Finance & Global Affairs _|_ Issue 10, 2018

Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

Jane Carroll visits a new memorial which aims to heal a dark period of American history

Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

Jane Carroll visits a new memorial which aims to heal a dark period of American history

In the first of two articles in which we explore contemporary reconciliation movements, Jane Carroll contemplates the opening of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Alabama, USA, which took place in April 2018. This commemorates, for the first time, the thousands of African Americans who were lynched in the southern states of America in the years after emancipation. This project is just one example of memorials recognising injustice and oppression now being created all over the world. This is an entirely modern phenomenon, seeming to indicate a new kind of commitment to peace and forgiveness.

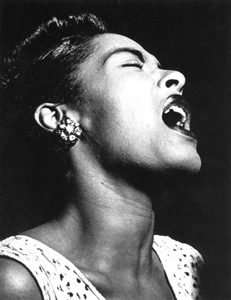

Billie Holiday’s most haunting song opens with the line “Southern trees bear strange fruit [/]”, which perhaps provides the most focus that many people, other than African Americans, have given to the horrors of the mass lynchings which took place in the Southern states of America between the 1860s and 1940s. Now there is a powerful memorial to the victims of this era – the National Memorial for Peace and Justice [/] – built on a hillside above the State Capitol building in Montgomery, Alabama. It is a kind of classical temple, but instead of colonnades of white marble, these columns are of rusted steel and hang from the roof. Each one represents a county where a lynching took place and bears the names and dates of the victims.

Billie Holiday’s most haunting song opens with the line “Southern trees bear strange fruit [/]”, which perhaps provides the most focus that many people, other than African Americans, have given to the horrors of the mass lynchings which took place in the Southern states of America between the 1860s and 1940s. Now there is a powerful memorial to the victims of this era – the National Memorial for Peace and Justice [/] – built on a hillside above the State Capitol building in Montgomery, Alabama. It is a kind of classical temple, but instead of colonnades of white marble, these columns are of rusted steel and hang from the roof. Each one represents a county where a lynching took place and bears the names and dates of the victims.

A quote from Martin Luther King, engraved at the entrance, lays out the intentions of the Memorial:

True Peace is not merely the absence of tension, it is the presence of Justice.

Montgomery is the right place for such a monument. In the heart of the South, it was the centre of the domestic slave trade in 19th-century America, but also the cradle of the Civil Rights movement, beginning with the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 when Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her seat for a white passenger. It was where Martin Luther King had his first church and became the spokesman of the movement at the age of 26. It was also, in 1956, where he gave the sermon from which the quote above comes.

Both the Memorial and the Legacy Museum which has been built alongside it are the inspiration of Bryan Stevenson [/], author of a best-selling book, Just Mercy, and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative [/], a public interest law organisation which defends death row inmates and is committed to “protecting basic human rights for the most vulnerable people in American society”. In his work, and in the memorial and accompanying museum, he makes the powerful case that real peace requires justice and that justice requires accountability.

Each of the 800 hanging steel columns represents one county, on which are listed the names and dates of the people who were lynched there. Photograph: Madeleine Jettre/dbimages; Alamy Stock Photo

Stevenson felt it was imperative to tell the story of the more than 4000 men, women and children who were victims of lynching. If this story has been known by most Americans as an unfortunate but minor repercussion of emancipation, almost all African-American families know it intimately. They have memories of the domestic terrorism which caused more than six million people to abandon their homes, their businesses and their communities – only recently established after emancipation. As an engraving in the Memorial tells us:

Lynchings in America were not isolated hate crimes committed by rogue vigilantes. Lynchings were targeted racial violence perpetrated to uphold an unjust social order.

