News & Views

Work: A deep history, from the stone age to the age of robots by James Suzman

Richard Gault reviews a new book which takes a radical approach to contemporary work culture

A group of Ju/’Hoansi-San, one of the last people on earth to live as hunter-gatherers. Suzman tells us that people in these societies work less than half the time that we do in the modern world, leaving them plenty of time for socialising and cultural activities like story-telling and art. Photograph: The Living Museum of the Ju/’Hoansi-San, Namibia. Niel Harris / Alamy Stock Photo

Many years ago, as part of a broader course on technology, I used to give a lecture on the sociology of work. I would begin by asking the students to guess what the most common form of work in our society is. In all the years that I posed the question I never once got the correct answer, which is housework. Why not? Well, simply because my students, like most people, equated work with being paid.

On another occasion, when at the receiving end of a talk on Islam, I heard some words of wisdom whose origin I have been unable to trace. The speaker cited something that sounded like a saying of the Prophet Muhammad. ‘Work,’ he told his audience, ‘is a gift sent by God so that people might meet one another.’ This offered a completely different understanding of the purpose of work. The primary purpose was not the extrinsic one of making something but the intrinsic one of promoting fellowship.

Of course, we would all agree that work is more than just making things. In fact, according to the author of this book, most ‘work’ – meaning paid work – these days does not yield a tangible product. In Britain today 83 per cent of the working population are employed in the tertiary, ‘service’ sector (p. 377). Of these some jobs are ‘genuinely useful, like teaching [and] medicine’ while others serve ‘no obvious purpose other than giving someone something to do [such as] corporate lawyers, public relations executives, health and academic administrators’ (p. 383). As an example of the rapid growth of what Suzman calls ‘bullshit jobs’, he notes that between 1975 and 2008 in California State University, the number of academics increased by a mere 3.5 per cent but administrative staff by 212 per cent. (p. 386)

How has it come to this, that we only recognise work as something we get paid for; that we do not emphasise its vital role in serving our soul, and that so much of what we do is of dubious real value? How is it that ‘the people we depend on to educate our children or nurse us when we are ill, for example, are now paid considerably less than those who make a living advising the wealthy to avoid taxation or who design new ways to spam us with endless unwanted advertising’? (p. 383).

One answer is simply that we have never been encouraged to ask these questions. Despite the centrality of work in everyone’s life, it is not itself a subject of any standard school curriculum. British children, for example, will learn much about long-dead kings but very little about the history of work despite their lives likely having much to do with the latter and little, if anything with royalty. We need to educate ourselves. This fascinating book by an anthropologist who has specialised in the study of hunter-gatherer societies offers us the means to do so.

Male Baya weaverbirds building a nest as the spring seasons starts. The males can build as many as 25 nests during a single season. Photograph: iStock

What is work?

Before embarking on the history of the work people do, Suzman prepares the ground for his study. He needs to define his key term – work. And to do this he goes back much further than the Stone Age, back to the origin of life itself over three billion years ago. Because as he sees it, ‘to live is to work’; all living things are distinguished by their harvesting and use of energy for a goal or an end. In his view, non-living things, like rocks and stars, do not harvest energy and so do not work (see pp. 8 & 27).

More radically, Suzman sets his ideas in a cosmological framework. The universe is governed by what he maintains is the ‘supreme law’, the second law of thermodynamics (p. 27). This ‘law’ dictates that there must be ever more entropy or disorder – disorder in the sense that there are increasingly fewer ways of distinguishing one thing from another, fewer ways of ordering them. Citing Erwin Schrödinger (he of the cat), Suzman states that organisms ‘are more energetic contributors to the overall entropy of the universe than objects like rocks’ (p. 33). I take a banana, which is easily distinguished from the chocolate bar you are enjoying. We both eat and then work, weeding the garden perhaps. In doing so the energy our food gave us is used up. Where has it gone? My banana and your chocolate have been burned up to give both the useful energy needed to work at weeding, and a waste energy, heat (we perspired, we exhaled warm air). The heat from the two sources cannot be distinguished and so we have added to the universe’s entropy.

