Remarkable Lives _|_ Issue 21, 2022

Neurodiversity and Creativity

Catalysing Change through Artful Agitation: a conversation with artist and researcher Dr Kai Syng Tan

Neurodiversity and Creativity

Catalysing change through artful agitation: a conversation with artist and researcher Dr Kai Syng Tan

Dr Kai Syng Tan [/] is an artist, curator, researcher and consultant who is a senior lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University. She has participated in more than 900 shows worldwide and is known for her interdisciplinary/intercultural approach. Her motto is ‘Catalysing Change through Artful Agitation’. Since 2015, when she was diagnosed with ADHD, she has become an advocate for the notion of neurodiversity – the idea that many unusual cognitive profiles, such as autism, are differences rather than disorders. In 2017–18 she initiated a major arts/science collaboration at King’s College London to explore the idea of ‘mind wandering’ and is the co-founder of the Neurodiversity In/And Creative Research Network. Jane Clark talked to her in her office in Manchester via Zoom.

Jane: Can we begin by talking about what is meant by neurodiversity?

Jane: Can we begin by talking about what is meant by neurodiversity?

Kai: In terms of its genesis, it was coined by the Australian sociologist Judy Singer [/] in the 1990s. It arose really out the autistic self-advocacy movement, and basically expresses the idea that cognitively there are many different ways of being human; people have different brains, different minds, different modes of communication and different modes of behaviour. Singer’s aim was to get away from the idea that there is some sort of norm or ideal from which some people fall short. The term also has an alignment with the idea of biodiversity – that on this planet, there is an enormous variety of living beings and every one of them has a place.

Jane: So the argument is that these conditions like autism or dyslexia should not be regarded simply as a disability or a clinical condition, but rather an expression of difference?

Kai: Not just in terms of expression, but that the diversity is meaningful and valuable. Historically, it has been the autistic community and advocates of autism that have been the most vocal in terms of pushing forward with the idea. But now the term has become expanded to include people with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyper Disorder), dyslexia, dyspraxia and other so-called ‘specific learning difficulties’. In the network that I have set up, people who identify with conditions outside of even these ‘classical’ frameworks have joined and shared that they feel that they have ‘found their tribe’ there – colleagues with PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder), or processes like schizophrenia and so on. So it is a term that has different registers and it is defined differently by different communities. It is essentially a political term and Judy Singer has also emphasised this.

Jane: If we think just about the classical range of what are commonly called specific learning difficulties – dyslexia, autism, ADHD, dyscalculia, etc. – how many people are we talking about?

Kai: I think one of the common figures is one in seven. So somewhere around 12–15% of the population overall. When you consider specific processes, then obviously the numbers are much smaller. Autism occurs in about 2% and ADHD in about 3–4% of the adult population. This is certainly an underestimation, as we only know about people who go for a formal diagnosis; as awareness grows and there is more diagnosis, the numbers will go up. There are lots of issues we could discuss concerning the problem of diagnosis, or waiting times – which can be up to five years in the first place – but perhaps that’s another interview!

Jane: But even if we take the one in seven figure, it means that in every primary school class of say, 30 pupils, we expect to find four neurodivergent students, one of whom probably has ADHD, and every other class would have an autistic child.

Kai: Yes. This is a significant number and the educational system is really not geared up to deal with them, to say the least.

