Well-Being & Ecology _|_ Issue 15, 2020

The Healing Power of Plants

Anne McIntyre on the Western and Eastern traditions of herbal medicine, and their importance in the contemporary world

The Healing Power of Plants

Anne McIntyre on the Western and Eastern traditions of herbal medicine, and their importance in the contemporary world

Anne McIntyre [/] has been practicing herbal medicine for nearly forty years and through her many publications and lectures has gained a worldwide reputation for the depth of her knowledge in both the Ayurvedic and Western traditions of healing. She is a fellow of the National Institute of Medical Herbalists, a Member of the College of Practitioners of Phytotherapy and the Ayurvedic Professionals Association. Elizabeth Roberts, herself an Ayurvedic herbalist, and Jane Clark met her at her practice in Gloucestershire, UK, to ask her about the unitive principles behind her work, and how knowledge of the extraordinary qualities of plants can help us to develop more sustainable lifestyles in the face of climate change.

Elizabeth: You are both a medical herbalist and an Ayurvedic practitioner. How did you become interested in Ayurveda?

Elizabeth: You are both a medical herbalist and an Ayurvedic practitioner. How did you become interested in Ayurveda?

Anne: Actually, my interest in Eastern philosophy came first. When I was about 16, I read a book called The Wisdom of India [1] and learnt all about the Vedas and the Upanishads, and such like. I started to practice Buddhist meditation and then, between school and university, I went overland to India. My aim was to become an enlightened being, and I thought that if I meditated enough every day, I would be able to achieve realisation by the time I was 30 – which, at that age, seemed a long way off!

When I came back from India, I went to university to study Oriental philosophy, but I found it boring in comparison with the things I had experienced in the East. I only lasted six months. Instead, I became interested in the concept of self-sufficiency; I read John Seymour’s books [2] and Richard Mabey’s Food for Free [3], all of which were very popular in the 1970s. And this led me to take a house on an island off the coast of Essex where I began experimenting with growing vegetables and foraging for wild herbs and foods.

It was at this point that I had an important realisation about nature and our relationship with the world around us, and also the healing power of plants. I began to see that they are not just food but amazing medicinal resources which have the power to heal us at every level of our being.

Elizabeth: So was this what motivated you originally to train as a herbalist?

Anne: Yes, it took me, eventually, to study herbal medicine and then, once in practice, a whole range of other healing techniques: massage, aromatherapy, homoeopathy and counselling. It was actually much later – in about 1987, when I had been practicing for some time – that I heard about Ayurveda and was interested because it seemed to bring together a lot of other things I had been doing in my practice, including Eastern philosophy.

Shatavari (asparagus racemosus) root is sweet and warming. It decreases vata and pitta and increases kapha. Photograph: wasanajai/Shutterstock

Working with Energies

Elizabeth: What difference has the knowledge of Ayurveda made to your practice?

Anne: In general, I would say that the main effect has been to make my clinical work much easier. Ayurveda is tailored to treating each patient constitutionally. Using the Western tradition, if I saw a patient with, for example, arthritis, and they didn’t respond to the herbs I prescribed, it could be confusing, especially if other patients with the same problem had responded well with a similar prescription. With Ayurveda, I can choose remedies and recommend lifestyle changes according to the constitutional balance or imbalance of the patient.

