Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 2, 2016

d-r-a-w-n-i-n-w-a-r-d

TOWARDS THE CENTRE OF THINGS

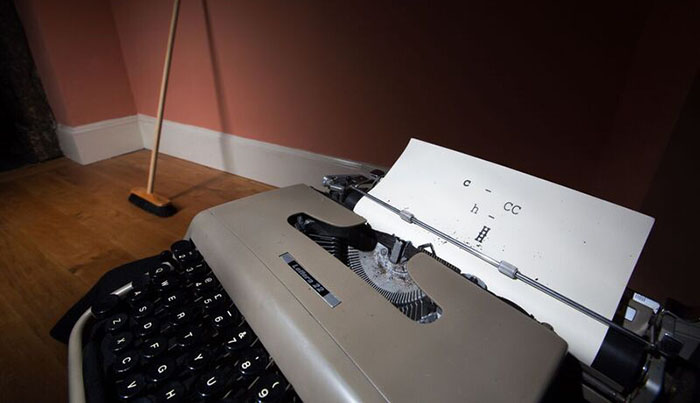

Nicola Simpson on the mystical vision of Dom Sylvester Houédard

d-r-a-w-n-i-n-w-a-r-d

TOWARDS THE CENTRE OF THINGS

Nicola Simpson on the mystical vision of Dom Sylvester Houédard

Dom Sylvester Houédard (1924–1992) was an extraordinary British monk, scholar, translator and concrete poet. He was deeply committed to what has become known as “the wider ecumenism”, that is, finding common ground between the different spiritual traditions. As well as his grounding within his own Christian tradition, he had a profound understanding of both Islamic mysticism and Buddhism. In this article, curator and researcher Nicola Simpson describes how the latter influenced his contribution to a 1960’s happening, Mieko Shiomi’s “Falling Event”, in which he participated alongside Allen Ginsburg and John Cage.

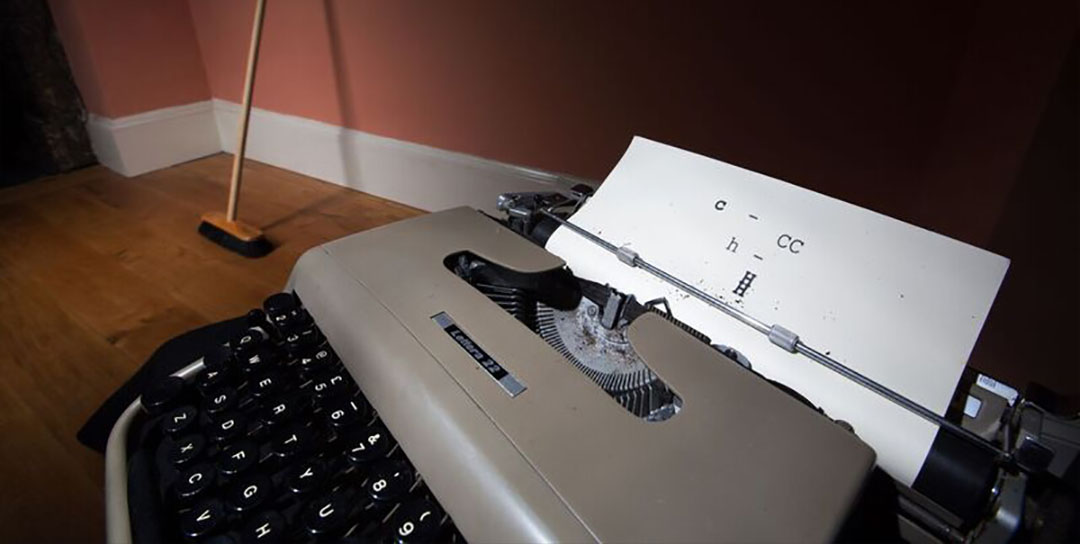

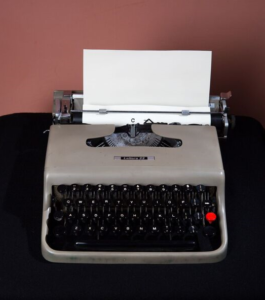

Dom Sylvester Houédard’s reputation and legacy as an artist rests largely on the typestracts he meticulously made on his Olivetti 22 typewriter throughout the 1960s and into the early 1970s. The art critic Guy Brett has said of him:

