A Thing of Beauty…

David Apthorp praises the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Mosque in Istanbul

A THING OF BEAUTY…

David Apthorp praises the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Mosque in Istanbul

The Sokullu Mehmet Pasha Mosque is one of the masterpieces of Islamic architecture. Built at the highpoint of the Ottoman Empire, it was designed by the great architect, Mimar Sinan, using an intricate six-fold geometry imbued with spiritual significance. The interior decoration is one of the best examples of Iznik tile work, produced just before the secret of the fabulous coloured glazes began to be lost. Visiting 500 years after its inauguration, geometer and artist David Apthorp finds that it still has the power to enthral us.

This small jewel of a mosque in Kadırga, the part of Istanbul that nestles between the foot of the first of the seven hills of old Constantinople and the sea of Marmara, looking towards the shores of Asia, was designed in the late 1560s by Mimar Sinan, the greatest of the Ottoman architects. It beautifully encapsulates the profound spiritual and artistic vision which underpinned the earthly rule of the Ottoman Empire.

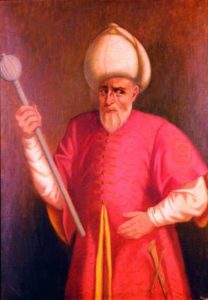

The mosque was built for the daughter of Sultan Selim II (r.1566–74), Esmahan Sultan, who was married to his Grand Vizier, but it very soon became known by the name of her illustrious husband. Sokollu Mehmet Pasha served three sultans between 1565 and 1579. He was made Vizier under Suleyman I Kanuni – the Lawmaker, known in the west as Suleyman the Magnificent (r.1520–66) – and his political acumen and skill in controlling the rivalry between the two surviving contenders for the throne of the ageing Sultan, and his role in ensuring that his father-in-law, Selim, could safely accede, gave him pre-eminence in the Ottoman court. He became enormously wealthy and powerful, and during the rule of Selim – who was reputedly more interested in wine, poetry and his beloved Venetian wife, Nurbanu – he was de facto ruler of the empire.

The mosque was built for the daughter of Sultan Selim II (r.1566–74), Esmahan Sultan, who was married to his Grand Vizier, but it very soon became known by the name of her illustrious husband. Sokollu Mehmet Pasha served three sultans between 1565 and 1579. He was made Vizier under Suleyman I Kanuni – the Lawmaker, known in the west as Suleyman the Magnificent (r.1520–66) – and his political acumen and skill in controlling the rivalry between the two surviving contenders for the throne of the ageing Sultan, and his role in ensuring that his father-in-law, Selim, could safely accede, gave him pre-eminence in the Ottoman court. He became enormously wealthy and powerful, and during the rule of Selim – who was reputedly more interested in wine, poetry and his beloved Venetian wife, Nurbanu – he was de facto ruler of the empire.

His friend Marcantonio Barbaro, the Venetian ambassador – who was also a patron of Palladio – described his motivation for building the mosque in glowing terms, praising his character, his piety, graciousness and lack of ‘rapacity’…

He constructed a lofty madrasa and house of knowledge at the courtyard of the joy-giving Friday mosque and soul-expanding place of worship which he built with a thousand artful wonders at Kadırğalimanı near the Hippodrome as a gift for his illustrious wife, her Highness the Sultana…

And for the group of dervishes, who divest themselves from the contamination of the gilded wheel of fortune by retiring like a spider to the corner of contentment and who substitute litanies in praise of God for worldly quarrels, he built behind that light filled Friday mosque a convent with thirty defectless rooms embodying beautiful characteristics.

Naturally, he commissioned the royal architect, Mimar Sinan, to design the mosque. Sinan had learnt his trade as engineer on the campaigns of Suleyman I, making fortifications, bridges, roads and aqueducts. He was appointed chief royal architect at about age 50 and held the post for almost 50 years, gaining mastery as he went. His career ran in parallel to the great renaissance architects such as Palladio, Michaelangelo and Leonardo Da Vinci. By the time he built the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha mosque, he was in his late sixties and the acknowledged master of form and materials. He was also one of the most influential architects in the world; just a few years earlier he had designed the Suleymaniye – the iconic complex honouring Suleyman – which has given Istanbul one of, if not the most, instantly recognisable skylines of any of the world’s cities. And a couple of years later, he would complete his masterpiece, the Selimiye in Edirne, which is considered to be one of the highest achievements of Islamic architecture.

