Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 22, 2022

Participating in the Divine Playfulness

Hina Khalid explores the theological aesthetics of Rabindranath Tagore

Participating in the Divine Playfulness

Hina Khalid explores the Theological Aesthetics of Rabindranath Tagore

The question of how art relates to truth, and how our finite human creativity might represent something of the non-finite creativity of the divine, has long occupied theologians and poets of various religious traditions. There are a myriad ways that human creativity has been configured as a dynamic site of religious reflection – from outlining the intricate, spiritually-saturated relation between outward ‘form’ and inner ‘meaning’ in writing a poem, composing a song, or sketching a landscape, to meditatively pondering on the source of such artistic inspiration. In this short piece, I will bring two distinctive conceptions of the arts – one informed by the Hindu worldview of Rabindranath Tagore and the other shaped by the Roman Catholic tradition as expressed by the German philosopher Josef Pieper – into dialogue with another, to explore how our creativity constitutes a colourful thread which interlaces the material and the spiritual. I suggest that such a cross-theological enquiry into the spiritual import of the arts affords us fertile ground in which to sow new seeds of inter-faith conversation and collaborative creativity.

The question of how art relates to truth, and how our finite human creativity might represent something of the non-finite creativity of the divine, has long occupied theologians and poets of various religious traditions. There are a myriad ways that human creativity has been configured as a dynamic site of religious reflection – from outlining the intricate, spiritually-saturated relation between outward ‘form’ and inner ‘meaning’ in writing a poem, composing a song, or sketching a landscape, to meditatively pondering on the source of such artistic inspiration. In this short piece, I will bring two distinctive conceptions of the arts – one informed by the Hindu worldview of Rabindranath Tagore and the other shaped by the Roman Catholic tradition as expressed by the German philosopher Josef Pieper – into dialogue with another, to explore how our creativity constitutes a colourful thread which interlaces the material and the spiritual. I suggest that such a cross-theological enquiry into the spiritual import of the arts affords us fertile ground in which to sow new seeds of inter-faith conversation and collaborative creativity.

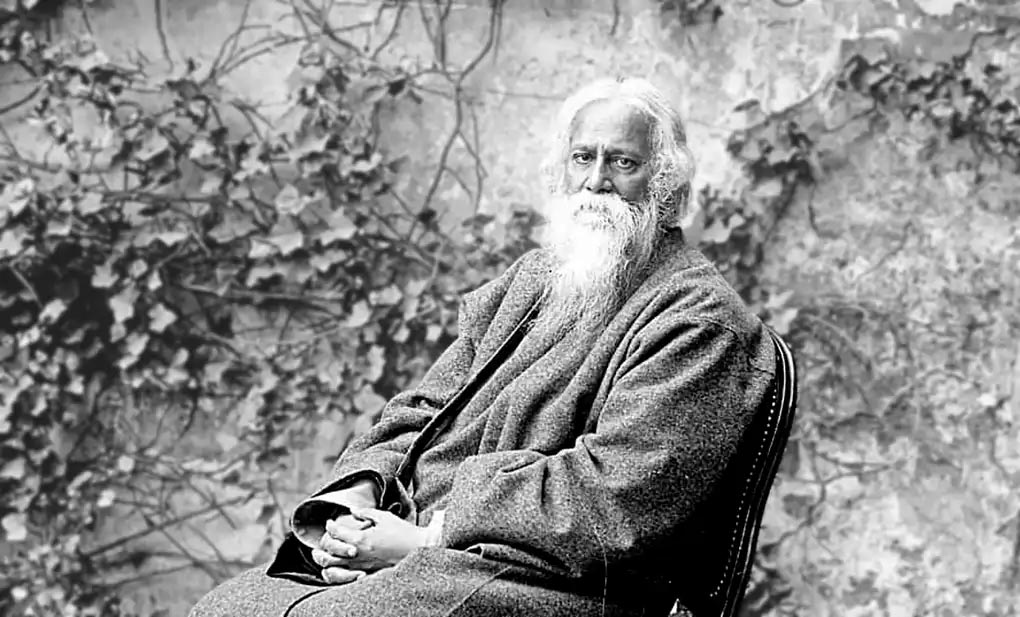

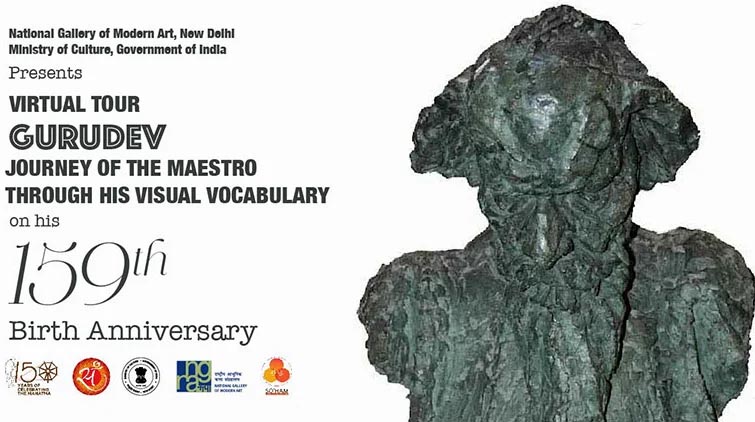

Our first dialogue partner is the celebrated writer and artist Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941). Tagore is perhaps the most famous Bengali poet of the modern age, whose tender verses continue to resound through the soft breezes of Bengal’s villages. Primarily celebrated as a poet who became popular in the West after receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913 (he was the first non-European to win it), he was also a philosophical thinker, a playwright, an author of short stories, the composer of around 2,200 songs, and even a painter towards the end of his life.

An important, lifelong concern of Tagore’s was the relationship between the East and the West – more specifically, how the particularities of one’s own spiritual and cultural tradition could be preserved whilst sustaining an intellectual hospitality to the socio-religious other. To promote this vision of internationalism, he established in 1921, a university, which he envisaged as an abode of peace where ‘the whole world might meet in a single nest’.[1]

This image of a nest quite beautifully segues into our discussion of Tagore’s conception of the divine–world relation – for Tagore presents the world as intimately ‘nestled’ in the womb of God, enfolded in the divine embrace, and ensconced in the divine bliss. Ever-enveloped by the sacred, the finite world stands as a shimmering sign of the inexhaustible infinite.

Rabindranath Tagore, “Dancing Woman”. Painting in the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, India

The World Sung into Being

.

At the heart of Tagore’s cosmology is the notion that the world is joyously sung into being. This creative sonic effusion is not a singular burst of divine activity but is continually resounding through the cosmos in ever-new forms. The world is made up of a dynamically changing and perpetually enchanting stream of notes, each of which reveals what Tagore called the cosmic harmony (sāmañjasya) of the finite and the infinite.[2] Unlike other forms of art where the final artwork gains an independent existence – once a painting, for instance, is completed, the painter withdraws her loving touch – the melodies that emanate from this singer cannot be disjoined from their creative source.[3] The world-song is re-enlivened with each divine exhalation, and the divine voice pulsates through it at every moment. In Tagore’s words:

The universe is not a mere echo, reverberating from sky to sky, like a homeless wanderer – the echo of an old song sung once for all… and then left orphaned. Every moment it comes from the heart of the master, it is breathed in his breath.[4]

This notion of creation as God’s song represents Tagore’s recalibration of the crucial Hindu idiom of līlā. A multi-faceted Sanskrit term with meanings such as ‘sport’, ‘play’, ‘charm’, ‘beauty’, and others, līlā refers to the idea in Hindu cosmologies that God is a free artist who produces and sustains the world through a spontaneously ‘excessive’ overflow of the divine bliss (ānanda). This divine creativity is not necessitated by any external imperative, for this would suggest that God lacks something that the world fulfils. Echoing these theological templates of līlā, Tagore writes:

God’s creation has not its source in any necessity; it comes from his fullness of joy; it is his love that creates, therefore in creation is his own revealment.[5]

In short, as a sacred symphony that God freely sings into being, creation flows from, and ever-newly unfolds, the divine abundance. Somewhat paradoxically, Tagore presents this joyful self-revelation as God’s renunciation, or sacrifice, of Himself in and to the finite world.[6] For Tagore, these seemingly opposed ideals of abundance and renunciation are harmonised through the cosmic force of love. Outlining the nature of God’s creative love (prem), Tagore affirms that the plenitude of love is inseparably connected to the austerity of sacrifice (tyāg):[7] this is because without love there is no true sacrifice, just as without sacrifice there is no true love. Since God is the true form of love, God is also the paradigmatic sacrificer – indeed, it is precisely because God is never beholden to necessity that He is continually ‘giving Himself’ to the finite world in joy.[8] In God’s inexhaustible plenitude, to give is to be, so that renunciation is abundance, and this dynamic of self-recovery through self-offering represents the archetype for our own activities in the world. In other words, the Tagorean maxim seems to be this: I give, therefore I am.

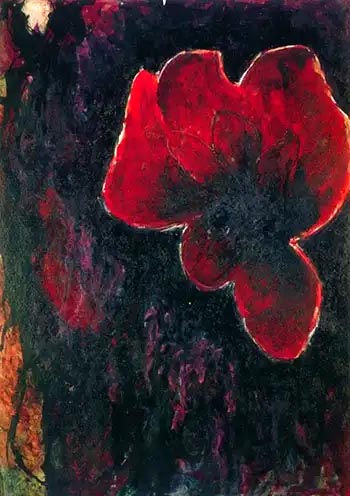

Rabindranath Tagore, “Landscape” (1937). Image via Wikimedia Commons

The Tender Call of Love

.

God is thus perpetually renouncing Himself in and to the world in the cosmic līlā, and it is in and through the freedom of the human personality that this cosmic gift becomes known – and is responded to – as gift. Indeed, that this finite world is a gift is realised only by the personal self who is capable of receiving it as such – for a gift is not a mechanical transaction but an intimate offering of love, made by the ‘soul unto the soul’.[9] From the heart of creation arises a perpetual call unto the human person, questioning her thus:

[…] friend, have you seen me? Do you love me? – not as one who provides you with foods and fruits, not as one whose laws you have found out, but as one who is personal, individual?[10]

The gift of God that is the world issues a tender call of love, and without a loving response to this call, the gift remains unrealised. Love constitutes a fitting response, Tagore emphasises, precisely because a response is only true if it is freely offered, and love is quintessentially that which cannot be coerced. The human–world relation thus represents a perpetually spiralling circuit of self-constitution and self-donation: the world, which is God’s joyous self-offering, gives itself to us, and we in turn are called to give our love to it. When we do so, we become more firmly embedded in the ongoing spirals of divine–human interplay.

One of the most enchanting notes of the world’s polyphonic ‘love-call’ is that of beauty,[11] which silently streams through the spring flowers and the serene night sky. Tagore presents worldly beauty as a constantly streaming song and even as God’s ‘love letter’ to us, which many of us have – unfortunately – not yet read.[12] As a result, the blissful encounter of love to which we are called remains unrealised. God could have set forth a regal display of the divine power, Tagore writes, which would force us to turn to Him, but instead He seeks to gently woo us through the innumerable beauties of the world – the delicate dreaminess of dawn and the soft serenity of sunset. Indeed, God takes the ‘risk’ that these unfoldings of His beauty will be ignored by us and even that we will reject this beauty as ‘futile’. But still, He will not compel us in any way.[13]

Outlining this tender abundance, Tagore writes that whilst we must acknowledge and align ourselves with the fact that the sunrise heralds a new day – and pursue our daily work accordingly – we are not under any compulsion to discern the dawn as ‘beautiful and supremely peaceful’.[14] Our loving attentiveness to its beauty is thus entirely free, but this is itself a freedom to which we are, in a higher sense, bound – for it is only in our free submission to beauty’s call that we inhabit the infinite truth of human life and come to know that this existence is, in fact, ‘a birth of joy’.[15]

One type of loving response to this divine call of beauty is crystallised for Tagore in the vocation of the artist. Tagore presents art as a joyful meeting of the divine and the human, which recapitulates in and through time the love-infused līlā of the primordial divine artist. Like God’s cosmic līlā, art has its origins in the realm of ‘excess’, because we create art not as a means to an end but for freely delighting in the beauty of the world. In other words, when we renounce utilitarian or instrumentalist imperatives in and through artistic creation, revealing the ‘wealth’ of our inner life, we reflect the God who ‘takes joy in productions that are unnecessary to him’.[16] The artist offers herself and her art to God in perpetual iterations of re-turning, and utters in response to the world’s call:

Yes, I have seen you, I have loved and known you, – not that I have any need of you, not that I have taken you and used your laws for my own purposes of power… I see you, where you are what I am.[17]

The artist thus realises the world not in the arid modality of static objecthood but in the surplus of participatory love. Ordinarily, Tagore notes, we do not give to the world of our true creative abundance, for the world remains dimmed for us under the veil of utility. Like the passenger on the train who is aware of the outside world but for whom the immediate carriage is more ‘real’, we typically only see the things that serve our purpose. Much of our world thus ‘passes by us, a caravan of shadows’.[18] In creating art, however, we are able to lift the blinkers that ordinarily structure our ways of seeing, and direct our gaze toward the transcendent truth of things. It is not only, therefore, that the artist sees more, but that she also sees more deeply, much like a child who, Tagore writes, does not know its mother’s name or any other ‘facts’ about her, but knows her truly in its intimate love for her.[19] In one of his poems he writes:

What divine drink would you have, my God, from this overflowing cup of my life?

My poet, is it your delight to see your creation through my eyes and to stand at the portals of my ears silently to listen to your own eternal harmony?

Your world is weaving words in my mind and your joy is adding music to them.

You give yourself to me in love and then feel your own entire sweetness in me.[20]

Rabindranath Tagore, “Woman with Flower”. Painting in the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, India

Seeing Through Love: Josef Pieper

.

There are some quite beautiful and fertile resonances between this Tagorean conception of the artist’s vision and the notion of artistic perception put forward by the German Catholic philosopher, Josef Pieper (1904–1997). Pieper was a professor of philosophical anthropology at the University of Münster, and is best known for his work on Thomas Aquinas, which played a significant role in the resurgence of interest in the great medieval thinker in the mid-20th century. I will comment mostly on his wonderful work, Only the Lover Sings: Art and Contemplation, in which he sets forth a meditative account of what it means to truly see the world as infused with a spiritual depth.

Evoking Tagore’s elaboration of the ‘shadows’ that obscure our vision of reality, Pieper urges us to see things as they truly are, without the manifold veils of disillusionment, greed or boredom that tether us to our self-referential vistas. In this deeper mode of seeing lies the creative origin of true art: when the artistic impulse is nourished in a self-transcending, contemplative attention to the inner richness of things, its outward form bears the indelible imprint of the sacred. Thus, Pieper writes:

Long before a creation is completed, the artist has gained for himself another and more intimate achievement: a deeper and more receptive vision, a more intense awareness… a more patient openness for all things quiet and inconspicuous, an eye for things previously overlooked. In short: the artist will be able to perceive with new eyes the abundant wealth of all visible reality, and, thus challenged, additionally acquires the inner capacity to absorb into his mind such an exceedingly rich harvest. The capacity to see increases.[21]

Endowed with this vision into the plenitude of finite reality, the artist sees more truly, and this is, in short, because she sees with the illuminative lens of love. To see through love is not to veer away from truth but to enter more fully into it, for love, in the worldviews of both Tagore and Pieper, is not a fleeting sentiment or subjective fancy but constitutes the ontological heartbeat of all created reality. As Tagore affirms, love ‘radiantly reveals the reality of its objects’,[22] and, in Pieper’s formulation, the contemplative gaze is only truly itself when it is ‘guided by love… for a new dimension of ‘seeing’ is opened up by love alone’.[23]

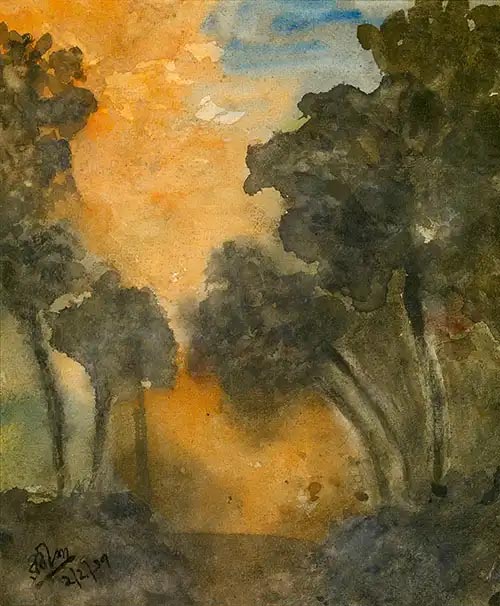

This attentive attunement to the truth of things marks, crucially, not a feat of mastery, as though the artist has domesticated the object in her imaginative purview, but heralds an opening into mystery, where the object, and thus the artwork that bears witness to it, tantalisingly resists final capture. What we encounter in art is not an object of the ordinary kind, which we can hurriedly assimilate into our mundane classificatory schemes, but an ineffable horizon of meaning which recedes as it reveals, eludes as it illuminates, and entangles as it enchants. In Pieper’s words:

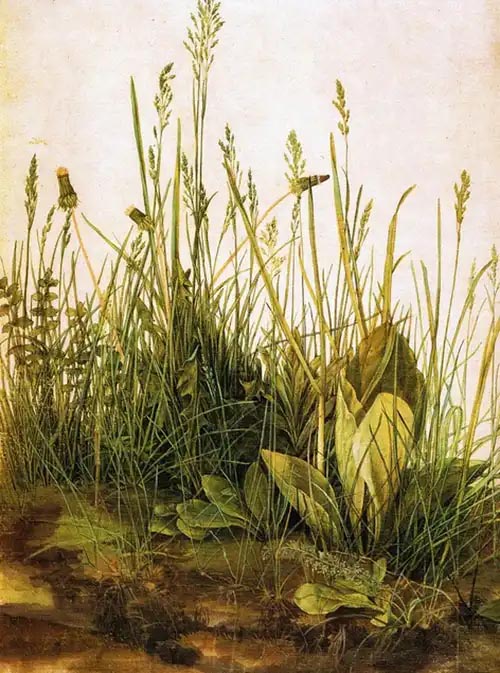

[…] what do we really perceive when we look at, say, Durer’s ‘Detail of a Meadow’? It is obviously not the blades of grass, which we can observe, even more realistically, also in nature or in a photograph. It is not the blades of grass, not ‘this particular object’ at all… [and] what about songs? […] Of course we hear the words [of the song]! – and yet, provided we witness authentic and significant music and provided we listen in the proper manner, we invariably perceive an additional, most intimate, meaning that would be absent from the words alone.[24]

Tagore echoes this observation of the ‘object-lessness’ of art. Commenting on a poem particularly beloved to him, he writes:

[…] it [the poem] has its grammar, its vocabulary; when we divide them part by part and try to torture out a confession from them, the poem, which is one, departs like the gentle wind, silently, invisibly. No one knows how it exceeds all its parts, transcends all its laws, and communicates with the person. The significance which is in unity is an eternal wonder.[25]

In Tagore’s theological vocabulary, this ungraspable ‘unity’ refers to the atman, the Sanskrit term for the immutable spiritual self which abides within, and yet transcends, all individual beings. Tagore defines the atman as that ‘inner perfection that permeates and exceeds its contents, like the beauty in a lotus which is ineffably more than all the constituents of the flower’.[26] The lotus’s beauty unifies and illumines its individual parts but is not itself one part among those parts, much like, to borrow another one of Tagore’s examples, the melodious whole of a sonata is inseparable from its constituent elements but is not reducible to them.[27]

Albrecht Dürer, “Great Piece of Turf” (1503). Image via Wikimedia Commons

Offering Back to the One

.

In Tagore’s aesthetic vision, then, the artist transcends her individual self to inhabit the world in attentive love, and her art, nourished in ‘self-forgetful joy’,[28] in turn sets forth the possibility of self-transcendence for others. In this way, Tagore affirms, a true work of art is ‘always speaking’,[29] calling the recipient out of themselves towards the other. The artist gazes on the world through the eyes of the heart, and through this intensive witnessing of reality, sees beyond the surface of things to inhabit, and to illumine, the silent fecundity of created being. Through her creative offerings, the artist responds to, realises and reflects the divine, and in this way, art approximates something akin to worship. The worshipper, like the artist, suspends her quotidian self-orientation to give herself to the God who is perpetually giving Himself to the world.

Elaborating this mode of self-offering, we repeatedly find across Tagore’s poetry the insistence that, through his creative efflorescence, he is only returning to God that which God has already gifted him. Just as the spring flowers blossom in God’s time and not ours, Tagore’s poems too have their ultimate root not in anything of his making but in the One who implants in all beings their particular perfections. This joyous [of] cycle of gaining and giving is, for Tagore, the archetype of all our finite activities: to harmonise the tunes of our individual wills with the divine will, we must continually dedicate ourselves and our works to the divine singer, in whose breath we live, move, and have our being. On this note of the cosmic circuitry of receiving and returning, I will let the great C.S. Lewis, who echoes here the musical motifs of Tagore, have the last word:

There is of course a sense in which no one can give to God anything which is not already His – and if it is already His, what have you given? But since it is only too obvious that we can withhold ourselves, our wills and hearts from God, we can, in that sense, also give them. What is His by right and would not exist for a moment if it ceased to be His (as the song is the singer’s), He has nevertheless made ours in such a way that we can freely offer it back to Him.[30]

To see more of Tagore’s paintings held at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Delhi, click here [/]

Hina Khalid is a PhD student at the Faculty of Divinity, University of Cambridge. She is working on a comparative study of the theology and poetry of Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938) and Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941). She is particularity interested in the possibilities of comparative theology across Islamic and Indic traditions, and in the ways that shared devotional idioms have formed in and across the Indian subcontinent. Her previous publications have centred on a range of topics, including issues of embodiment, gender, and spirituality across the Christian, Islamic, and Indic worldviews

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Rabindranath Tagore.

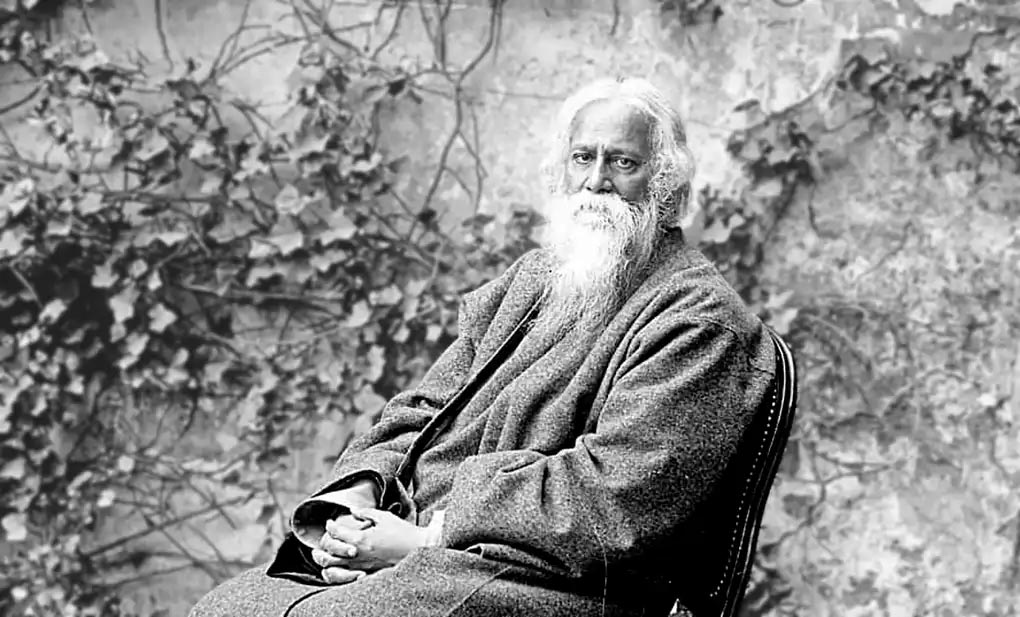

Inset: Painting by Rabindranath Tagore.

Other Sources (click to open)

[2] RABINDRANATH TAGORE, Sāmañjasya, Rabīndra Racanābalī [RR], Volume 13 (Calcutta: Visva-Bharati, 1965-1971).

[3] TAGORE, Sadhana: The Realization of Life (Radford: Wilder Publications, 2008), p. 67.

[4] TAGORE, Sadhana, p. 44.

[5] TAGORE, Sadhana, p. 39.

[6] TAGORE, Prem, RR, Vol 13.

[7] TAGORE, Prem, RR, Vol 13.

[8] TAGORE, Personality (Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2002), p. 67.

[9] TAGORE, Personality, p. 76.

[10] TAGORE, Personality, p. 22.

[11] TAGORE, The Religion of Man (London: Unwin Paperbacks, 1931), p. 87.

[12] TAGORE, Sadhana, p. 49.

[13] TAGORE, Saundarya, RR, Vol 13.

[14] TAGORE, Saundarya, RR, Vol 13.

[15] TAGORE, Saundarya, RR, Vol 13.

[16] TAGORE, ‘The Religion of an Artist’, in Contemporary Indian Philosophy, ed. S. Radhakrishnan and J.H. Muirhead (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1936), p. 34.

[17] TAGORE, Personality, p. 22.

[18] TAGORE, ‘The Religion of an Artist’, p. 35.

[19] TAGORE, Personality, p. 104.

[20] TAGORE, Gitanjali, 65

[21] JOSEF PIEPER, Only the Lover Sings: Art and Contemplation (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1990), p. 36.

[22] TAGORE, ‘The Religion of an Artist’, p. 35.

[23] PIEPER, Only the Lover Sings, p. 74.

[24] PIEPER, Only the Lover Sings, p. 41.

[25] TAGORE, ‘The Religion of an Artist’, p. 43.

[26] TAGORE, The Religion of Man, p. 40.

[27] TAGORE, Personality, p. 57.

[28] SARVEPALLI RADHAKRISHNAN, The Philosophy of Rabindranath Tagore (Delhi: Nyogi Books, 2015), p. 86.

[29] TAGORE, ‘The Religion of an Artist’, p. 38.

[30] C.S. LEWIS, The Four Loves (New York: Harcourt, 1960), pp.177–78.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

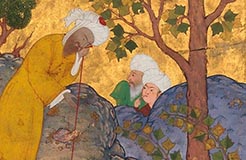

Exploring the Power of Love in ‘Attar’s Conference of the Birds

Kenneth Avery explores the famous story of Shaykh San‘an and its message of love and friendship across religious boundaries

Beauty Happens

Ornithologist Richard Prum challenges the orthodox view of evolution to argue for the importance of beauty, pleasure and desire in shaping the natural world

A Thing of Beauty…

Emma Clark visits the Luohan at the Temple Gallery in London

The Audley Chantry Windows, Hereford Cathedral

Hilary Davies contemplates the work of stained-glass artist Thomas Denny which gloriously expresses the vision of the 17th-century poet Thomas Traherne

READERS’ COMMENTS

As an artist who doesn’t believe that there is a God or Gods, this is ‘challenging’, to say the least (and to say it as politely as I am able).

“At the heart of Tagore’s cosmology is the notion that the world is joyously sung into being. This creative sonic effusion is not a singular burst of divine activity but is continually resounding through the cosmos in ever-new forms.”