Well-Being & Ecology _|_ Issue 23, 2023

An Integral Approach to Dementia

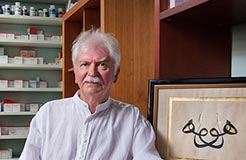

Gerontologist Bettina Wichers talks about her holistic understanding of this widespread disease of old age

An Integral Approach to Dementia

Gerontologist Bettina Wichers talks about her holistic understanding of this widespread disease of old age

Bettina Wichers is an independent gerontologist and lecturer at the University of Göttingen who has specialised in the understanding dementia. She has worked for more than 25 years with nurses and care-givers in nursing homes, and has developed a unique framework, based upon the Integral Theory of the American philosopher and writer on transpersonal psychology, Ken Wilber, which aims to brings all the issues surrounding dementia – medical, psychological, social, spiritual – into a coherent framework. She is currently engaged in writing a book which expresses her evolving understanding of dementia from a unitive perspective. She talked to Richard Gault and Jane Clark via Zoom from her home in Germany.

Dementia is surely a matter of concern to everyone. Even if we ourselves do not come to suffer from it, there is a reasonable chance that we will be intimately connected with somebody who does, and may even become carers for them. And it is of course also a huge social issue in the contemporary world. It is estimated that currently about 55 million people globally suffer from the condition, including eight million in Europe and seven million in the USA. In most economically advanced countries, it is expected that the numbers will grow over the coming decades because of the demographics of an ageing population.

Dementia is surely a matter of concern to everyone. Even if we ourselves do not come to suffer from it, there is a reasonable chance that we will be intimately connected with somebody who does, and may even become carers for them. And it is of course also a huge social issue in the contemporary world. It is estimated that currently about 55 million people globally suffer from the condition, including eight million in Europe and seven million in the USA. In most economically advanced countries, it is expected that the numbers will grow over the coming decades because of the demographics of an ageing population.

Bettina’s interest in the subject of dementia was sparked by her early work experience. She originally studied educational science, which in Germany is a university-level subject, and one of her first jobs was in a school for nurses teaching the care of the elderly. But she very soon recognised that she had no real idea about how to deal with people in nursing homes; the books available at the time mostly taught psychology and sociology as they apply to healthy older people. This prompted her to look more deeply into dementia, and her research quickly convinced her that she was not the only person who did not understand the condition; it seemed that most people didn’t either. So 14 years ago, she went back to university, this time to the University of Erlangen, and took a master’s degree in gerontology, specialising in dementia.

By this time she had been aware of Integral Theory for several years, and her master’s thesis was titled ‘A Blueprint for an Integral Concept of Dementia’.[1] She explains: “Much of my working life since then has been devoted to working with nurses and dementia patients using the theory as a framework. Then about four years ago, something happened in me – you could call it a shift in consciousness – which changed my perspective again. And it is this which I am now working to express by writing a book. So my own understanding of dementia is evolving, and it is important for me to say this as a starting point.”

Elderly Japanese Ryukyuan women playing gateball, a Japanese version of croquet, Kurima Island, Okinawa, Japan – one of the five ‘blue zones’ of healthy old age. Photograph: philipjbigg [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

The Physiological Nature of Dementia

.

Bettina agrees that the prevailing understanding of dementia is first and foremost what most people think it is: a disease of the brain. That is how the World Health Organization, in the ICD 10/ICD 11 which define the main diseases of the world, categorises it; and likewise the DSM 5 – the manual of the American Psychiatric Association – which is also very influential in specifying diseases in the psychiatric field. We are currently in the process of changing over from ICD 10 to ICD 11, and this has meant slight changes to the diagnostic criteria. For example, there is now some reluctance to use the term ‘dementia’ at all, as the American Psychiatric Association has removed the word from its manual and replaced it with ‘neurocognitive disorders’.