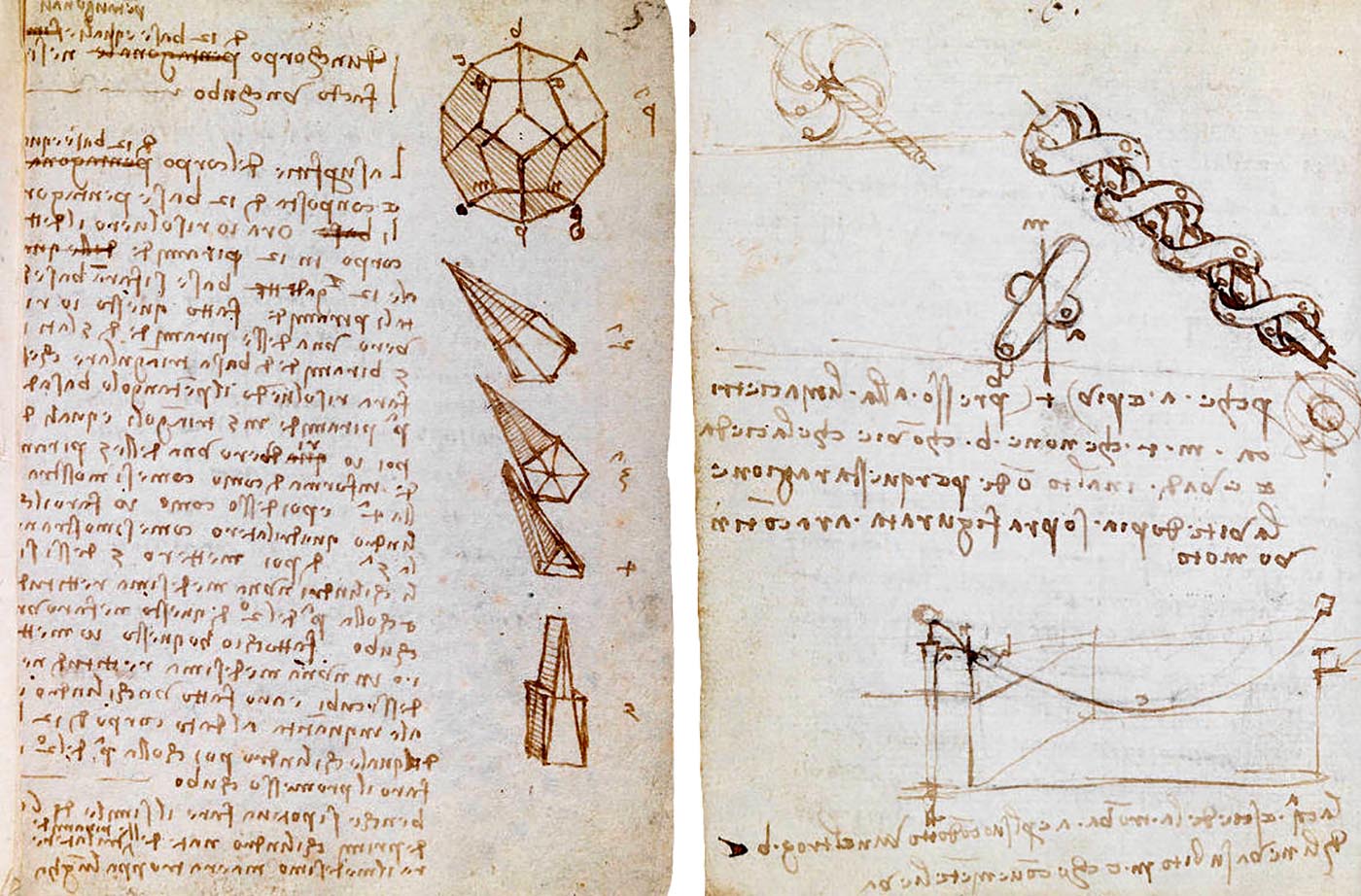

A page from one of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, compiled around 1490. It contains notes and diagrams for devices relating to hydraulic engineering and on the moving and raising of water. Image: Codex Forster I.2, from folio 41, courtesy of the V & A, London. For more, click here [/]

Move your computer mouse over the image to enlarge

Neurodiversity and Creativity

Jane: What is special about your work is that you link the idea of neurodiversity to creativity and argue that these conditions can be a positive asset when coming up with innovative ideas or new ways of doing things. Can you say a bit more?

Kai: Well, I wouldn’t be the first one to make that association. I think that popular literature – which has also contributed to the current interest in neurodiversity – has pointed out that there is a disproportionately large number of people in Silicon Valley who are autistic because of their ability to focus – hyper-focus – on solving problems. There’s also literature out there about how humans have always been distractible in the way that people with ADHD are. And in fact, this was probably intrinsic to human survival. You needed to be alert to all the little noises that you heard outside of your cave or tent or wherever you were living, because you needed to know whether there was a wild animal approaching. So there are all kinds of different stories or even mythologies out there.