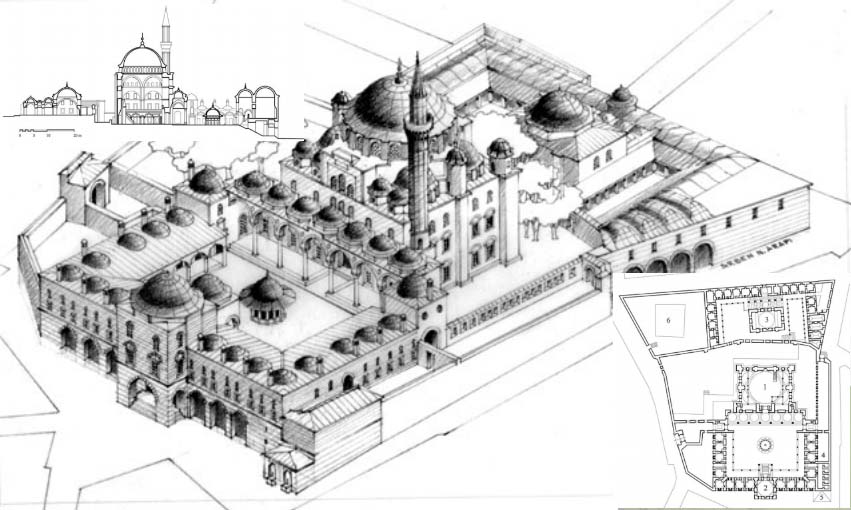

The Sokollu Mehmet Pasha was built on a sloping site below the Vizier’s own palace – which is no longer standing, as the land was sold by his son for the construction of the so-called Blue Mosque, built by Sultan Ahmet (r.1603–17) in the early 17th century. Behind it, as Barbaro indicates, was constructed a dervish convent for the Halveti Shaykh Nureddinzade, the Shaykh of the Küçuk Ayasofia convent, whose enthusiastic adherents included not only Sokollu Mehmet but also Sultan Suleyman and Princess Mihrimah, his wife’s royal aunt.

Drawing of the whole Sokollu Mehmet complex: https://www.studyblue.com/notes/note/n/second-half/deck/1679638

NEVER MISS AN ARTICLE

Please follow and like us:

CATEGORIES

The perfect use of the sloping terrain, coupled with the classical symmetry and elegance of the structure, solves with unparalleled grace the difficult issue of whether this is the Friday mosque of a Grand Vizier – which has a well-defined place in an architectural (and thus political) hierarchy – or the Mosque of a Royal Princess – which has quite another.

The Experience of the mosque

If you want to visit this jewel, I suggest you leave it till last on your itinerary. First witness the grandeur of the mighty buildings on top of the seven hills – the great Church of Justinian, the Hagia Sofia, dedicated to the Holy Wisdom; the mosques of Suleyman, Bayazid and Sultan Ahmed; the Topkapı Palace. Sense the strength and power that gave rise to them and then walk back down the hill, as a pilgrim might, bringing with you an awareness of the thousand years of history that the city’s architecture embodies. As you walk towards the sea, round the corner of a building, at eye level you will suddenly see the curve of a dome, and – whether by accident or design, we do not know – an optical illusion that has the single, twelve-sided, minaret soaring straight out of its centre. The half domes and turrets tumble down in perfect harmony into the trees, like tresses.

Approaching from the city. Photograph: Rowanwindwhistler (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0]

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

If you follow the slope of the wall you will catch glimpses, behind the stones, of a flash of muqarnas (a form of ornamental vaulting) through a small arch, but do not enter here. It is better to go on down and round to the main entrance; an arch with steps leading blindly up in the blank monumental wall, two stories high. As you walk up, you experience a seeming miracle; on the fifth step – which is deliberately made a little wider to invite a pause – the dome of the fountain suddenly appears, filling the frame of the arch. As you continue, the main dome seems to rise like a dark sun against the sky behind it. And at the next pause, the golden finial, with its star and crescent, points at the panel of calligraphy on the facade: Ashaddu ‘an la ilāha ila Allāh wa Mohammad al-rasūl Allāh – I witness that there is no god but God, and Muhammad is His messenger: the Islamic Profession of Faith. The finial on the dome above, topped with what looks like a Tibetan vajra, points straight into the sky.