Dom Sylvester Houédard’s reputation and legacy as an artist rests largely on the typestracts he meticulously made on his Olivetti 22 typewriter throughout the 1960s and into the early 1970s. The art critic Guy Brett has said of him:

[…] a Benedictine monk who spent most of his working life at Prinknash Abbey in Gloucestershire [he was] one of the great unsung intellects and playful creative spirits of twentieth-century Britain.

Describing himself as a “monk-maker”, Houédard was profoundly interested in the experiential non-conceptual truths at the heart of mystical and contemplative traditions, and he found a ready receptivity for his ideas in the vocabulary of the newly emerging conceptual and performative-based art made by a trans-national network of avant-garde artists and poets. As his correspondence, critical writings, and artworks attest, he was always exploring the “coexistence” between his own deepening theological understanding of “the wider ecumenicalism” and the “alive blurring of frontiers between art & art, mind & mind, world & world, mind art & world” of “post-WW/2” avant-garde art (See Notes from the Cosmic Typewriter, 2012).

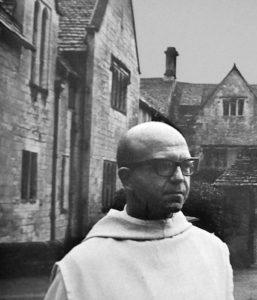

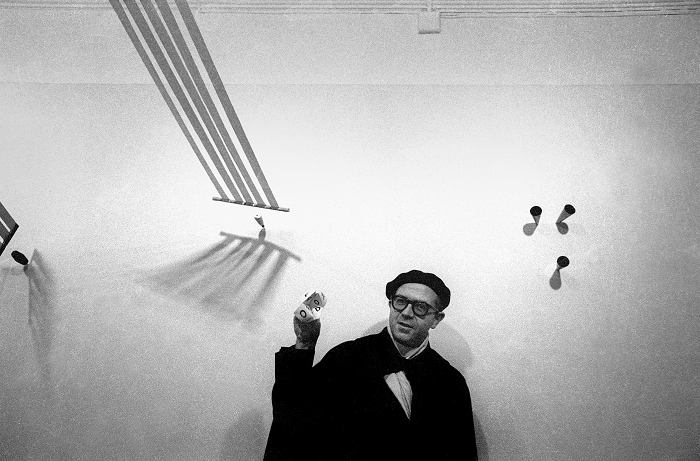

Dom Sylvester Houédard at Signals Gallery. Photograph © Clay Perry, courtesy England & Co Gallery

In August 1966 Houédard participated in “Falling Event” at the invitation of the Japanese artist and Fluxus member Mieko Shiomi. “Falling Event”, to take place anytime between 24th June and 31st August, was the third in a series of nine events that she called Spatial Poems. Each one began with an invitation to a large number of her Fluxus friends and Mail Art colleagues for them to respond to a simple instruction, which often took the form of an intimate action poem that any one could perform. The responses she received in the mail would then constitute the work.

SPATIAL POEM NO. 3

The phenomenon of a fall could be described as a segment of a movement towards the center of the earth. This very moment countless objects on the earth are taking part in this centripetal event.

SPATIAL POEM NO. 3 will be the record of your intentional effort to make something fall, occurring as it would simultaneously with all the countless and incessant falling events.

Please write to me how and when you performed it, as we are going to edit them chronologically.

You could participate as many times as you want until August 31, 1966.

Nam June Paik, La Monte Young, Allen Ginsberg, John Cage, Robert Filliou and Ian Hamilton Finlay were amongst the couple of hundred artists and poets that contributed to the event.

Each participant’s contribution was printed on a small card, with the date and time if known and the details of the event they performed, and then placed chronologically in a purpose-made wooden box. Shiomi’s own participation was recorded as having taken place on July 14, 11.45am:

The big letters “S”, “P”, “A”, “T”, “I”, “A”, “L”, “P”, “O”, “E”, “M”, each cut out from white cardboard were released from the top of Olympic Stadium in Jingu Park by several musicians. As it was a windy day, some letters flew into the stadium and some, after fluttering trips, finally fell on the forest in the park.

