever since.

Jane: What do you mean that it “went well enough”? What benefit do people experience?

Niels: The most consistent immediate benefit we find is an improvement in the level of depression and anxiety. And this is exactly what we want to achieve, because if you are less stressed – and therefore less depressed and anxious – you are happier, whatever your other problems might be. In any group with health problems, including cancer, which has been much studied, any reduction in these things can make a huge difference to quality of life.

In a way, what we all want is to be happier. If someone is suffering from a physical condition, then the first way of achieving that is to remove the condition and this is what doctors aim to do. But in some cases, people reach the end of the line medically. The kind of neurological conditions I work with are usually long-term or even terminal; medicine can help manage symptoms but people are still left with significant problems. This can be very dispiriting for them. But with mindfulness training, we can find ways of working directly on happiness.

A mindfulness course at the Oxford Mindfulness Centre lead by Professor Mark Williams (fourth from left, in white shirt). Photograph courtesy OMC

The Structure of the Courses

.

Jane: These courses are for people who have been referred to your department as part of their NHS treatment, and they are completely free of charge?

Niels: Yes. I am part of the Adult Clinical Neuropsychology Service [/], and people are referred through that, sometimes by myself or other doctors and sometimes by the nurses who are working with patients. We initially set up a programme of three courses a year, but over time our referrers have come to value the courses more and more, and our referrals have grown. So a few years ago I was able to employ another colleague, and now we run six courses a year.

We usually have between 15 and 25 participants, and they come with a wide range of conditions – multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, brain tumours, Parkinson’s. We also take people who are suffering from non-epileptic attacks – that is, attacks that look like epilepsy but are in reality due to severe anxiety; another name for them is ‘dissociative seizures’. Because these are so sensitive to anxiety, mindfulness meditation can yield very good results, and although we don’t yet have formal scientific evidence of this, we do have anecdotal observations of substantially reduced seizure frequency in a majority of people who complete the course.

Jane: Can anyone come on these courses, or do you have to be very selective?

Niels: We interview everyone individually before the course. We very rarely turn anyone down, but it does occasionally happen, for instance, if someone is in the grip of a psychotic episode, or a life-threatening condition like anorexia. Meditation is not a first-line therapy for such things, although it might be good later, when the crisis is over.

What is interesting about the group I work with is that many of them have no prior experience or interest in meditation. Some of them have not even heard of it, even though it is quite well known now. What they do have a problem with is their suffering, and what many of them bring to the group is just the raw experience of their day-to-day pain. And they cannot at first see how meditation can be of help to them. One of the delights of conducting the courses is to see how people suddenly ‘get’ the idea – because there is a kind of ‘getting it’ with meditation – usually sometime towards the middle of the eight weeks. When this happens, people’s perspectives can really transform, and they are able to manage their condition very much better.

Walking meditation at the Brahma Vihara Aramo Buddhist Monastery in Lovina, Bali. Photograph: Craig Lovell/Eagle Visions Photography/Alamy Stock Photo

Jane: Can you say something about the form of the courses?

Niels: They are taught as an eight-week group course in weekly two-hour sessions (we actually do two and a half hours) with guided meditation and discussion. Participants also do 45 minutes a day of home practice using audio-guided meditations. In addition, on many courses, there is one full day which is done as a silent practice. I started by teaching MBSR, and now I do MBCT, which includes some cognitive therapy elements.

A variety of forms of meditation are used, such as: sitting with awareness of breathing; mindful yoga; walking meditation; body scan meditation, which is the practice of sequentially paying attention to different body regions and using body sensations as the meditative object. But all involve the same principle of paying attention, moment by moment, on purpose and non-judgementally, to experience as it is.

Jane: Have you had to adapt the course for your particular participants?

Niels: Not much, although of course we have to make some adjustment for physical disabilities. The only part which addresses the particular concerns of this group is the so-called ‘inquiry’ – the semi-structured, semi-improvised conversations between the practices. This is the part I myself found initially most challenging. The practices themselves are relatively straightforward after a bit of training, especially if you have a practice of your own, but the skill of leading the open-ended discussion is more demanding.

So at the beginning I had to rely very much on my previous training at the Beshara School, and particularly on what I had learnt about the art of conversation – listening and responding to the unfolding discussion in whatever way came to me, and of course relying on my clinical psychological and therapeutic skills. And that seemed to work.

Jane: You have mentioned the improvements in patients suffering from dissociative seizures. Do you see physical improvements in other conditions?