View from the entrance steps. Photograph: gezmen / Alamy Stock Photo

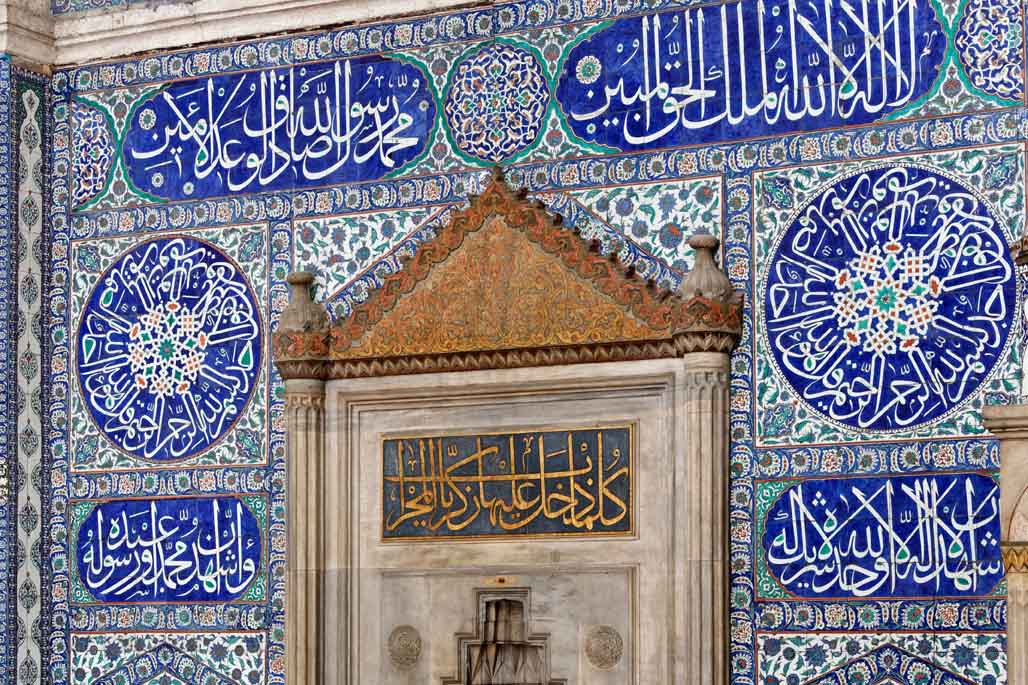

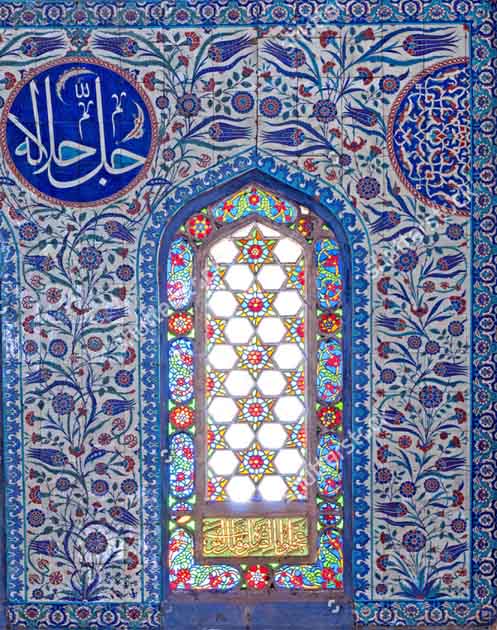

As you enter the courtyard, the rest of the facade unfolds on either side. Past the fountain lie the seven arches of the royal portico where, in each bay above the windows, panels of exquisite tiled calligraphy spell out the seven verses of the Fātiḥa, the opening chapter of the Qurʾān, which comprises the primary rite of Islam, the prayer which is repeated five times a day. Then, as you enter the main mosque and your eyes become accustomed to the light, you will see, soaring on and on up the opposite wall surrounding the mihrab (towards which all Muslims face in prayer) an arched garden, a paradise of tiled flowers and stained glass windows. Wheeling in rosettes on either side of the fragment of the Black Stone that is set into the wall there is another calligraphy, the Surat al-ikhlās which indicates the inner purity of the religion and the highest aspiration of its followers. There are actually four fragments of the Black Stone in the mosque, given to Sokollu in gratitude for paying for the renovation of the Kaʿba.