Mieko Shiomi perfoming ‘Direction Event’ at the Washington Art Gallery, New York, in 1965

However, some of the actions were far more easily performable. Allen Ginsberg, in San Francisco, shaking a “small cloud of white salt on the floor”, or John Cage, in North Carolina, dropping answered correspondence into his fireplace.

Houédard responded to Shiomi’s instructions by writing a score for a “joint participation” with John Cage. His contribution, “c-dagesh”, is a seven-note suite that engages theologically with the instructions for this “centripetal” movement, as outlined by Shiomi. Characteristic of Houédard’s concrete poetry, the suite explores the potential metaphors and meanings revealed in an etymological contemplation of the words of the instructions themselves, seeing each word as having a zip that could be undone to reveal itself. Houédard is particularly drawn to Shiomi’s use of the word centripetal, from the Latin centrum (“centre”) and petere (“to seek”). If Shiomi is interested in the idea that in each staged or unstaged fall, objects are drawn by gravity towards the earth’s centre, then Houédard plays with this concept further. Objects are – to use one of his favourite palindromes – d-r-a-w-n-i-n-w-a-r-d: a journey from a visible external world towards an invisible internal centre.

The title of the piece “c-dagesh” is composed of the letters d, s, h as Houédard signed all his poems and art work, and the letters that spell out c, a, g, e as in [John] Cage.

But these letters have another meaning too. As Houédard outlines in his notes to this piece:

“dagesh”: name for the point or dot in the bosom of 6 letters in the Hebrew alphabet b-g-d-k-f. […] Also “the word-root d-g-sh is from the verb dagesh to pierce with a sharp point like a pen-tip”.

Therefore implicit in these instructions there is the suggestion that the suite will somehow pierce our expectations, our understanding of things, or complacency of seeing. It will unzip our expectations of reality to enable us to seek the centre of things.

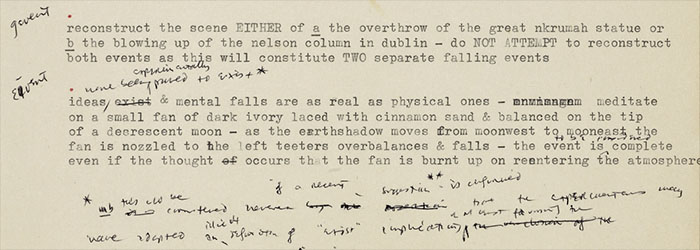

Each of the seven notes – cevent; devent; avent; gevent; event; sevent; hevent – are about contemplation, distraction and the propulsion of an inner journey towards an inner nothingness. Throughout the suite, various bodies – particles of dust, a flat sheet of poly(methyl-methacrylate), the great Nkrumah statue, Nelson’s Column in Dublin , a small fan of dark ivory laced with cinnamon sand, a single bead of quicksilver, pieces of paper – are “consciously” and “musically” united “to the universal pluritotality of falling events” that draw all these bodies along a circular path towards the centre of things. The term “pluritotality”, a coinage by Houédard himself, is an apt word that attempts to name what he describes as the “actual-links & even possible-links between the eastern and western” spiritual and philosophical traditions the movements in these ‘notes’ tease out.

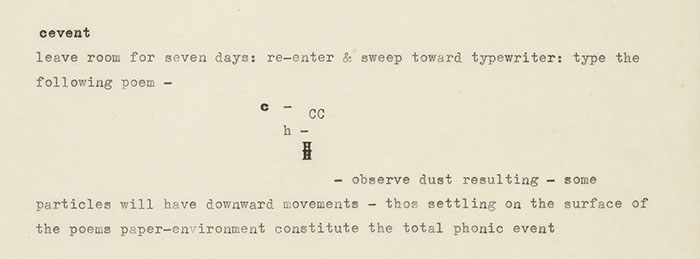

We can explore these ideas further if we look at “cevent”, which is the first note in the suite:

Page from original typescript, now in the John Rylands Library. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Prinknash Abbey Trustees, Manchester

The first instruction, to leave the room for seven days, has both subtle and obvious connotations. Seven, of course, references the biblical seven-day creation, seven days in the week, the seven notes of a heptatonic scale. Like Houédard’s interest in the root of the word dagesh, here we are directed to the root of the scale, C, which very deliberately roots us firmly in traditional Western music. But here we leave Western tradition behind, as the instrument that plays notes from this C scale is a typewriter.