Niels: We would not expect to see improvement in the disease process as such. But it is also true that some of these processes are sensitive to stress, so if you can reduce that, there can be an impact on physical symptoms. This seems to be the case for multiple sclerosis. We don’t have any specific, quantitative evidence that mindfulness training – or any other stress reduction technique – has an effect on the development of the disease, but anecdotally that is what the patients describe.

But on the whole, we are not talking about physical cure. We are talking about a better quality of life, better management of symptoms. People also come to know their bodies better, and become better able to distinguish between the effects of stress and the effects of the disease and so are able to manage these better.

Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard is prepared for a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) test at the MRI facility in the Waisman Center [/] at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, with co-principal investigators Professor Richard J. Davidson (centre), Antoine Lutz (right) and technician Michael Anderle (left). Ricard is a long-time participant in a research study led by Davidson that monitors the impact of meditation on pain regulation. Photograph: Jeff Miller

The Scientific Basis

.

Jane: You have mentioned scientific studies, which are very important these days given our evidence-based approach in medicine. Have you done any formal research on the effects of your courses?

Niels: I have published one study, in 2014, based on results for 98 people. [1] We used questionnaires which aimed to measure stress reduction, depression and anxiety, because, as I said, this is one of the main aims. The results were in keeping with the rest of the literature on mindfulness; they showed a medium effect size in reducing psychological symptoms – depression, anxiety and so on – and a very large effect size in improving perceived stress. By ‘medium’ we mean half a standard deviation or more, and by ‘large’ about 0.8 of a standard deviation or more. Ours was an uncontrolled study (without a control group, so not very rigorous), but these kinds of effects are borne out by more sophisticated studies using randomised controlled methodology.

Jane: Can you explain why mindfulness meditation – which is basically, as the name implies, about developing awareness – should lead to this large reduction in perceived stress, by which I am understanding that people feel much less stressed?

Niels: It means that they feel better at managing stress. They are more confident that they can deal with the stressful situations of life.

What people practice on the course is the process of becoming aware of what is going on – in their lives, in their bodies – moment by moment. Things constantly happen to us, and without mindfulness training, we tend to react to these events in a habitual way – that is, emotionally. And this reaction includes within it the assumption that what is coming at us is real.

But the alternative to this is to be aware: aware of what is happening; aware of our own emotion; aware that at least some of the apparent awfulness that is coming at us – whether it is a bill, or something in the news, a physical pain or some new development in our physical condition – is augmented by what is in our own mind. If I am aware of these things, I can observe the emotion and see it as just an emotion; I can see the thoughts and not take them as entirely true. And I don’t have to do anything about those thoughts or emotions; I can just observe them and so I am less affected by them.

Then I can walk away from this situation and think – well, next time I will be able to do the same thing. So I feel more confident that I can deal with whatever may happen in the future.

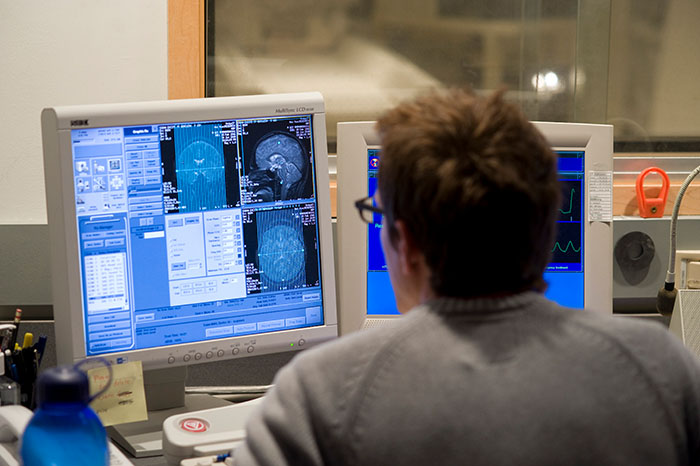

Technician Michael Anderle monitors computer displays as Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard participates in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) test at the MRI facility in the Waisman Center [/] at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Photograph: Jeff Miller

Jane: I understand that we can actually see changes in brain function on MRI scans and such like.

Niels: Yes, there is a large body of work now that shows us that meditation actually changes the configuration of the brain. But actually, we should not be surprised by this, as anything we learn changes the configuration of the brain. We know that London cab drivers [/] who acquire ‘The Knowledge’ show an increased development in the hippocampus, and that Einstein’s violin playing [/] resulted in a ‘bulge’ in the area associated with the movement of his left hand. What is more interesting is the detail; seeing what areas of the brain change.

