Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 25, 2023

Personal Integrity in the Poetry of C.P. Cavafy

Andrew Watson pays homage to Greece’s most famous modern poet, whose message of quiet fidelity to one’s own values still has great resonance today

Personal Integrity in the Poetry of C.P. Cavafy

Andrew Watson pays homage to Greece’s most famous modern poet, whose message of quiet fidelity to our own values still has great resonance today

The current world situation, with war raging in the Middle East and Ukraine, presents a particular challenge to those people who wish to take a unified perspective – one which goes beyond polarities and tribalism in search of justice and humanity. It is hard to know how to respond. At such a time, the gentle but insistent voice of Constantine Cavafy, the modern Greek poet, carries a welcome reminder that however extreme the external circumstances, there is always the path of keeping faith with the values and principles we know to be true. Although much of his poetry is based overtly upon the events and myths of the ancient world, editor and translator Andrew Watson, who has recently worked on a comprehensive new book about him for the Onassis Archive in Athens, explains that Cavafy’s underlying message is an eternal one, based upon a deep understanding of the human condition.

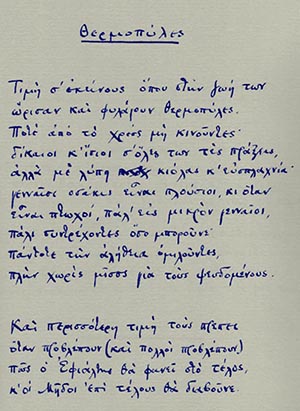

Honour to those who in their life

define and guard a Thermopylae.

Not betraying what is right,

consistent and just in all they do

but showing pity also, and compassion;

generous when rich, and when poor

still generous in small ways,

still helping others as much as they can;

always speaking the truth,

yet without hatred for those who lie.

And even greater honour is due to them

when they foresee (as many do foresee)

that Ephialtes the traitor will appear in the end,

and the Persians will break through after all. [1]

This poem, entitled ‘Thermopylae’, was written in Greek in 1900. It has as its theme the heroic stand of the Spartan defenders against the mighty invading Persian army at the narrow pass at Thermopylae in 480BC, which ended when they were betrayed by the traitor Ephialtes, and the Persians ultimately – and inevitably – broke through. The setting of the poem is ancient history, but the meaning is timeless: the need to be true to one’s own values, whether or not the conditions are propitious, and even if failure seems inevitable.

This poem, entitled ‘Thermopylae’, was written in Greek in 1900. It has as its theme the heroic stand of the Spartan defenders against the mighty invading Persian army at the narrow pass at Thermopylae in 480BC, which ended when they were betrayed by the traitor Ephialtes, and the Persians ultimately – and inevitably – broke through. The setting of the poem is ancient history, but the meaning is timeless: the need to be true to one’s own values, whether or not the conditions are propitious, and even if failure seems inevitable.

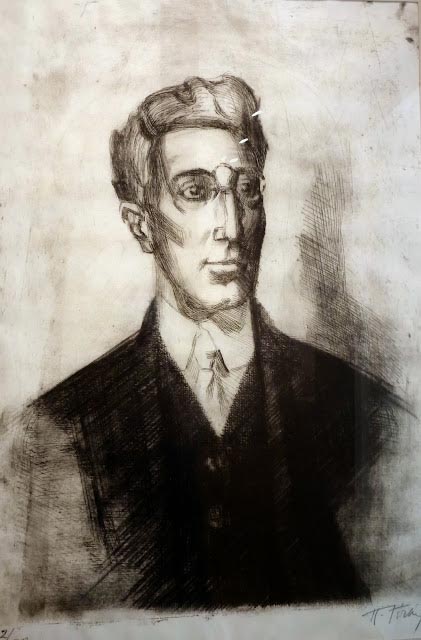

It was written by Constantine (C.P.) Cavafy (1863–1933), generally considered to have been the most significant Greek poet of the 20th century, and certainly the best known outside Greece. The poem is representative of much of his work: the ancient Greek setting, the quiet reflective tone, the unsentimental appeal to private integrity while also acknowledging the seeming futility inherent in much of human endeavour. Written in the first year of the twentieth century, it seems to have particular prophetic relevance to a century in which so many fell victim to inexorable and implacable forces against whom resistance often seemed futile.

Cavafy’s international fame has inevitably been mediated through translation, as Modern Greek remains a relatively little-known language; he is in fact the most translated modern poet in the world today. One undoubted reason for his appeal to translators, and to readers in general, is the understated and direct nature of his verse: it is often simple and clear in style, and generally readily comprehensible. Though a knowledge of ancient Greek history and mythology is helpful, his language and imagery do not have the obscurity and complexity that characterise the work of many important modern poets.

At a Slight Angle to the Universe

.

Cavafy himself spent very little time on the territory of modern Greece: he was born and lived most of his life in Alexandria, the great Mediterranean port of Egypt, where his parents had settled in the middle of the 19th century. The city, which provides the setting of many of his poems, was home to a large and prosperous Greek community, which thrived in its cosmopolitan and commercial atmosphere until most of them chose to leave after the Arab nationalist revolution in the 1950s. Cavafy was a private, introverted man, who lived in relative seclusion, refusing to publish his work formally and preferring to share it through local newspapers and magazines, or to print it out himself and circulate it among friends. He worked for most of his life as a clerk at the Egyptian Ministry of Public Works, and lived an outwardly uneventful and ordered life. He has the peculiar distinction of having died on his 70th birthday, on the 29 April 1933; at the time of his death there was little sign of the worldwide fame and recognition he would subsequently receive, and of which he himself was always distrustful in his lifetime.

The other great cultural influence in his life was that of England. He spent many years of his childhood and adolescence in Liverpool, where the Cavafy family had a trading house, and he wrote and communicated as freely in English as he did in Greek. Some of his earlier poems were actually written in English, and English literature in general had a significant influence on his work. It has even been suggested that something of his ironic detached voice was due to this English influence. Though this is debatable, the tone and expression of his poetry is quite distinct from that of other modern Greek poets.

Although his loyalty was always to his own people, he remained throughout his life something of a liminal figure: a ‘European’ poet who lived in Africa; a Greek who spoke his own language with a slight English accent; a writer whose poetic language fused older and modern forms of Greek; a homosexual, who was deeply private and reserved even with his closest friends; a poet whose work is set primarily in a historic past, but who articulated an understanding of the human condition which is representatively modern. Cavafy’s friend E.M. Forster, the novelist and literary critic, when introducing his poems to the English-speaking world in 1923, famously described him as ‘a Greek gentleman in a straw hat, standing absolutely motionless, at a slight angle to the universe’.[2] He seems always to be observing life from the outside, with a mixture of detachment, insight, sensuality, and melancholic resignation.

Dignity in the Face of Failure

.

Another great poem, written in 1911, is ‘The God Abandons Antony’, which takes as its theme Plutarch’s [/] story of how Mark Antony [/], besieged in Alexandria [/] in 31BC, heard the sounds of a supernatural ghostly procession making its way through the city. He knew that this meant that his protector, the god Dionysus [/], was deserting him, and his dreams of power and glory were at an end. Cavafy may have been inspired by the scene in Act IV of ‘Antony and Cleopatra’, where Shakespeare writes that ‘music of the hautboys is under the stage’, indicating that the god ‘whom Antony loved/Now leaves him’.[3]

When, all at once, at midnight, you hear

an invisible procession passing by,

with exquisite music, with voices,

do not vainly mourn your fortune

which now gives out, the failure of

your labours, your life’s plans having all proved false.

As one long prepared, and without fear

Bid her farewell, this Alexandria that is leaving you.

Above all do not fool yourself, do not say

it was a dream; your hearing was deceived.

Do not give way to empty hopes like these.

As one long prepared, and without fear,

as befits a man who was worthy of such a city,

go resolutely to the window

and listen, with deep emotion, but not

with a coward’s entreaties and laments,

to the sounds – a last delight –

the exquisite instruments of that mysterious procession,

and bid farewell to her, the Alexandria you are losing.[4]

Here again there are typical Cavafian themes: the power of beauty to console and give meaning, or else to deceive; the tendency of dreams and ambitions to remain unfulfilled; stoic dignity in the face of failure. Again it concerns a historical figure from the classical past, but the message is enduring: the pronoun ‘you’ invites us to see ourselves in the place of Antony, contemplating our own failure, but asked to accept our destiny with dignity and clear-sightedness.

The poem also seems to foreshadow the catastrophic defeat of the Greek army to the Turks ten years later, in 1922. This was an existential disaster which finally put an end to the long-held Greek dream of regaining control over ancestral homelands in Asia Minor. The subsequent population exchange led to over a million Greeks bidding farewell to lands they had lived in for over 2,500 years. The distant past and the present are always intimately entwined in Cavafy’s imagination – as well as the looming uncertainty of the future.

As Much as You Can

.

The full canon of Cavafy’s poems numbers only around 150, though they have been supplemented by other poems which he suppressed or repudiated and which have subsequently come to light. Some of his contemporary fame is thanks to his so-called ‘sensual poems’ which describe erotic encounters in direct, unsentimental terms, and have led to him being seen – particularly since the 1960s – as a poet of sexual liberation and unapologetic hedonism. But Cavafy’s theme is not the search for pleasure. He accepted his own sexuality, and indeed stated that erotic experience had nourished his verse, but he is nonetheless a moralist – though his morality is always centred on fidelity to what one knows to be true or right, against the enticements of public acclaim or social success. He reiterates this in a short cautionary poem, ‘As Much as You Can:

And if you cannot make your life as you wish

try to do this at least,

as much as you can: do not cheapen it

with too much contact with the world

with too much activity and chatter.

Do not cheapen your life, dragging it here and there,

exposing it to the daily nonsense

of social networks and gatherings

until it becomes a dead weight that you carry around.[5]

The power of this simple poem is in its stark evocation of a condition all can recognise: the compromises one makes in order to gain acceptance in the world, with the implicit threat of ultimate alienation from one’s true self. Being lost or damned is not presented here in Christian terms, but it has a comparable resonance, suggesting that blindly pursuing social success on any terms can end in a secular form of damnation.

The same theme of personal compromise for the sake of worldly glory is found in the poem ‘The Satrapy’, written in 1910. A satrap was a provincial governor in the Persian Empire, and the poem speaks of the fate of a cultured Greek who abandons his own principles and values in order to ingratiate himself with the Persian king Artaxerxes, and seek a position of power among the alien Persians – giving up everything that is of real value to him. The historic figure on whom the narrative is based is almost certainly the Athenian leader Themistocles (c. 524 – c. 459 BC), who could not endure his loss of prestige among his own people and in his final years chose instead to pay court among his former enemies, the Persians.

What disaster, when you were made

for fine and noble works,

that this unjust fate of yours always

denies you recognition or success;

and you are thwarted by trivial conventions,

pettiness and indifference.

And how terrible is the day when you finally give in

(the day you surrender and give in),

and make your way to Susa,

and go before the monarch Artaxerxes

who magnanimously grants you a place at court,

and offers you satrapies, and that sort of thing.

And you accept them in despair –

these things you do not seek.

Your soul wants other things, weeps for other things:

the praise of the Demos and the Sophists,

their hard-won and inestimable acclaim;

the Agora, the Theatre, and the laurel crowns.

How can Artaxerxes give you these?

Where will you find them in a satrapy?

And without them, what sort of life can you live? [6]

The subtle fusion of ironic mockery with genuine sympathy for Themistocles’ plight is typically Cavafian, puncturing the vanity that has led him to prostitute himself in a foreign land while reminding us that his talents and abilities were genuine, not simply imagined, and his sense of being denied his just reward is understandable. Themistocles’ real failure lies in his inability to accept public obscurity as a price for remaining true to what really matters to him.

Journeying

.

The darker implications of this vision are made explicit in another important poem, ‘The City’, written in 1910. Here Cavafy again adopts the same straightforward, didactic tone to warn against deluding oneself about one’s destiny and the possibility of creating oneself anew. Again it is the city of Alexandria that comes to stand as the universal city of our imagination – the place in which we all find ourselves, wherever we are, and however painful that process of self-knowledge is. In no other poem does Cavafy make the despair that underlies his stoicism more unambiguous.

You said: “I will go to another land, another sea:

Another city I will find, better than this.

Here everything I attempt ends by condemning me

And my heart – like a corpse – is buriéd.

For how long will my mind moulder in this place?

Wherever I turn my eye, wherever I gaze,

I see the blackened ruins of my life,

Where so many years I have spent, wasted and lost.”

You will not find new lands; you will not find new seas.

The city will follow you. Through the same streets

you will wander: you will grow old in the same neighbourhoods,

And turn grey in the same houses.

Always to this same city you will come. As for elsewhere – do not fool yourself:

There is no ship for you, there is no road.

Just as you wasted your life here,

In this little corner of the world, so you ruined it everywhere.[7]

The poem recalls the famous line of the Roman poet Horace, Caelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt (‘Those who hurry over the sea change their sky, not their souls’).[8] Yet Cavafy does not only leave us this bleak vision. It is always possible within the constraints and imperfections of our lives to follow a life of private principle and commitment, if we accept ourselves as we are, and do not allow our values to be dictated from outside.

His most famous work, which often appears in modern anthologies of ‘favourite poems’, is probably ‘Ithaca’. In this case his inspiration is drawn from Homer – Odysseus’s long and eventful journey to return to the island of his birth – as well as the Mediterranean world in which Cavafy himself lived, but it conveys a general lesson about human life which has particular relevance to modern times. Once again he uses the pronoun ‘you’, inviting us to see ourselves in the place of Odysseus – implicitly moving the context into the present day. The Laestrygonians and Cyclops and the god Poseidon have here become representations of inner demons, psychological conditionings, as threatening to our own journey through life as the originals were to Odysseus. Perhaps they also represent the agents of repression that exist in every human context, and especially in societies which are not free and where public conformity is coerced. Our task is not to be intimidated, and to remain true to the dictates of our true self, as much as we can.

When you set out on the journey to Ithaca

ask that the road be long,

full of adventure, full of learning.

The Laestrygonians, the Cyclops,

and angry Poseidon — do not fear them:

such things you will not meet on your way

so long as your thoughts are never base,

so long as rare emotion

touches your spirit and your body.

The Laestrygonians, the Cyclops,

wild Poseidon — you will not meet them,

unless you allow them into your soul,

unless your soul raises them up before you.

Ask that the road be long.

That there be many summer mornings when,

with what delight, what joy,

you enter harbours seen for the first time:

may you call at Phoenician trading stations

and purchase the finest merchandise,

mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony,

sensual perfumes of every sort –

as much sensual perfume as you can find.

May you visit many Egyptian cities

and learn and learn from those who know.

Keep Ithaca always in your mind.

Your arrival there is your goal.

But do not hurry your journey at all.

Better that it last for many years,

and you moor at the island an old man,

rich with all you have gained along the way,

not expecting Ithaca to give you riches.

It was Ithaca that gave you the marvellous journey.

Without her you would not have set out.

She has nothing more to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaca has not deceived you.

Wise as you have become, with such experience,

You will already have understood what these Ithacas mean. [9]

It is not the final success of the journey that is important: indeed it is highly likely that the destination will prove disappointing or unattainable. In any case the fact of death means that all journeys inevitably end in the same ultimate dissolution. What matters is the spirit in which the journey is undertaken: the desire to observe, to learn, to seek beauty, to take time, to follow one’s own path and remain faithful to it.

Although Cavafy died 90 years ago, he continues to speak with particular relevance to the human predicament in the modern age, and particularly so after the catastrophic failure of the grand idealistic projects (not only Greek ones) that inspired and ultimately betrayed mankind in the course of the 20th century. His vision arises (in part) out of a particular interpretation of ancient history, which he understood not as a succession of triumphs, but as a salutary warning about human limitations and the capacity for self-delusion. However Cavafy does not respond to this truth about the human condition simply with cynicism or despair. Instead he reminds us that there is always the way of quiet fidelity to one’s own values, which do not depend for their justification on worldly success or glory. Whatever the imperfections of the time and place in which one finds oneself, the corruption of the world around us, or the disappointments and failures of one’s own life – the attempt to remain faithful, as much as possible, to what one knows to be true is of value in itself.

All translations of Cavafy’s poems are the work of the author.

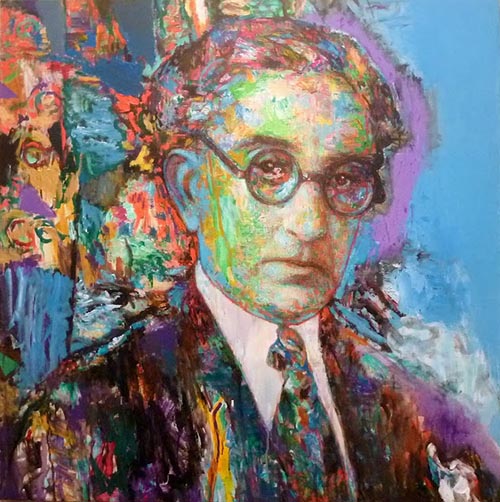

There are several English translations of Cavafy’s poems, but we mention this one in particular, translated by Edward Keely and Philip Sherrard (Chatto and Windus, 1990). Its cover image is a portrait of Cavafy by David Hockney.

There are several English translations of Cavafy’s poems, but we mention this one in particular, translated by Edward Keely and Philip Sherrard (Chatto and Windus, 1990). Its cover image is a portrait of Cavafy by David Hockney.

The Onassis Cavafy Archive is an open source resource which contains more then 2,000 documents, including photographs of Cavafy and his circle and copies of original texts. For access, click here [/].

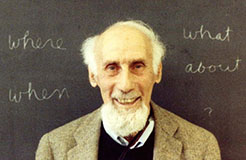

Andrew Watson is an editor and translator, particularly of Modern Greek. He has a long connection with Greece going back to the 1980s. Previously he worked for many years as a lexicographer at the Oxford English Dictionary. He has recently translated a book on Cavafy which covers all aspects of his life and writing for the Onassis Cavafy Archive [/]. This will appear in due course online.

Image Sources (click to close)

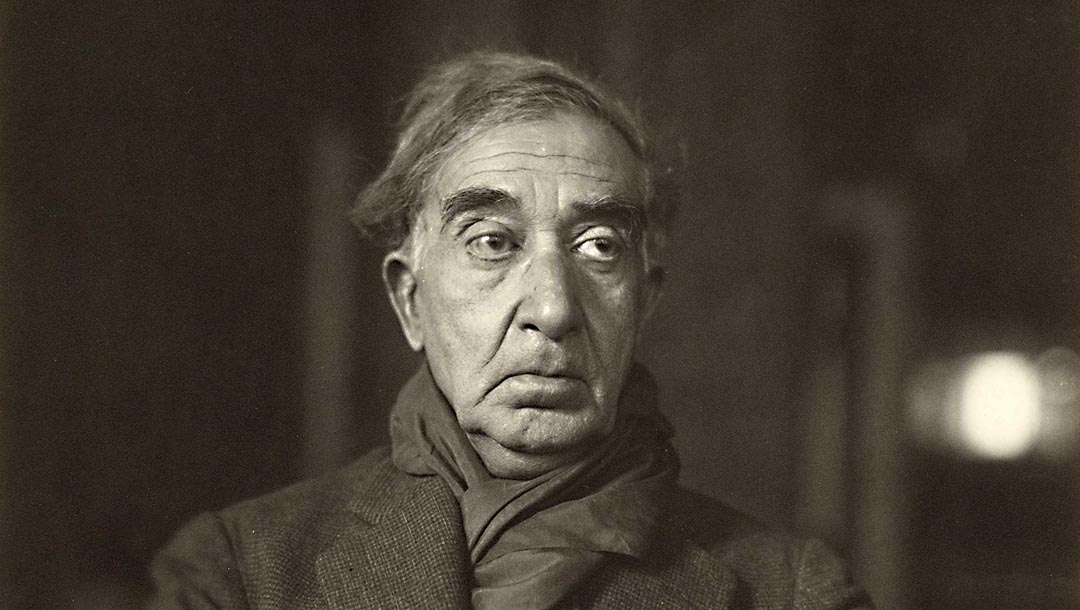

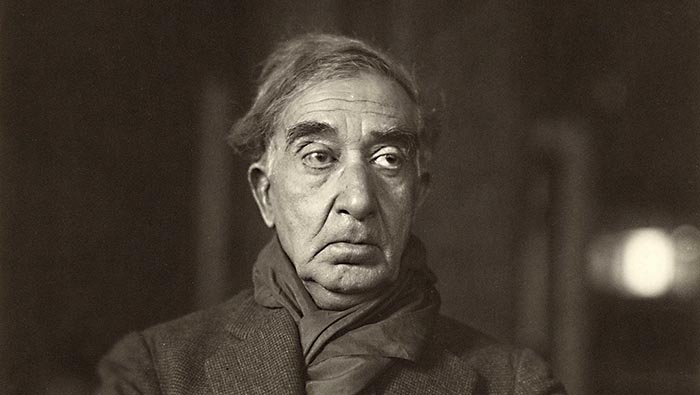

Banner: Portrait of C.P. Cavafy taken in 1932, towards the end of his life in the workshop of the sculptor Michalis Tompros in Athens. The poet is recovering from a tracheotomy operation he underwent. Photograph: From the Onassis Cavafy Archive [/].

Inset: The original written text of ‘Thermopylae’. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] C.P. CAVAFY, Poems I (1896–1918) (Ikaros Publishing House, 1963) p. 103.

[2] E.M. FORSTER, Pharos and Pharillon (Hogarth Press, 1923), p. 91.

[3] WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, Antony and Cleopatra, Act IV, sc. iii. pp 22-23.

[4] C.P. CAVAFY, Poems I (1896–1918), p. 20.

[5] C.P. CAVAFY, Poems I (1896–1918), p. 25.

[6] C.P. CAVAFY, Poems I (1896–1918), p.16.

[7] C.P. CAVAFY, Poems I (1896–1918), p. 15.

[8] HORACE, Satires and Epistles (University of Oklahoma Press, 1974), Epistle I. xi. (line 27).

[9] C.P. CAVAFY, Poems I (1896–1918), p. 23.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Stefan Sperl: Faces of the Infinite

Stefan Sperl talks about about his project on Neoplatonism and the poetic traditions of Europe and the Near East

Robert Lax: A Life Slowly Lived

The contemplative practice of a remarkable 20th-century poet/mystic — by Robert Hirschfield

George Swede: Haiku Master & Secular Contemplative

Robert Hirschfield talks to the Canadian poet and psychologist

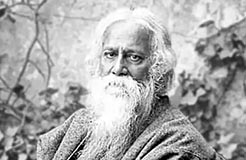

Participating in the Divine Playfulness

Hina Khalid explores the Theological Aesthetics of Rabindranath Tagore

READERS’ COMMENTS

This is a beautiful account of Cavafy and his poetry, sensitively written and sensitively thought. Thank you! In these troubled and troubling times, Cavafy is a voice of sanity, compassion and quiet humanity.

Cavafy is one of those rare, sensitive individuals who brought the ancient wisdom tradition forward to those in his lifetime. Thank you, Andrew, for bringing it to us. ‘Thermopylae’ proffers wise counsel to not be overwhelmed by the current happenings in this crazy world of ours.

Terri

ps I seem to recall an observation by Thucydides In his Peloponnesian Wars on traits that used to be admired –altruism, kindness, loyalty–became despised, while those traits that were once despised–greed, killing, stealing– became admired but never could find the exact source.

The excellent article by Andrew Watson, an expert on all things Greek, bring and make the poetry of Cavafy very relevant to the big questions about the human condition and conflicts in the 21th First Century.

A breath of fresh air, of clear thinking in these times of turmoil.

thank you, really spoke to me