I am interested in looking at the situation conceptually and creatively, and asking – if we put neurodiversity with creativity together, what can we get? At the moment, what is dominant is what we call the deficit approach – meaning, that we see neurodivergent processes as problems, disorders and ‘abnomality’. We have a largely medical model that pathologises difference. There is a process of diagnosis, and various ‘remedies’ are prescribed such as special equipment and human support, medication, etc. This essentially puts the onus on individuals to work things out themselves. But, how about we think of flipping things around? As an artist, I love flipping things around, turning them upside down to ask the ‘what ifs?’. And as someone with ADHD, I love trespassing boundaries and borders, and colliding contrasting elements together to make new, novel connections.

Jane: We have a very good example of someone who’s autistic making a huge difference in the world in Greta Thunberg. She has spoken about her autism as being an intrinsic part of what she’s doing – not a disadvantage – because she sees things in a different way. But there are many other neurodivergent people who have done remarkable things – and there is even a movement now to look back at historical figures, and say, oh, they must have had dyslexia or dyspraxia or something. The two most quoted cases are perhaps Albert Einstein, who struggled with writing and spelling, and Leonardo da Vinci, who would almost certainly be diagnosed as dyslexic today because of the mirror-writing we see in his notebooks.

Kai: Leonardo da Vinci is a good example because he was not just dyslexic but probably also ADHD.[1] He was a professional dabbler and enjoyed crossing freely the boundaries of knowledge in science and art, painting and drawing, biology and engineering. I say ‘dabbler’ because he was conceiving all these wonderful things – flying machines and such like – but he never built them: they never literally took off! He had a kind of intellectual promiscuity. And I think that’s absolutely a good thing.

But I work in higher education and I know that today, he would never have made it into any university, let alone any university assessment programme, because nobody could read his mirror writing. While this has been the delicious subject of many a speculative fiction and blockbuster movie, it was almost certainly, as you say, due to dyslexia.[2] Also, he probably wouldn’t know which subject to choose because we have created all these artificial specialisms in today’s knowledge world.

So Da Vinci is a wonderful poster boy for neurodiversity, but there are many many others. I would particularly mention the young businessman, Chin Hwee Tan, who was the World Economic Forum Young Global Leader in 2010 and 2014; or the artist Marvel Harris. Joshua Wong – the Hong Kong pro-democracy leader – is also someone I would like us to pay more attention to as he has talked about being dyslexic. He started going out in the streets when he was in his teens, much like Greta Thunberg, and has very much capitalised on being atypical. Of course it is dangerous to make the claim that these people are successful because of their dyslexia or their autism – I have spoken about the danger of the ‘superpower’ trope in being reductive and falling prey to essentialism and exceptionalism, replicating existing biases. Nonetheless, there is so much prejudice and misunderstanding about neurodivergent processes that it is important to draw attention to ‘atypical’ people who have made their mark in the world.

Neurodivergent people who have changed the world. Clockwise from top left: Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong; IT developer Bill Gates; science fiction writer Octavia Butler; musician John Lennon; (Images: 湯惠芸 via Wikimedia Commons; Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken via Wikimedia Commons; Nikolas Coukouma via Wikimedia Commons; Dom Slike [/] / Alamy Stock Photo)

Changing the World

.

Jane: You’ve said that acknowledging this kind of creativity is important not only at an individual level, but for the future of humankind, because we really need to start thinking in new ways now. And you’re not the only person saying this: there is a widely circulated quote by the writer Harvey Blume: “Neurodiversity may be every bit as crucial for the human race as biodiversity is for life in general. Who can say what form of wiring will prove best at any given moment?

Kai: That’s right. Because the standard that we have at the moment is not working. I mean, there’s a war going on as we speak, and we have children who are starving in the first world. When I migrated to England from Singapore, I thought that it was the bastion of democracy and found it shocking when I discovered what is actually happening in this country in terms of inequality and deprivation. The normative – typical – ideas of leadership don’t work anymore, so we need new ones – a ‘new norm’, which was what was trumpeted in the wake of Covid but which we seem to have strangely forgotten now.