The typewriter transforms into an instrument that produces an alternative scale of seven notes in the use of the keys c, C, h, H,–, shift and the space bar.

Who plays the typewriter? Initially Houédard perhaps, or Houédard and Cage simultaneously at an appointed time during the month of August. But this is a score readily available to anyone with a typewriter, and in 1966 this was of course an everyday object found in most places or work and many homes. The notes of the typewriter keys would be a mundane, familiar, almost background noise to many people’s lives. However here, in “cevent”, we, the audience are being directed to listen to this noise with the attentiveness that we would approach a traditional Western orchestral composition. The c key, the space bar key, the space bar key…

Who plays the typewriter? Initially Houédard perhaps, or Houédard and Cage simultaneously at an appointed time during the month of August. But this is a score readily available to anyone with a typewriter, and in 1966 this was of course an everyday object found in most places or work and many homes. The notes of the typewriter keys would be a mundane, familiar, almost background noise to many people’s lives. However here, in “cevent”, we, the audience are being directed to listen to this noise with the attentiveness that we would approach a traditional Western orchestral composition. The c key, the space bar key, the space bar key…

But before we even hear or play this composition on the typewriter, we re-enter the space where it has been left untouched for seven days and sweep towards the instrument in situ.

Here the piece enters what could be termed a “dialogue zone” with Mahayana Buddhism (a term coined by Ana Christina Lopes to cover the complicated and inter-related use of the Mahayana Buddhisms of Zen and the Vajrayana in post-war Western culture). The very act of sweeping recalls the Zen phrase “before enlightenment sweeping and chopping wood; after enlightenment sweeping and chopping wood” and also the tale of Lam Chung, the Tibetan Monk, who, according to the Lam rim teachings, gained profound insight and realisations into the true nature of existence through the simple daily devotional act of sweeping the temple. Characteristic of many of the Fluxus scores, these acts of sweeping (and then typing) negotiate the intermedia between daily life and art.

After the sweeping and the typing, we are however alerted to the fact that it is not just the sound of the typewriter keys being struck that we should listen to; instead it is the observation and attendant listening to the particles of dust as they fall onto the paper-environment that “constitute the total phonic event”. How do we hear the inaudible sound of dust falling? It requires a very special kind of listening.

It is in his artwork, particularly works like “c-dagesh” inviting our participation in a performance or an action, where I think Houédard is most successful in communicating his wider ecumenical vision and our shared experience in the being-ness at the centre of things. Just as the force of gravity pulls the dust motes downward to the centre of the earth, so too, in the act of contemplation, our mind is drawn-inwards to the heart centre and the centre of our own nothingness.

It does not matter whether we are Catholic, or Buddhist, or Muslim: the inner attentiveness required to hear dust falling is a common experience of the deepest contemplation. Crucially, it is an inner attentiveness necessary in the midst of our busy lives. Writing over twenty years later in the 1980s, in a series of talks to the Beshara school which his biographer Charles Verey describes as his most “complete, lucid and personal explanation of the meaning of his vision”, Houédard states:

It is the awareness of God’s presence in everything we do, whether we are washing up or going shopping.

He continues:

We merely have to realise the truth of our nature; the truth that we are perpetual eternal possibilities and this is true whatever we are doing. To be aware of that is the whole point of a seeker, that one’s mind is perpetually aware of the presence of God, the anamesis in Greek, this remembrance of God. What we remember of course is our own nothingness; we are aware of this whatever we are doing.

