News & Views

Cold Fingers

In the midst of a bitter winter, Kathy Tiernan contemplates the history of coal and colonialism in the North of England

Winter ice on the River Tweed, Berwick-upon-Tweed. Image: John Lee [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

All through Boxing Day the east wind roared against the house and lashed the slates with sleety horizontal rain. In my attic office the noise of the wind was relentless, battering the roof, rocking the windows, so that you could be aware of nothing but the wind and the wind’s noise, on and on. I crept downstairs to a quieter room and nursed my post-festive migraine. I didn’t mind too much. We’d had a great Christmas day full of good cheer and excitement; I was ready for life to close down the shutters and say, enough.

Besides, it was freezing cold. Like everyone else in the UK, we’re trying to reduce our fossil fuel use, and to turn on the central heating only if it is unavoidable. Our house in Berwick-upon-Tweed is well-insulated and snugly surrounded by other house walls, so it can withstand cold. But a south-easterly finds it out, finds every crack in the exposed wall and roof, and the house was arctic. I had my thermals on, warm tracksuit, jersey, Arran sweater… and then the fluffy dressing-gown with the hood on over it all to try and keep my head warm. Nevertheless, sitting at the computer, my hands started to get too cold for the keyboard.

It brought back a memory of piano practice long ago, back in my boarding school in the Scottish Borders in the 1950s. The school occupied the eighteenth-century mansion of the Earls of Minto, who had given up on their stately home in the post-war years. It had an exquisite staircase and cupola designed by William Adam and a huge ornate dining-room where plaster cherubs gazed down from the cornices on our dismal breakfasts of black pudding and congealing bacon. No doubt in its glory days an army of housemaids had scurried from room to room with their coal scuttles, stoking up the fires in a score of noble hearths.

But by my time, their ghosts had vanished without trace and the house was cave-cold with that special penetrating dampness of stone houses. Sometimes in the dormitories, housed in once-gracious bedrooms with early Morris wallpapers, then filled with long lines of spring-shattered hospital beds, the water in our toothmugs would freeze on the chest-of-drawers. There were no concessions. Our uniform was a green gymslip that came to just below the knees, where it was joined by a pair of green woollen socks, held up by garters. Beneath were green flannel underpants, a green vest and a pale green blouse. That was it. If it was exceptionally cold a cardigan was allowed. Eighteenth-century architecture became intimately associated in my mind with bone-chilling coldness and emotional desolation.

Minto House, seat of the Earls of Minto from 1703 to 1962. Built in the 18th-century by William Adam, the house was demolished by the 6th earl in 1992 in the face of fierce opposition. Image: www.mintovillage.org

I took piano lessons with a fierce-beaked Scottish lady called Mrs Barclay. For the lessons, we went to an elegant octagonal drawing room with a grand piano, a room heated for Mrs Barclay’s benefit so that her hands were always ready to leap up and down the keys in dazzling glissandos. But for us children the daily grind of piano practice took place in the lower ground floor music rooms, little more than cellars with a glimpse of basement light. Within minutes of starting practice in the winter months, fingers turned white with cold and refused to move – clumsy, ungainly digits hardly able to distinguish a black note from a white. Desperation would set in, between the desire to abandon the sorry charade altogether and the fear of Mrs Barclay’s harangues.

Back in my attic, as my fingers stumbled numbly over the computer keyboard, I wondered, is it time to give up and flick the switch? My husband came into the room holding a thermometer and looking grave. ‘Eleven degrees,’ he said. We had a moment of silent complicity. He turned away and hit the booster button.

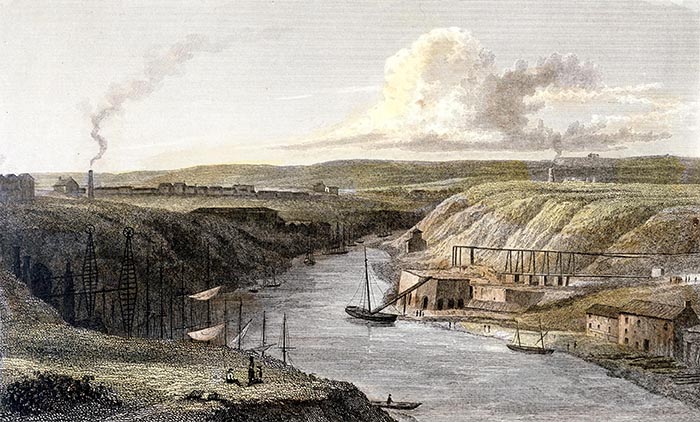

The Wear above Sunderland Iron Bridge, c1829. Both the Tyne and the Wear were important waterways for the export of coal; on the right are warehouses and staithes (platforms for loading), while on the left are the tops of the vessels that will carry it to London and elsewhere. Engraving after William Westall (1781–1850). Image: World History Archive [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

Collieries and Colonies

.

And now, in the slow days of January, the wind has dropped and fog is rolling in over an ebb tide. The house is quiet and only mildly chilly. I am back at the computer with active fingers, ready to slip back on a centuries’ old swell into the imagined world of the novel I am working on. There, a score of colliers are running down the Tyne with top mizzens reefed, the Racehorse [/], is setting off for the North Pole, and a Whitby shipmaster is coming out of the Admiralty offices with a document in his wallet.

Already, here, in this mid-18th-century world, the fossil fuel revolution is well underway. London is swallowing coal in staggering quantities, so that foreign visitors complain that their clothes are soiled by the sooty air in the capital. Much of it comes from Newcastle. Coal from the Tyneside coalfields is shipped down the river by the keel men to be loaded, chaldron by weary chaldron, from the rocking keels into the hold of a Whitby cat. For while Newcastle may have the coals, Whitby builds the ships, the ‘cats’, that carry them. According to contemporary reports, not an oak tree is left standing within a hundred miles of the coast due to the demand for timber. For the sailors and apprentice boys on those ships, life is unimaginably cold and wet; the only solace is the brandy ration. In winter, when sail ropes become too ice-slippery for numbed fingers, there is no choice but to lay the ships up.