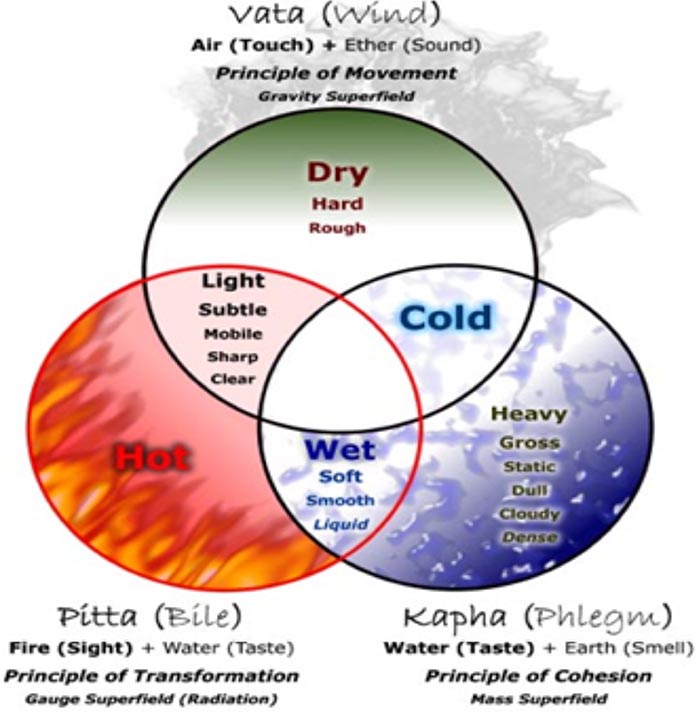

All forms of herbal medicine – whether they are Western or Eastern – are holistic, which means that we don’t treat symptoms: we treat people. Somebody may come with a whole range of symptoms; they might have insomnia, migraines, night sweats, colitis and stress. In this instance, there would seem to be five different things going on. In Ayurveda what we look for is the underlying state which causes these different problems, and this means working with what are called the ‘doshas’. These are the subtle energies of the body – the managers of all processes at every level, physical, emotional and mental. There are three of them: vata, pitta and kapha. (See Elizabeth’s article “Ayurveda: A Medical Science Based on Consciousness” in a previous issue.)

Jane: And each person has a different natural balance of these?

Anne: Yes. The first task when we start a course of treatment is to establish the basic constitution of the person – meaning, what is the balance of their vata, pitta and kapha. This is known as their prakruti. It is what they inherit from their parents at the time of conception; it is influenced by the 40 weeks gestation period and established at the time of birth. I call it ‘their gift for life’. You ascertain the prakruti by taking a case history and examining the patient, as in tongue and pulse diagnosis.

Then it is important to understand how a person has moved away from their basic constitution, and what their doshic balance is now; this is known as their vikruti. Finding out which doshas are out of balance will allow me to suggest a protocol, including herbs and changes in diet and lifestyle, which will bring them back to health.

The doshas

Jane: Can you say more about these doshas? What does it mean, for instance, to say that someone has a predominance of vata?

Anne: Ayurveda is five-element medicine; the understanding is that we are all made up of ether, air, fire, water and earth, and they make up the three doshas. Vata is the principle of movement. It is composed of ether and air, so it is subtle and mobile and it governs every movement in the body: the transmission of nerve impulses; the blinking of the eyes; the movement of food through the digestive system, etc. The quality of the movement could be a gentle breeze or a force eight gale, and this means that those with a predominance of vata in their constitution tend to be erratic and irregular physically, mentally and/or emotionally.

Elizabeth: When you prescribe, how do you know what herbs to use?

Anne: The Ayurvedic method is not ‘like cures like’, but rather, we choose compensatory, opposite qualities in the herbs we prescribe. There are lots of ways in which you would choose a plant. First of all, we need to know how it works with the doshas. Also, how it works with what we call the ‘attributes’ – gunas – which in Ayurveda are understood as pairs of opposites: light and dark, heavy and light, etc. If you have a lot of vata, then you are likely to be light because you are mainly made of ether and air, whereas water and earth are the heavier qualities of physical bodies. So we would say of a vata person that they are light, dry, subtle, mobile, cold.

Plants also have attributes, and so for vata, we would think of using something like shatavari (Asparagus racemosus) which is heavy and dense. It is a sweet root and its effect is grounding and stabilising.

Elizabeth: It is fascinating that one of the ways in which we can determine the qualities of plants is by their taste.

Elizabeth: It is fascinating that one of the ways in which we can determine the qualities of plants is by their taste.

