Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 17, 2020

Maintaining a Radical Edge

Dharmacharini Suryagupta, Chair of the London Buddhist Centre, talks about the transformative power of Buddhism in the contemporary world

Maintaining a Radical Edge

Dharmacharini Suryagupta, Chair of the London Buddhist Centre, talks about the transformative power of Buddhism in the contemporary world

The London Buddhist Centre [/] is one of the oldest Buddhist organisations in the UK, founded more than 40 years ago. Now housed in a beautiful restored fire station in Bethnal Green, it attracts a large and lively multicultural audience to its many talks, meditation sessions and retreats. When the Covid-19 pandemic forced it to close in March, it set up a digital platform and now has thousands of people all over the world participating in online meditation and home retreats. In this interview, the current Chair, Suryagupta, talks to Jane Clark about Buddhism’s potential to transform both ourselves and the society we live in, and her own interest, as a trained lawyer and social worker, in social justice movements.

Jane: The London Buddhist Centre is a stand-alone organisation, but it is also part of the Triratna Buddhist tradition. How does that work?

Jane: The London Buddhist Centre is a stand-alone organisation, but it is also part of the Triratna Buddhist tradition. How does that work?

Suryagupta: Triratna works through a series of centres and charitable organisations which are all autonomous but who share the same Buddhist vision and practices. The London Buddhist Centre is the largest in the UK – maybe even in Europe. Triratna centres are quite different in that they all have their own particular cultures and histories, but the common aspect is the teachings that we follow.

Jane: The name ‘triratna’ itself is a very traditional one, as I understand it. It means ‘three jewels’ in Sanskrit, referring to the three aspects of Buddhist practice: the Buddha; the dharma, which is the teaching; and the sangha, meaning the spiritual community. But as a movement, Triratna is a specifically Western form of Buddhism.

Suryagupta: The founder was Sangharakshita [/], who was an Englishman. He went to India whilst he was in the army during the Second World War and stayed on afterwards. He felt that he was a Buddhist – in fact he had felt that since a very early age – and decided that he wanted to live the life of a monk, and in particular wanted to follow in the footsteps of the Buddha. He did exactly what he understood the Buddha to have done: he got rid of his passport, thereby letting go of his civil identity, donned the robes of a monk and spent twenty plus years in India studying under an array of different teachers – Indian, Chinese, Japanese Zen masters. He was there during the Chinese invasion of Tibet, so he was also able to meet a lot of the Tibetan masters who came to India as exiles at that time.

As a result of all that, he came to see that there was a commonality between all the different Buddhist schools. So, when he finally returned to England in the 1960s he decided to found a movement that drew together the fundamental teachings from various traditions into an approach that would be relevant and accessible to westerners. This was partly because many of the other schools had naturally come to practice Buddhism according to the culture they are in – Tibetan, Indian, Chinese, Japanese, etc. – and he felt that this is a correct process. Wherever Buddhism goes, it needs to draw from its cultural context – or rather, contexts, because in the UK, of course, we are ethnically and culturally diverse. At the time, Buddhism had not landed properly in the West, so he was one of the first people to set up an approach that honoured the Buddhist tradition but adapted it to the cultural context of the UK and beyond.

He also believed that the practice of Buddhism needs to let go of some of the things which no longer speak to a contemporary audience. And this is not just a matter of culture; he felt that Buddhism worldwide needs to adapt to current conditions. For example, it used to be central to monastic practice to go door to door with an alms bowl collecting for food, and to only eat once a day. If you are a very strict monk or nun you can still practice this in some countries. But for most people in the West – or contemporary people worldwide – it is simply impractical.

Jane: We published an article a few years ago about the Tibetan Buddhist, Akong Rinpoche of the Kagyu tradition, who founded the Samye-Ling monastery in Scotland. They have gone through a rather similar process.

Suryagupta: Yes I think that most of the Western Buddhist traditions have had to adapt – in fact, they have been forced to adapt. People come to you with particular issues which require a response, and it happens quite naturally that you start to address them in ways that they can relate to.

The London Buddhist Centre. The building is a Grade II listed former fire station which has been lovingly restored after it fell into disrepair and was gifted to the centre by Tower Hamlets Council. Photograph: Robert Scarth via Wikimedia Commons

A Radical Edge

.