And he concludes that:

Not that it is easy but it does mean we do not have to do special things, though special things can help us. There are various techniques that can perhaps help novices to become aware of this but in normal life it is this perpetual remembrance which is ceaseless prayer, unending prayer, perpetual prayer.

I think “c-dagesh” is one such special thing. Interestingly most of these falls end in a destruction of sorts: dust settles and is disturbed on typewriter keys; the yogic practitioner of the tittibhasana pose totters and falls; the joints of polymethylmethacrylate whiten and fail due to outdoor exposure; Nelson’s Column in Dublin is blown up, etc.

Page from original typescript, now in the John Rylands Library. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Prinknash Abbey Trustees, Manchester

As we read this score, imaginary phenomena are created but also destroyed into a nothingness, an emptiness:

The […] journey is back to the world where, as St. Augustine says, words have beginnings and endings again. And on this journey, as the Tibetans put it rather neatly, we see all things without exception as mirrors of our own emptiness or perpetual becoming or nothingness. We see that all things, because it is only one creation, have this state of “emptiness” that is empty of self-being; all being is given and is not owned.

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner picture: “Cevent 2016” by Richard M. Simmons.

First Inset Image: Dom Sylvester Houédard at Prinknash Abbey. Courtesy of William Allen Word & Image.

Second Inset Image: Dom Sylvester’s Olivetti 22 typewriter. Photograph by Richard M Simmonds.

Dom Sylvester and Beshara (below): Swyre Farm. Photograph courtesy of the Beshara Trust.

Other Sources (click to open)

GUY BRETT: The Sixties Art Scene in London: The Third Text, 7:23, 1993, pp.121–3.

“Concrete Poetry and Ian Hamilton Finlay” in NICOLA SIMPSON [ed] Notes From The Cosmic Typewriter, The Life and Work of Dom Sylvester Houédard, Occasional Papers 2012, p.158.

For information on “Falling Event” see:

http://post.at.moma.org/content_items/195-spatial-poems-by-shiomi-mieko/media_collection_items/4703

http://artistsbooksandmultiples.blogspot.co.uk/2015/09/mieko-shiomi-spatial-poem-no-3-falling.html

http://artistsbooksandmultiples.blogspot.co.uk/2015/09/mieko-shiomi-spatial-poem-no-3-falling.html, date accessed: 10/06/16.

ANA CRISTINA LOPES: Tibetan Buddhism in Diaspora: Cultural Re-signification in Practice and Institutions, Routledge 2014, p.88.

DOM SYLVESTER HOUÉDARD: Commentaries on Meister Eckhart Sermons, Roxburgh: Beshara Publications, 2000, pp.3; 86–7; 12.

Our thanks to Richard Simmons for creating the original photographs used in this article; to England and Co, and William Allen Word & Image, for allowing us to use images from their collections, and to the Trustees of Prinknash Abbey for their permission to reproduce Dom Sylvester’s typescripts.

Dom Sylvester and Beshara

Dom Sylvester and Beshara

Between 1974 and 1991, Dom Sylvester was a regular visitor to the Beshara School at its various locations in the UK – Swyre Farm (pictured, left), Sherborne House, Frilford Grange and Chisholme House [/]. Widely known as “the Dom” by Beshara students, he felt comfortable in the environment of the school, where he was able to develop his ideas freely without the lingering shadow of dogma or doctrine. Some of them have been published in Commentaries on Meister Eckhart Sermons [/] (Beshara Publications, Roxburgh, 2000) and one, Questions about Questions, in the first issue of Beshara Magazine (Issue 1, 1987). A collection of the nine remaining talks is currently being prepared by Charles Verey and Jane Clark under the title The Kiss; Beshara Talks 1986–1991, and is due to be published by Beshara Publications [/] in 2019.

Nicola Simpson is a curator and researcher who has specialised in the art of mid-20th century Britain. She is the editor of Notes from the Cosmic Typewriter, The Life and Work of Dom Sylvester Houédard (Occasional Papers, 2012). She was also curator of an exhibition Performing No Thingness which featured the work of Dom Sylvester Houédard, Kenelm Cox and Li Yuan Chia, at Norwich University in 2016

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments