News & Views

Henry Moore: The Helmet Heads at the Wallace Collection

Johnathan Sunley reviews a thought-provoking exhibition of sculptures in London

View of the installation, reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation. Photograph © The Wallace Collection

Think of the Wallace Collection and perhaps what comes to mind is the magnificence of the building in which it is housed, which used to be a grand private residence; or some of the paintings for which it is famous – The Laughing Cavalier by Frans Hals, for example, or Fragonard’s The Swing. But the Collection is also home to three rooms of European arms and armour dating mostly from the medieval and early modern periods. Less well-known they may be, but many of the items in these galleries – pistols, swords, shields, suits of armour – are beautifully made and close to being works of art in their own right. And even if this is not the intention, their very presence in the museum could be regarded as raising pertinent questions about the relationship between warfare and wealth.

It is to these rooms that the English artist Henry Moore (1898–1986) returned again and again. There is evidence that his first visit was in the 1920s, while we know from one of his sketchbooks that he made what may have been his last visit in 1972. As he told an interviewer towards the end of his life: “The idea of one form inside another form may owe some of its incipient beginnings to my interest at one stage when I discovered armour. I spent many hours in the Wallace Collection, in London, looking at armour.”

What really sparked Moore’s imagination were the helmets he saw. This fascination led to a large number of semi-abstract drawings in which heads and helmets morph into each other, and to a remarkable sequence of sculptures exploring the same theme. Until this exhibition, these sculptures – known collectively as “the Helmet Heads” – had never been displayed together. On show among them are helmets in various styles from the Collection itself, making it possible to see what inspired Moore in the first place.

The Helmet (1939–40), from The Henry Moore Foundation: gift of Irina Moore 1977. Photograph © The Henry Moore Foundation.

One Form Inside Another

.

What was it about these objects that Moore found so compelling? Clearly a great deal of skill went into designing and producing them. But is there not something rather sinister about their appearance? Menacing, even? These are not words we usually associate with Moore. The works on which his reputation rests are imbued with a sense of landscape, nature and the feminine that carries over into their emblematic titles. What have Mother and Child or Reclining Woman to do with the world of medieval battle in which an armour-clad combatant fights for his life?

Moore himself knew about the experience of war, having served as a soldier in World War I. One of the helmets shown in the exhibition is the British Army ‘salad bowl’, of a type which he himself would have worn while fighting as a machine-gunner at the Battle of Cambrai in 1917. It did not, however, prevent him from being gassed. One way of approaching his Helmet Head sculptures, therefore, is to view them as a pacifist statement about the dangers of war in an age in which the technology of modern weaponry (its ‘lethality’, as might be said today) is such that there can be no protection against it. On this reading, their skull-like form suggests a death’s head while their overall purpose is like that of any memento mori.

You do not have to spend long looking at these sculptures to see that there is much more to them than this. Skull-like in some respects they may be. But, whereas the human skulls we might encounter in an anatomy class or museum cabinet are always empty, and in this sense similar to a helmet, Moore’s Helmet Heads are not empty at all, consisting of an internal, often biomorphic figure of some sort enclosed in a smooth, rounded carapace. A relationship between these two forms – one strong, the other more fragile and vulnerable – is implied that brings the sculptures to life. It is as though we are looking at one of the medieval helmets displayed in the exhibition and suddenly become aware of the presence of the person who once wore it.

The idea of one form inside another always interested Moore and over the course of a long career he gave expression to it in numerous works – on paper, in stone and in bronze. In The Helmet (see above), it is hard not to see another iteration of the mother-and-child motif that meant so much to Moore, albeit that the childlike figure in this sculpture could be viewed as being held not so much within its mother’s body as her mind.

Helmet Head No.1 (1950), from the Tate, London. Photograph ©Tate, London 2018. Artwork reproduced by permission of The Henry Moore Foundation

In Helmet Head No. 1, by contrast, the inner form is a sharpened, cone-like structure that some critics have compared to a dagger. Moore made this sculpture not long after the end of World War II and may well have intended a reference to this conflict. But others have picked up on the geometric quality of this cone and speculated about an acknowledgement on Moore’s part of his debt to the ancient Greeks, or to non-Western traditions of sculpture in which there is often more emphasis on ideal geometric forms.

Helmet Head No. 6 (1975) from The Henry Moore Foundation: acquired 1987. Photograph © The Henry Moore Foundation

A much later work in this series, Helmet Head No. 6, seems less ambiguous than the others in the way it treats the subject of emergent life. Here most of the outer casing is cut away, revealing inside a bird-like creature with folded wings that, as the catalogue to the exhibition notes, “may be hatching from its egg-like shell or escaping from a cage”.

Erich Neumann’s book The Archetypal World of Henry Moore came out some fifteen years before the making of this particular sculpture. But there is a passage in it in which the philosopher and analytical psychologist offers a Jungian perspective on Moore’s mother-and-child imagery that might very well have been written about this work:

The image [is] known all the world over, of the soul that comes into the body from outside and dwells in it as in a cave or shell. […] An analogous idea is that of the soul departing at death in the shape of an animal and thereafter leading an existence independent of the body (p. 55).

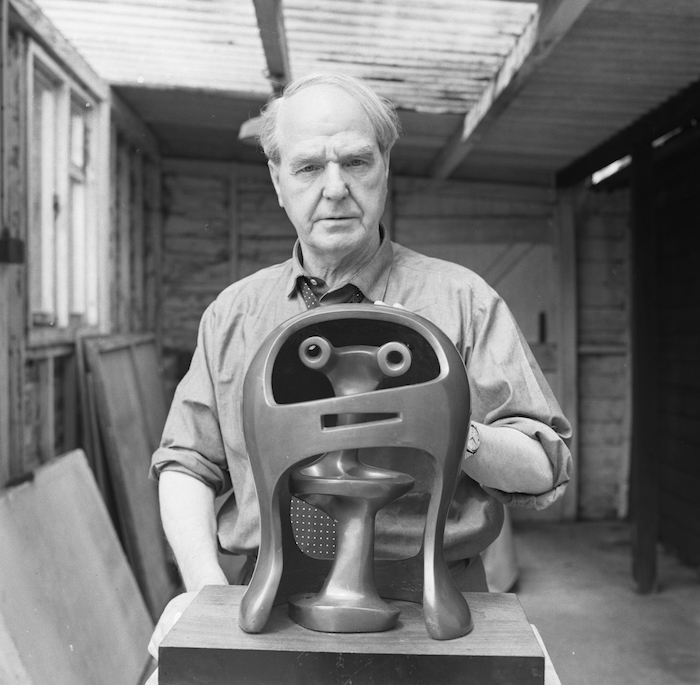

Portrait of Henry Moore with Helmet Head No. 2. Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation.

The Mystery of Being Human

.

Working as a psychotherapist, I may sometimes find myself wondering about the souls of my patients. I might sometimes reflect on the shape of my own soul too. But it is their heads that have a greater impact on me on a day-to-day basis, both as I am faced by them in a literal sense and as I ask myself what might be going on in them. At the same time, I recognise that this is just a metaphor. For there is really no more reason to think of a person’s thoughts, feelings, dreams or memories being ‘inside’ them than ‘outside’ them. My task, as I understand it, is not to see inside the heads of my patients but, by carefully contemplating how they look and sound, to see, as it were, from them. As Wittgenstein puts it so beautifully: “The human body is the best picture of the human soul.”

For me, Moore’s Helmet Heads are both extraordinarily powerful and faintly disturbing in the way that they capture something of this paradox or mystery of being human. As we have seen, they are made up of two forms, where the outer one appears to be protecting an inner entity, much as a steel helmet protects a head or the shell of a crab or snail gives protection to the creature within. Only so organic is the relationship between these entities that in many cases it is impossible to differentiate them, while the sculpture as a whole is comprised to such an extent of spaces and openings that it becomes equally difficult to know whether we are looking at it from outside or coming to know it from within.

A more recent book about Moore by the art critic Peter Fuller barely mentions these works, but he is in no doubt at all about the scale of his achievement in terms of enabling us to understand ourselves better. He writes:

The originality of Moore’s contribution within the sculptural tradition cannot be doubted, but the significance of his work extends beyond the history of art. Although resolutely secular, Moore’s sculpture constitutes one of the most commanding spiritual affirmations of our time (p. 1).

The Helmet Heads can be seen at the Wallace Collection until 23rd June 2019. See https://www.wallacecollection.org for more information

Sources (click to open)

TOBIAS CAPWELL & HANNAH HIGHAM: Henry Moore: the Helmet Heads, London: Philip Wilson, 2019.

PETER FULLER: Henry Moore, London: Methuen, 1993.

ERICH NEUMANN: The Archetypal World of Henry Moore, trans. R.F.C Hull, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1959.

Johnathan Sunley is a psychotherapist and writer who lives in London.

More News & Views

Poems for These Times: 18 – New Year 2024

Benjamin Zepahniah | Faceless

“You have to look beyond the face

to see the person true

Down within my inner space

I am the same as you…”

Introducing… ‘Tiger Work’ by Ben Okri

Barbara Vellacott reads from and discusses a new book of stories, parables and poems about climate change

Book Review: “Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time” by Kapka Kassabova

Charlotte Maberly reviews a book about the search for wholeness, and a heartfelt plea to reclaim our spiritual, physical and emotional unity with nature

Book Review: “Work: A Deep History” by James Suzman

Richard Gault reviews a new book which takes a radical approach to contemporary work culture

Introducing… Bernardo Kastrup and Swami Sarvapriyananda

Charlotte Maberly appreciates a wide-ranging video conversation about Eastern and Western concepts of the self and mind

Connecting Threads on the River Tweed

Charlotte Maberly investigates an innovative project which explores cultural engagement as the driver of ecological change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Mary Oliver reading Wild Geese

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

0 Comments