Anne: Yes; if a plant is sweet-tasting, we know that it is likely to be heavy. If it is bitter, we know that it is likely to be light. If it is astringent, it is also light. Another consideration is whether something is warming or cooling. Mildly pungent things such as ginger and cardamom are warming, which is also good for vata, because vata people are cold.

Jane: Can you briefly say something about pitta and kapha?

Anne: Pitta is composed of the elements fire and water. It governs transformation – for instance, the process of digestion – and the function of enzymes and hormones in the body. When we eat, our food is broken down by enzymes or the digestive ‘fire’ into tiny molecules so that it can be absorbed by the gut and pass into the bloodstream. Similarly, when we are talking and the sound of the voice is carried through the ether and enters our ears, we need our powers of mental digestion given by pitta to transform it into useful knowledge. If there is not enough, it just goes straight out; as we have just said, it is the nature of vata to move things along.

So the pitta allows things to be digested at all levels. Pitta tends to be hot, and if it goes out of balance, it causes symptoms such as inflammation or indigestion. So cooling herbs such as aloe vera or chamomile tea will help to balance it.

Kapha is composed of water and earth, and it is the dosha which governs the physicality of our bodies. It provides structure and stability, the framework, to house pitta and vata. So kapha people are good at physical things like gardening and working with the earth; they are supportive and nurturing – earth mothers. But when out of balance, they can become lethargic and heavy in mind and body. Pungent herbs like ginger, cinnamon, cardamom and cumin will help to stimulate and energise them as well as clear congestion.

Anne’s garden viewed from the house. Photograph courtesy of Anne McIntyre

Western Herbs

Elizabeth: Whilst talking to you, we have a view of your beautiful garden in which you grow all sorts of different herbs and flowers. I know that you use many of these in your work, not just herbs brought from India where Ayurveda has traditionally been practiced.

Anne: Yes, I have been very interested in the qualities of Western plants. In my book Dispensing with Tradition, [4] I have classified many of them according to Ayurvedic principles: whether they are light or heavy, heating and cooling, what their taste is, etc. A lot of these herbs had not previously been categorised like this, because they were not known to traditional Ayurvedic doctors.

Jane: Do you think that there is any advantage in taking medicines based on plants which are local to you?

Anne: The main reason I started working with Western herbs is that it seems unnecessary and perhaps unwise to be bringing herbs all the way from India when we have our own here. As long as we understand Ayurvedic principles, and we understand the patients according to the same principles, then we can use any appropriate herbs.

Elizabeth: You also have more control over the quality of the herbs; you can know how they are grown, for instance.

Anne: Exactly. I actually find it hard to trust herbs when I don’t know their source. I grow a lot of the herbs I use myself, or else I obtain them from people that I know. If you order herbs from India, you have no idea how they are produced and how they are treated after harvesting. India and China are probably the most polluted countries in the world; the air and water supplies are contaminated, and this will inevitably have an effect upon the plants.

Aloe Vera Plantation, Fuertaventura, Canary Islands, Spain. Aloe Vera is a cooling, bitter plant which decreases pitta. Photograph: Nikodem Nijaki via Wikimedia Commons

The Life Force of Plants

.

Jane: My understanding is that the purity of the herbs is especially important in Ayurveda, because it is not just a matter of the properties of the plant, but there is also the prana – its living energy – which is transmitted to the patient.

Anne: This is not just in Ayurveda; it is also discussed in Western herbalism as ‘the life force’ of the plant, which is just a different way of talking about prana. All herbal traditions have a similar concept.

Elizabeth: So the big distinction here is not between different herbal traditions, but between the Western system of pharmaceuticals, where the thing that is considered important about a plant is the ‘active ingredient’.

Anne: Yes, the pharmaceutical companies make a plant into a stronger medicine by leaving out what they see as secondary components. But actually, it is these secondary components which help to augment or buffer the effects of the active constituents, helping to make the remedy more effective and prevent side effects.