So my proposition is: people from minoritised backgrounds have already been exemplifying creative leadership – how else would we have survived in a normative world that hasn’t been built for us? So, perhaps it’s time to listen to the ‘abnormal’ who have non-standard strategies and proposals. Yes, we have figures like Greta Thunberg and Joshua Wong questioning our norms. But what if these people were the architects and designers of our social systems? What would that look like?

Jane: As part of this imaginative exercise, you have begun to identify the kind of characteristics we would actively embrace if neurodiversity was in charge. One of them which I found particularly interesting – because it conforms so well with the aims of Beshara Magazine – is the need to step out of our ‘silos’ and develop what you call ‘360 degree vision’.

Kai: Absolutely – for example: one of the big divisions we have in our education systems at the moment is between arts and sciences – that is, what are called STEM subjects (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics). But maybe we don’t have to choose between them, but rather, learn across the disciplines like Leonardo da Vinci did. This is in fact already happening; University College London has been the pioneer of an undergraduate, and now postgraduate degree, in Arts and Sciences.

So we are already moving out of these very restrictive categories. What if that were to become a norm? I am, of course, not suggesting that everything would be perfect if we did this, because that would be naïve. Nothing is ever perfect, so we should always be interrogating ourselves and making sure that we are not becoming stagnant. We need to always be thinking about how we can make things better.

That’s one of the propositions. Another one is that is that we need to stop punishing students who are disruptive or just don’t conform to the very restrictive rules we impose on them in the classroom. We need to stop penalising children who look out the window, for instance. I mean, I look out the window; I’m looking out the window as we speak and it does not mean that I am not also paying attention to what we are doing. It might sound counter-intuitive, but many people with ADHD can focus better when they are engaged in more than one thing at the same time. They need to move around a lot as well, and there is no reason why we could not accommodate that within our classrooms – and create new kinds of classrooms in the process.

Jane: There has been some research which shows that it is not only people with learning difficulties who have problems within our educational system. People who are considered intellectually gifted also often find it hard to fit in and do not do well either at school or in life. We are talking about people with very high IQ levels, in the 150s and 160s – and the reason, it seems, is that they view the world in a different way: they see things that other people don’t, or present alternative solutions to problems for which there is considered to be a single answer. We have a system which is very geared to the middle range and it can’t really cope with outliers of any sort.

Kai: Yes. And the outliers are usually the most interesting people, so we should absolutely pay attention to them – and actually, we should be thinking about both ends of the spectrum. There are people who are super-bright, but at the other end there are people who are considered unbright who nevertheless have valuable qualities and insights. So we should always fight against having to conform to the middle, or to what is called the lowest common denominator. Apart from anything else, it is leading to a huge wastage of human potential. My own dad, for instance, cannot count and left school at 14, but he was from the wrong class and wrong era to be get support for his dyscalculia.

We also need to move away from normative definitions of ’success’. For me, human diversity is a given. Everyone is different, and so I don’t know why anyone is so keen to be ‘standard’ or ‘normal’. Why is normality a gold standard? Isn’t it so much more exciting to be different, to have glitter and a phenomenal spectrum of colours and possibilities?

Kai in front of her magic carpet with her colleague Philip Asherson, Professor of Molecular Psychiatry at the MRC Social, Genetic and Developmental Psychiatry Centre, King’s College London, at an event in 2018. Image: Youtube [/]

Mind Wandering and #Magic Carpet

.

Jane: Can you tell us about your own process of discovery, as I believe you found out about your own neurodivergence quite late in life?

Kai: I only got my ADHD diagnosis a few years ago, in 2015. I come from a tropical paradise where, miraculously, difference doesn’t exist! Where mental health doesn’t exist! Where specific learning difficulties and neurodiversity don’t exist! So it was only when I came to the UK to do my PhD that I had the opportunity to have a diagnosis by an educational psychologist.I went along because I was struggling a lot with my PhD. But actually, I had been compensating my whole life. I would not sleep, I would not eat, in order to be in an altered state to stay up all night or wake at 3am to re-process notes from textbooks into something that made sense to me and get my homework done. I had done well because I knew how to cram and could answer the questions in my exams. But so-called ‘success’ came at a really high price. I had always known that I was different, but then, I assumed that everyone is.