Interior of the mosque. Photograph: imageBROKER / Alamy Stock Photo

This wall of Iznik tile work, like the mosque itself, represents the peak of its art, for within a matter of decades, the quality of tiles being manufactured began to deteriorate, never to regain the excellence of the late 16th century. The array in the Sokollu Mehmet is the largest single illustration in Iznik ceramic, containing the three major elements of Islamic art – namely calligraphy, geometry and biomorphic patterns – in a beautifully co-ordinated and integrated way. And it tells a geometric story; above the plinth level tiles (which are described as faux marble but could be clouds separating the Garden of Paradise from this earthly realm) stylised flowers curl up in repeating symmetrical patterns on either side of the mihrab. The pattern, based on the height of a human, is repeated three times below the calligraphy cartouche and the wall is divided vertically into three as well, with the undecorated mihrab being a third of the overall width. The number of small flowers in the band that runs up each side, enclosing the whole, matches the number of surahs in the Qurʾān. Above the panels of calligraphy, beyond the cornice, in the intermediary realm of the half domes and clerestory windows, the flowers are much freer and more naturalistic, and somehow other-worldly.

The mihrab wall. Photograph: Westend61 GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

In the rest of the mosque, the tile work is kept to a minimum and is tied to metaphysical necessities. The pendentives are exquisitely tiled, apparently freeing the dome from the bonds of earth. The star-studded muqarnas that hide the squinches of the half-domes do the same. As Augusto Romana Burelli has said:

For Sinan, decoration tended to reconcile opposites. He seemed to say: ‘I will build a perfect machine animated by great constructive energy, but all traces of this energy must disappear: the dome must seem as if suspended…

and from the metaphysical standpoint, the dome is indeed a ‘seeming’ and is, in truth, as all the universes are, suspended from the Divine Bounty…

‘.. and the materials must be hidden by precious coverings.’ The muqarnas, for example, cover the points of the greatest concentration of lines of force… Sculpted in honeycombed shapes, almost dripping from the vertical plane, they give the impression of being suspended. Meanwhile, Sinan used painting and ceramic tiles to form a covering composed of small, brightly coloured motifs repeated on a light background. By thus luminously adorning the walls, he removed any sense of crushing weight.

The side windows. Photograph: Kernan Kaya/Shuttlestock

There are panels of tiled calligraphy above the windows, containing the ninety-nine Most Beautiful Names of God – indicating, perhaps, the real source of the light that enters the building through them. Small medallions under the apexes of the eight subsidiary flat arches which list the names of the four so called ‘rightly guided’ Caliphs – Abu Bakr, ʿUmar, ʿUthman, ʿAlī – plus Hassan and Hussain, and invoke God’s peace and blessings upon them all. The windows in the paradise garden of the qibla wall are stained glass with hexagons of pure light surrounding hexagon stars, like light shining through trees. Elsewhere the windows are plain, with rippling bands of blue glass, like rivulets or tendrils.