There are no routine sailings. Even the most experienced crews can find themselves becalmed for days on end or driven halfway to the Netherlands by a south-westerly squall. The skill of a Whitby master is to get his ship to London in as few days or weeks as the wind allows, to sneak her into dock with the minimum of charges and get the best price going for his owner’s coal. Every extra day at sea means more provisions used, less profit gained.

A beached Whitby ‘cat’ uploading into carts: Painting by Julius Caesar Ibbotson, ca. 1790. Image: National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, via Wikimedia Commons

John Addison, my kinsman in this other world, is thirty-two. Like his Whitby contemporary, James Cook [/], he was apprenticed at twelve years old and has been at sea for twenty years. From nothing, he has worked his way up to become a master on the Whitby colliers and has started buying shares in other ships. It is a slow, hard way to make your fortune – not a fortune even, but a living. John Addison wants more. He wants land, he wants to be a gentleman. A voter. All his hopes rest on the document now in his satchel as he walks away from the Admiralty, heading back to Deptford, heading for home.

And thanks to a 21st- century miracle of technology I can look over his shoulder and read a copy of the document he took back to Whitby, now held in the National Archives at Kew. It is a Letter of Marque, issued after the start of the Seven Years War in 1756 – the war that was to establish England for the first time as a colonial power. It licences him to use his ship, Friends Desire, to attack and capture enemy shipping for his own profit. Captures have to be brought back to London to check that they are indeed enemy ships, but once ‘condemned’ they are legitimate prizes. The profit is divided in a descending ratio between all members of the crew. There were eighty men aboard the Friends’ Desire, eighty would-be privateers, ordinary sailors with no military training of any kind who were ready to risk their lives for fortune with John Addison.

Ship: Friends Desire . Burden: 400 tons. Crew: 80. Owner: John Addison

Commander: John Addison.

Lieutenant: John Broderick.

Gunner: Andrew Harper.

Boatswain: Hezekiel Newmatch.

Carpenter: John Hutchinson.

Surgeon: John Addison.

Cook: Thomas Presswick.

Armament: 10 carriage guns.

Date: 1756 July 31

This was the buccaneering world where empire began, a world of prizes, plunder, trade and colonies, where the open seas could carry men from humble backgrounds to undreamed-of fortune. From enemy shipping to natural resources to other people’s countries, it was all up for grabs. When the buccaneers had made it, the apotheosis of their ambitions was, it seems, to come home and build immortality for themselves in the shape of a country mansion. Land was still the ultimate hallmark of gentility. I think of Minto House and I want to call out to John Addison across the centuries: ‘Don’t do it! It’s not worth it!’

Minto House was built on money from the East India trade; the fourth Earl became viceroy of India. But where did it all end? The boarding school closed down soon after I left and the house became half-derelict. In the 1990s the sixth Earl of Minto, in the teeth of outraged opposition from every conservation lobby in Scotland, went ahead and demolished the entire building [/]. When I returned a few years later to look at the house there was absolutely nothing left. A slope in the ground, some rough grass and the remains of the terraced garden. My green-knickered nine-year old self danced with joy upon the ruins. Perhaps the sixth Earl of Minto did too.

The most famous Whitby ship: the Endeavour on which Captain Cook (1728–1779) sailed to Australia. Built at the boatyard of Thomas Fishburn, it had previously been used in the coal trade. This replica is at the Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney. Photograph: fotofritz16 [/] / iStock

Katherine Tiernan is a writer who lives in Berwick-on-Tweed. She is the author of a trilogy of novels about the great Northumbrian saint, St Cuthbert (see our article). Her next book, ‘Star of the Sea’, a novel based on the eighteenth century history of her family, will be published by Sacristy Press in early summer 2023

More News & Views

Poems for These Times: 18 – New Year 2024

Benjamin Zepahniah | Faceless

“You have to look beyond the face

to see the person true

Down within my inner space

I am the same as you…”

Introducing… ‘Tiger Work’ by Ben Okri

Barbara Vellacott reads from and discusses a new book of stories, parables and poems about climate change

Book Review: “Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time” by Kapka Kassabova

Charlotte Maberly reviews a book about the search for wholeness, and a heartfelt plea to reclaim our spiritual, physical and emotional unity with nature

Book Review: “Work: A Deep History” by James Suzman

Richard Gault reviews a new book which takes a radical approach to contemporary work culture

Introducing… Bernardo Kastrup and Swami Sarvapriyananda

Charlotte Maberly appreciates a wide-ranging video conversation about Eastern and Western concepts of the self and mind

Connecting Threads on the River Tweed

Charlotte Maberly investigates an innovative project which explores cultural engagement as the driver of ecological change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

4 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

What a joy-filled article! Where each piece of factual information has a functional place in carrying the story forward, like a jig saw puzzle, that produces that satisfaction as the last piece is fitted in. The interweaving of the personal with the historical, arousing memories of the ferocious cold before central heating, and connecting the exploitation of environment and men, with the lawlessness of property and wealth accumulation.

I shall seek out her other writing with pleasure.

Thank you for the interview about the ethos of the magazine.

Plenty of ideas that chime with me and signposts of where to go next.

Beshara courses were mentioned how would l find out about them?

https://beshara.org/courses-events-21/

Please follow this link to find out about courses supported by the Beshara Trust

Thanks, conjures vivid images of bygone days