When I did the tests they came back positive, firstly for dyslexia, which is now quite well understood. But then the diagnosis for ADHD came through and I did not know what it meant. So I decided that I had to find out. And that was why I started the project with King’s College London’s Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience. I wanted to get to the bottom of what ADHD is, and I wanted to talk face to face with people who consider my brain and my behaviour to be abnormal.

So I went to see Professor Philip Asherson, who is leading research into ADHD at King’s, and this resulted in me becoming the artist in residence at the Institute’s Social, Genetic, and Developmental Psychiatry Centre for two years. It was an arts/science collaboration: I attended lectures and took part in the research projects and learnt about the scientific side of things, and colleagues were able to talk to me and find out about my point of view.

Jane: So can you say something about what you found out?

Kai: Well, one thing that was surprising is that researchers of neurodevelopmental disorders have often become interested because they are neurodivergent themselves, or they have family members who are. But not many of them would disclose that because it would be professional suicide, and they know better than anyone the stigma surrounding neurodivergence. So one of the things we would talk about was the possibilities of working together across the ‘us and them’ binary between psychiatrist and patient, expert and participant or ‘service user’ etc, to help remove the stigma still largely endemic in discussions around mental health.

Move your computer mouse over the image to enlarge

Jane: So as I understand it, you took a specific topic to explore – mind wandering – which is also Professor Asherson’s special area of research. And you set up events and seminars to explore this with people from right across the spectrum, neurodivergent and non-neurodivergent.

Kai: Yes, we went for mind wandering because it is a major feature of ADHD. One of the things I did was to create a tapestry with a design that expressed my own thought processes – my own mind wandering. The short title of the project was #MagicCarpet, and it was a two-year project commissioned by King’s College, and also a disability arts body called Unlimited [/]. I put the tapestry on the floor – thus becoming the ‘carpet’ in question’ – so that I could sit down on it with a psychiatrist, a neuroscientist and anyone else from the field of brain and mind sciences and beyond. So the carpet literally opened up a space – not a clinical space or an educational space, a space in a classroom as such – but a new, creative space where people could talk about difference. They could talk about their mind and the ways it works. My case study was specifically ADHD, but I think a lot of what we talked about can be applied to neurodiversity in general.

Jane: I think we all have some idea of what mind wandering is, but can you say a bit more about what you explored?

Kai: Well, it is a central feature of ADHD that the brain finds it hard to maintain attention on one thing; it is easily distracted and thoughts go wandering off in all sorts of unregulated directions. Mind wandering is a good thing for me and for a lot of artists because it is to do with not staying stagnant; about being curious and finding new adventures and frontiers, both literally and figuratively. When we are staying put in one place, we can’t find new avenues and rabbit holes. And of course, if we talk about how humans have travelled the globe, that’s how we make discoveries. It’s about a kind of insatiable search for something.

So this kind of restlessness can be very positive; but it was interesting to hear what Philip and other psychiatrists have to say in terms of trying to identify when it becomes too much. There is a point where it becomes impairing because if we cannot focus when we need to, it prevents us from achieving what we want to achieve. So where is the tipping point? That is the big question, and I would argue that the answer is contextual and environmental – cultural and social – as much as it is neurological. That links back to our discussion earlier about creating other kinds of classrooms and new art-sciences degrees, etc., to not just accommodate but include and celebrate atypical modalities.

And it leads on to questions about how society thinks about difference. These processes are not black and white; there is a spectrum which we are all on, because as we have already said, there is no ‘normal’. There is a popular saying that we are all possibly ‘a bit ADHD’ today because of the highly distractible kind of society we live in.

Neurodivergent people who have changed the world. Clockwise from top left: climate activist Greta Thunberg; film director Steven Spielberg: singer and song-writer Billie Eilish; entrepreneur Richard Branson. (Images: Marcus Schweizer via Wikimedia Commons; Gage Skidmore via Wikimedia Commons; Lars Crommelinck via Wikimedia Commons; NASA via Wikimedia Commons)

Opening Up Dialogues

.

Jane: #MagicCarpet was a very wide-ranging project, which I understand reached about 10,000 people through face to face events in those pre-Covid times, and without doubt many more online. How do you think that people changed through participating in it?