One of the things we have to be mindful about these days is the effect of the mass production of herbs. In commercial enterprises, herbs are handled numerous times; they are harvested, then dried, then put into packaging in factories before being transported half-way across the world in containers. At every stage of this process prana is lost and by the time they appear on the shelf of a health food shop, there may be little left.

This is why I could not imagine being a herbalist without a garden. It is really important to me that I can grow, pick and prepare my own remedies, as well as forage herbs from the wild.

Jane: What kind of things help to preserve prana?

Anne: We try to handle the plants as little as possible, and also to reduce the time between harvesting and their conversion into medicine, such as tinctures or teas. The same principles apply, of course, to the plants we eat; the less handling and the more quickly they reach the table after picking, the more nourishing they are.

You can look at the whole healing process in terms of prana. All plants have their own particular pranic energy, and we determine what this is by looking at its attributes – heaviness, lightness, etc. as we have already discussed. And each of us, also, has our own pranic energy which can be in harmony or out of balance.

One interesting phenomenon is that because of this correspondence between energies, people can often home in on a plant that they need by themselves. When I teach groups about herbs, I sometimes send people out to find a plant which corresponds to their own doshic imbalance, to find a herb they feel resonates with them, and then to just use their five senses to discern what its qualities are, and to write something down.

Jane: And do they get it right?

Anne: Just about always. And I find this interesting, because we tend to think that people in previous times had a wisdom about nature which we have now lost. But actually, half an hour of contemplation can tell you so much about a plant and its healing potential. The plant is giving out the information and we just need to zone in.

Gokshura (tribulus terrestris) growing on a beach in the Philippines. The fruit of this small plant is heavy and oily; it decreases vata and pitta and is widely used as a rasayana (rejuvenating) herb. Photograph: Obsidian Soul via Wikimedia Commons

Preventative Medicine

.

Elizabeth: Another thing that distinguishes Ayurveda from allopathic medicine is the extent to which it is preventative.

Anne: Yes; as I have explained, what we look for in Ayurveda is the underlying state – the balance of the doshas. Most people in the West wait until they have symptoms before they seek help, but in Ayurveda there is the notion that there are six stages to disease, and the first three happen before any problems are frankly visible. If we can return ourselves to balance at this stage before the symptoms develop into something more serious, we have a good basis for preventative medicine.

Therefore the Ayurvedic system teaches us to recognise imbalances at an early stage. It also teaches us how to develop a healthy routine for daily life – our dinacharya – which is one of the mainstays of preventative health.

Jane: So it is not just a question of taking a medicine, but thinking about our whole way of life?

Anne: Yes, because we have to ask: what is affecting the dosha? They say that there are three main causes of disease. Firstly, there is ignorance; we don’t know how to look after ourselves or understand our own constitution. Secondly, we may have inappropriate attachments of the senses – meaning that we feel that we need things that are actually bad for us, like a glass of whisky when we get home from work. And thirdly, there are what we might call ‘crimes against wisdom’ – meaning that we know very well what is good for us, but we choose to ignore it.

These three things govern the choices we make about our lifestyle, and they in turn, combined with everything that happens to us – what we are putting out in our daily lives and what is coming in – influence our doshic balance. And this affects us in profound ways, because the doshas influence our physical state, our emotional state, our mental state, and our whole interaction with the cosmos around us. In that sense, Ayurveda is a truly holistic medicine – because we need to attend to all those things in order to cure a problem.

Herbs are amazing because they resonate on all these different levels; mental, emotional, physical, and also at a spiritual level. In my own practice, I feel that the more I can engage with them at an energetic level, the better I am as a practitioner. But in order to learn more about these more subtle dimensions, I need to be less busy and have time to just be with the plants in a contemplative kind of way.

Jane: Can you give us some idea of how a herb might resonate at a spiritual level?

Anne: Take rose or gotu kola for example. They are sattvic herbs – meaning that they have the quality of goodness, positivity, truth, serenity and balance – with a spiritual energy that has the ability to connect us to our higher selves and to a place of love… Rose has always been ‘the love herb’!

