Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 22, 2022

Faces of the Infinite

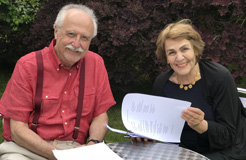

Professor Stefan Sperl talk about a new project on Neoplatonism and the poetic traditions of the Near East and Europe

Faces of the Infinite

Stefan Sperl talks about about his project on Neoplatonism and the poetic traditions of Europe and the Near East

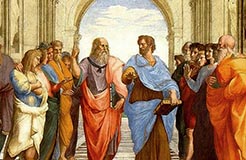

Neoplatonism, based upon the commentaries of the Egyptian philosopher Plotinus (d. 270CE), is fundamentally a mystical philosophy in which the transcendent One gives rise to the teeming diversity of our experience. The remarkable extent of its influence on the poetic traditions of the Middle East and Europe has recently been brought out by a project co-ordinated by Professor Stefan Sperl [/] of the School of African and Oriental Studies in London. This has generated both a book, Faces of the Infinite (2022) [1] and an open-access website Lyrics of Ascent [/] which presents the poetry of 65 different poets writing in ten different languages from antiquity to the present day. In this interview, Professor Sperl talks to Robin Thomson and Jane Clark about how the project came about, and its relevance to the conflicts and crises of our own time.

Robin: The website Lyrics of Ascent and the book you have edited with Yorgos Dede, Faces of the Infinite, is a wide survey – and surely also a celebration – of the influences of Neoplatonism across the Near East and into Europe, from antiquity to the present. How did the project come about?

Robin: The website Lyrics of Ascent and the book you have edited with Yorgos Dede, Faces of the Infinite, is a wide survey – and surely also a celebration – of the influences of Neoplatonism across the Near East and into Europe, from antiquity to the present. How did the project come about?

Stefan: In terms of long term interests: I studied Arabic as undergraduate and went on to do a PhD in Arabic poetry. But then I branched out and spent 10 years with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in the Middle East. This gave me knowledge of the Arab world on a practical day to day basis, and also brought me into contact with all the dislocation that produces forced migration nowadays. When I was working in the field 30 to 40 years ago it seemed a pertinent problem but it was nothing compared to what is happening now: the situation has got so much worse. I eventually returned to academia as a lecturer in Arabic but the experience I had had of dealing with migration has never left me.

My involvement with the thought of Plotinus [/] (c204–270) came about later and in several rather unexpected ways. Firstly, my late wife announced one day that she would like to make a comparison between the writings of the early Sufi mystic Harīth al-Muhāsabi [/] and the texts set by the composer Johann Sebastian Bach in his cantatas [/] on the matter of the purification of the soul. At first I thought this was quite a far-fetched comparison, but then I started reading the Bach cantata texts, which normally people don’t pay much attention to: they just listen to the music. When I started to examine where those texts come from, I was led to German mysticism, and inevitably, in turn, to Dionysius the Areopagite and his writings, which ultimately leads to Proclus and Plotinus.

As for the Arabic side: of course al-Muhāsabi’s notion of the purification of the soul comes from the Qur’an. But at the same time as the Qur’an was being composed, somebody else in the monastery of Sinai, not at all far from Mecca – John Climacus – was writing The Ladder of Divine Ascent,[2] an important monastic manual which was all about the purification of the soul. So, to cut a long story short, if you trace all these links, the common ground that you find is in the writings of Plotinus.

There was also another encounter. I was studying the proportions of the Arabic script with the Egyptian artist Ahmad Mustafa [/] and there I was confronted with geometry as an art of the highest order, in a sense forming a bridge between the divine and earthly worlds. This again turns out to be a key element in Plotinus. And, finally, the idea of producing a book was inspired by a work by Adena Tanenbaum’s, The Contemplative Soul,[3] on the Jewish Platonic prayer tradition. Seeing the pan-Mediterranean panorama that she developed, it occurred to me to create a similar work focusing on the literatures of the Mediterranean more generally, to see how this Neoplatonic tradition is reflected in the key literatures from the Christian, Muslim, and of course also in the Jewish realms.

Robin: The picture that emerges from the book is quite astonishing. You show how these ideas, beginning in the Egypt of the third century CE, spread far and wide, throughout the whole Mediterrenean region, almost like a living thing.

Stefan: Yes, the interesting thing about the propogation of Neoplatonic ideas is that it happened through a great many intermediaries. It is the mediation – the multiple mediation – of the philosophy and its amalgamation with many different intellectual traditions that makes the transmission history so fascinating. An incredible network of interrelated contacts emerges when you start to trace them all.

Jane: The 60-odd poets that you feature span a period of 1600 years and a geographical area from India to Mexico. Did you have any idea when you began of how vast the project was going to be?

Stefan: Well, it was clear from the beginning that it could only be a collective enterprise, because this goes way, way beyond the capacity of one scholar. The project actually began with a conference at SOAS in 2017, and until this happened, we weren’t sure that it would even be a viable – whether these hugely diverse literatures could really be brought into conversation with each other. But when all the scholars came together – there are 24 contributors and they normally don’t meet because they work in completely different areas or traditions – we found so many common strands that a kind of joint momentum developed. Everyone was convinced that this really was something that was hanging together, that there was a coherence there that made it worthwhile as a joint enterprise.

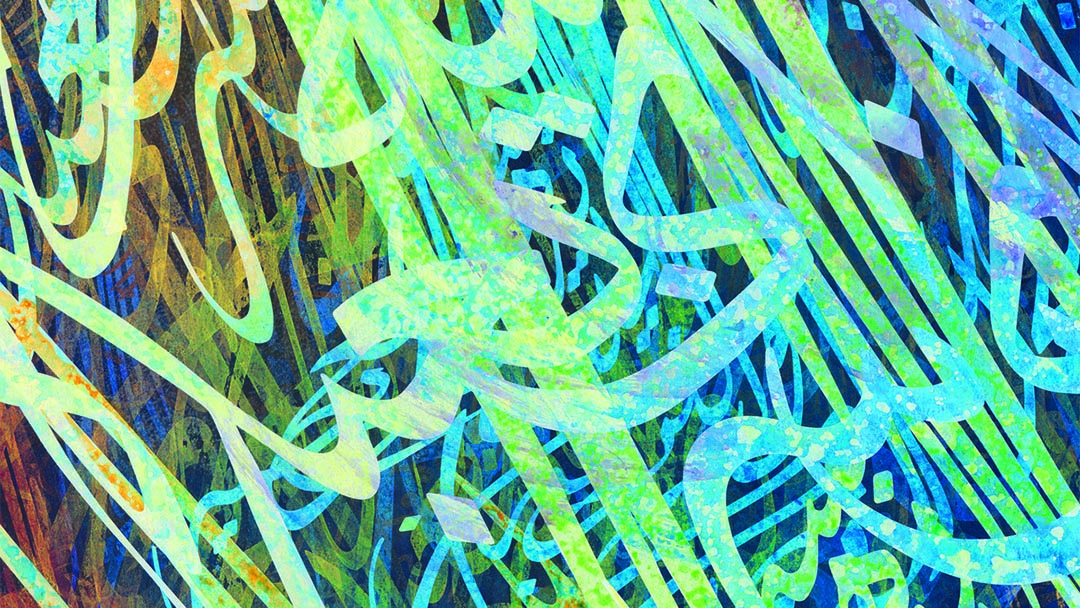

Statue commonly considered to be of Plotinus in the Ostia Antica Museo, inv. 436. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

The Vision of Neoplatonism

.

Robin: Can you sum up the basic tenets of Neoplatonism for those of us who are not so familiar with the philosophy?

Stefan: Well, it is all dependent on a certain cosmology. This is, in a sense, opposite to the modern view of the universe, in which things started with the Big Bang and the formation of matter; then this led eventually to single-cell organisms which evolved into animals and finally human beings, who are the last stage of the development of the universe. But in the Platonic tradition it’s exactly the opposite. It is also the case that everything starts with a single element, namely the One, but the first thing that emanates out of the One is consciousness – absolute consciousness.

This is so absolute that it becomes aware of itself as something known as the Universal Intellect. And as the Universal Intellect becomes aware of the One, it is filled with a sense of awe. Out of this sense of awe comes a new development, which is the Universal Soul. Then the Universal Soul becomes aware of itself and of the Intellect, and out of – if you like – another moment of awe, it produces, finally, the material world. In doing so, it ensouls the material world with the forms – the Platonic forms – that the Universal Intellect conceived in its moment of becoming conscious. So the material form of anything is nothing but a copy of an abstract form which the Universal Intellect maintains in its world of pure intellect, pure consciousness, which is invisible and immaterial.

Therefore in Neoplatonism, this material world that we can touch and see – which for us is reality – is actually the least real thing, because it is simply a transient image of eternally perfect forms. When it comes to the soul, what we carry within ourselves, within our bodily frame, is animated by an element of the Universal Soul. And this element that we carry remembers that it belonged ultimately to a far bigger entity, and in turn to the Universal Intellect, and in turn the One. So we carry within us a spark of memory of our divine origin.

This means that we are constantly searching for this, even though we are not aware of it. The reason we are always dissatisfied, always looking for something – the reason why we fall in love, why we feel incomplete – is because fundamentally we are missing this origin of whom we are deep-down still conscious. And the point of the spiritual or philosophical life is to bring this consciousness to real awareness, which ultimately enables our soul to return to that particular zone of origin from which we have, so to speak, descended. This circular vision of the soul, coming from on high, being present here in the body but longing to be returning again to this great Oneness – this is an idea that runs throughout the Neoplatonic tradition.

Jane: Beshara Magazine has published several articles recently that indicate that there is a real change of perspective going on regarding the cosmic position of consciousness, especially among physicists. It’s very likely that the idea that consciousness precedes matter is going to become standard physical theory before too long. (See for example our interviews with Bernardo Kastrup and Federico Faggin).

Stefan: Yes, I’ve read with the greatest interest and fascination that the question of whether consciousness is a late developer in the evolution of the universe or whether it has always existed is actually a point that is being debated now by scientists. So this Neoplatonic theory of consciousness is still very much a topical and unresolved question.

Jalaluddin Rumi (1207–1273) depicted at his famous meeting with his mentor Shamsoddin of Tabriz in Konya, Turkey. Depicted in Jāmi al-Siya by Muhammad Tahir Surahvadi, 17th–18th century, Topkapi Palace Museum, H1230 fol 121a. Image: via Wikimedia Commons

The Centrality of Oneness

.

Jane: Your explanation makes me wonder why we are talking about Neoplatonism rather than Platonism. Several of the things that you mention seem to me to be taken very directly from Plato – the idea of the archetypal forms: the notion that love and longing arise because we’re separated from our completion.

Stefan: That’s a very good question. Plotinus, of course, simply considered himself a commentator on Plato. He didn’t make any claims for himself as being a new start. But in a certain sense he was, and the most important reason I say this is because he developed Platonism into a system that is fundamentally focused on the notion of the One. The One achieved such prominence and centrality in his system that it really is a new focus.

This became very influential for the Near Eastern school of Platonism. And the reason I want to stress this is that all the scholars and philosophers who brought this school into being in Late Antiquity were all from the Levant – the same geographical area that produced Judaism, Christianity and Islam. It is a fundamentally Near Eastern tradition that started with Plotinus – who himself was Egyptian, of course – which reformed the original philosophy of Platonism and generated a particular, monistic vision of it. And I think that’s why the term Neoplatonism is justified, even though as a term I don’t really like it – it’s a rather ponderous word that many people can’t easily relate to.

Robin: These parallels with the monistic traditions, as well as its universality, make me think that Neoplatonism is more than just an idea. It’s almost like a revelation in its own right.

Stefan: Yes, I think you can see it like this. Chronologically, you can see it as layers – there is the Jewish layer, the Christian layer, then the Neoplatonic layer; and finally Islam, which came about in the early seventh century. The Neoplatonic layer is an additional layer of revelation that leads to the Muslim revelation. The truth of this, for me, is demonstrated by the degree to which the Qur’an actually develops key notions of the Neoplatonic tradition. The whole notion of oneness which becomes so central in the Qur’an – the ground for this was prepared in the centuries beforehand.

Robin: I’d like also to talk about the basic, common human experience of longing. We all know longing from our daily lives. Neoplatonism just seems to summarise human experience very accurately. Even in a secular sense we talk about being on a journey. As for the arts, they seem, very generally, either to be an expression of longing, or an intimation from the other side, from the Intellect, or some combination of the two.

Stefan: This links to a whole approach to beauty. How come we are receptive to beauty? And what is beauty? The way in which beauty relates to oneness – that a certain kind of oneness gives rise to beauty – also points in this very same direction. In the Neoplatonic view, beauty as such actually exists as an immaterial idea, and all beauties are images of it. We can illustrate this with the laws of physics. The laws of physics and mathematics are basically the abstract building blocks of the whole universe. Scientists keep telling us how beautiful these laws are: but they are fundamentally equations, and an equation is all about a balance between different things, as the word indicates, and hence about unity.

The Power of Poetic Expression

.

Jane: You have spoken about the prevalence of this tradition in all areas of culture, but in your project you have focused on poetry. Why did you choose this rather than, say, architecture, or any of the other arts? Or all of them?

Stefan: The simplest answer is that poetry has been my subject from the beginning. But as you say, the ideas are just as relevant for the other arts, and for music. The reason why I think poetry is a suitable medium for this enquiry is because Neoplatonism is essentially not just a speculative philosophy but an experiential one. The point that Plotinus always makes is that the rational mind is simply a stepping stone towards experiencing something that is impossible to describe in rational terms – the kind of experience which goes beyond the realm that pure reason can capture.

Poetry expresses the emotional state that arises when certain insights are achieved. And that’s precisely why it can be a privileged medium to convey the conclusions – the experiential conclusions – of the Neoplatonic vision of reality. The Islamic mystic/philosopher Ibn ‘Arabi is a good example of this. His writings usually take the form of metaphysical exposition, but he breaks into poetry when something happens that his prosaic intellectual exploration can’t convey. Poetry is an experience that brings emotion together, whereas rational analysis takes things apart. What makes something poetic is, very simply, that it always points beyond itself; it says something, of course, but it also hints at something beyond what it is trying to say.

Robin: Could it also be that in poetry, particularly because of its use of image, we’re leaving the literal and approaching the intelligible, the Intellect?

Stefan: Sure. That’s also why the Qur‘an is an incredibly poetic text. It’s full of poetic imagery for that very reason. But to go back to what Jane said, while this book is focused on poetry, the issue of architecture, music, the visual arts, is so relevant that there could be another book dealing more specifically with those artforms from this perspective.

W. B. Yeats (1865–1939) with members of the Bloomsbury group – Edward Sackville-West; Siegfried Sasson; Julian Vinogradoff; Philip Morrel and Ethel Sands – at Garsington, UK, in 1926. Photograph: Lady Ottoline Morrell © National Portrait Gallery, London

Jane: We tend to think of Neoplatonism as something in the past but the book includes quite a number of modern poets: ‘modern’ both in the sense of modern era like Wordsworth and Shelley and W.B. Yeats, and in the sense of contemporary living artists.

Stefan: Neoplatonism is relevant to modern poets first of all simply because every poet always engages in some way with his or her tradition. So modern writers inevitably engage with what was Neoplatonic in their own tradition. So in the Arabic, Persian and Turkish poetry discussed in the book, we find people looking particularly at the Sufi past, at Sufi poetry, asking: how does this message make sense today? The old images are still there, but they are placed into a new context, and that context is basically a context of dislocation. With all the modern poets, the harmonious vision of the universe conveyed by their tradition is broken.

Nevertheless, the search for this transcendent target of the soul is as vibrant as ever. So where is it to be found? And that’s where something becomes evident that Mehmet Kalpaklı and Neslihan Demirkol, the authors of the modern Turkish paper in Faces of the Infinite, call ‘secular mysticism’. So a number of the modern poets locate the transcendent world in the phenomenon of nature. One example is the Italian poet Eugenio Montale [/], who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1975. When Montale engages with the past, Dante is the big figure: that’s where he encounters, so to speak, his Neoplatonic tradition. But when it comes to finding the divine presence, there’s an amazing poem called I Limoni (‘The Lemons’), in which at the end he discovers the memory of something ineffable just in the smell of lemons. Here is the final stanza:

But the illusion is lost and time brings us back

to the raucous cities where blue appears

only in pieces, high up, between the tiles.

Rain tires the earth, later; the winter’s

slowness weighs on houses,

the light grows mean—mean the spirit.

When one day from an ill shut gate

amidst the courtyard trees

to us there appears the yellow of lemons;

and the ice in the heart is undone

and we’re showered in the breast

with the songs

from gold trumpets of the sun.[4]

And then there is a wonderful poem, or rather ‘profession of faith’, by the Iranian poet Sohrab Sepehri [/]. In it, he describes his prayer, and this also is directed to the manifestations of nature. Rather than in a mosque or at the Ka’ba, he finds signs of God’s existence in the natural world. This is of course completely Qur’anic, because within the Islamic tradition all manifestations of nature are understood to be signs pointing towards the ultimate Oneness from which everything has come. But Sepehri deliberately steps away from established religion and finds a kind of spirituality that is orientated towards what I call the ‘significatory power’ of the natural world.

I am a Muslim

pray facing a red rose

over a jetting fountain

and press my forehead against a shaft of light,

sensing that the whole plain is a prayer rug.

I do my ablutions along with pulsating lattices,

the moon flows in my prayer, as does an apparition

and as does a rock through it.

And the particles of my prayer glow and turn luminous.

I pray after the wind has made its call from the minaret that is the cypress

I pray after the grass has uttered its ‘God is glorious’ chant,

after the billowing of the surge.

My sacred sanctuary stands at the edge of the sea

moves through the acacias

flows from garden to garden, from one city to the next,

much like the breeze.

My Black Stone is the glowing of a little flower-bed.[5]

There are also poets like the Spanish writer Valente [/], and Muhammad Afifi Matar [/] from Egypt, who have read Plotinus in the original and engaged directly with the Neoplatonic tradition, bringing it to fruition in their own works. So there are various ways in which this tradition survives. What is common to them all in some way or other is the confrontation with a thoroughly undesirable political reality: fascism, in the case of Montale and Valente; and in Turkey a kind of schizophrenia, modern Turkey being half Islamic and half secular. So there is an identity crisis that is expressed in all these modern writers.

Jane: How do you feel that they resolve this?

Stefan: I would say that they find their way out of it by seeking to revive certain aspects of the vision of the past and realising them in new ways, like, as I said, in the manifestation of nature. As for Valente, well, Claudio Rodríguez Fer, who wrote the chapter on his work, called it ‘The Eroticism of the Infinite’.[6] Because in his love poetry he makes the experience of physical love transubstantiated into a mystical experience. The bodily, the physical, the natural world, is divinised in his writings, because the great Unknown, so to speak, of the Neoplatonic hierarchy has disappeared. This unknown is replaced here by the divinisation of the material.

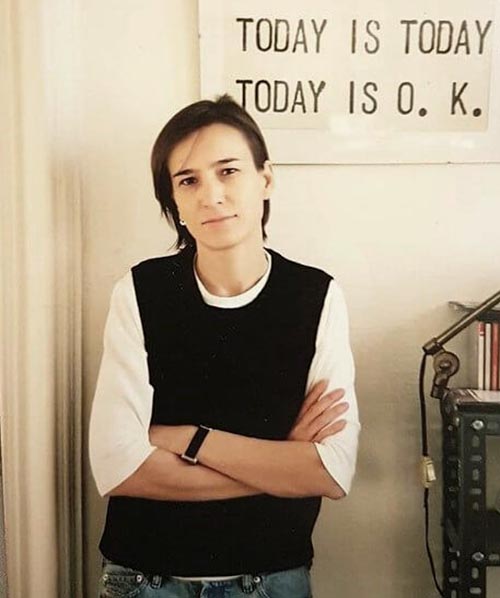

Sohrab Sepehri (1928–1980), who was also known as an accomplished painter. Image: Wikiart

Oneness by Inclusion

.

Robin: There is something in all of this that suggests that Neoplatonism has direct practical application today, going beyond what we classify as the arts. For example, your introduction to Faces of the Infinite opens with reference to the intolerance and hate that occur frequently around the world. Would you say that this kind of approach can help us in dealing with the immediate problems we face?

Stefan: My motivation behind the book was exactly this. To explain, let me go back to the notion of the One and what it means. You see, acts of hate, any kind of fascism or extremism or fanaticism – all of them are concerned with the notion of the One. What the fascists want is oneness in order to generate a hegemonic society, but it is oneness based on exclusion. The clearest example of this is the principal slogan of the German Nazi party: Ein Reich, ein Volk, ein Führer (‘One Empire, one people, one leader’). It’s all about ‘one’.

But if you look at this from a Neoplatonic perspective, it is clear that they are making a catastrophic mistake. Because what Plotinus teaches is that the One, in absolute terms, does not exist in this world. Every oneness in this world is actually composite. Even the atom is composite. And if a ‘oneness’ in this world is beautiful, it is because different parts have come together to create a harmonious whole. So Neoplatonism is all about oneness by inclusion, whereas these extreme political movements are all about oneness by exclusion. And exclusion creates conflict, separation, destabilisation, disintegration and so on, and all the strife that arises out of this. So, from a Neoplatonist perspective, those people who are after oneness by exclusion have no idea that the real image of the ultimate One in this world can only be a oneness by inclusion.

Here I see really the ethical, moral impetus of Neoplatonism, to bring about in our lives, in ourselves and in our society a oneness by inclusion with all that this means – with all the concessions, the struggles, the dialogue and mutual understanding that is required for it. Each human being is a manifestation of the One and the One is present in every part.

Robin: So by ‘inclusion’ what you are implying is that there is a real place for difference and diversity?

Stefan: Yes; this is very important. Because the ultimate reality is essentially undefinable, there is never only one answer to anything, and nothing has only one meaning. That’s one of the funny consequences of this philosophy: the more you focus on the One in its transcendence, the more you become aware of the multiplicity of meaning in its immanence. There’s a strange dialectic between the two. This why the Neoplatonic vision is open to difference, and why diversity is an inevitable consequence of the complete transcendence of the One. Because the One as such is unreachable.

The contemporary Turkish poet, Birhan Keskin (b. 1963), one of several living poets featured in Faces of Infinity. Image: https://www.soylentidergi.com/filtresiz-sair-birhan-keskin/

Oneness and Collectivity

.

Robin: With regard to our plight in the present time, how would taking a Neoplatonic perspective see what seems to be the destruction of nature – the very nature that the poets deify – and our impending climate collapse?

Stefan: Well, Plato described the world as a comprehensive living being. This means that everything in the natural world depends on everything else. So using nature simply for the sake of consumption without paying attention to its wellbeing, or seeing how every part of nature plays a role in the whole, is evidently for us a great risk, as we can see all around us.

Plotinus also develops the notion that everything is ‘ensouled’ – even stones; everything is part of the great unity, and therefore nature in a way is holy and has to be cared for in this particular way. Nothing is ruined or exploited without due regard to what effects consumption may cause. So the ethical imperative for the conservation of the natural world is part of the Neoplatonic message – there’s no question about that. Like the Gaia hypothesis [/]; the Gaia hypothesis is expressed almost literally by Plotinus.

Robin: You have mentioned the sense of dislocation which many people in the Middle East are experiencing. But it seems to me that generally in our age, the sense of exile and separation – as underpins the soul’s experience in Neoplatonism – feels greater now than ever.

Stefan: Yes. It’s as though the Universal Soul – which is inspired by the longing of the One and is the source of our own longing: you can liken it perhaps to the collective unconscious in Jung – is searching, collectively, for this ideal of the One by falling in on itself, restricting itself. What I see happening the world over is that we are going through a period of collective illness of the Universal Soul.

But I don’t think Plotinus would have been surprised by what is happening, because he says that as long as we live in a world where material concerns are paramount, it is impossible for us to disenfranchise ourselves, liberate ourselves, from these kinds of strictures. And it’s ultimately the task of every individual to achieve, to seek, their own individual path towards enlightenment. It’s only the individual, on their own, that can do this. Collectivities basically cannot achieve it. That is what I read in his view – so he is, in a sense, pessimistic as far as collectivities are concerned, but optimistic for the individual.

Jane: I am surprised to learn that there is no collective dimension to the spiritual path in Neoplatonism. In Sufism, which you associate with the tradition, it is actually a very strong aspect of the spiritual journey that we make it together.

Stefan: This is an aspect developed specifically within Sufism. The Sufi tradition collectivises the journey in the form of brotherhoods and so on, but in Plotinus that’s not the case. For him, it’s an individual matter. You don’t need to belong to a church or a club, there’s no priest, and nobody above you. Just you and It. Nothing else. This makes it in a sense anti-authoritarian, liberating – universally applicable. There’s just you and Up There.

Robin: Which makes it an ideal philosophy for a society where individualism has come to prevail, don’t you think? Maybe ironically! Thank you Stefan for talking to us and sharing this large-spirited project.

Faces of the Infinite is available from Oxford University Press [/], and also, of course, Amazon.

Faces of the Infinite is available from Oxford University Press [/], and also, of course, Amazon.

The Lyrics of Ascent website is an open-access resource which gives information about the different traditions covered by the project and the 65 featured poets, plus versions of the poems in both their source language and English translation. This is an ongoing project to which new material is periodically added.

Image Sources (click to close)

Inset: Professor Stefan Sperl

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] STEFAN SPERL and YORGOS DEDE, Faces of the Infinite: Neoplatonism and Poetry at the Confluence of Africa, Asia and Europe (British Academy, 2022).

[2] St JOHN CLIMACUS, The Ladder of Divine Ascent (lul.com, 2021).

[3] ADENA TANENBAUM, The Contemplative Soul: Hebrew Poetry and Philosophical Theory in Medieval Spain (Brill, 2002, ISBN 9004120912).

[4] EUGENIO MONTALE, Extract from I Limoni [/] in PETER ROBINSON: ‘An Equivocal Echo: Eugenio Montale’ in STEFAN SSPERL and YORGOS DEDE, Faces of the Infinite, p. 362

[5] SOHRĀB SEPEHRĪ, I am a Muslim [/] in AHMAD KARIMI-HAKKAK: ‘Shards of Infinitude: Neoplatonist Relics in Modern Persian Poetry’ in STEFAN SPERL and YORGOS DEDE, Faces of the Infinite, p. 426

[6] See CLAUDIO RODRIGUEZ FER, ‘Eroticism of the Infinite: Neoplatonism, Kabbalism and Sufism in the work of José Ángel Valente’ in STEFAN SPERL and YORGOS DEDE, Faces of the Infinite, p. 373

Move your computer mouse over the banner image in order to enlarge

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Bring Back Metaphysics!

Scientist and writer Colin Tudge makes a plea for us to return to what he calls ‘The Art of the Unknowable’

World Literature Decentered

Ian Almond talks with Jane Clark about a more inclusive approach to comparative literature, and the cultural traditions of Turkey, Mexico and Bengal

Bewildered by Love and Longing

Michael Sells and Simone Fattal talk about a new translation of Ibn ‘Arabi’s famous cycle of love poems Translation of Desires

Dante, Erotic Love and the Path to God

Mark Vernon explores a pivotal moment of transformation in the Divine Comedy

READERS’ COMMENTS

Thank you for this interesting discussion with Professor Sperl and his on-going work relating to Plotinus and the Neoplatonic tradition, to which I would like to offer some thoughts. Undoubtedly, the Neoplatonic tradition has been a huge spiritual influence in Judaism, Christianity and Islam, nurtured, according to the article, by scholars and philosophers from the Levant, even though Plotinus himself was Egyptian. I was very struck, though, by certain remarks, particularly that modern poets ‘locate the transcendent world in the phenomenon of nature’ and their ‘divinization of the material’. As, to my mind at least, these have far more the ring of that much-derided art of alchemy than Neoplatonism, an alchemical aura beautifully captured in the lines quoted from the poem ‘The Lemons’. Indeed, Plotinus’s teachings quoted in the article -that every oneness is ‘composite’, and that if a ‘oneness in this world is beautiful, it is because different parts have come together to create a harmonious whole’ – could equally apply to the alchemy practised already by Graeco-Egyptian alchemists, and continuing right through into Western alchemy. For it is a central alchemical aim to turn a ‘composite’ substance into flowing, harmonious unity, ‘to distil the eternal from the transient’, to use Baudelaire’s phrase, as I have tried to set out in my book ‘Hathor’s Alchemy: The Ancient Egyptian Roots of the Hermetic Art’ (2019) and in an article in ‘JMIAS 71 (2022)’ and ‘JMIAS 72 (forthcoming 2023).

Alchemy, too, is a formative tradition, with which mystics and poets have engaged. One need but mention Rumi and Ibn Arabi, or William Blake who was steeped in alchemy, as were George Herbert, Goethe and the German mystic Jacob Boehme. Shakespeare has innumerable references to alchemy. The list could go on. However, the roots of this alchemy are in Egypt, not the Levant; and there are also important differences from Neoplatonism. Firstly, the Feminine is essential to the alchemical work of creating balance and harmony. Secondly, alchemists see the material world, not as ‘the least real thing, because it is simply a transient image of eternally perfect forms’, but rather as inherently sacred, enclosing an eternal ‘essence’, which they seek to bring into manifestation by purifying the ‘mixed’ and returning it to ‘Oneness’. The goal is not to leave the material world behind, though, but rather ‘to make the hidden manifest’, in other words a ‘divinizing’ work revealing the Philosophers’ Stone; and as a revelatory art, alchemy offers a spiritual path, which, with its reverence for earthly life, can speak to modern-day seekers, artists and poets in Gaia’s suffering world.