What everyone wants to know, of course, is whether the condition is preventable. The most frequent question Bettina is asked is: how can I stop this happening to me? Her reply is that, whilst there can be no guarantees, there is no doubt that dementia is to some degree a lifestyle disease. “There are people, scientists, who say: if you get old enough, you are bound to get dementia. I don’t go along with this, because I think there can be a degree of resilience against the disease, and we have to find out how to develop this. Not every old person gets dementia.”

So what helps us to become more resilient? “Well, there are many things that we do in our modern society that are not helpful: we don’t move or exercise enough; we eat processed foods, we eat too much; we drink too much alcohol and so on. We’re letting a lot of toxins into our body and we don’t do enough to ensure that they go out again. One very significant thing is sleep: we don’t sleep enough and particularly we don’t get enough deep sleep, which is what seems to be important for the body.” (For a recent ‘long read’ in The Guardian newspaper on what we can do to prevent dementia, click here [/])

To support her view, she points out that there are other cultures, other places, where things are different. For instance, there are, what have come to be known as, ‘blue zones’ [/], which are five places around the world where people age very well. “When we think about old people, we assume that means that they are necessarily unhealthy. But on the Japanese island of Okinawa, the people live to be both very old and very healthy. Before they were exposed to Western culture, it was not uncommon to live to be 100 or 110. Although they are very slow – they don’t have much power any longer – people are still able to look after themselves. They help each other – they have a very developed network of social contacts called moai – and every day they go to the sea and gather their seaweed, and suchlike. They have a meaningful day and meaningful work, and their minds are active.”

The main point that Bettina wants to emphasise is that dementia is a complex condition: “There are a lot of things we don’t understand about it. People mostly just look at the body, at the level of matter. This has been a problem because pharmaceutical research has spent vast amounts of money trying to find drugs which can reverse its effects with very little success because they have tried to find a single cause for it. They wasted thirty years focussing on finding a way to dissolve the plaque in the brain, when it was already known from research that this was not the single, isolated problem.”

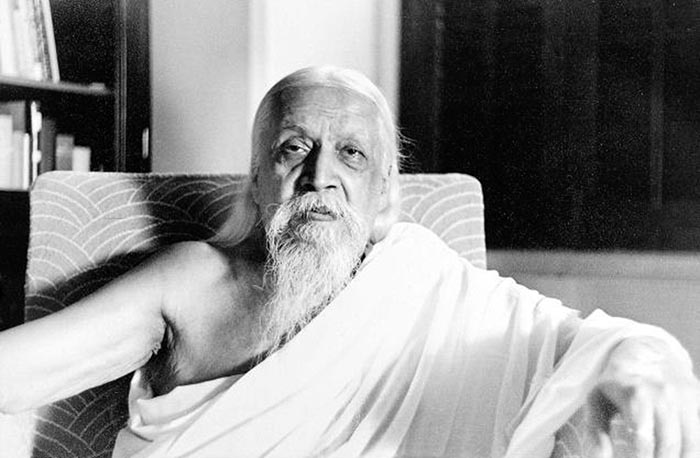

Ken Wilber, the founder of Integral Theory. Photograph: You Tube [/]

An Integral Approach

.

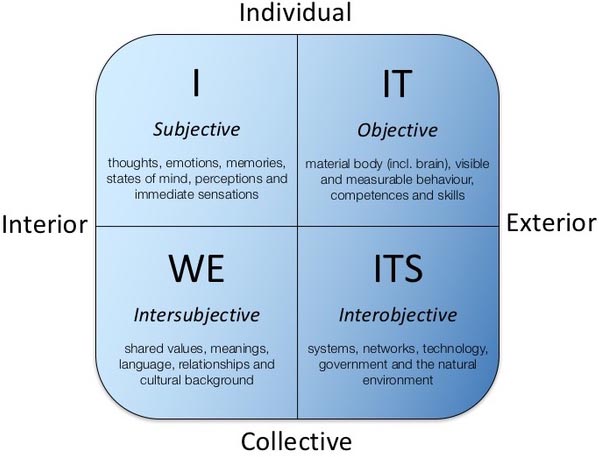

The integral approach was developed by Ken Wilber in the early 1970s. It is fundamentally a meta-theory (that is, a theory about theories) which aims to bring a whole range of ideas drawn from many different areas – western psychology, eastern philosophy, neuroscience, sociology, etc. – into a single comprehensive vision. The ‘All Quadrants All Levels’ (AQAL) model, shown below, aims to provide an easy-to-view schema within which every form of knowledge and experience about a given phenomenon is put together on a simple grid. This is divided into four quadrants expressing two dichotomies: inner/outer and personal/collective.