Anne: Take rose or gotu kola for example. They are sattvic herbs – meaning that they have the quality of goodness, positivity, truth, serenity and balance – with a spiritual energy that has the ability to connect us to our higher selves and to a place of love… Rose has always been ‘the love herb’!

Jane: There is also a lot of wisdom in Ayurveda about how to deal with old age, which seems very relevant to our situation today in many Western countries, where we are concerned about our aging population.

Anne: Yes; there are eight branches of Ayurvedic medicine, and one of them is called rasayana which is the science of rejuvenation. The ultimate aim of Ayurveda is to attain moksha – enlightenment and bliss – but we need as long as possible in this lifetime to do this (even though I originally thought I could attain it by the age of 30)!

There are certain herbs, such as guduchi, gotu kola, gokshura, ashwagandha and shatavari, which are very helpful for old age. When you are post-menopausal – and this is the same whether you are a man or woman – then you are basically in the vata stage of life, and you need things which will strengthen your vata so that you remain youthful in both mind and body. Vata is also to do with connection to subtle realms.

Herbs and flowers in an English garden – sage, rosemary, basil, chives, chervil and lavender – all of which have medicinal as well as culinary uses. Photograph: Peter D Anderson/Alamy Stock Photo

Global Dimensions

.

Elizabeth: Can you say more about the relationship between plants and human beings? Many people are very passionate about plants, and when they are working with them they feel as if they are in contact with intelligent, living beings.

Anne: It does not surprise me that we have strong relationships with plants, because after all, they are fellow beings in the world, and before we put ourselves into high-rise flats and enormous cities, we lived in very close contact with nature. In fact, everything that sustains human life, including our nourishment, comes from the plant world – even if we eat animals, they depend on the plants they eat. We have a connection with plants that is ancient and forever. We are part of nature and need to recognise this.

Elizabeth: How do you think the knowledge of plants which is embodied in the herbal traditions can be of help to us now, as we think about the changes that will come about from global warming?

Anne: Well, one thing that is clear to me is that the way drugs are used and manufactured in Western allopathic medicine is not sustainable. The production of pharmaceuticals is an industry like any other, and it uses a lot of energy and depends upon long-distance transport. It may not be sustainable for our health either, as it is clear that taking drugs long-term can cause side effects.

So I think it is important that we learn to grow our own herbs and vegetables. It is not possible for everyone in the world to be completely self-sufficient – the winter here in the UK, for instance, is very challenging for growers; it is not like having a permaculture garden in Costa Rica! But the more we can grow ourselves, the better. There may come a point when we will have to dig up our lawns to plant herbs and veg because we really need to minimise the amount of food we are transporting. I was on a train journey in Italy recently and noticed that very few of the back gardens there have any grass; they are all dedicated to growing things like tomatoes and artichokes.

It is not just a matter of climate change. I think for people here – and actually in many other countries – relying upon the state health service is not sustainable because there is too much pressure on it. We need to be more self-reliant.

Jane: As well as being a practitioner of herbalism, you are also doing a lot of teaching, presumably with the aim of educating people to be more self-sufficient?

Anne: Yes, I do a number of courses in which I show people what they can do for themselves. I teach them how to integrate Ayurvedic principles into our lives so that we can have a firm basis in preventative health, as well as an array of tools to heal us when we go out of balance. I teach from home, using the herbs in the garden, and I also have an online course in Ayurveda.

Anne: Yes, I do a number of courses in which I show people what they can do for themselves. I teach them how to integrate Ayurvedic principles into our lives so that we can have a firm basis in preventative health, as well as an array of tools to heal us when we go out of balance. I teach from home, using the herbs in the garden, and I also have an online course in Ayurveda.

I also take groups out foraging in the different seasons – spring, summer, autumn and winter – and learn what wild herbs are out there and how to use them. For instance, there are so many people taking medicines for high blood pressure, and yet you could hardly have more hawthorn – the best herbal remedy for it – in this country. It is literally everywhere and yet hardly anybody knows about it. It seems extraordinary that you don’t see people out picking the flowers and leaves in season – but we have forgotten how useful our native plants can be.