Suzman argues that understanding that the universe is designed to foster entropy makes it clear why it gave birth to living beings. Leaving things to rocks and stars would be less efficient than creating life to churn out entropy (see p. 34). He asks: how did the universe manage to kick start life (and so work)? ‘It may have sprung from the finger of God, but far more likely it was sourced from the geochemical reactions that made early earth seethe and fizz’ (p. 33).

A universe geared to increasing entropy also explains the apparently senseless behaviour of creatures such as the African weaverbird which laboriously builds and dismantles nests – ‘around twenty-five […] in a single season’ (p. 47). He sees this as the bird’s way of expending surplus energy ‘in compliance with the law of entropy’ (p. 51). Suzman concludes that: ‘many hard-to-explain animal traits and behaviors may well have been shaped by the seasonal over-abundance of energy rather than the battle for scarce resources, and that in this may lie a clue as to why we, the most energy-profligate of all species, work so hard’ (p. 62).

Suzman then continues by describing how evolution has been directed to better ways of working, thus adding to entropy. Tools and the skills to use them clearly are important, and they are the subject of Chapter 3. The earliest tool was the 1.6 million year old enigmatic Achulean hand axe, which has probably been the most successful tool ever in terms of the length of time it was employed – 1.5 million years. It is enigmatic because despite its enduring popularity, it is unclear how it was actually used. A very special skill is language, so its emergence also passes under Suzman’s review, whilst the discovery of fire and its role in helping humans generate entropy is examined in Chapter 4.

Women in the Gambian rice fields, 2014. The author writes: ‘My first day in the rice fields in the Upper River Region of The Gambia, where I worked from sunrise until sunset. We worked until exhaustion, the young and the old, children on break from school and elders on break from prayers. Never have I ever experienced backbreaking work like this for such little reward – a small yield of rice for a family.’ Image: Wikimedia Commons

Foraging and Farming

.

There is much fascinating detail in Suzman’s opening chapters, and also much that one may disagree with (see my comments below). But the book really gets going when he starts to focus on his area of anthropological expertise, which is the history of (human) work during a period spanning the last 300,000 years. For 95 per cent of this time – the time our species, homo sapiens sapiens, has lived on this planet – we have worked as hunter-gatherers, or foragers, he tells us (p. 6). Suzman has lived amongst some of the very last peoples to live as foragers, the Ju|’hoansi of the southern African Kalahari desert, and based on his own experiences and that of others, together with historical and archaeological evidence, he describes what life and work was like for early hunter-gatherer societies.

The picture he paints is one of an Edenic existence. Foragers ‘spent on average less than half the time employed Americans spent at work, getting to work, and on domestic chores’ (p. 140). They enjoyed not just much more leisure time than us; they had such a ‘modesty of material requirements’ that ‘in their own way they were more affluent than a Wall Street banker who despite owning more properties, boats, cars, and watches than they know what to do with, constantly strives to acquire even more’ (p. 143). They lived necessarily in a close relationship with nature and they viewed it overwhelmingly as nurturing; they could always get what they needed ‘without much effort, much forethought, much equipment or much organization’ (p. 151). And as nature shared with them, they shared with each other. ‘Demand sharing’ meant it was not rude to ask for something from someone but certainly impolite to refuse a request (p. 152). So theirs was an egalitarian society where cooperation, not Darwinian competition, prevailed (p. 158). Furthermore, ecologically ‘hunting and gathering is by far the most sustainable economic approach developed in all of human history’ (p. 409).

So why did we abandon foraging and turn to farming about 10,000 years ago? [1] Why change? – if to farm was, as Suzman shows, to step out of Eden. The lives of pre-modern farming people, he writes, ‘were mostly shorter, bleaker… and tougher than those of their foraging ancestors.’ (p. 205). Where nature always provided for the forager, even in times of extreme drought (p. 139), the settled farmer was at the mercy of the vagaries of the weather and subject to pests and pathogens. (pp. 208–210). Frequently, they did not survive. ‘Depleted soils, diseases, famines, and later conflicts were recurrent causes of catastrophe in farming societies’ (p. 213). So the reason humanity turned to farming ‘remains something of a mystery’ (p. 180). Suzman suggests that perhaps a warming climate many millennia ago played a role (pp.186–9).[2]