Horizontally, the diagram expresses the idea that there is always an inner and an outer aspect to things. At an individual level, there is something happening objectively to the person which we can see and measure, but there is also something going on in their interior – their intimate subjective experience. Vertically, it embodies the idea that there is also a collective or interpersonal aspect: there are implications at the level of community both objectively in terms of physical manifestations and subjectively in terms of relationships. The four quadrants are labelled according to the corresponding pronoun – I/it and We/its.

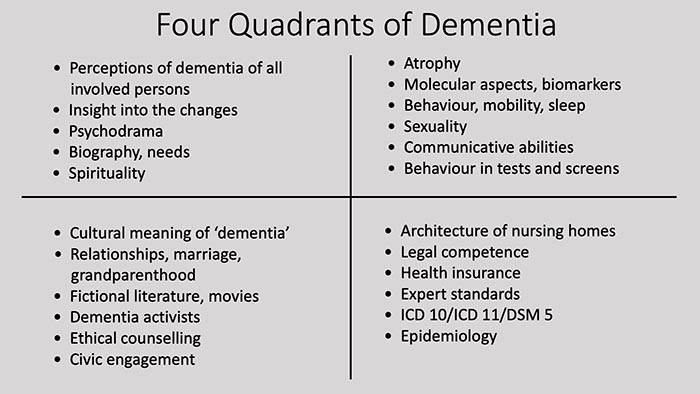

Bettina’s particular contribution has been to map the phenomenon of dementia onto this kind of grid. She explains that the goal at first was to just display the complexity of the situation, not to present any kind of a solution. “I meant it merely as an aid for helping us understand that the condition has many dimensions and manifestations. What I came up with is a diagram (see below). You can see that all that we have been talking about so far – the biomedical research and all the information we have about what is happening in the synapses, etc. – is just one aspect, the upper right, individual objective ‘IT’ quadrant. As a society, we tend to focus on this, and we don’t look enough at the interior aspect, which is what I have put into the top left quadrant – the ‘I’ quadrant; this is how dementia is subjectively experienced.”

When we look at the bottom quadrants which express the social level, we see the same pattern. “We always look on the outside, how can we build nursing homes and so on, or what do can we do with law and the health system. But we tend to pay less attention to the communities of families and marriages which are the human contexts where dementia has a presence and often a very great effect.”

Bettina’s own mapping of dementia onto the AQAL grid

The Integral Model in Action

However, although she did not set out to find solutions, in the end Bettina found the integral model extremely helpful when she returned to her position within the care system. “I always kept it in mind whilst I was working, and it provided me with a way of navigating many different situations that arose. For instance, there could be problems with the relatives of a patient – say, a daughter might be very upset about her mother who is caring for a father with dementia. This has nothing to do with the father or his condition, but the conflict between daughter and mother may confuse him, causing him to become angry and aggressive. In the end he may even need to be sedated with medication, without any of the parties involved understanding what caused this seemingly sudden anger, and the sedation may lead to other complications such as a fall, and so on. There are so many things going on around dementia that cause disorientation in the whole family – even within the whole of society – and this makes everything much, much worse. If you then have a care service which is not very helpful because it cannot see the complexity of such situations … well…”

Bettina’s main job was training carers who were on the frontline of dementia support, and it was here that she found the most immediate application of the theory – although it took time to work it out. One problem that she quickly came to recognise was that the people she was teaching had very different levels of self-awareness: “There were some who just didn’t ‘get’ the different aspects expressed by these quadrants – who were not able to, for instance, empathise or imagine what was going on inside someone with dementia. So they weren’t able to understand what effect their actions had on them. They would say to a person with dementia: ‘Why haven’t you done this yet? I told you to do it ten minutes ago’. With these carers, Bettina had to develop clear guidelines and sets of instructions about what to do or what not to do, and not think about ways of increasing their overall awareness. “Whereas others were totally aware psychologically, and perhaps even spiritually, and so I had to teach them very differently.”