One of the most interesting things we learn from the scans is that the effects of meditation are cumulative; the more training you do, the more effect it has and the more the brain changes. For example, we see increased grey matter volume in areas exercised by the meditation. If you look at people who have done an eight-week course, there is a certain effect, but if you look at people who have done 1,000 hours, which is probably several years, then there is not only a larger effect in these areas, but also a different pattern of activity [/]. [2]

Jane: In what way?

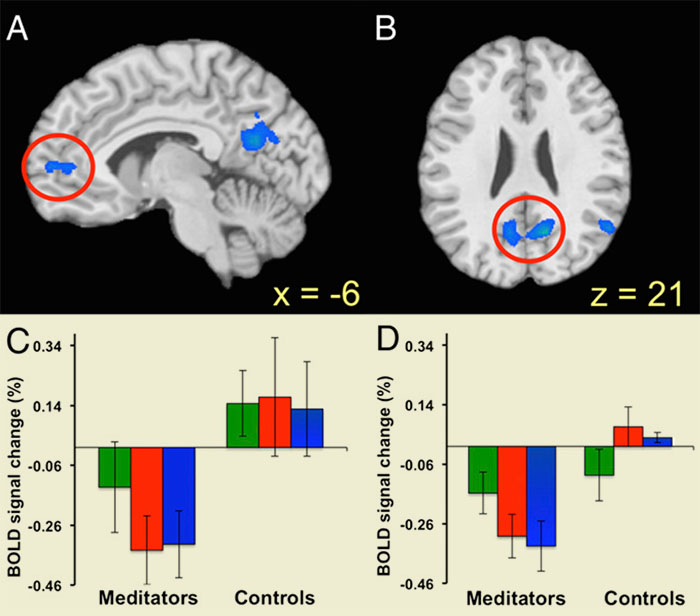

Niels: We can look at people’s brains in scanners and watch what happens when they are meditating or when they are not meditating. When you look at people who have done just a few hours, we see a reduction during meditation in so-called ‘default mode network’ activity; that is, in that network of brain regions associated with day-dreaming, mind wandering and self-referential rumination.

But when we look at people who have done a lot of training, it seems that the pattern of changes in brain activity associated with meditation have not only become stronger; they are also generalised to the non-meditative state. This means that there is reduced activity in parts of the default mode network activity associated with self-referential processing even when not meditating.[3] So the neural correlates of the meditative state have become more trait-like; or we could say that the ordinary state has become more mindful.

We also see that in the early stages of training there is a lot of activity in areas associated with effort during meditation, whereas with more training, it really seems to become more effortless. [4]

Jane: This is interesting, as it is very much the aim within the spiritual traditions that the practice of prayer and remembrance, which is so difficult at the beginning, should eventually become, as it says in the Rule of St Benedict:

sine ulla labore velut naturaliter

“without effort, as if naturally”.

Niels: We find similar sayings within Buddhism. I think this is very important in the teaching of mindfulness. At the beginning, it is only natural that people exert a lot of effort; they are learning something new, and they think the task is to pay attention to some aspect of their experience or bodily sensation. So they try very hard to concentrate. But this is actually not the ultimate idea; the idea is to become more aware in general, and during the course we hope that people will start to learn this and relax into awareness. What is aimed for is the natural awareness that we all have anyway when we are sitting and talking and listening to each other, and to be aware of being aware.

Brain scans showing the contrast between experienced meditators and beginners in the medial prefrontal cortex (A) and the posterior cingulate cortex (B). Three kinds of meditation were investigated: choiceless awareness (green); loving kindness (red) and concentration (blue), revealing a significant reduction in default mode network activity for experienced meditators in most conditions in these areas (Graphs C, medial prefrontal cortex; D, posterior cingulate cortex). From Brewer et al, 2011 [3]

Secular or Spiritual?

.

Jane: One of the controversies concerning mindfulness is that its roots are in the Buddhist tradition, where it would have been done as just one aspect of the eight-fold path. So it includes ethical considerations – right view, right resolve, right livelihood and so on. And you yourself have now embraced this tradition. Do you think that it works to just use the bare practice, without the metaphysical or ethical framework?