But for whatever reason, the transition came about, and with it came fundamental changes in the way people engaged with their lives, each other and the world. ‘One of the most profound legacies of the transition to farming’, Suzman explains, ‘was to transform the way people experienced and understood time’ (p. 235 and Chapter 9). This is because for farmers, the future is always present in a way it is not for the foragers, who lived in the present or immediate future. Work for the farmer yields not immediate but delayed returns (see pp. 171, 185 and 231). Further, surpluses need to be built up in order to prepare for both the predictable – winters – and the unpredictable – possible crop failures, etc. So scarcity, which never bothered the forager, became a concern: more was now always better.

Time and work were therefore constantly needed to exploit domesticated spaces. Effort expended in ploughing fields, mending fences and guarding herds deserved reward, so the relationship with nature became transactional, Suzman explains (p. 239). This relationship extended to others: ‘Farmers with their delayed return economies saw their relationships with one another as an extension of their relationship with the land that demanded work from them’ (p. 247).

The view was that time was money, and the link between the two seemed obvious until a Scotsman demonstrated otherwise. Adam Smith showed in 1776 [3] that the value of something was not determined by the amount of work that went into producing it but by what someone was prepared to pay for it. The scarcer something was, the higher its price. With Smith, economics was born and a new way of understanding life. So the distinguished economist John Maynard Keynes could in all seriousness state 150 years later that the economic problem, that of scarcity, was ‘“the most pressing problem of the human race […] from the beginnings of human life”’ (p. 4, citing Keynes).

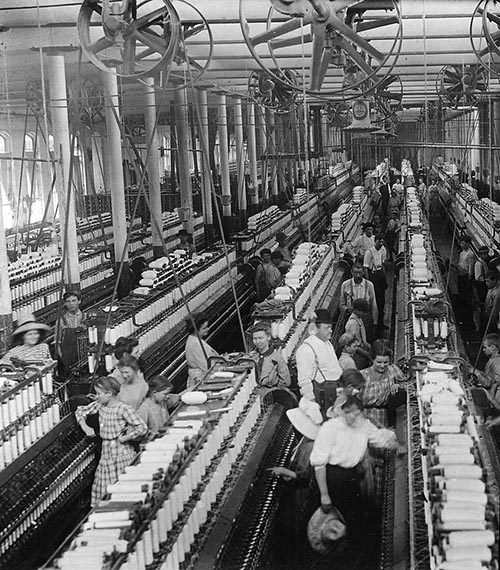

Interior of Magnolia Cotton Mills Spinning Room. Mississippi, 05/03/1911. Photograph: PF-(usna) / Alamy Stock Photo

Never Enough: The Curse of Artificial Scarcity

.

The breach between effort and reward became ever more apparent with the advent of machines, the industrial revolution and the growth of cities. The earliest city, Çatalhöyük [/], dates from around 9,000 years ago, but until the industrial revolution by far the majority of people lived and worked in the countryside. But since 2008, globally most people are now urban dwellers (p. 281). The development of cities enabled and required new types of work, Suzman explains, such as builders, engineers, police, and bureaucrats (p. 286). They also meant new types of relationships, with strangers for instance rather than fellow villagers, so that ‘traditional norms and customs dealing with reciprocity and mutual obligations couldn’t apply’ (p. 297).

The move from the countryside to cities, which began in Britain in the nineteenth century and has since enveloped most of the world, was a joint push–pull process. On the one hand new agricultural techniques and technologies (improved ploughs, better winter feed, new fertilisers) led to greater yields and so supported population growth while requiring fewer people to work the land (p. 309). On the other hand, the new steam-powered factories needed people to work in them and miners to supply their fuel. The new form of work was labour-intensive but required few skills, so workers were dehumanised. They toiled long hours and worked and lived in appalling conditions. Life expectancy fell in the first half of the nineteenth century in the UK (pp. 315–316).