Detail of the tilework. Photograph: David Apthorp

Geometric harmony

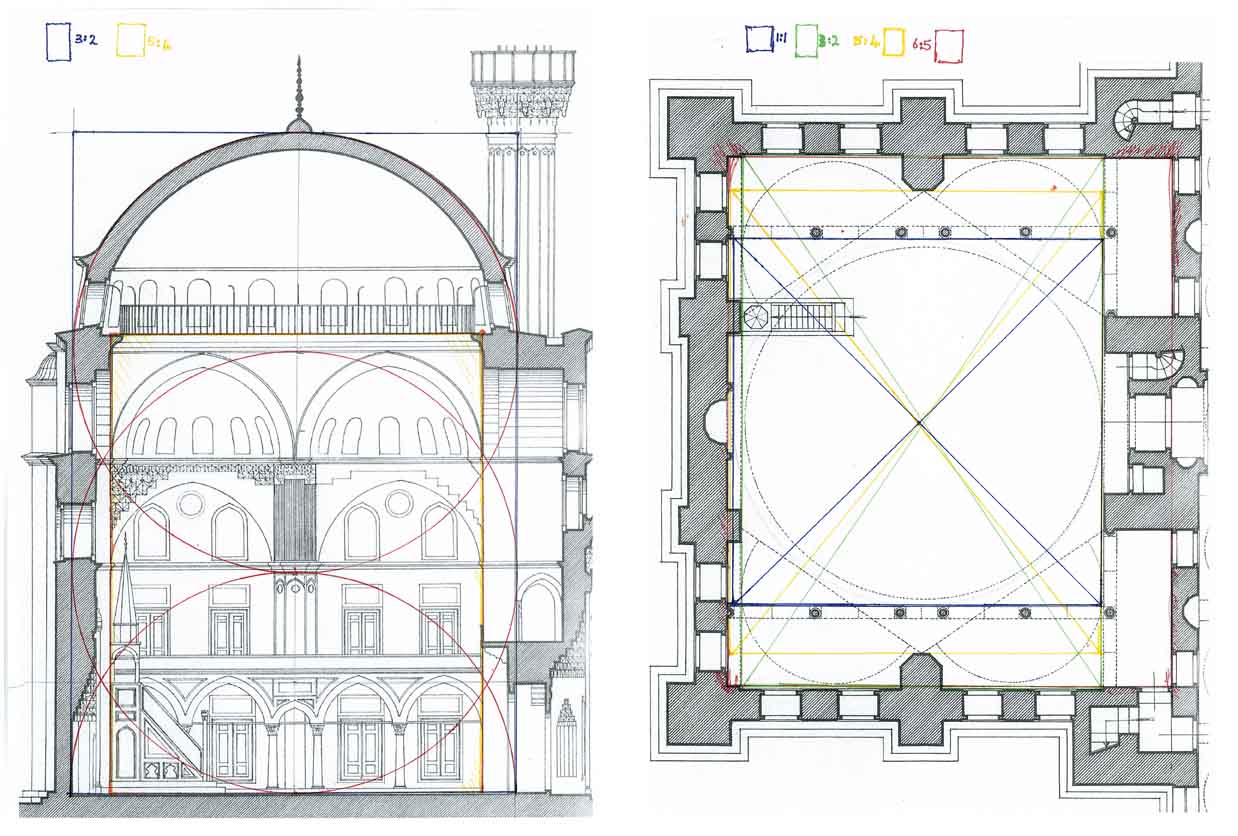

Geometrically, the mosque is designed as a hexagon inscribed in a rectangle, topped by a dome with four small semi-domes in the corners. Its structure represents a high point of Ottoman architecture, which developed over several centuries from a template originally based on the form of the Hagia (Aya) Sophia. This great church, built by Justinian in 537, had long been the object of wonder to the Muslims. There is a famous saying of the Prophet Muhammad that it would become a mosque and that whoever prayed in it would go to Paradise. During the first Muslim attack on the city in 674–8, Mohammad’s standard-bearer, Abu Ayyūb al-Anṣārī, made an agreement with the Byzantine Emperor to raise his siege of the city if he could pray in the Hagia Sophia. He was thus held to be the first Muslim to worship there, and his tomb (he died during a later campaign and was buried outside the city walls) was discovered and rebuilt by Mehmet II when he conquered the city in 1453. All the Ottoman sultans were girded with the ‘sword of Uthmān’ at the Eyüp Sultan Mosque upon their accession, and to this day, it is regarded as a sacred place by the people of the city.

Just round the corner from the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha is the 6th-century Church of SS Sergius and Bacchus, one of the most beautiful and historic of the surviving Byzantine churches in the city. This is deemed by many to be a prototype of the Hagia Sophia – indeed it is still known as Küçuk Aya Sofya (the little Aya Sophia). Begun by Justinian in 527, the first year of his reign, it was built by the same architect, and the metaphysical themes expressed with such superlative skill and majesty, ten years later, in the Hagia Sophia itself, are here present in miniature and can be seen clearly.

The church of SS Sergius & Bacchus. Photograph: Borisb17/Shutterstock

The church has an octagonal central structure enclosed by external walls constructed on a nearly square ground plan. The design is a deliberate combination of the centralised form of building normally found in Syria and Palestine, topped with a dome, and the basilica, which was the traditional form of Christian church architecture, developed out of the Roman meeting hall. The idiosyncratic structure which results can be described as a ‘domed basilica’. In terms of meaning, the aim is to unite and enfold in a single structure the sphere of Heaven and the cube of Earth (following Plato). Marking out the arc of the heavens and enclosing a vast invisible sphere, the form is a particularly apt symbol of the unity proclaimed by Islam, and its single empty space – depicting the void, and thus referring to the ghayb (the Unknowable), the Non-manifest, the Divine Presence – resonated from the very beginning with Muslim sensibility.

This architectural form was adopted and further developed to an extraordinarily refined degree by the Ottomans, and by Sinan in particular. A study of the elements of the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha reveals that the spaces within the mosque itself are arranged according to a hierarchy of proportions, like notes in a scale. The prayer hall between the balconies to the top of the windows in the half-domes is a perfect cube. The overall proportion is 2:3, with the hemisphere of the dome topping the cube of the body of the building. The top of the dome marks the height of the start of the corbling of the balcony of the twelve-sided minaret from where the muezzin calls the faithful to prayer. The faces of the side pillars give you a 5:4 ratio, as does the cornice at the base of the dome. From the side walls to the pillars by the doorway and mihrab wall is 3:2 again, and the overall floor space is 6:5…

The Geometry of the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha. Drawing: David Apthorp.

Meanings

One could say much more: of Sinan’s perfect resolution of the hexagonal form; of the meaning of the number six itself, the first ‘perfect number’ which is the sum of its dividers (1 x 2 x 3 = 6 ; 1 + 2 + 3 = 6); of the Üç Serefeli mosque which is another very lovely, earlier (15th-century) mosque in Edirne where the dome is supported by a hexagon; and of all the paths that cross and recross during the thousand year journey – both metaphysical and physical – that started with the church of SS Sergius and Bacchus and culminated in this beautiful little mosque.

But standing here, before the plain, unadorned mihrab, it as if one has been brought to some ultimate secret – as if there is an opening, as it were, in the centre of Paradise. In physical orientation, one is facing back across the water to the origin of it all – to the prophetic message that inspired both Christianity and Islam. In the interior, one faces the unity – the intersection between the visible and the invisible, beauty and ineffability.

And in history, one is facing a peak moment in art and spiritual culture, a glint of light on the topmost drop of water in a fountain before it falls. For after the death of Selim II in 1574, Sokollu Mehmet found himself disliked by the new Sultan, Murad III (r.1574–95), a weak and untrustworthy monarch who found the great plans of the Grand Vizier (including one for a Suez canal!) an unwelcome interference with his begetting of 102 children from the countless wives and concubines supplied by his mother and his Venetian wife. In 1579, Sokollu was murdered in the Topkapı by a beggar dervish of the persecuted Hamzawi order, at the behest of a ‘foreign agent’, and the Empire entered upon its long period of decline.

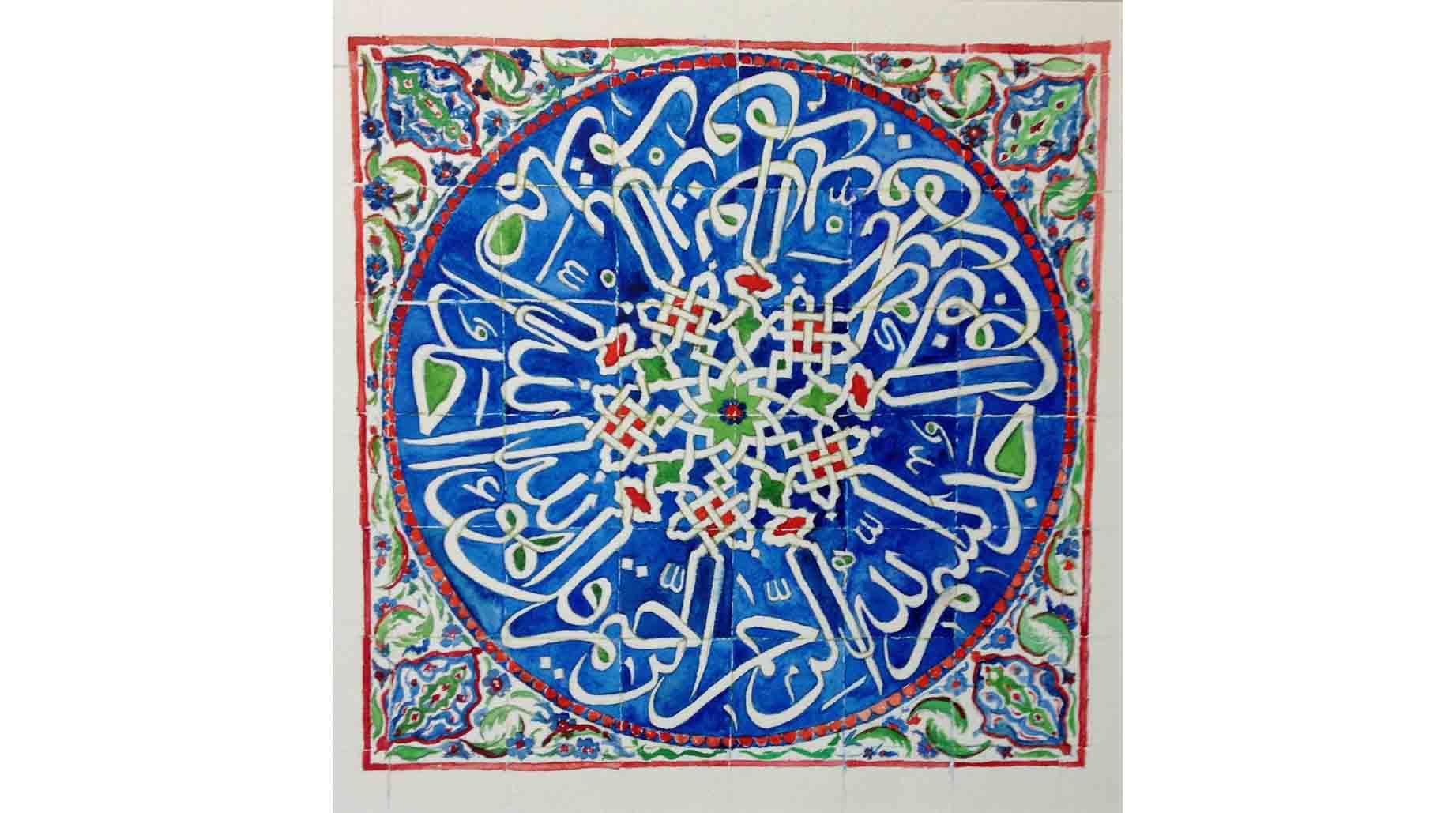

Painting of the Sura on Purity (Ikhlās) by David Apthorp

Email this page to a friend

Email this page to a friend

Image Sources

Banner: The dome and the minaret of the mosque, looking out over the Sea of Marmara. Photograph: Hackenberg-Photo-Cologne / Alamy Stock Photo.

First inset: Portrait of Sokollu Mehmet Pasha: artist not known.

Other Sources

Quote by Barbaro from Gülru Necipoğlu, The Age of Sinan (Reaktion Books, 2007), p. 332.

Quote from Romano Burelli in John Freely, Augusto Romano Burelli & Ara Guler in Sinan: Architect of Suleyman the Magnificent and the Ottoman Golden Age (Thames and Hudson, 1992).

David Apthorp is a painter, carpenter and joiner who has had a long-term interest in sacred geometry, art and architecture. This led him to take an MA in Islamic Art at the Prince of Wales’ School of Traditional Art, where his special interest was in Ottoman architecture and its place in an unfolding art of the sacred. He also spent a number of years working on the restoration of Chisholme House in the Borders of Scotland. Now retired, he continues to live in the Borders with his family.

David Apthorp is a painter, carpenter and joiner who has had a long-term interest in sacred geometry, art and architecture. This led him to take an MA in Islamic Art at the Prince of Wales’ School of Traditional Art, where his special interest was in Ottoman architecture and its place in an unfolding art of the sacred. He also spent a number of years working on the restoration of Chisholme House in the Borders of Scotland. Now retired, he continues to live in the Borders with his family.

NEVER MISS AN ARTICLE

If you enjoyed reading this article, please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

Please follow and like us:

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE:

0 Comments