News & Views

St Cuthbert of Farne

Jane Clark talks to Kathy Tiernan about her latest book on the great Northumbrian saint

Detail from “St Cuthbert Praying” by Aidan Hart [/]

In the first issue of Beshara Magazine in 2014, we featured a short story by Kathy Tiernan, entitled “The Red Sail”, based upon an incident in the life of the Northumbrian saint, St Cuthbert. Although he died more than a millennium ago, in 687CE, Cuthbert’s spiritual presence continues to pervade the landscape of North-East England, and his shrine in Durham Cathedral attracts thousands of visitors every year. 20 March – appropriately, St Cuthbert’s day – saw the publication of a full-length novel by Kathy, entitled Cuthbert of Farne, which imaginatively reconstructs his life and times. I talked to Kathy at her home in Berwick-on-Tweed about the writing of the book, and why she feels that St Cuthbert still has relevance for us in the 21st century.

Jane: This is your second novel about Cuthbert; the first, entitled Place of Repose,[1] is about the period after his death, so this one is a kind of prequel, covering his life and giving more background about its religious and political context. What has drawn you to write about him?

Kathy: I was brought up in Northumberland and now live very close to Lindisfarne and the Farne Islands where Cuthbert went into retreat. He is still very much a presence here. So in one sense he was part of my childhood, and of my inner landscape. But there was also a specific incident which occurred a few years ago, in London, when I went to an exhibition at the British Library which featured the Lindisfarne Gospels [/]. This displayed some objects which had been found in St Cuthbert’s coffin – his travelling altar that he used when he was riding through remote villages to evangelise, his personal copy of the St John gospel and his pectoral cross. When I saw these artefacts which he had used and handled, they had a profound effect upon me. This legend, this Father Christmas-like person I had grown up with, suddenly became a real person and I immediately felt that I wanted to write about him.

Jane: Can you tell us a little about his life, and why he is such an important figure?

Kathy: Cuthbert lived in the 7th century CE. He was born in the year when a monk called Aidan came from Iona to evangelise Northumbria, so he grew up in a pagan society that had just been converted to Christianity. He was part of the first generation of Christians in the area; there are several saints who lived in the same period, and it was clearly a special time of great spiritual intensity.

We know that Cuthbert was a warrior in his youth, and that he grew up in an Anglo-Saxon environment in which there was constant fighting between rival kingdoms. But at the age of seventeen he took the decision to enter into the monastery at Melrose, which at that time would have been only three or four years old. He spent the rest of his life as a monk; he became a hermit, living on one of the Farne Islands for about eight years, and then, astonishingly, at the end of his life he became Bishop of Lindisfarne, holding a crucial role which to some extent determined the whole future of the kingdom.

Jane: His physical remains eventually ended up at Durham and his shrine became part of the great Cathedral there. So he is still very much part of our world today; in fact, he is probably the most visited saint in the UK.

Kathy: I think one of the remarkable things about Cuthbert is the persistence of his presence in all sorts of ways. In his lifetime, he was revered as a holy man and a healer – there are several miracles attributed to him. But twelve years after his death, his coffin had to be moved and when they opened it, they found that his remains were uncorrupted – meaning that they had not decayed – which was taken as a sign of saintliness. Then the great 8th century scholar, the Venerable Bede [/] wrote his Life of Cuthbert, which was a medieval best seller and ensured his continuing fame down the centuries; it is still in print today.[2]

All this makes him unique amongst English saints in that we know so much about him, and he has been present in an unbroken way from the 7th century to the present. For instance, the community of St Cuthbert, who were called the “Haliwerfolc” (old English for “holy man folk”), persisted for many centuries in various forms.

Jane: One of the aspects of this persistence is the fact that in many of the places mentioned in your book – Lindisfarne, Bamburgh, Ripon, as well as the Farne Islands which are now preserved as bird sanctuaries – there are physical remains from Cuthbert’s time which can be visited.

Kathy: Yes, the landscape up here is still very pristine – it has not been industrialised – and so we can still see what Cuthbert saw. And as I have said, the landscape is very much imbued with his spirit.

The Farne Islands seen from Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland. Photograph: Mattbuck via Wikimedia Commons

.

Healing the Rift

.

Jane: One of the things I like about the book is that it puts Cuthbert’s life into a context, and shows how much interplay there was between the spiritual aspect of life – the men and women who had devoted themselves to spiritual matters – and the political and religious realms.

Kathy: Cuthbert lived at a time of intense religious and political conflict, and, in particular, there was rivalry between different modes of Christianity. On the one hand there was the Celtic tradition established by Aidan, which had an otherworldly, ascetic, close-to-nature ethos. It was close to the ordinary people, and was very much a bare-foot mission; Aidan and Cuthbert walked everywhere and they lived humbly. On the other, there was the Roman Church which was answerable directly to the Pope; this was in many ways to do with the accumulation of wealth and power.