Niels: Well, yes, I think it does. For one thing, conducting these courses in a medical context within the NHS, it is not possible to frame them within a religious or spiritual context, as the people attending might come from a variety of faiths or spiritual paths, or they might not have an explicit faith at all.

But it is also important to say that mindfulness as it is taught on these courses is not completely severed from its roots. We talk about kindness, for instance, both to ourselves and to other people. This is implicitly there because paying attention to ourself in a non-judgemental way is one of the kindest things we can do for ourself, but this aspect is also drawn out by the person leading the group. You cannot really have mindfulness practice without an element of compassion.

This is not an ‘added-on’ aspect because fundamentally, our human nature is both aware and compassionate. This is what we are told by Buddhist masters, or indeed, by the masters of any spiritual tradition, and this nature is there to be discovered by anyone, whether they think of themselves as engaging in a ‘spiritual’ activity or not.

Jane: And what about the leader the group? How important is their knowledge of the wider aspects of the tradition?

Niels: I think it is true that, in one way, a mindfulness practitioner who teaches within a purely secular context is missing a dimension. Their intention would perhaps be more to do with reducing individual suffering and, unlike a teacher with a Buddhist background, they would not have the idea that what we are aiming for is liberation from all suffering for all beings, or that compassion extends to all beings. But in another way, there is no absolute limit on secular mindfulness practice, because the person who is doing the meditating has this fundamental human nature, which is universal. So potentially they can discover that within themselves, and they can be guided by it.

In fact, they certainly are guided by it as they start to grapple with things on the course – with their experience, with their thoughts, with their bodily sensations. And the fundamental touchstone is something like: when I find myself being a certain way, doing a certain thing, how does that work out? How does it work for me, or for other people? So the touchstone is some basic sense of compassion or kindness or justice that we all have.

Jane: You raise an interesting point. For a lot of people these days, religion or spirituality is seen as a kind of brainwashing – taking on a set of beliefs or practices which turn us into a different person. But you are pointing out that the essence of any true practice is that we become what we already are.

Niels: I think it is very helpful for us to draw on the wisdom and guidance of people who have gone further than us along the path. This is why I myself have become involved in the Buddhist tradition in terms of reading more about the metaphysical context, undertaking the practices, and attending teachings with great masters. But I see my involvement like this – it’s not that I have ‘become a Buddhist’. So I believe that whilst knowledge of Buddhism can be very helpful in deepening our understanding – and it is still a required component on the teacher training courses – it is nevertheless not absolutely necessary.

Jane: And if one is looking for a spiritual context, it is not only Buddhism that is relevant. People are now making connections to the Christian tradition. In fact, Mark Williams, who has done so much for the mindfulness movement, is also a Christian priest.

Niels: Yes indeed. I have a friend here in Oxford, Tim Stead, a priest who ran mindfulness groups at a local church and has trained as a mindfulness teacher. He has written two books: the first is Mindfulness and Christian Spirituality,[5] addressed to Christians; and the second is See, Love, Be: Mindfulness and the spiritual life,[6] aimed at a more general audience. What can be drawn out by this kind of connection is the more contemplative side of Christianity, which has not always been emphasised in the past.

Seated Buddha statue made of stone in a meditation posture, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka. This beautiful ancient city was a source of inspiration for Thomas Merton, a modern representative of the Christian contemplative tradition. See Jim Griffin’s article in Beshara Magazine. Photograph: imageBROKER/Alamy Stock Photo

Suffering as a Human Condition

.

Jane: You have already mentioned the personal challenge presented by the ‘inquiry’ parts of the course. These sessions must be especially interesting given that the people you are working with are facing such essential problems. I am thinking especially about those people who have terminal illnesses.

Niels: Actually, it was with the brain tumour patients in mind that I started doing these courses. I thought that mindfulness would help people discover a way of facing death. In fact, I mentioned this to Jon Kabat-Zinn on my training course, and he accepted it. But he came right back to emphasise the people who are suffering because of their physical problems right now, in life. And he was right; this has proved to be the main focus of questions. Even those people with brain tumours are predominantly concerned with the immediate challenge of how to live with the difficulty of their condition, the emotional ups and down, the daily stresses. The most common thing that comes up in discussion is how to deal with pain, which is an enormous problem for many of my patients, particularly people with multiple sclerosis.

Jane: MBSR was first developed, of course, by Jon Kabat-Zinn, specifically as a way of helping people to deal with chronic pain.

Niels: And it is very effective. In fact, I would say that mindfulness meditation is really a very good solution for people suffering from long-term chronic conditions where there is no medical cure.