Jane: What is striking about Triratna is how successful it has been, inasmuch as a great many people participate at some level in the centres and the practices. I have read that there are about 300 centres worldwide and about 100,000 people who are currently involved.

Suryagupta: It is hard to talk about numbers because, as I said, each centre is autonomous. But certainly at the London Centre, which has a very distinctive culture, before Covid we had hundreds and hundreds of people coming each week, and now that we have gone online, we get about 1000 or 1500 people signing up to our retreats.

But what I would emphasise is not the number of people involved, but the aspect of community, which is very important in Triratna. Although our centres are autonomous, the community as a whole has developed very strong roots over the years and we have network which stretches across countries and continents. I call it a network of friendship. We all know each other well: people sometimes live together – we have several residential communities – and work together both within and without the actual centres. So whilst there is a strong emphasis on individual practice, there is also an aspect of collective life and work.

Jane: It is very noticeable at both the centre and in the online meetings, that, unlike many other spiritual groups, there are a lot of young people involved. What is it, do you think, that draws them?

Suryagupta: I think that people come for many different reasons. Triratna actually started off with a lot of young people. The 1960s were a very idealistic time, a time of great change, so it drew a group who were interested in radical transformation. But then it went through a period of growth and establishing itself. People grew up and matured, as they do, and there was a point when it was not attracting younger people; it was attracting people who were like the people who were running things – mature, middle-class and on the whole white.

But at the London Centre in particular we have always wanted to keep what you might call a ‘radical edge’. It is actually very easy for Buddhism to become a pleasant addition to the rest of your life – you might go to meditation in the same way as you might go the gym or on holiday, to top up on something that you feel you need a bit of. That is fine, but in order for Buddhism to really have a deeply transformative effect, both on the individual and on the world, we felt that it was important to retain a radical aspect to what we do. So we have continued to maintain residential communities where people live together; we have continued to run businesses – not as many as we used to, but still some – and over the last ten years we made a particular effort to attract young people.

Jane: Why are they of special importance?

Suryagupta: Young people today still have a bit of freedom to decide what they want to do and how they want to live their lives. They don’t have as much freedom as people did in the 1960s, or even as I did when I was younger, but they are still not all tied down with mortgages, or long-established careers. So we have been very keen to keep alive the idea that deep transformation is possible. Buddhism can help you to de-stress and find relaxation – and we do run yoga and Tai Chi classes at the Centre, and stress-reduction classes. But it can also be something that helps you move towards enlightenment – towards real liberation. And in order to feel that – to taste that – you need to be with other people of all ages and of all cultures who are on that path.

We are not just concerned to attract young people; we want to bring in people of colour, people from a range of socio-economic backgrounds. For me, Buddhism really is for everybody and there will be some people from all walks of life who want to really change their lives.

Suryagupta addressing a meeting in the Shrine Room at the London Buddhist Centre. Photograph: courtesy of London Buddhist Centre

Transformative Practice

.

Jane: When you talk about maintaining ‘a radical edge’, what does this involve? Most people would interpret ‘radical’ as meaning something political but this is not the sense in which you mean it.

Suryagupta: No, not at all. I can perhaps explain by starting from the fact that we are very conditioned beings. As we grow up, we are told that we have to get a job, find a partner, raise a family – that we need to be comfortable and secure. All that is fine – I have a family myself – but none of these things by themselves give you freedom. By freedom, I mean freedom from the core things that cause suffering, which we would describe as greed, hatred and ignorance. So by radical, I mean a perspective which believes that it really is possible to uproot those core mindsets and live and relate to the world from a basis of love and wisdom. That has all kind of implications for how we interact with others and our environment.

Jane: You concentrate within Triratna on two basic practices: the mindfulness of breathing and the cultivation of loving-kindness – the metta bhavana. How do these help people move towards this kind of transformation?

Suryagupta: Mindfulness of breathing, as you probably know, is a practice which pre-dates Buddhism. The Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, was taught the practice by his own teachers, and in some ways it is a very simple technique. You really just have to follow your breath, and in itself this produces calm, relaxation, concentration and integration. But the Buddhist framework, which the Buddha gave it after he had achieved enlightenment, is very much around the idea of impermanence – the fact that everything is in process, everything changes. It is an essential part of Buddhism to try to live by that truth.