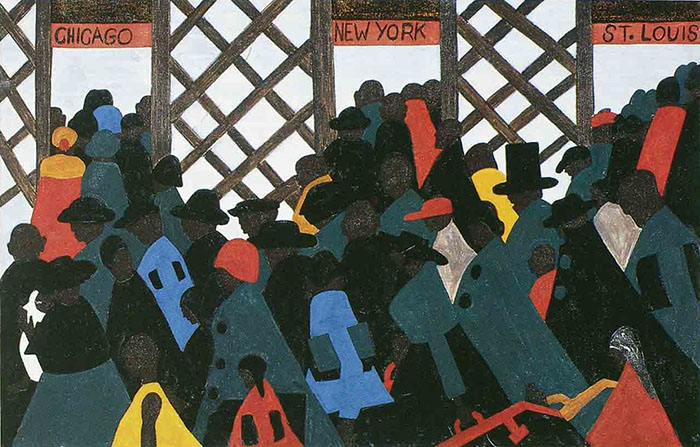

The subsequent movement of the African-American population to the northern cities, where they were to encounter other forms of discrimination, constitutes the largest mass migration in US history. The Legacy Museum draws a line connecting slavery through the period of lynchings and the Jim Crow laws [/] in the South to the mass incarceration of people of colour today. Stevenson wants this story told in order to understand the present – “not to punish America but to liberate it”.

Jacob Lawrence, ‘The Migration of the Negro, Panel no.1.’ One of a series of paintings on the migration of African Americans from the south to seek jobs in northern industries during and after World War 1. Photograph: Granger Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo. For more information on the Migration series, see https://lawrencemigration.phillipscollection.org/the-migration-series

A Global Movement Towards Reconciliation

The Memorial in Montgomery opened just three years after the impressive National Museum of African American History and Culture [/] in Washington DC, which was a long time coming. Before this there was no major memorial to the history of these people in the Nation’s capital. Similarly, the National Museum of the American Indian [/] only opened in 2004. These examples demonstrate how hard it is for a country, as it is for an individual, to own and thoroughly examine the darker sides of their histories. The USA is not the only nation to have this problem. Britain still has no major national museum examining its role in the Atlantic slave trade or the effects of colonialism. Much more common are memorials to a nation’s victories, or to the victims of its enemies – soldiers or martyrs for instance.

The establishment of places or processes through which we can examine our own past wrongs is actually a new phenomenon, and the desire to create them can be seen as part of a global movement which is taking place towards reconciliation and forgiveness. Stevenson was inspired to set up the Alabama Memorial by examples in other parts of the world, in particular the Holocaust Museum [/] in Berlin, the Apartheid Museum [/] in Johannesburg, and the Kigali Genocide Memorial [/] in Rwanda which commemorates the million Rwandans killed in the 1994 civil war.

A sculpture by Kwame Akoto-Bamfo confronts visitors upon entering the Memorial grounds. Photograph: Jeremy Graham/dbimages; Alamy Stock Photo

Some people have objected to this kind of exhumation of the past with its implication of guilt and responsibility, but interestingly, none of the memorials mentioned have demanded punishment in pursuit of justice. One descendant of a lynched victim who spoke at the opening weekend of the Memorial in April described the pain of her family, who had been forced off 400 acres of a profitable farm in the 1880s and whose children and grandchildren had faced years of hardship in the north. Now that the crime has been acknowledged and a plaque erected in the hometown of her great-grandfather, she feels at peace. She does not require the land to be returned; she just needs the truth to be told. This echoes the sentiments of the victims who have come forward in the #MeToo movement [/] and the child sexual abuse scandals which have hit the headlines in recent years: the demand for justice has often required only that the crime be made manifest and people’s experiences be acknowledged.

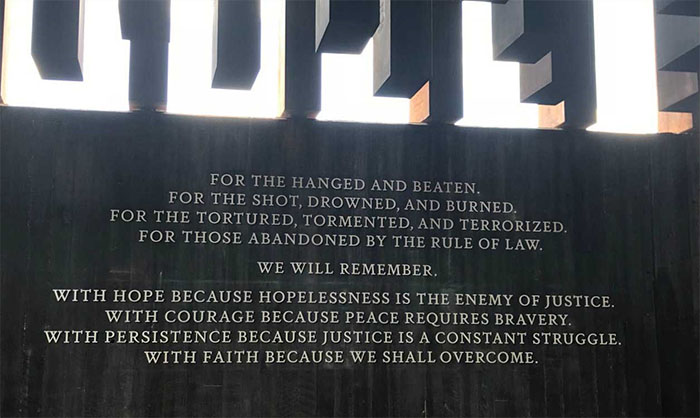

As for the fruits of such self-examination, Archbishop Desmond Tutu [/], one of the founders of the South African Reconciliation Movement which was implemented to heal the wounds of Apartheid, has pointed out that we cannot move forward by just covering over or forgetting past injustices: “Bygones will not be bygones just because we say so”. We have to face up to the past in order to come to a proper understanding of ourselves and our world, and it is only through this that we can ensure that such things will not happen again. Thus the opening statement to the Memorial begins:

We believe that telling the truth about the age of racial terror and reflecting together on this period and its legacy can lead to a more thoughtful and informed commitment to justice today. We hope that this Memorial will inspire individuals, communities and this nation to claim our difficult history and commit to a just and peaceful future.