Kai: The main effect I think was just that a lot of people became able to talk about their own neurodivergence. Many have told me that the project also had a direct impact in terms of changing the direction of their research, or of doing some kind of advocacy and support work for others around them, whether for students or their peers. I think one of the significant factors for me was that I don’t conform to the stereotype of someone with ADHD. I’m a woman and I’m older – a middle-aged woman; I’m not a boy running around in a classroom. And the fact that the encounter was mediated by an artwork gave them a chance to engage with people and materials that they would not normally come across. This is really the aim of all my art: to open up these new, liminal spaces for new dialogues and actions.

Jane: Since the King’s project, you have continued to give talks and seminars on the issue of neurodiversity all over the world; and to have conversations with scientists doing research by sitting on an impressive number of boards and committees. You have also set up an on-line network, called the Neurodiversity In/And Creative Research Network [/]. Can you tell me something about that?

Kai: It really grew out of #MagicCarpet. I began by gathering people who had been participating in the project, and then it kind of grew and now there are 350 colleagues in it. They come not only from the UK but also from India, Canada, the USA, Taiwan and Australia. Judy Singer is in the network, for instance. There are people from academia – professional and academic staff, and lots of postgraduate and PhD students. We also have people from tech, from the cultural sector and so on. And as I mentioned before, there are people with all sorts of profiles; we have people with schizophrenia, people recovering from stroke, people with anxiety, all of which can be re-framed and re-activated as creative resources.

After founding the network, I invited a #MagicCarpet participant, Dr Ranjita Dhital, to co-chair it with me. The speed with which it has grown is an indication of how great a need there has been for something like this. The aim is to be critical friends for one another, to hold the space for one another and to share questions around our research and our practice. We also discuss issues surrounding our difference and our neurodiversity. It is a life resource for anyone who wants to know more about neurodiversity, and at the same time we are becoming something of a critical voice – we are allies in a world which is still an enormous challenge for many people. We are trying to create a model of what an inclusive space, where neurodiversity is foregrounded, can look like.

Jane: Kai, thank you so much for talking to us. We wish you all the best with your projects.

For more about #MagicCarpet, watch this video:

King’s Artist Dr Kai Syng Tan and Professor Philip Asherson, SGDP Centre. Duration: 7:18 minutes

Cartoon by Simon Blackwood

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Kai Syng Tan. Image: Badge-wearing Mind Wanderer in Action (M.I.A) (from #MagicCarpet, 2017). Photographer: Enamul Hoque. Taken from YouTube

Inset: One of the badges which Kai created for #MagicCarpet events, each listing a characteristic of ADHD. Other badges say: ‘always on the go’; ‘easily distracted’; ‘acts without thinking’; ‘talks incessantly‘.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] MARCO CATANI & PAOLO MAZZARELLO, ‘Grey Matter Leonardo da Vinci: a genius driven to distraction’ in Brain, Volume 142, Issue 6, 2019, pp. 1842–1846. Click here [/].

[2] D. SCHOTT, ‘ Mirror writing: neurological reflections on an unusual phenomenon’ in Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 78 (1), 2007, pp. 5–13. Click here [/].

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

A Thing of Beauty…

Mark Boston reflects on painting the film Loving Vincent

Connecting with the Unseen World

Kira Perov, wife and long-term collaborator of the video artist Bill Viola, talks to Jane Carroll about the ideas and experiences which inspire their work

Keith Critchlow: A Life Well Lived

Richard Twinch pays tribute to the teacher and sacred geometer who died on April 8th 2020

d-r-a-w-n-i-n-w-a-r-d

Nicola Simpson on Dom Sylvester Houédard extraordinary 1960s artwork ‘c-dagesh’

READERS’ COMMENTS

Brilliant. I’m one of six children and 5 of them have dyslexia and dysoraxia. They are all left handed also.

I’m the of one out!

I am so called normal but never see myself normal at the same time. It is amazing the work you do. I hope this work gets a lot of exposure as far and wide as possible.

Thank you so much for this. My young daughter is autistic. This is exactly the world that I want to be able to give her.