However, in the latter half of the century, things improved sufficiently for people to have a little money to spend on luxuries: ‘It also marked the beginning of many people viewing the work they did exclusively as a means of purchasing more stuff, so closing the loop of production and consumption that now sustains much of our contemporary economy’ (p. 318). The change was in large part the result of workers organising themselves. However, it is notable, as Suzman points out, that trade unions have focused on improving pay and working conditions for their members and never campaign to make the work itself more fulfilling or more intrinsically rewarding (see p. 319).

Further important changes came about as the application of science led to radical developments in agricultural and production technologies, but until Frederick Taylor published his 1911 book The Principles of Scientific Management [4] science had never been directed at work itself. This work has been hailed as ‘the most influential management book of the twentieth century’ (p. 334). Taylor claimed that by studying and then standardising ways of working, maximum efficiencies could be achieved. Henry Ford hired him and Taylor’s scientific method proved itself; he cut down the production time of a Model T Ford from twelve hours to ninety-three minutes (pp. 332–3). But this came at the cost of deskilling the work, as the workers were treated as little more than machines: ‘it robbed workers of the right to find meaning and satisfaction in the work they did’ (p. 334).

However, the greater productivity that Taylor’s work enabled did lead to tangible benefits for more than just the factory owners. Working hours were reduced; by 1939, at 38 hours per week in the USA, these were less than half of those of a century earlier in British mills. Wages too rose. Taylor ‘was also the first to realise that in the modern era most people went to work to make money rather than products’ (p. 334–335). This insight was surprisingly, if not infamously, vindicated when workers employed by Kellogg’s campaigned successfully in the 1950s to have their weekly hours raised from 30 to 40 (p. 344).

Work meant money, and money meant the chance to nibble away at ‘the problem of scarcity’; the problem unknown to the foragers, painfully discovered by farmers, transformed into the raison d’être by economists and cleverly exploited by twentieth-century advertisers. Keynes’ expectation that the problem would be soon solved was foiled. His successor as the foremost economist of his own age, J.K. Galbraith, ‘believed that by the 1950s most Americans’ material desires were as manufactured as the products they purchased to satisfy them’ (p. 346). Nowadays, humanity seems cursed with what the sociologist Emile Durkheim named ‘the malady of infinite aspiration’ (p. 325).

The successful exploitation of the malady by the new profession of marketing (a ‘bullshit job’?) in large part explains why working hours have risen again since the latter part of the previous century (p. 340). But there is another possible reason. As Durkheim early recognised, ‘relationships forged in the workplace might help build the “collective consciousness” that once bound people into […] village communities’ (p. 371). People always seek fellowship. Whatever the reasons, more and more people are suffering as workaholics, ‘a real diagnosable condition with potentially fatal consequences’ (p. 368), and this despite ‘the overwhelming majority of workers across the world [not getting] a great deal of satisfaction out of their jobs […] just 15 per cent worldwide are engaged in their job’ (p. 387).

Automated Robot Arm Assembly Line Manufacturing of Advanced High-Tech Green Energy Electric Vehicles, 2021. Photograph: gorodenkoff/iStock

The Future of Work

.

The history of work that Suzman traces is a tragic one. And the future? Before us is AI, a potentially transformative technology which may ‘cannibalise the job market’ (p. 393), ‘As importantly, it will increase the returns on capital rather than labor’ and so could ‘entrench further structural inequality between [and] within countries’ (p. 394).

More universally, Suzman reminds us that humankind is facing a catastrophe greater than even those that regularly killed about half of European farming populations over the last 6000 years, such as the plague of the fourteenth century (see p. 210–12). In 1972 the Club of Rome warned ‘that our continued preoccupation with solving the economic problem was the starkest problem facing human-kind and that the likeliest outcome if things continued was catastrophe’ (p. 400). Fifty years on and finally the message is getting through but ‘the many initiatives aimed at addressing anthropogenic climate change and biodiversity loss have had to justify their existence in the very principles of economics responsible for them in the first place’ (p. 404).

Though Suzman states that the purpose of his book is not especially prescriptive, he does conclude by offering strong advice. We need, he states:

To loosen the claw-like grasp that scarcity economics has held over our working lives, and to diminish our corresponding and unsuspecting preoccupation with economic growth […] [itself] an artefact of the agricultural revolution amplified by our migration into cities (p. 412).