However, a conspicuous absence on the mindfulness course is the lack of any questioning at all about the reality of the self. Or it may be better to say, “questioning the nature of the self”. We don’t do that, at least not explicitly. This is one big difference between working within a mindfulness context and within a spiritual tradition – at least, within the two traditions that I have been involved in.

Jane: You are referring, I assume, to the concept within Buddhism of the ‘emptiness of self’ (sunyata) – the idea found within all the spiritual traditions, if you look deeply, that the self is essentially non-existent, or that it is a kind of illusion. Why do you think that the mindfulness programme does not tackle this?

Niels: I don’t know. I think that discussion about this could potentially be quite anxiety-provoking, rather than anxiety-reducing, and it is something that many people would not easily be able to understand as beginners in meditation and without a metaphysical context. But without this kind of discussion, it is very difficult to develop a different perspective on death. The concept of impermanence would perhaps be a good way into the matter, as this would not be too personal.

Jane: I must say that I am surprised that the level of problems these people have can be accommodated within the standard course format. It is another indication, perhaps, that these exercises are addressing something very fundamental in us as human beings.

Niels: Of course, there have to be physical adjustments sometimes. Someone with advanced Parkinson’s cannot do a twenty-minute walking meditation, and we have to take precautions for people who might have a seizure during the group, etc. But fundamentally, it all comes down to the same problem: we are all suffering. How do we deal with that?

Jane: Do you know what happens after the course? Do people go on to establish a long-term practice?

Niels: That is the ideal situation, which of course we encourage. And some people do. Some even go on to engage with Buddhism or other spiritual traditions. But others do not practice at all after the course ends, and the situation for most people, I expect, is that they continue to meditate to some degree. But I am quite sanguine about all this: I think that people use what they need to. For some people an eight-week course reduces their depression and anxiety sufficiently to get them out of a hole, and that is enough for them. Although having said all that, I think that we could probably do more to follow up and give support to those who want to continue.

Jane: So what next? Are there new developments in the offing?

Niels: Well, basically, we are planning to continue our six courses a year at the hospital. The new development is that we are setting up an on-line course so that people who cannot physically attend the John Radcliffe can still participate. This will also be useful to people who attend the course in person to supplement their learning if they want, or if they miss a session, or want to review some of the material after it is over. It is also likely to be available to the general public who may happen to find it online. We are in the middle of doing the video and audio recordings for that, and that is quite exciting.

For further information on mindfulness courses run at the John Radcliffe Hospital, please contact russellcairns@nhs.net

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner picture: Niels Detert in his office in the Russell Cairns Unit, John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford. Photograph: Jane Clark.

First insert picture: The new West Wing of the John Radcliffe. Photograph: Oxford Photography Project/Alamy Stock Photo.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] DETERT, N., DOUGLASS, L.: “Mindfulness MBSR/MBCT in a UK Public Health Neurological Service: Depression, Anxiety, and Perceived Stress Outcomes in a Heterogeneous Clinical Sample of Ninety-eight Patients with Neurological or Functional Neurological Disorders” in Neuro-Disability and Psychotherapy, (2014) 1–2, pp.137–56.

[2] MARION SPOON: “Meditation affects brain networks differently in long-term meditators and novices” in University of Wisconsin-Madison News, July 2018. Click here… [/]

[3] BREWER, J.A., et al: “Meditation is associated with differences in default mode network activity and connectivity” in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 13 December 2011, 108(50), 20254–9 .

[4] ZEIDAN, F.: “The neurobiology of mindfulness meditation” in K.W. BROWN, J.D. CRESWELL, & R.M. RYAN (eds.): Handbook of mindfulness: Theory, research, and practice, New York: The Guilford Press, 2015, pp.171–89. Click here… [/]

[5] TIM STEAD: Mindfulness and Christian Spirituality, SPCK 2018.

[6] TIM STEAD: See, Love, Be: Mindfulness and the spiritual life, SPCK 2016.

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Ayurveda: A Medical Science Based on Consciousness

How India’s ancient system of healing recognises the unity of the body and the mind

The Engaged Contemplative Spirituality of Thomas Merton

by Jim Griffin

READERS’ COMMENTS

As

Time stands still

Peace reigns supreme

Love seeking Its own

Truth as dimensionless Being

Charles Mugleston

This is a very profound and inspiring interview with Niels.

Thank you very much.