The Synod of Whitby, which happened during Cuthbert’s lifetime, made a choice away from the original Celtic form of Christianity in favour of the Roman Church. Its representative, Wilfrid, became Bishop of Lindisfarne and the Church took over the governance of all the religious institutions in the region – so much so that it began to rival the power of the state, and this in turn caused conflict politically.

Cuthbert’s reaction to all this was to withdraw and become a solitary hermit on Inner Farne. But paradoxically, it was because of his spiritual integrity that he became the one person everyone could agree on. And so at the moment when the Church was in a crisis of leadership, in about 683 CE, the king himself took a boat and went to beg Cuthbert to return and be the bishop. Then, when he had only been in the role for three months, the king and the cream of Northumbrian nobility were killed in a disastrous battle in Pictland, and Cuthbert was directly involved in the aftermath, which involved searching for an heir acceptable to all factions.

So he became the protector of his people in every sense; spiritually and materially. He spent two years getting everything back into order, and when he felt that the job was done, he went back to Inner Farne and died within three months.

Jane: There is an interesting discussion here about the role of a saintly man or woman within a culture – between retreat as a practice and participation in worldly affairs.

Kathy: The way I try to present Cuthbert’s time as a hermit is that it was not so much a removal from society as an act of witness. When you look at the topography of the Farne Islands, you can see that he was not actually trying to withdraw from the world, because he chose an extremely public place to do it, right opposite the capital of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria at Bamburgh. It is just three miles across the sea to the king’s palace, and every time the king left his court he could see the island and know that Cuthbert was on it.

Jane: So what was he bearing witness to?

Kathy: To essential values of the Christianity which he knew. To his tradition and what he felt Christianity – and a Christian society – should be expressing. And at this time, this was very much to do with identifying with the example of Christ. I think that if you had to sum up Cuthbert in one quality, you would say that he was Christ-like. This is why the miracles are so emphasised by Bede, because it was expected that any holy man who identified with Christ would be able to perform them.

He was also there for his people. Visitors were constantly travelling to the island to ask his advice, so he was not trying to cut himself off from people, but rather to be there for them in a different way – as an intercessor if you like. I think that is very much how saints were seen in this period; they were the ear to God. So if you were in trouble, you would ask Cuthbert to have a word on your behalf. And this is still going on; when people visit Cuthbert’s shrine at Durham, they are often bringing their problems to him.

Jane: Cuthbert may have been Christ-like, but whereas Christ quite specifically did not intervene in the political situation of his time – as he was expected to by both his people and the Roman rulers – Cuthbert did agree to take up a worldly role when he became bishop. And he did not do this in order to fight the corner for Celtic Christianity, to turn back the clock, but to bring about unity after the schism. He was consecrated in the Roman manner, and took up his duties in a Church that never went back to the old ways. His work was reconciliation and healing. And this is an interesting example to contemplate at this point of our political lives in the UK, where we are coming to know a lot about irreconcilable disagreements, but do not seem to have worked out a way of resolving them.

Kathy: Yes, he accepted the decision, and did not try to change things. He worked with what he had and moved on. At one of the recent book signings in Durham, a member of the audience picked up the relevance to this to our immediate situation in the UK, and said to me: “What we need in Brexit is a Cuthbert.”

Jane: Well, we don’t seem to have a living saint to call upon at the moment. But perhaps you could say that what we need is a Cuthbertian spirit; the kind of vision and integrity that he had.

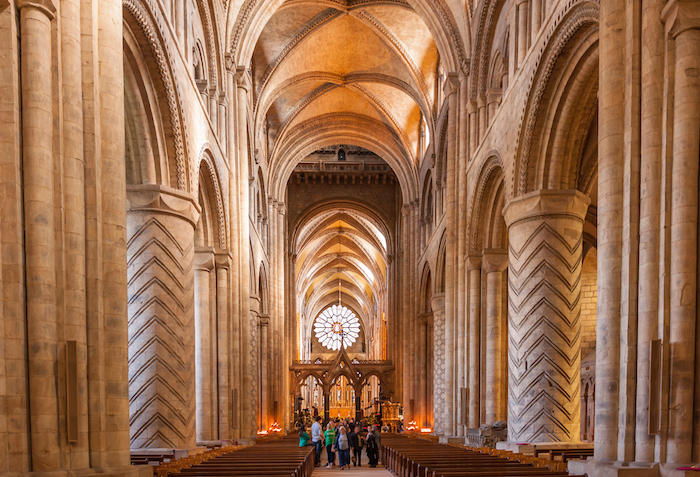

The interior of Durham Cathedral, built in 1093 to incorporate Cuthbert’s shrine. This still lies within the building, behind the high altar. Photograph: T M O Buildings/Alamy Stock Photo

.

The Development of Goodness

.

Jane: Can I ask you about your sources for the book? How interpretive is it?

Kathy: Bede is the main source, of course, but he is not at all interested in questions of psychology or motivation. People in the 21st century are interested in why a seventeen-year-old should decide to become a monk, but Bede is not. Also, he never talks about the religious context; he talks about the way that Cuthbert handled difficult monks, but he never says why they were being difficult. But when you read the history and understand that this was all fall-out from the Synod of Whitby, things make a lot more sense.

I think everyone who writes about Cuthbert writes about their own idea of what a saint should be. I wanted to see what the story looked like to us in the modern day; to explore the process of how a raw seventeen-year-old enters monastic life and ends up being acknowledged as a great saint. This is why I included the character of Aelfled, the abbess who knew Cuthbert from the time she was a young girl through to the very end of his life. She is an outsider who observes him changing and the reader is then left to draw their own conclusions from what she says.

Jane: I think the great achievement of your novel is to portray a truly good person, and the development of that goodness, in an interesting way. There is a saying that the devil has all the best tunes, and in the same way, he has all the best stories. Goodness is too often portrayed as bland and unexciting. Or there is a kind of spiritual sentimentality.

Kathy: I think that the stories about Cuthbert and his life are really interesting and not many people know them. So the aim was to present them in a way which is also dramatically compelling. This was not always easy. Cuthbert was prior of his monastery for more than ten years, for instance, and there is not much that you can say about that time.

Jane: Well, it may have been dramatically uneventful, but the book manages to vividly portray the daily life of the monastery. For instance, there are some lovely passages about Cuthbert’s work as the keeper of the abbey’s guesthouse, in which role he met a very wide range of visitors and travellers. And you remind us that that the monasteries were central to the pastoral care of communities during this period. They were centres of learning and medicine in addition to providing spiritual help and advice to people.

Kathy: Yes, very much so. And this was not only the work of monks; women also had an important role. This is another reason why I wrote about Aelfled the abbess, who was famous for her learning and her healing skills.

Jane: So what next? Is this the end of your literary relationship with Cuthbert?

Kathy: Well, I am rather hoping that these two books turn into a trilogy, with the third one covering the period of the Norman Conquest. This was a time of enormous hardship for the North of England, when once again the forms of Christianity which were established at Durham by the Cuthbert community came under attack. It is a further step in the story of Cuthbert – in the evolution of the Cuthbertian spirit, if you like.

Kathy Tiernan walking St Cuthbert’s Way [/], which runs from Melrose to Lindisfarne

Cuthbert of Farne is published by Sacristy Press and is available from www.sacristy.co.uk

For more on Cuthbert, see:

Kathy’s first book, Place of Repose: A Tale of St Cuthbert’s Last Journey (The Ningaui Press, 2013)

Two previous articles in Beshara Magazine: The Red Sail [/] in Issue 1 and Three Transitions [/] by Richard Twinch in Issue 3.

See also two delightful blogs based on medieval manuscripts illustrating the life of St Cuthbert: A Menagerie of Miracles [/] in the British Library and Make Me an Island [/] at University College, Oxford.

Sources (click to open)

.

[1] KATHARINE TIERNAN: Place of Repose: A Tale of St Cuthbert’s Last Journey, The Ningaui Press, 2013.

[2] VENERABLE BEDE and SIMON WEBB: Bede’s Life of St Cuthbert,

CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2016.

More News & Views

Poems for These Times: 18 – New Year 2024

Benjamin Zepahniah | Faceless

“You have to look beyond the face

to see the person true

Down within my inner space

I am the same as you…”

Introducing… ‘Tiger Work’ by Ben Okri

Barbara Vellacott reads from and discusses a new book of stories, parables and poems about climate change

Book Review: “Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time” by Kapka Kassabova

Charlotte Maberly reviews a book about the search for wholeness, and a heartfelt plea to reclaim our spiritual, physical and emotional unity with nature

Book Review: “Work: A Deep History” by James Suzman

Richard Gault reviews a new book which takes a radical approach to contemporary work culture

Introducing… Bernardo Kastrup and Swami Sarvapriyananda

Charlotte Maberly appreciates a wide-ranging video conversation about Eastern and Western concepts of the self and mind

Connecting Threads on the River Tweed

Charlotte Maberly investigates an innovative project which explores cultural engagement as the driver of ecological change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

0 Comments