People also had very different learning styles and levels of education: “If you try to teach a person who is not able to learn through listening by talking a lot, they will never learn. You have to sit with them while they are working with a patient and show them how to do it. Seeing all these aspects at the same time, not just looking at one thing, and working with the complexity of a situation – this is one gift of the integral approach, and for me it worked very, very well.”

Of course, many of the problems Bettina encountered lay outside her immediate control, in the physical and social setting within which dementia care takes place: “In nursing homes in Germany, we often have care-givers who are not very well educated. Many of them are not properly trained in looking after people with dementia. They are employed because we have a problem finding enough assistants; they can arrive in the morning and immediately be assigned to washing a patient when they know nothing at all about the condition.”

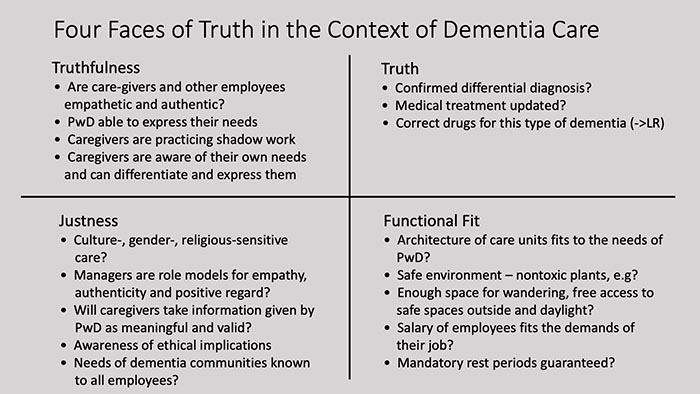

Care workers are also poorly paid and work very long hours, often in buildings which are architecturally unsuitable for the care of dementia patients and within a financially stretched social care system, etc. This has prompted Bettina to develop another AQAL model, based on a Wilberian model of the validity claims of Jürgen Habermas [/]. Drawing upon her many years of experience, it expresses some of the factors which would have to be in place for dementia care to be provided more appropriately. She refers to this as ‘The Four Faces of Truth in the Context of Dementia Care’.

Bettina’s mapping of factors relating to the care of people with dementia (PwD)

A Different Perspective on Dementia

.

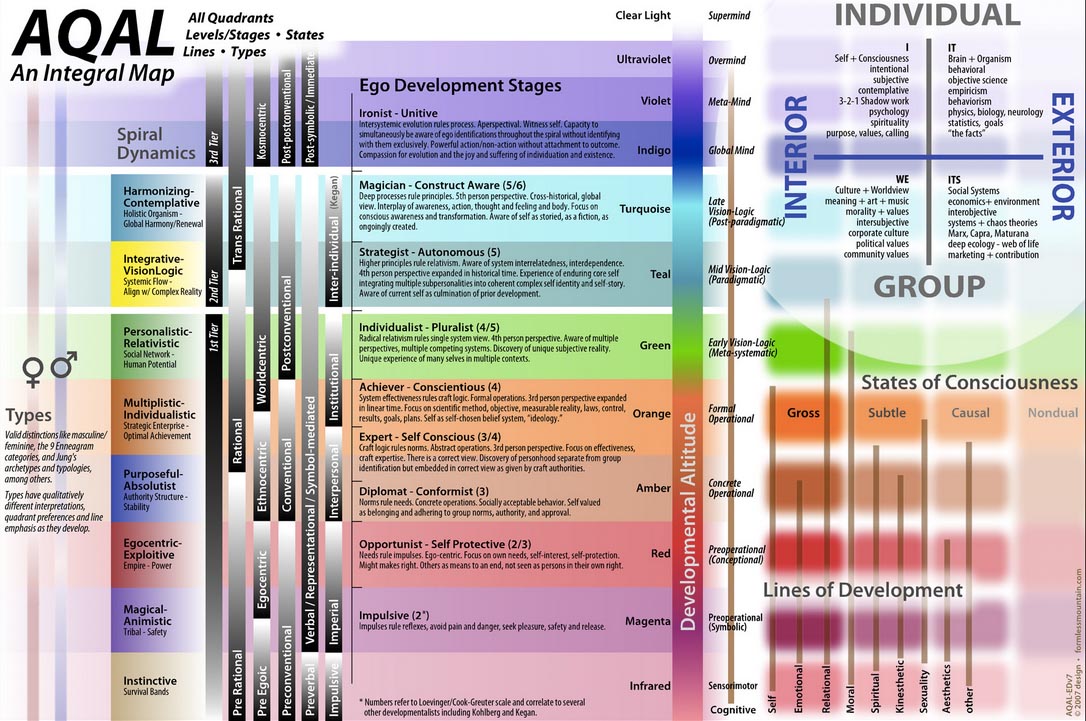

One of the most interesting aspects of Integral Theory is that it includes a model of adult development that incorporates the idea of spirituality. Specifically, Wilber turned to the schema developed by the Indian philosopher and mystic Sri Aurobindo [/] (1872–1950) who in the early twentieth century developed a system called Integral Yoga which aimed to delineate the possible evolution of the human being into a divine life in a divine body. He delineated a number of stages, from the ordinary state of physical awareness to that of what he called ‘overmind’ or ‘supermind’ where there is awareness of the one, cosmic reality.

These ideas have been brought into conjunction with western psychological understanding to create the master model of Integral Theory, as shown in the ‘integral map’ of the AQAL perspective below. Sri Aurobindo’s stages are shown on the right-hand side, but the part of the schema which is more familiar in the Integral field is the central panel, which describes seven main stages of development, from the instinctual to what Wilber has termed the ‘Ironist–Unitive’ level. Bettina works with both stage models, depending on the context.

Comprehensive AQAL Chart by Steve Self, showing both the levels of consciousness developed by Sri Aurobindo (centre right) and those delineated by Wilber (centre). Diagram: The Ken Wilber Gratitude Fund [/].

Move your computer mouse over the image in order to enlarge

So, in what way does awareness of this evolutionary or developmental process help us to understand dementia? Well, one thing, Bettina explains, is that the condition can look very different depending on which perspective we adopt. If we look at it from the degree of, say, the ‘Achiever’, it is a complete disaster. For someone in this state, the main priority is to be successful in the world, so the focus is on planning and setting goals, and developing ways of objectively measuring things – all of which are seriously disrupted by dementia. However, at the ‘Individualist–Pluralist’ level, there is the emergence of humanistic awareness and the recognition that there are many ways of doing things. “From this perspective we understand that there is not just one way to be a human being. So, for instance, we don’t feel offended by someone who is different, but instead we can embrace that. We can relate to differences and hold different points of view within ourselves.”

This can really change our attitude towards disability and disease. “We usually see dementia as a really bad thing; we demonise it, really. But from a pluralist perspective, it is just another possibility, and we can even perhaps see that it is of value. Sometimes I think people with dementia are doing a good service for us as a society because they make us develop our capacity for care and understanding. This is something known by a lot of parents who have a sick child; they say, my child did me a service.”

Another thing that the existence of dementia makes clear is that any model of adult development must be able to explain regression as well as evolution and progression. “For people with dementia, it seems that the evolutionary process does not continue, but they start to go backwards. They go more and more into their early adulthood and then into their childhood until in the final stages they are unable to speak.”

But this, again, does not have to be seen as a totally negative process. Bettina goes on to relate an experience that she has had with very late-stage dementia patients. “People at this stage often have two different modes of behaviour. There is one of agitation and disorientation, where they really don’t know where they are or who they are. Then there are other times where they’re just sitting peacefully and are very quiet, very relaxed – no difficulty, no anxiety. I have had the thought when sitting with someone in this state that in some ways it would not be different to be sitting next to a Zen monk in deep meditation. What characterises people with advanced spiritual development is that they have no ‘I’; through practices such as meditation, the ego is dissolved. And this is also the case with people in the stages of dementia when they are in this calm state: there is no ‘I’.

And in fact, there is some recent brain research which confirms that there are significant similarities between the states of people in late dementia and those in meditation. Scans of experienced practitioners whilst they are in a state of deep contemplation show that activity in one of the brain’s networks called the ‘default mode network’ is very much reduced, or almost entirely quiet. “This is the part of the brain which constantly tells us stories about ourselves, and during deep meditation it is very different from how we usually are; normally, the default mode network is active all the time. And it is the same with people in late-stage dementia: the precuneus – which is an anatomical and functional part of the default mode network, and is the part of the brain where the ‘I’ perspective resides – physically degenerates, which may explain ego-dissolution in the context of dementia.”

A Unitive Understanding of Dementia

.

Experiences such as this have convinced Bettina that the best way to understand dementia is from the unitive or what she also calls ‘the involutionary perspective’. “There is the One – the One Reality, I refer to it usually as The Absolute – and all existence arises from this. It is arising at every moment out of nothingness. Then there arise – in Sri Aurobindo’s scheme – the levels of spirit, mind, life and finally, matter. We usually look at things the other way round, which is what is called in integral theory the way of evolution; we start with matter and progress to life, mind, spirit and finally, if we can go so far, non-duality. But actually, our existence infolds from the One.”

In other words, our normal view of spiritual progress is inverted; rather than seeing it as proceeding from a lower state to a higher one we see – or even, perhaps, experience – ourselves as arising in a top-down process of emanation from the One Reality. This is very much the view of all the great mystical traditions – perhaps most directly, the Neo-Platonist tradition. From this point of view, as Bettina goes on to explain, as we become more spiritually aware, then the question becomes not “…how do I evolve?” but rather: “what wants to involve in me? “The Absolute wants to make experiences through me, so what is it that I am meant to be in particular? Each person has something that wants to involve specifically through them. From this unitive point of view, consciousness consists in not forgetting who we really are. So one way of understanding dementia, perhaps, is that if we consistently refuse to remember this throughout our life, then it could have an effect upon our brain.”

For Bettina, dementia is a paradoxical condition because the mind progressively stops working, but it continues to maintain the body for quite a while. “It can’t let go of this body. And this is something that Buddhists often talk about: our great attachment to matter, to the material world. But even though the mind dissolves itself, it is still in consciousness, because this existence is always in consciousness; it never falls out of consciousness. So even with quite advanced dementia sufferers, there are still some lucid moments when consciousness kind of shines through.”

This would seem to be confirmed by a mysterious phenomenon called paradoxical lucidity.[2] This is when, in the very, very late stages of advanced dementia, a patient who has previously lost the ability to speak and communicate sensibly, suddenly starts speaking again. It is as if for some moments, sometimes up to an hour, they are restored. This always happens very close to the terminal stage, mostly within about seven days of death, and it cannot be explained physiologically, that is, in terms of top right quadrant thinking. From that point of view, the brain has degenerated, and it cannot suddenly regenerate for a few minutes.

So how does Bettina understand what is happening here? “I think that again we can only understand this by going into the transpersonal or spiritual realms. For me, this paradoxical lucidity is an opening into what is behind this existence; an indication that there is another realm beyond this physical world which is always there, for everybody. We can always remember that other realm, even though we don’t always know how to – which is the reason for spiritual practices. So, paradoxical lucidity is a reopening of the story which was infolded through this person, and a remembering of what this particular life was originally thought to be for.”

Would she say, then, that this is another way in which the occurrence of dementia can teach us something valuable about ourselves? – that the original person is never lost? Our material body seems to degenerate, but what we really are remains intact. Bettina agrees, but with caution: “Yes, but I think we have to be careful how we put it. It is not this body or anything physical that remains intact, but rather it is the idea of us – the spirit, the creational spirit of us – which wishes to be infolded in our body and in our life: that is what remains.”

At this point, we have to finish this fascinating conversation, and thank Bettina for giving us a host of new insights into this challenging condition. We very much look forward to reading her book when it eventually comes out.

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Residents in the ‘dementia village’ at Hogeweyk in the Netherlands. This pioneering project, which opened in 2009, has been designed to give dementia patients as much freedom and agency as possible. The model is now being adopted throughout the world. Photograph: from Hogaweyk.

Inset: Bettina Wichers. Photograph: by herself.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] This is available only in German. For a digital copy, click here [/].

[2] MASHOUR A.M., Frank, L., ‘Paradoxical lucidity: A potential paradigm shift for the neurobiology and treatment of severe dementias’ in Alzheimer’s & Dementia, Vol. 15, 2019, pp. 1107–1114.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Consciousness as the Ground of Being

Physicist Federico Faggin talks about his new theory which puts our inner experience and the desire to know ourselves at the centre of reality

Memory, Habits and Wholeness

Biologist Rupert Sheldrake challenges the dogmas of conventional science, and explains how recent research supports his alternative theory of morphic resonance

Richard Holding: The Art of Acute Listening

The distinguished osteopath talks about his holistic approach to healing

Mindfulness Meditation – Alleviation of Suffering for Neurological Conditions

Niels Detert, Consultant Neuropsychologist, explains how meditation can help people with long-term medical problems

READERS’ COMMENTS

What an encouraging and positive view of something which I suspect many of us are very frightened and confused about. I was particularly intrigued by Bettina’s reference to the precuneus – I had no idea the ego has a physical correlate in the brain!

Since speaking with Bettina I came across this:

Greek mountain tea used to treat Alzheimer’s

German research on Greek mountain tea, also known as verbena and Tsai TouVounou, has emphatically shown that it can prevent or even reverse Alzheimer’s disease, a degenerative and debilitating mental illness that now affects many elderly people around the world.

Two years earlier, a study by the well-known Alzheimer’s researcher Professor Jens Pahnke – the so-called Alzheimer’s hunter – had shown in mice that daily treatment with a sideritis extract dissolves and improves the animals’ memory performance.

The already onset of nerve cell death in the mice could also be stopped thanks to mountain tea. Neurology Professor Jens Pahnke from Ottovon Guericke University Magdeburg in Germany said of his research: “By drinking mountain tea for six months, Alzheimer’s patients have the disease to the level of nine months ago reduced and then stabilized. “He added,” I had a patient with memory and orientation disorders who could not even go to the bathroom by himself and now, after giving him mountain herbal tea for two months, he plans to go with a friend to travel to the Alps. ”

The researchers working with Pahnke are therefore of the opinion that sideritis extract is an effective and very well tolerated measure in Alzheimer’s disease. (source https://www.greekflavours.com/en/blog/greek-mountain-tea).

The tea has other benefits – so time for a cuppa!

Where can you buy Greek Moutain tea?

There is growing evidence for the role of the precuneus, which I consider an important factor in my understanding of dementia, although I still look at it somewhat differently, from the perspective of involution: here are some recent findings that support my views – but from an evolutionary perspective, from matter to mind. https://neurosciencenews.com/self-awareness-brain-23515/

Sending prayers and support. My mother who had been diagnosed with Dementia for 3 years at the age of 82 had all her symptoms reversed with Ayurveda medicine from natural herbs centre after undergoing their Dementia Ayurvedic protocol, she’s now able to comprehend what is seen. God Bless all Dementia disease Caregivers. Stay Strong, take small moments throughout the day to thank yourself, to love your self, and pray to whatever faith, star, spiritual force you believe in and ask for strength. I can personally vouch for these remedy but you would probably need to decide what works best for you, visit naturalherbscentre .com