And it is in some ways a very difficult truth to live by. One can know it intellectually – everyone knows it intellectually, even a small child does – but we don’t actually know it emotionally. If we did, when difficult things happen – like we break a mug, or the car breaks down, or we lose someone we love – we would be able to be with that experience without the degree of suffering that we normally go through. So impermanence is one of the central messages that the Buddha taught, and following the breath, which is constantly changing, just as our thoughts and feelings are constantly changing, starts to tune us into that truth.

Statue of the Buddha in the courtyard of the Vajrasana Retreat Centre [/], a new architect-designed facility in the midst of the Suffolk countryside where the London Buddhist Centre organises retreats. Photograph: picuki.com

Love and Compassion

.

Jane: And the loving kindness practice – the metta bhavana?

Suryagupta: This is a specifically Buddhist practice – in fact, the Buddha devised it himself – and he taught it knowing that it is the practice we need in order to transform our own suffering. And in the end, this is what we all want to do. We all have a deep desire to be happy. So the metta bhavana helps us to get in touch with the core experiences of how we relate both to ourselves and to other people. This is usually the cause of our suffering; we have a row with someone, we get annoyed, we get jealous, we feel insecure or we are competitive, and all of these things make us unhappy. This happens both on an individual level and at a collective level. Countries are also like this, which is why we get all kinds of conflict.

So the metta bhavana is a way of cultivating a response to others which is aware, and also ethical and loving. The fundamental truth which lies behind the practice is that we are all deeply interconnected – your happiness affects me, just as your suffering affects me. We don’t see this in our normal everyday lives. We see ourselves as isolated, separate individuals who can just do our own thing without consequences. If we really understood how interconnected we are, we would naturally want to care for others, and for ourselves.

Jane: There is an economic concept now called ‘Abuntu Rationality’ which recognises that our well-being is deeply connected to everyone else’s well-being, so it is in our own self-interest to care for the welfare of others.

Suryagupta: Exactly. But we cannot come to this realisation intellectually, although we can reflect upon it and think about it. When Covid happened, I thought that there were moments when we all really felt that. We felt thankful to the people who were delivering things and collecting waste, and had the realisation that we would not be able to live our lives without them doing what they do. I felt that for a short time we had a kind of collective awakening. But now we have gone back into our normal boxes.

At its simplest level, the metta bhavana is about recognising our common humanity. We are all human beings with the same fundamental problems. We share a common narrative in that we come into the world and spend most of our time trying to figure it out, often focussed on how to get what we want, avoid what we don’t want and find some sort of security and love in the process. We all share this search and experience some suffering in the process. Meditation and the teachings help us gain insight into all of this and free ourselves from the suffering involved.

Jane: One of the things I really like about the practice is that you can track your progress. You can suddenly notice, for instance, that you are less irritated by someone.

Suryagupta: Yes. When I first started practicing, I really wanted to work on being kinder to people, so I had a little practice of giving up my seat to people on the tube if they looked like they really needed it rather than just burying my head in a book. And it was an effort, because sometimes I did not want to do it and I would find myself rather harshly evaluating whether people were really deserving of my seat. But after a while – I must confess it might have been several years! – I found that one day I just did it without even thinking about it. And since then, it has been a joy to give someone my seat.

I know this is a very simple example, but there is this aspect of Buddhism where you can see very directly the effect it has upon your everyday life and relationships. You can approach a religious tradition at many different levels – intellectually, philosophically – but doing a practice like the metta bhavana inevitably brings you up against yourself. You are faced with real life choices.

Jane: Buddhism normally talks more about compassion than about love, but you in particular tend to use the word love, loving-kindness, etc.

Suryagupta: The word we use for compassion is actually quite a complex one. From a Buddhist perspective, you don’t really know compassion until you have reached a state where you see through the delusion of separation between you and others. Part of our suffering results from the fact that we experience ourselves as separate beings. But when we really know that we are interdependent, when someone else suffers, we naturally feel it. But because this is quite an evolved state, we don’t feel it as pain as such, but more that there is a sense of feeling with somebody else.

I think that when we hear the word compassion, we often understand it as wanting to help someone, and then there is a danger of being overwhelmed. So people get distressed because they witness all the suffering in the world. But how can someone who feels that they are just a separate individual handle that in a way that is actually potent? They are more likely to feel hopeless – that it is too much, that they cannot cope with it.