Jane: But do you not think that people are generally much more aware of the value of herbs these days? We all have cupboards full of teas like chamomile and peppermint.

Anne: Yes, very much so. When I first studied herbal medicine in 1977, nobody had heard of it but these days everything is about herbs; we have aromatherapy and, as you say, herbal teas, and even – I think it was in America I came across this – calendula-scented loo paper! Herbs have become trendy, even though people may not know very much about what they do.

One of the problems of herbs becoming fashionable, of course, is that real knowledge can become diluted and there are people giving advice or claiming to be herbalists who are not well qualified. Unfortunately, in the UK, there have been many attacks in the last decade or so on alternative medicine. These succeeded in discrediting homeopathy to the extent that it has never recovered. They have also had a go at herbal medicine: at one point, there were several degree courses at UK universities on herbal medicine, and two doing degrees in Ayurvedic medicine. But one by one their funding has been withdrawn, so now only a few remain.

Elizabeth: By contrast, there is better news for Ayurvedic herbal medicine from Europe. For instance, I have just heard about a new professional qualification [/] as an Ayurvedic naturopathic practitioner in Switzerland, certified with a Federal Diploma, which allows the Ayurvedic doctor full integration into their state-run national health system.

Anne: Let’s hope that something like this can act as a model of how we can establish different ways of doing medicine in all countries.

For more information

on Anne’s work, and for workshops and courses, see

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Wild rose growing in the English countryside. Roses are sattvic plants which promote the quality of love, light, harmony, goodness and virtue. “Sattva enables spiritual awakening and developments of the soul” (see McIntyre, The Ayurvedic Bible, p. 84). Photograph: Alan Barnes / LGPL / Alamy Stock Photo.

First Inset: Anne McIntyre. Photograph courtesy of Anne McIntyre.

Second Inset: Red Ginger Flower (alpinia purpurata) at Palappuzha, Kerala. Ginger root is pungent and warming; it decreases vata and kapha and increases pitta. Photograph: Vinayaraj via Wikimedia Commons.

Third Inset: Gotu Kola or Indian Pennywort (centella asiatica) is used both as a culinary vegetable and herb. It is light and dry, and is an important medicine for enhancing memory and concentration. It therefore protects against the aging process and is used to treat conditions such as Alzheimers and ADHD. Photograph: Forest and Kim Starr via Wikimedia Commons.

Fourth Inset: Hawthorn (crataegus laevigata) spring blossom, colloquially known as ‘May blossom’, is an excellent heart and circulatory tonic for high vata and those in the vata stage of life. Photograph: Andrew Dunn via Wikimedia Commons.

Final Image: Herbs and flowers in Anne’s garden. Photograph courtesy of Anne McIntyre.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] LIN YUTANG: The Wisdom of India Hardcover (Michael Joseph, 1949; Reprint edition, Jaico Publishing House, 2005)

[2] JOHN SEYMOUR: The Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency (Dorling-Kindersley, 1997)]

[3] RICHARD MABEY: Food for Free (Harper Collins, London, 2012)

[4] ANNE MCINTYRE & MICHELLE BOUDIN: Dispensing with Tradition: A practitioner’s guide to using Indian and Western herbs the Ayurvedic way (Self published, 2012)

Books by Anne McIntyre

The Ayurveda Bible: The definitive guide to Ayurvedic healing (Firefly Books, 2012)

The Complete Herbal Tutor: A structured course to achieve professional expertise (London, Gaia Books, 2010)

Drugs in Pots (London, Gaia Books, 2011)

The Complete Woman’s Herbal (London, Gaia Books, 1999)

The Complete Floral Healer (Sterling, 2002)

Healing Drinks (London, Gaia Books, 2005)

The Herbal Treatment of Children: Western and Ayurvedic Perspectives (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2005)

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments