Methaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 11, 2018/19

A Thought at Christmas…

What is the universal significance of this festival celebrated at a pivotal moment of the year?

by Mark Vernon

A Thought at Christmas…

What is the universal significance of this festival celebrated at a pivotal moment of the year?

by Mark Vernon

CHRISTMAS is bigger than Christianity. This is partly because the feast falls at a pivotal time of the year when the days hover at their shortest, at least in the northern hemisphere. The brevity of the sun’s appearance makes people conscious of relying on artificial light, and that can, in turn, raise an awareness of the need for spiritual light. Sparkling decorations, lit candles and shining angels appear in streets and windows. They suggest the universal allure of radiance.

The importance of light was recognised by many of the early Christians. Alongside Jewish traditions, they drew on Greek philosophy when talking of the light coming into the world. They borrowed from similarly themed Egyptian imagery, too – for example, drawing on Isis and Horus when imagining Mary and Jesus. This interweaving led Augustine to remark in the fifth century that Christianity was the latest name given to the true religion that exceeds any particular religion.

So how can the mystical dimensions of this festival be recovered in a culture that so frequently seems to have lost such spiritual sight? Owen Barfield, who, alongside C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, was a member of the Oxford group ‘The Inklings’, might have an answer. It is to do with our experience of time.

Barfield argued that humans have ceased to feel that time is the playing field upon which divine purposes unfold. Instead, time has become a detached indicator of the moment when something happens, or it is declared an illusion when set against the timeless truths of eternity. In both cases it is drained of inner vitality and inherent meaning. It ceases to be richly known and deeply felt. It is rendered empty, like an idol.

“To idolatry, an event is either historical or symbolical,” Barfield wrote in Saving the Appearances: “It cannot be both”. Which gives us a clue. If time could become both again, so as to be participated in as chronological and appropriate – as ‘timely’, it might be said – then, perhaps, the bigger meanings of this time of year would be recovered.

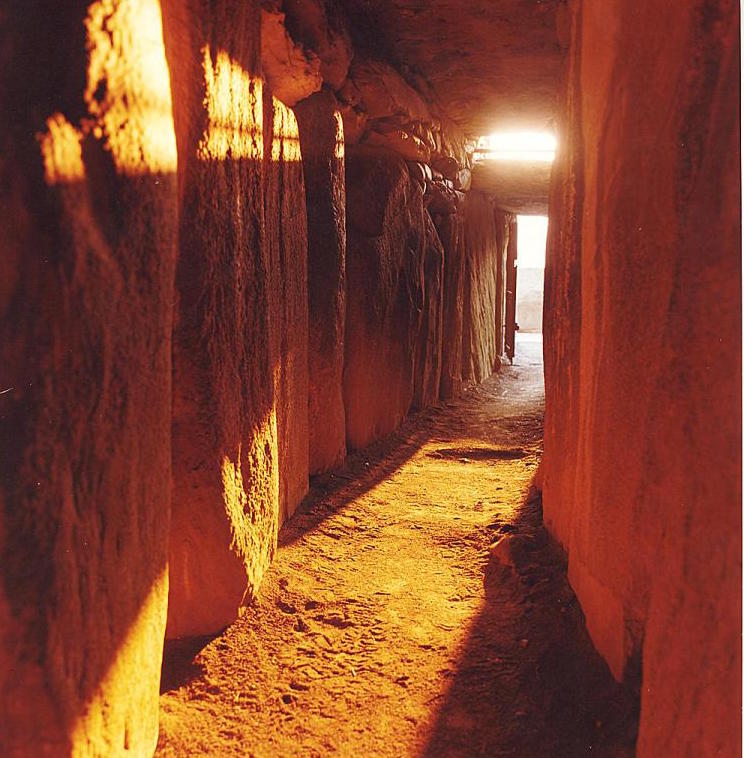

Some effort is being made nowadays to remake this older consciousness. Take gatherings at places like Stonehenge and Newgrange for the winter solstice. The low light and long shadows transform these ancient stone structures into both calendars and wombs. They can simultaneously mark the historical turning of annual cycles, and the symbolism of transitioning between death and life. The ‘both/and’ sense of time is felt again. The light fades to darkness so that darkness can be rekindled by light.

The prehistoric site of Newgrange in County Meath, Ireland. Its grand passage, dated around 3200 bc,

is designed so that the light floods through the ‘roofbox’ filling the inner chamber with sunlight

at the winter solstice. For more, click here [/]. Photograph: History Ireland blogspot [/]

Christmas adds a related turning-point. It became so important in the West, Barfield argued, because it commemorates the change in human consciousness that altered the original experience of time and the seasons.

He came to this conclusion by treating words as ‘fossils of the mind’. Much as biological fossils can be used to track physical evolution, so too can the etymology of words be used to track the evolution of the human psyche. Consider the very old word, pneuma. In the ancient world, it could mean ‘wind’, ‘breath’ and ‘spirit’ because these three things were experienced as part of the same phenomenon. Today, though, we separate them out: wind is a meteorological fact, breath a biological feature, and spirit has been siphoned off.

The fossil-word, therefore, reveals a shift that is also a separation: a change in human consciousness that tends to split inner from outer meanings. It shows that there has been a semantic move from ‘both/and’ to ‘either/or’. Barfield is not the only person to have noted it. Others include Jeremy Bentham and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Barfield spotted something else, though. This separation became pronounced and irresistible at around the time of Jesus, and it is captured in the words of the New Testament. It can be seen in the well-known passage like John 3:8: “The wind bloweth where it listeth… so is everyone that is born of the Spirit.” This translation severs the concepts of ‘wind’ and ‘spirit’, because in the Greek original the word is the same, pneuma. This is a text that has become impossible to translate because our consciousness is no longer what it once was; wind is now a metaphor for spirit, not part and parcel of the same occurrence.

Barfield called the older sensibility ‘original participation’. It was a way of knowing life with little or no differentiation between what is inner and outer, ‘me’ and ‘not me’, mortal and immortal, historical and symbolical. It shifted around the birth of Christianity to what he called ‘reciprocal participation’. Then it began to become possible for a person to call their inner life their own and, at the same time, to discover the ways in which individual interiority reflects external reality. As a result, new phrases appeared, such as: “as above, so below; as within, so without…”. Rituals like sacrifice were spiritualised into virtues; it became possible to talk of having a ‘sacrificial attitude’. And the first Christians came to think that a person had lived who could be simultaneously identified with the divine and yet was also a human individual. This reciprocal experience of life was, henceforth, the deepest realisation of life for anyone. The insight was subsequently developed in other traditions.

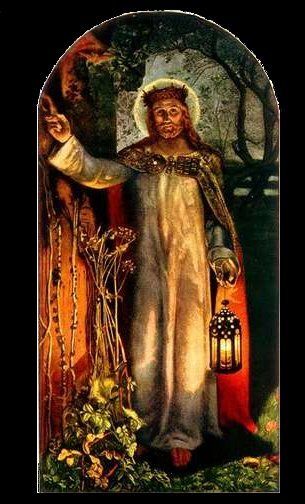

The Light of the World by William Holman Hunt,

based on Revelation 3:20: “Behold, I stand at the door and knock…”

When someone remarked that the door was defective because it had no handle,

Hunt replied: “The door is the human heart; it must be opened from within”

But today, human consciousness is different again. We live after the move from ‘both/and’ to ‘either/or’. It came about for a variety of reasons, not least of which is the scientific revolution. It generated numerous technological benefits, but also the odd situation in which the more we are able to manipulate the world, the less we are able to perceive its meaning. There has been a loss of spiritual sight. Time has become merely a marker; history, one event after another. Christianity has become a belief system that you either follow or you don’t, and thus parochial. Its adherents cease to see that the festival shares in a truth that exceeds it, available for everyone’s participation and perception.

The task now is to regain the spiritual sight that can see this – “to find at our turn of the spiral of time what it means to be at one with the earth and the sky”, suggests Philip Carr-Gomm in The Druid Way. That would be what Barfield called ‘final participation’, and focusing on time as both history and symbol at the Christmas turn of the year is a good way to seek it.

How might time regain its weight as a journey, a path, a pilgrimage? How could it become as resonant as a place, a relationship, a book? Is it possible to grasp, with John Keats, that “a man’s life… is a continual allegory”? What would it be to experience time, once more, as the moving image of eternity, the continual incarnation of the divine, the route that returns us to God?

Know that, and we might also know the universal meaning of Christmas and the reason that Jesus, at one moment in time, came into the world. It would be to see the light that enlightens everyone, the life that can be enjoyed in all fullness, and the reality of being born of the Spirit.

Chora tou achetou (The Container of the Uncontainable) is a representation of the Virgin and Child which originated in the Greek Orthodox tradition. Within the Catholic Church, it became known as ‘The Seat of Wisdom’ [/]. This example is found at the Chora Museum in Istanbul. Photograph: Peter Horree [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

… and a Poem

Bird Psalm

by U. A. Fanthorpe

The Swallow said,

He comes like me,

Longed-for; unexpectedly.

The superficial eye

Will pass him by,

Said the Wren.

The best singer ever heard

No one will take much notice,

Said the Blackbird.

The Owl said,

He is who, who is he

Who enters the heart as soft

As my soundless wings, as me.

Detail from Nativity by David Jones, with birds and animals.

Image: from a private collection

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: Nino Marcutti / Alamy Stock Photo.

Other Sources (click to open)

Owen Barfield, Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry (1957; Barfield Press, 2011), p. 197.

Hermes Trismegistus, “As above, so below; as within, so without; as the universe, so the soul…” in G. Lachman, The Quest for Hermes Trismegistus (Floris Books, 2011) p. 16.

Philip Carr-Gomm, The Druid Way (Thoth Publications, 2006), p. 24.

John Keats, “A man’s life of any worth is a continual allegory, and very few eyes can see the mystery of his life – a life like the scriptures, figurative”. Written in a letter to his brother George, in 1819. See W.J. Bate, John Keats (Harvard: Belknap Press, 1963), p. 204.

Dr Mark Vernon is a psychotherapist, writer and broadcaster. He contributes to programmes on the radio, writes and reviews for newspapers and magazines, gives talks and podcasts, including a series with scientist Rupert Sheldrake [/]. His next book, to be published in 2019, is on Owen Barfield, and is entitled A Secret History of Christianity: Jesus, the Last Inkling, and the Evolution of Consciousness. His previous books have included, The Idler Guide to Ancient Philosophy (Idler, 2016); Love: All That Matters (Hodder Education, 2013); and The Meaning of Friendship (Palgrave MacMillan, 2006). He has a PhD in ancient Greek philosophy, and other degrees in physics and in theology. For more see markvernon.com

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Getting Back in Time.

Richard Gault argues that technology has radically altered our relationship to time

Bewildered by Love and Longing

James Turrell’s installation at Dorotheenstädtischer Friedhof, Berlin

Mysticism in Comparative Perspective

Professor George Pattison talks about the revival of a unitive approach

Painting and the Contemplative Life

Artist and psychotherapist Benet Haughton talks about the spiritual vision that underpins his life and work

READERS’ COMMENTS

Genius awakens Genius – Light delights in Light – a valuable article and beautiful poem – thank you.

Perhaps Mark would like to see what is said concerning the reality of Christ in the Chapter on Jesus in the Fusus al Hikam by Muhyiddin ibn al ‘arabi. Much of this is expressed in the novel Fish See Water, which deals with the importance of The Annunciation for a profound understanding of the meaning of the appearance of Jesus.

I just wanted to say how much I enjoyed all the articles, but particularly the one on time. I would like to thank Richard for writing such an excellent and thought-provoking piece.

A deeper look at how words change ideas and how words change themselves is, it seems vital to understanding the purpose of all. To consider we ‘know’ how ancient people thought is an example of what the writer brings out, our disconnection with the unfolding universe of Light