The exterior of the Memorial. Photograph courtesy of EJI

Justice and Love

The Memorial itself accomplishes something profound: it is solemn but ultimately inspiring. It is a beautiful and simple building, a four-sided colonnade, its path slowly descending around the quadrants. The columns all hang at the same level: on the first side they are at eye-level, compelling the visitor to read and engage with each name. The second side begins to descend below the level of the columns and by the third side the columns rise above the head in an overwhelming mass, inducing tears in many of the visitors. At the last quadrant, a fountain and a place to rest in front of an uplifting exhortation to fight for justice offers a way to process the impact, and to recognise that this is an active healing space. In the gardens outside lie facsimile columns – each destined for the county in which the victims were lynched, when those counties are prepared to accept and display them.

The interior on the opening weekend. Photograph: Jane Carroll

The official opening of the Memorial and Museum in April included three days of talks and discussion, powerful sermons and, this being an African-American event, sensational music. Bryan Stevenson gave a deeply moving and personal speech about the work he has been engaged in for so many years. He described a seminal moment when he had to tell an inmate on death row that he had lost his final appeal. Stevenson was devastated and felt so broken by this defeat he intended to give up the work. But it was when the inmate thanked Stevenson for his efforts on his behalf and told him that he loved him that Stevenson realised that though he had been striving for justice, the motivation behind it has always been love: it was love that demanded that justice, and the peace that would unfold from it – and love that has kept him going.

Bryan Stevenson. Photograph: courtesy of Equal Justice Initiative / Human Pictures

This motivation runs through the Memorial. Many attendees of the opening weekend remarked that the experience of walking through the columns was not ultimately depressing nor anger provoking. Rather, it induced a sense of wholeness, not division – a sense that this process of reconciliation is for everyone, not just the manifest victims. On leaving the Memorial and entering the gardens there is a quote from Toni Morrison’s [/] Beloved:

O my people out yonder, hear me… hear me now.

Love your heart. For this is the prize.

Quote: EJI Photograph: Jane Carroll

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: ‘Raise Up’, a sculpture by Hank Willis Thomas, in the grounds of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Photograph: Audra Melton.

First inset: Billie Holiday.

Other Sources (click to open)

Billie Holiday, ‘Strange Fruit’. For a recording, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Web007rzSOI. For more on the song, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strange_Fruit

Bryan Stevenson, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption (Speigel & Grau, New York; reprint 2015)

For more on Equal Justice Initiative, see https://eji.org

For more on Jacob Lawrence’s ‘Migration Series’ see https://lawrencemigration.phillipscollection.org/the-migration-series

Toni Morrison, Beloved (Vintage Classics, New York, 2007)

For an interview with Toni Morrison see http://www.alainelkanninterviews.com/toni-morrison

Jane Carroll studied at the Architectural Association in London and practices in Ojai, California. She is also the secretary of the Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi Society in the US

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Tell Them What We Have Learned Here…

Chronicles from World War II of a remarkable group of 20th-century philosophers

A Thing of Beauty…

Frank Lloyd Wrights’s masterpiece, Fallingwater in Western Pennsylvania

A New Architectural Language for Islam

The inclusive vision of Glenn Murcutt’s Australian Islamic Centre

A Thing of Beauty…

The Chagall Peace Window and the Meditation Room in the United Nations building, New York

READERS’ COMMENTS

Congratulations.

I saw documentary – True Justice – about lynching

and enjoy very much . Things were almost the same

in Brazil.

Love

Otavio

Great post! I learned something new and interesting, which I also happen to cover on my blog. It would be great to get some feedback from those who share the same interest about Robotics, here is my website Article Star Thank you!