A Thing of Beauty _|_ Issue 14, 2019

Mary, Seat of Wisdom and Mercy

Jane Carroll explores the vision of the Virgin Mary embodied in the structure and glass of Chartres Cathedral

Mary, Seat of Wisdom and Mercy

Jane Carroll explores the vision of the Virgin Mary embodied in the structure and glass of Chartres Cathedral

Chartres Cathedral, situated about 50miles southwest of Paris, is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and in its form and imagery expresses many profound meanings which she embodies – not only for Christians, but universally, as a symbol of the feminine. In this article, Jane Carroll, who for many years has studied the cathedral and the sacred geometry that underlies its structure, explains how the building is a monument to the great school of knowledge that developed at Chartres in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Within this, Mary is depicted above all as the ‘seat of wisdom’ – the completely receptive place in which knowledge and mercy appear.

“In her body, as in a temple, the Godhead dwelt for a time.” Adam of St Victor

“In her body, as in a temple, the Godhead dwelt for a time.” Adam of St Victor

From the central crossing in Chartres Cathedral, at the heart of the building, before the modern altar was placed there in the late 1970’s, it was possible to look in each direction to the glorious medieval glass windows depicting four major images of the Virgin Mary. To the west she is enthroned in heaven in the central lancet window. To the north she is shown as a child in the arms of her mother, surrounded by the Old Testament prophets from whom she is descended. To the east she receives Gabriel at the Annunciation. And to the south she is crowned in glory with the child in her arms, the evangelists and prophets on either side – the means through which the prophesy is fulfilled. It is to Mary that the cathedral is dedicated, specifically to the Assumption of the Virgin, and in its form and imagery it gives many clues as to the profound meaning this figure had for the twelfth-century builders.

There is very little information given about Mary in the New Testament. The apocryphal gospels tell a little more, but the centrality of the Virgin throughout the centuries and throughout the Christian world extends far beyond the historical record. Her foundational image as the recipient of the divine breath of the spirit has allowed her to take on multiple forms in many cultures, absorbing pre-Christian and local goddess figures into her reality. Marina Warner has pointed out in her book Alone of All her Sex [1] that there was no cult of virginity in first-century Judaism; Mary therefore concords more with the Greek goddess Athena, virgin deity of wisdom, sprung directly from Zeus, than any figure in the Old Testament.

Chartres Cathedral, view from the south-east. Photograph via Wikimedia Commons

The Building of Chartres

We know from Roman sources that the area around Chartres was an important centre for pre-Christian worship and that there was a very early church there dedicated to Mary. The first bishop dated from the mid-fourth century and by 876 CE, when Charles the Bald gave the sancta camisa, the sacred relic of the Virgin’s tunic, to the cathedral – originally a gift from the Empress Irene to Charlemagne – Chartres had become a major centre for the veneration of Mary.

By the eleventh century, Chartres had also become a famous place of learning and the particular focus of studies there bears a direct relationship to the reality of the Virgin as understood by the scholars. From Bishop Fulbert [/] in the tenth century – characterised as ‘the venerable Socrates of the Chartres academy’ – through the neo-Platonist Bernard of Chartres [/] and his brother Thierry [/] in the eleventh, to the twelfth-century masters William of Conches [/] (commentator on the Timaeus) and John of Salisbury [/], scholars at Chartres were famous for their concentration on the appearance of this world according to divine order. Specifically, they were concerned with the study of the seven liberal arts – the orders through which manifestation appears in word through grammar, logic and rhetoric, and in form through music, arithmetic, geometry and astronomy. It was at Chartres that the term ‘Universal Nature’ – of which Mary is a symbol – was first employed in a medieval Christian context as the basis on which these forms appear.

By the twelfth century, Europe was undergoing a renaissance. New works from Greece and Rome were filtering up from Islamic Spain, many with Arabic commentaries, and the School at Chartres was at the forefront of these studies. Scholars from Chartres travelled to the School of Translation in Toledo, and beyond, to bring back works. There was an emphasis on the study of nature through which universal ideas revealed themselves: Adelard of Bath [/] produced the first translation in Latin of Euclid’s Elements, and Herman of Corinthia, likewise, of Ptolemy’s Planisphere (dedicated to Thierry of Chartres). The School had an extensive library which even included the first edition of the Quran in Latin.

Interestingly, twelfth-century France also produced three impressive and influential women: Marie de France [/] wrote the famous love stories collected in her Lais [2]. Heloise [/], student and lover of Abelard, was herself a great scholar and independent thinker. Most powerful of all was Eleanor of Aquitaine [/], wife of two kings and mother of three, a great patroness of the arts. She was the granddaughter of William IX, the ‘Troubadour Duke’ who was influenced by Arabic love poetry. Eleanor’s granddaughter, Blanche of Castille [/], donated the great North window at Chartres.

When the Romanesque cathedral of Bishop Fulbert burned down in a spectacular fire in 1194, it was discovered that the sacred relic of the Virgin’s tunic had been saved. It was consequently understood that the Virgin herself had determined that a new and more glorious cathedral should be built in her honour. Thus an extraordinary confluence of events coalesced into the building of the magnificent cathedral we have inherited today. The intellectual foundation was given by the great scholars and mystics of the Chartres School operating in the expansive enquiry of the twelfth century. Architecturally, the time and the place had been prepared for the birth of Gothic, which let the light into the interior – the greatest leap forward in engineering the enclosure of space in more than 1000 years. But the emotional and spiritual impulse was generated by veneration of the Virgin.

This veneration brought help and funding from throughout Europe, from princes and paupers. Carrying the stone to the cathedral from the nearby quarries was considered a spiritual discipline, and any who wished to join in had to “renounce anger and malice and to reconcile himself with his enemies in agreement and peace” [3]. Through these efforts, the cathedral was substantially completed in an astonishing 29 years and has survived mostly intact until today: the most complete and perfect image of the wisdom of its time.

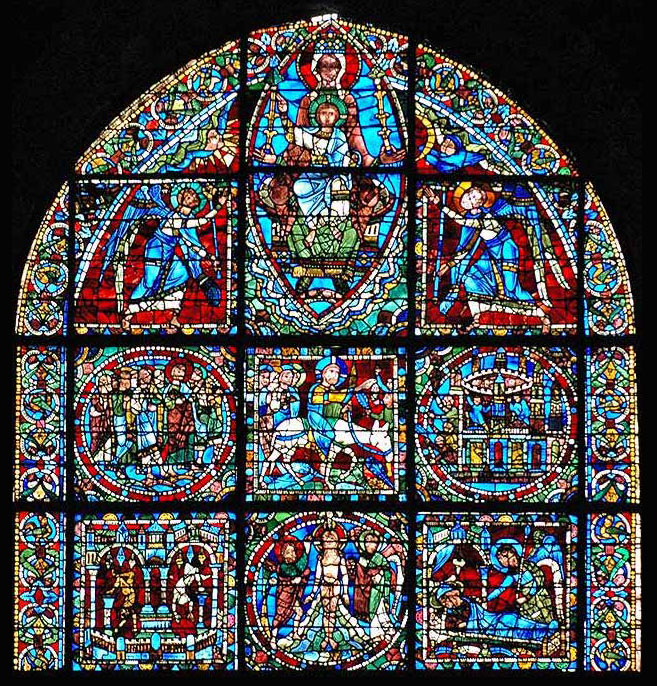

The upper section of the Incarnation Window, showing Mary within the vesica piscis. She is enthroned, with the Child, the embodied divine wisdom, sitting on her lap. Below, the images set in alternating circles and squares depict scenes from the life of Jesus. This window is one of the few surviving parts of the eleventh-century Romanesque cathedral. Photograph via Wikimedia Commons.

The Seat of Wisdom

.

The cathedral has no tombs. The space itself breathes life. There are very few medieval representations of the crucifixion: when it does appear in the medieval glass, Christ is shown on a green cross – the Tree of Life. Images of daily life and the cycles of the seasons appear throughout in glass and stone, connected to the biblical stories and their underlying meanings. The relic which is so central to the cathedral’s fame is the tunic worn by the Virgin at the nativity, not the usual missing fingernail or other part of a dead body. The dedication is to the Assumption of the Virgin, a doctrine not formerly adopted by the church until 1950, but well accepted in the twelfth century as the belief that Mary was carried by angels to heaven after her death. She, like Christ, left no corporeal remains and represents an entity both fully human and divine.

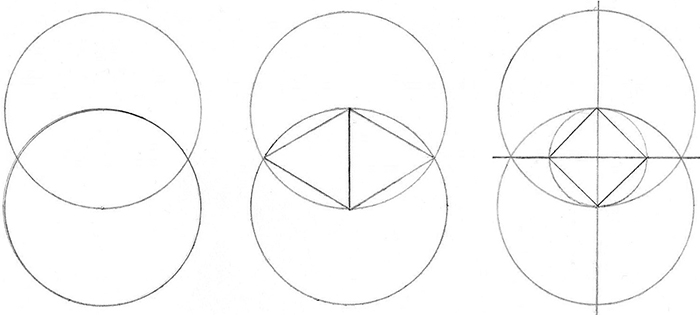

The vesica piscis. Left: The one, the image of the one and the relationship between them. Middle: Three-ness – the shape of the Vesica contains equilateral triangles. The proportion width to height is ![]() . Right: Four-ness – width and height set out the four directions and the square

. Right: Four-ness – width and height set out the four directions and the square

She appears at the summit of the beautiful twelfth-century west window – the Incarnation Window – inside the form of the vesica piscis, the same shape in which Christ is shown in his Second Coming in the sculpture on the West portal immediately outside. This shape, formed at the intersection of two circles, symbolises the place where the human and the divine, this world and the other, are one. It is also, in geometric terms, the form which divides the circle into three-ness and four-ness: three represents the Trinity of the spiritual realm, four represents dimensions of this earth. The number seven – the sum of the three and the four – is the number associated with Mary. It appears throughout the western trio of windows, which has seven circles of glass and seven squares in the central panel, whilst the Passion window to the south has fourteen roundels; and the Tree of Jesse window to the north has seven figures relating Jesus, through Mary, to the Old Testament prophethood. The images are stunningly beautiful and carry meanings within meanings.

The central figure of Mary, embraced by the vesica piscis, is seated on a throne – an image which recurs throughout the cathedral. This is the sedes sapientiae, the throne of Solomon, seat of wisdom. The Child, the Logos, sits on her, holding a book. To either side are images of the sun and the moon which were associated with Mary from the passage in Revelations: “And there appeared a great wonder in Heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet” [4].

This image summarises the reality of Mary as expressed at Chartres: she is the completely receptive place in which wisdom appears. This world, known to be no other than the external appearance of the One Truth, is the place in which the knowledge reveals itself. She is Universal Nature, the materia prima on which knowledge is revealed.

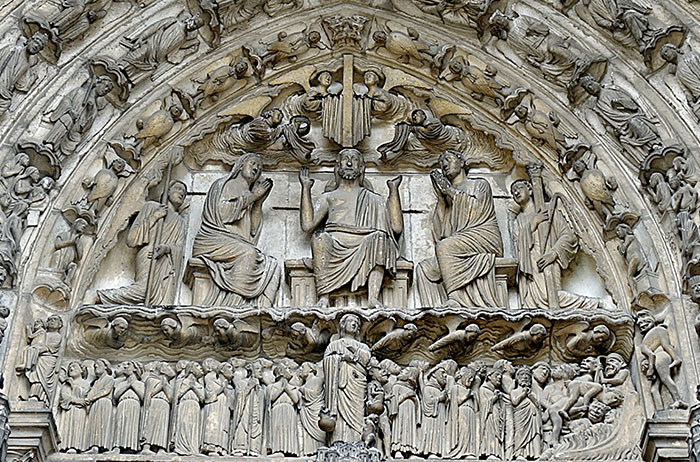

Christ in Judgement on the South Porch, with Mary and John either side. Here Mary appears as intercessor, pleading mercy for the souls who, below, are being separated into the saved and the damned. Photograph: Jane Carroll.

Judgement and Mercy

.

She is also the representative of mercy. Images of the Last Judgement appear throughout the cathedral in quite graphic detail, with the good being led to heaven and the sinners thrown gruesomely into hell. Christ sits in judgement in the sculpture at the south door, with Mary to his right pleading for mercy. Her role as intercessor is recounted in a number of medieval stories. In these she exhibits a distinctive character, often operating outside the rules of law, protecting adulterers, robbers, and incorrigible sinners who turn to her for help. There is a delightful story in the medieval text The Miracles of the Virgin [5] of an abbess who falls into wantonness with her page and conceives a child. She appeals for help to the Virgin, who spirits the child away before it is discovered. The guilty abbess nevertheless confesses her sin to the bishop, who is so impressed that the Virgin has helped her that he brings the child back to his mother. The child grows up to become a bishop and everything ends happily.

The cathedral as a whole embodies the New Jerusalem, the Celestial City after the Last Judgement when universal peace reigns. The harmony of its proportions miraculously conveys the sublime and the compassionate at the same time: a feeling of awe and a sense of comfort. “Art is the circumscribed science of unlimited things”, said John of Salisbury [6]. But peace cannot be achieved without justice – hence the scenes of reckoning. “True peace is not merely the absence of tension, it is the presence of Justice”, said Martin Luther King.

Justice requires judgement but it does not require punishment. What Mary represents is the possibility of atonement overriding punishment. Appeals to her invoke a universal mercy extended over even the most hopeless sinner. For the visitor to the cathedral, whether a medieval believer or a twenty-first-century agnostic, the relationship between receptivity and mercy is embodied there in the glass and stone and the magnificent space, made available to us all.

Notre Dame de la Belle Verrière, or the Blue Virgin, at the centre of the window (also eleventh century) in the south ambulatory. Here again, Mary is sitting on the sedes sapientiae, the throne of Solomon, with Jesus on her lap holding a book, symbolising knowledge. On either side, the angels support her throne. Photograph: John Kellerman / Alamy Stock Photo

The Vesica Piscis

A point that goes into the circle,

inscribed in the square and the triangle:

If you find this point, you possess it,

and are freed from care and danger;

Herein you have the whole of art,

If you do not understand this, all is in vain.

The art and science of the circle

Which, without God, no one possesses.

A saying of the late Gothic stonemasons [7]

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner picture: The Nativity. Detail from the Incarnation Window on the west wall of the Cathedral, one of the eleventh-century windows which survived the fire of 1197. Photograph: FORGET Patrick/SAGAPHOTO.COM / Alamy Stock Photo.

First inset: Mary, holding a book symbolising knowledge, in the arms of her mother, Anne, on the North Portal of the cathedral. Photograph: John Kellerman / Alamy Stock Photo.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] MARINA WARNER: Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary (1976: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[2] MARIE DE FRANCE, The Lais of Marie De France, translated by Glyn Burgess (Penguin Classics,1999).

[3] The Bishop of Rouen, in a letter to the Bishop of Amiens. Quoted in TITUS BURCKHARDT: Chartres and the Birth of the Cathedral, translated by William Stoddart (Golgonooza Press, 1995), p. 61.

[4] Revelations, 12:1.

[5] BENEDICTA WARD: Miracles and the Medieval Mind: Theory, Record, and Event, 1000–1215 (University of Pennsylvania Press; revised edition, 1987).

[6] Metalogicon, Book 1, Chapter 3.

[7] See C. Alhard von Drach, Das Hüttengebeimnis com gerecht-en Steinmetzen-Grund (Marburg, 1897), quoted in TITUS BURCKHARDT: Chartres and the Birth of the Cathedral, translated by William Stoddart (Golgonooza Press, 1995), p. 104.

Jane Carroll studied with Keith Critchlow at the Architectural Association in London, where she wrote her senior thesis on ‘The School at Chartres’. She now practices in Ojai, California. She has studied sacred geometry for many years, and has given many lectures and seminars on the meaning, in particular, of the Alhambra and other buildings in Spain, and the geometric insights of Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

A Thought at Christmas…

What is the universal significance of this festival celebrated at a pivotal moment of the year?

A Thing of Beauty…

The Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Mosque

Calligraphy – A Sacred Tradition

Distinguished calligrapher Ann Hechle talks about her lifelong quest to understand the underlying unity of the world

Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

A visit to a new memorial which aims to heal a dark period of American history

READERS’ COMMENTS

I thought your readers would be interested to know about my visit to the cathedral at Chartres, which will show that The Virgin Mary can be present in our lives today.

A few years ago, my wife had a cancer of the throat, which was quite advanced. I made a vow that if she were cured I would make a pilgrimage. She was cured. We go to France often so I made my pilgrimage to Chartres. I was brought up a Methodist so knew nothing of religious images. It was a Sunday and the cathedral was packed. I had no plan in mind and we could not move around. There was a statue of the Virgin nearby so I went to the statue and just said “Thank you”. There is simply no simple explanation of what happened then. She came into me. That’s all I can say. I felt her. There was a service and people were receiving communion. I wanted to participate but a voice inside me said “You are not worthy”. The I heard the Virgin saying “If you do this, your life will change forever”