Office Work 2023. Photograph: Hero Images Inc. / Alamy Stock Photo

Conclusion

Suzman sets out to answer the questions I posed at the start: Why do we equate work with payment?; Why are the payment and the value of what work yields not closely related?; and Why is the intrinsic value of work overlooked? Furthermore, he shows how intimately the nature of work, and the nature of society as a whole, are bound up. In clearly revealing how the evolution of work has led to our current crises, he has done a great service. He may not have solved the problem of scarcity but simply recognising a problem goes a long way to solving it. It is interesting that the publication of his book coincides with another radical analysis of our economic and social system by anthropologists David Graeber and David Wendow, in The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity.[5] This equally overturns many of our preconceptions about hunter-gatherer societies and challenges the inevitability of human ‘development’ through the widely-accepted stages of foraging, farming and urban living.

Yet although Suzman’s account is coherent and persuasive, his own understanding of the problem is inadequate in my opinion. His thesis that life and work evolved as a way of generating entropy more effectively is novel, but he does not consistently draw on it when he turns to the history of work. He does not, for example, argue that farmers contribute to entropy more than foragers, or that factory workers do so more effectively than farmers.

He sets great store by the second law of thermodynamics. But what is this ‘law’? Calling a scientific principle a ‘law’ is at best to do so metaphorically. Nobody has ever been arrested for breaking a scientific law; any violation gets the law into trouble, not the ‘perpetrator’. These ‘laws’ are descriptive, not prescriptive. The danger with metaphors is that people may take them literally and that is what Suzman appears to have done when he writes that weaver birds ‘work in compliance with the law of entropy’ (p. 51, my italics). Elsewhere he speaks of ‘a universe governed by the laws of thermodynamics’ (p. 31) and approvingly paraphrases Schrödinger who believed that ‘life could not exist in violation of the second law of thermodynamics’ (p. 33). But the ‘law’ itself describes the behaviour of gasses in a closed, isolated system. It is quite a leap to then claim it is valid for the universe as a whole and although Suzman is not the only person to make it and anticipate the ‘heat death’ of the universe [/], it is a conclusion which is not universally accepted.

I would suggest that Suzman is somewhat muddled in his thinking here. On the one hand he apparently holds that there is a ‘supreme law’ which must be obeyed, but on the other he does not believe that there could be a law maker, law governor or law policeman: God for him is an unlikely possibility, as shown by the earlier quote on the origin of life. And what does he mean when he states that the earliest living organisms, cyanobacteria, once established ‘set to work transforming the earth into a macro-habitat capable of supporting far more complex life’ (p. 36)? It sounds as if cyanobacteria had a plan but I do not think this is what he actually believes.

In fact, rather than being an advocate of intelligent design, Suzman appears to support the ‘mechanical view of nature’ held by the author of the second law, Ludwig Boltzmann (p. 31). This is betrayed by the fact he cites Boltzmann approvingly and by his definition of work mentioned earlier, ‘expending energy […] to achieve a goal or end’ (p. 8). Only the extrinsic result of work is mentioned in this definition; the intrinsic benefit is not. Despite this, Suzman does recognise that work can, perhaps should, be satisfying as when he notes that trade unions did not campaign for work to be more fulfilling and criticisms of Taylorism. However, these are largely en passant remarks with little if any attempt to explore the consequences further.

Another writer I have reviewed (click here) has also written on the changing character of work. In his magnum opus The Matter with Things, Iain McGilchrist illustrates how there is more to work than what you harvest. This is how he describes a scene that he witnessed once while on a holiday in Greece:

The local farmer’s olives are now gathered in in one morning by a gang of eight men, each armed with a machine. In the past it would have taken the family, men, women and children, three days to do the same work. How wonderful is that? Well, it depends what you think life is about. Picking olives with friends and family was a companionable event. It involved singing and laughter. It brought together communities across the generations. […] It would be punctuated with pauses to sit, chat, eat and drink. It had a meaning which is difficult to convey, surrounding the relationship between the often-ancient trees, a proper reverence for them, their harvest, and its place in Greek culture, the process of gathering in something in the nature of a gift, in the peace of the autumn landscape, that would be stored and enjoyed over the whole coming year. It is also true that the olives were more carefully harvested, and there was less detritus… that got into the mash. But it’s more about what it does to us and our relationship with nature than to the oil. A generative experience has been turned into a sort of violation: this was in fact the word used by the woman whose trees were being harvested in the village yesterday.[6]

Unlike Suzman, McGilchrist focusses on the intrinsic value of work – work as something worthwhile, as having meaning, in itself.

Suzman’s analysis is thus incomplete because of the flawed foundation upon which it rests. The problem of work is not simply the problem of scarcity. The root of the problem lies even deeper, bound up with the acceptance of a mechanical, materialistic world view. Regarding the purpose of work as solely that of achieving extrinsic ends and ultimately as a means of hastening the heat death of the universe is a pretty miserable – literally dispiriting – understanding. Far better, and truer I would contend, is to see work as activity we perform in order to enrich our souls and which we achieve in large part by enriching the souls of others. It can be a holy act. Can’t weaverbirds build nests simply for the joy of exercising their talent?

Despite my reservations, if I could, I would insist that every college student read this book, providing that it is introduced and studied with the qualifications I have set out. Young people deserve to know how the world they are entering came about so as to be better prepared for it. But Suzman is only half-right in his conclusion that ‘recognising that many of our core assumptions that underwrite our economic institutions are the artefact of the agricultural revolution […] frees us to imagine a whole range of new, sustainable possible futures for ourselves’ (p. 412). The failure of the mechanistic world view needs to be recognised too if catastrophe is to be avoided and a future of rewarding work achieved.

Work: A deep history, from the stone age to the age of robots by James Suzman was published by Penguin Books in 2022.

Sources (click to open)

[1] JAMES SUZMAN, Work (Penguin Books 2022).

[2] Although the break between foraging and farming is not as sharp as Suzman’s account might seem to imply. The recent article in the magazine ‘Eating The Wild’ notes how until a few centuries ago farmer communities supplemented their diets with what nature offered. However, Suzman’s general point remains: farming communities lived and worked in a radically different way from foraging peoples.

[3] ADAM SMITH, An Enquiry into the Wealth of Nations (Oxford University Press, 1776)

[4] FREDERICK WINSLOW TAYLOR, The Principles of Scientific Management (Harper & Brothers, 1911).

[5] DAVID GRAEBNER and DAVID WENGROW, The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (Penguin, 2022).

[6] IAIN McGILCHRIST, The Matter With Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions and the Unmaking of the World (Perspectiva Press, 2022), p. 938.

Dr Richard Gault has worked at universities in Scotland, Ireland, Holland and Germany, where he has taught and researched a variety of subjects, including the history and philosophy of science and technology. He is a long term student of the Beshara School and from 2015–17 was principal of The Chisholme Institute in Scotland.

More News & Views

Poems for These Times: 18 – New Year 2024

Benjamin Zepahniah | Faceless

“You have to look beyond the face

to see the person true

Down within my inner space

I am the same as you…”

Introducing… ‘Tiger Work’ by Ben Okri

Barbara Vellacott reads from and discusses a new book of stories, parables and poems about climate change

Book Review: “Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time” by Kapka Kassabova

Charlotte Maberly reviews a book about the search for wholeness, and a heartfelt plea to reclaim our spiritual, physical and emotional unity with nature

Introducing… Bernardo Kastrup and Swami Sarvapriyananda

Charlotte Maberly appreciates a wide-ranging video conversation about Eastern and Western concepts of the self and mind

Connecting Threads on the River Tweed

Charlotte Maberly investigates an innovative project which explores cultural engagement as the driver of ecological change

The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth

Jane Clark | reviews a book about the effects of climate change on the great boreal forest at the top of the world

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Thank You Richard for your precious time and talent sharing your news and views. Appreciated. Love and Light.

J.Dupre

t

I found the review to be fantastic, thank you Richard