Jane: We talk about ‘compassion fatigue’.

Suryagupta: Yes. But that is not what compassion is. Compassion has wisdom at the heart of it – not only the understanding that we are not separate beings, but also the knowledge that we are tapped into a huge reservoir of love. So I talk more about love than compassion, I think, because of my understanding that we really need to be connected to this reservoir of love if we are to feel for other people. We need to be connected to it for ourselves – to feel that we are capable beings, and that we have a lot to give. And to do this, we need to let go of some kind of of self-centredness. In fact, I think it is true to say that whenever we love someone, in whatever way, we have let go of some kind of self-centredness.

Love is also a complex term, of course, with lots attached to it. But when I talk about it, I am referring to this deep feeling for oneself, and for the others, which I think we have all experienced at some time.

The Breathing Space room, where the Centre’s mindfulness and well-being activities take place. The mural is designed by local artist Aloka. Photograph: courtesy of London Buddhist Centre

Culture and Identity

.

Jane: You have a huge range of events taking place at the Centre each day – now mostly online of course: meditation groups, yoga and Tai Chi groups, art groups, poetry groups. You also have a number of groups where people can meet others with similar backgrounds or pre-occupations, such as people recovering from addiction, under 25s, people of colour. Why do we need these if the premise is that all human beings have basically the same problems?

Suryagupta: I think of them basically as groups for people with similar experiences. We have a group for carers, for instance, who have a different day-to-day life experience from people who are not carers. The addiction group is actually a mindfulness group which offers stress reduction, relaxation, etc. You don’t have to be a Buddhist to take part, and the same is true for groups for people with depression. They are just us offering support based on our own experience for people going through these difficult processes.

But we also have a history of offering Buddhist groups for people with particular kinds of experience. For years there was an LGBT group going, and we have had groups for people of colour for more than 30 years. This group has grown since Black Lives Matter [/] came to prominence earlier this year, but it is not a new thing for us. I have personally found this group very helpful. When I first became involved with Buddhism, I was attending another centre which is much smaller, and I was the only black person or person of colour there. I knew straight away that I would need to practice with other people of colour – as well as everybody else, of course. And that was because I came from a particular cultural heritage – I am African–Caribbean – and have had a certain experience of race and racism in this country.

I also really took on what Sangharakshita said about Buddhism having to connect with your own culture. I have a dual culture. I was born in London and so think of myself as British – and at the Centre we are very good at speaking in the language of the contemporary Western world. We talk about the arts, about science, about psychology, and we have a particular interest in poetry with the Poetry East group. But I also have my African roots, and there was a question about how I could integrate all of that. I knew if I did not also tackle this, certain parts of me might get left behind.

Jane: So this is not about having different practices, but just to discuss what is happening to you?

Suryagupta: Yes, seeing what we have in common and what is different to other people from similar backgrounds. And also feeling free to talk about our own experience, because when it comes to experiences of racism, it is normally only people who are visible racial minorities who have had direct experience of it. White people, who are in the majority in this country, don’t always understand it, or feel comfortable talking about it.

And we need to talk about such things, as in Buddhism we are always working with our own experience – meaning, that we are always looking at our own conditioning, whatever it is. If you come from a fantastically privileged background and a supportive family, that is your conditioning and you work with that If you come from a very dysfunctional background, or a very poor one, then that is your conditioning. So for me, it is important to be able to talk about race, racism and identity for my spiritual growth.

Our people of colour group is actually very diverse – we come from very different ethnic and cultural backgrounds – but we are all trying to relate our heritage to the mainstream European context. We talk about things like identity, migration, the effects of colonialism, cultural conditioning but also the positive aspects of having a dual heritage; how do we bring that in and enhance our practice so that we can be fully nourished and confident beings.

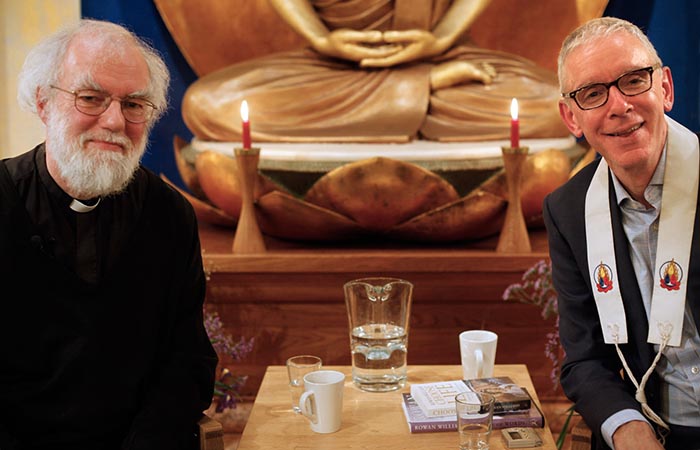

Dr Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury (left) talking about his work with Maitreyabandhu of the London Buddhist Centre (right) at a Poetry East event. Poetry East [/] organises monthly meetings which explore the meaning and value of the arts on the spiritual path. Photograph: Courtesy of the London Buddhist Centre

Becoming a Buddhist

.

Jane: Can you say a little bit about your own background? You have mentioned that you are of African–Caribbean origin but you were born in this country.

Suryagupta: My parents were of the Windrush generation [/] – that is, people from the Caribbean who emigrated to the UK in the mid-twentieth century. So they struggled, as many of that generation did, to establish themselves here. They sent me and my sister back to the Caribbean for my early years, and I came back here, to East London, when I was about six. I was actually on a search for something even then. I remember that I felt very disconnected when I came back, and recall having three thoughts. Firstly, I wanted to know why I was here, and how I got here, because I did not understand. Secondly, I felt that my birth name did not fit me. And thirdly, I wanted to find a place of beauty, because my immediate environment was poverty stricken and hostile. These three things started me off on my search.

Jane: When did you become involved in Buddhism?

Suryagupta: When I was at university. I went there to study law, as I had developed quite a strong sense of social justice as I was growing up. But I got rather disillusioned with law as a profession, as it seemed too materialistic and commercial, so I gave up the job I had been offered and went to work with community groups, and with refugees and asylum seekers. I then did a Masters at LSE in Social Policy and Social Work and became a social worker.

So Buddhism kind of accompanied me though my twenties, and once I had become ordained, my search was no longer about the question: what do I need to be happy? – not that I was totally happy, but I knew that I had the tools to work towards that. My question became: how can I give appropriately in a way which is of benefit both to myself and to the world? So that is where social work and community development came in. Later, after I had my son, I became a professional storyteller, which was a different way of giving which nourished me as well as others.

Jane: Can you say something about this process of becoming ordained. What does it mean in modern-day Britain?

Suryagupta: Ordination is really a way of getting behind our spiritual aspiration – getting ourselves aligned with it mentally, psychologically, emotionally. I sought ordination after about three years of being involved – that is, three years of meditation. You have to ask for it, and then there is a training process where you attend special courses and retreats, and come into contact with a lot of people who are deeply committed. Then there is a point at which you feel that you have done enough work – and other people also feel this – and you are invited to get ordained. It basically involves going on a special retreat and being given a new name, which is one which reflects your special qualities, or qualities you should be working on. Ordination connected me to the whole Buddhist tradition going all the way back to the Buddha, 2500 years ago.

Jane: And your name means…?

Suryagupta: It means ‘she who is protected or guarded by the sun’.

Jane: When you received it, did you feel that it was the name you had wanted when you were six years old?

Suryagupta: Yes, absolutely. I felt that I had finally got the right name! I love it because the sun has many different qualities: it is energy, it is warmth, it is clarity, it illuminates. It also has a connection to the Buddha, because when the Buddha was teaching, people used to say that it was like being in the sun because of the energy and warmth that he conveyed.

It is important to say that the name is also a teaching. When I first got it, I was astonished and loved it, but I also knew that sometimes I could feel like heavy clouds too! So it is there to constantly remind us of our qualities. As to the aspect of being protected or guarded, the sun is also like metta – it is one of the images we use in the meditation. So this means that the protection happens not through protectiveness or defensiveness but through loving kindness.

Jane: So being ordained does not mean that you have to live in a community or become celibate?

Suryagupta: No. When I was ordained, I was actually living in a community and was thinking that maybe I would go and live at a retreat centre, which would have meant a much simpler way of a life, maybe in another country or up a mountain somewhere. But about nine months later I got pregnant and had my son, so events dictated that my life went in a different direction and it turned out that next step after ordination was to be a mum.

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar with Dalit women delegates during the Conference of the Schedule Caste Federation in Nagpur, July 1942. Contributor: Historic Collection [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

Social Justice

.

Jane: So how do you reconcile your long-term commitment to social justice with your Buddhist practice? This is something that I often wonder about with the metta bhavana meditation, which cultivates love and acceptance of everyone regardless of their behaviour.

Suryagupta: This is a really relevant question in our present times, and it is a complex one. On the one hand we need to recognise that there is much more to this universe than we can see, and that in order to really understand life as a whole, we have to look inwards in order to understand the mind and the heart. On the other hand, there are people suffering right now – we are suffering – so what do we do about that? I think that this is the central challenge of being a Buddhist today. It has certainly been a core part of my life, and for the past three or four years I also worked on a programme at the London School of Economics supporting global activists.

Jane: So what special perspective do you bring to this?

Suryagupta: One of the things I can do as a Buddhist is to introduce a set of core values, so people can come back to a really strong value base when they are facing difficult situations. Otherwise, there is always the danger that in challenging someone’s behaviour, we tip over into hatred of them. We all have the tendency towards hatred and unawareness, and this can cloud our mind when we see something we don’t like. But Buddhism tells us that we can work towards changing something whilst still recognising a person’s essential worth and humanity – and we can still wish them well.

This is a much more empowered place for me. Nowadays I am much more able to engage with issues, have conversations with people about what I see as wrong, than I did when I was really angry at the world. This is because I am no longer coming from anger, but from a belief that we all fundamentally want the same thing but we just don’t understand enough about each other’s experience. The same goes for the ‘system’, which should be working for all equally but so often works for the powerful and privileged. How can we bring more awareness to that in both small and big ways?

Jane: Triratna is actually involved in a very large social justice movement in India, the Dalit Movement [/] – that is, working with people who were previously called ‘untouchables’.

Suryagupta: Yes, I myself have been very inspired by the work of Dr Ambedkar [/], who started the movement. He was born as an ‘untouchable’ himself, and although he was an eminent politician and the chief architect of the new Constitution of India after Independence, he was socially shunned by his Hindu colleagues because of his birth. He fought tirelessly for the rights of the Dalit community, who are still marginalised and discriminated against in India.

We are less engaged with social issues in this country, and I think we need to be doing more on the matters which are really to the fore now – climate change, issues around race, gender, the deep and increasing social and economic inequality which is a form of suffering for many people. I don’t think that everybody needs to be a champion in this; everyone finds their own way. For some Buddhists, their practice is very much to do with the arts; for others it is the psychological / therapeutic arena; and for some it is the realm of body awareness and well-being.

But what I think is important is that whatever sphere we are in, there will be people there from all walks of life, with all sorts of past experiences, and some of those experiences will have been impacted by social conditioning and challenges. We need to understand how we relate to differences we encounter and find appropriate ways to help all these people find happiness and fulfilment.

To find out more about the London Buddhist Centre, click here [/].

Walking meditation in the Stupa Courtyard at the Vajrasana Retreat, Suffolk. Architect: Walters and Cohen Ltd, 2016. Contributor: Dennis Gilbert-VIEW [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Suryagupta in the Shrine Room of the London Buddhist Centre. Photograph: courtesy of the author.

First Inset: The triratna symbol, indicating the ‘three jewels’ of the Buddhist path: the Buddha; the dharma or teaching; and the sangha, the spiritual community.

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Mindfulness Meditation – Alleviation of suffering for Neurological Conditions

Niels Detert, Consultant Neuropsychologist, explains how meditation can help people with long-term medical problems

Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

A visit to a new memorial which aims to heal a dark period of American history

READERS’ COMMENTS

Lovely article. The point that stayed with me was giving up ones seat. I was taught this as a child, and I taught my own kids to do this as well. It was a matter of respect for someone else, thinking of them as in more need, I guess than me. It was good manners to do this. I did it automatically and still do but Not sure if I do it for ‘joy’ but one does often get a lovely smile or thank you, which does make ones day. Now though when someone offers me their seat I wonder if I am just getting old! However I do not see it happen much on trains etc. What might we have lost by the loss of manners? Maybe not seeing people anymore just the crowd and ME. A conditioning of society involved with ourselves as separate from community and hence the lack of chances to be Human