Remarkable Lives _|_ Issue 15, 2020

Keith Critchlow: A Life Well Lived

Richard Twinch pays tribute to the teacher and sacred geometer,

who died on 8th April 2020

A Life Well Lived

Richard Twinch pays tribute to the teacher and geometer Keith Critchlow (1933–2020)

Professor Keith Critchlow (1933–2020) was a much-loved teacher and mentor to many of us at Beshara Magazine, as he was to so many others thoughout the world. His work on sacred geometry – deciphering the mysteries of megalithic circles, the movement of the planets, the structure of the great medieval cathedrals – opened up new and inspiring perspectives to those of us in the western world, and re-invigorated the artistic traditions of Islam at a time when they were in danger of being lost. In this article, his long-time student and colleague, Richard Twinch, pays tribute to an extraordinary man. We also present, at the end, the way that Keith described – and painted – himself: “I am an inveterate seeker of wisdom in all its manifestations…”

It is hard to remember a time when Keith – as Professor Keith Critchlow was known by royalty as well as the lowliest of his students – was not part of my life; he was instrumental in inspiring and sustaining it in so many ways. I was not alone. Hundreds, if not thousands, of people have had a similar experience and forged a personal relationship either with the man or with his work – or both, as the two were, and remain, inseparable.

It is hard to remember a time when Keith – as Professor Keith Critchlow was known by royalty as well as the lowliest of his students – was not part of my life; he was instrumental in inspiring and sustaining it in so many ways. I was not alone. Hundreds, if not thousands, of people have had a similar experience and forged a personal relationship either with the man or with his work – or both, as the two were, and remain, inseparable.

An artist, author, professor of both art and architecture, Keith was perhaps best known for his work on sacred geometry and as a visionary teacher. He leaves behind a hugely influential series of books – including The Order of Space, Islamic Patterns, Time Stands Still and The Hidden Language of Flowers – and the legacy of the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts [/] in Shoreditch, where a deep understanding of geometry, traditional skills and practices continues to imbue the students’ work with meaning and timeless beauty. He also helped found other institutions dedicated to the pursuit of wisdom, including, with John Michell, The Research into Lost Knowledge Organisation (RILKO [/]), Kairos, and in 1991, The Temenos Academy [/].

Keith had a close relationship with the Prince of Wales, conversing and travelling with him for over 30 years. He taught Princes William and Harry the art and science of geometry. I say ‘art and science’ because Keith had adopted early in his career the ‘traditional’ point of view that did not separate ‘art’ from ‘science’ but rather saw them as different points of view – complementary expressions – of the all-encompassing reality. Little wonder then that he dedicated his life to the circle – the symbol of wholeness – and the compass, which describes it from a single point and then elucidates it in the hands of a skilled geometer. This Keith definitely was, though humbly, he described himself just as a ‘pattern seeker’. He explained in a recent lecture for the Temenos Academy (see video right or below):

Geometry is at the root of the whole of manifestation. Whatever you call creation – whether you want to call it a ‘Big Bang’ or whatever – geometry had to be established for there to be ‘being’. […] Everything that we can turn our attention to is based on geometry, that is, the ‘order of space’. [1]

Video: The Art of the Ever-True. Duration: 32:29

The labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral. Keith’s pioneering work unlocked the meanings hidden within the geometry of the cathedral, as shown in his 1977 film Reflections [/]. [2] Photograph:Sonnet Sylvain/hemis.fr/Alamy Stock Photo

Early Years

.

Keith came from an artistic family and was educated at the famously experimental Summerhill School. He spent a short time in the RAF doing National Service, and as a youth he even had a trial as a goalkeeper for Chelsea Football Club! A footballing career would have been a loss to humanity, so fortunately for us he went on to St Martins School of Art to train as an artist – he was passionate about drawing and geometry in equal measure.

During the mid 1960s, Keith worked with the visionary engineer-architect Buckminster Fuller [/], famous for his work on geodesic domes. They met when he was giving a talk in London, after which Keith approached the great man and with a good deal of temerity, showed him some of the work he had done for what was to become his first book, Order in Space. ‘Bucky’ immediately recognised the enormous value of this, and he wrote a letter of recommendation to the Architectural Association (AA) in London:

Keith Critchlow has one of the century’s rare conceptual minds. He is continually inspired by the conceptioning of both earliest and latest record. He lauds the work of others while himself pouring forth, in great modesty, whole vista-filling new realizations of nature’s mathematical structuring. […] He is one of the most inspiring scholar-teachers I have had the privilege to know.[3]

Clearly the letter worked, as it launched Keith’s career in architecture. In 1966, he was given a lectureship at the AA, where he led what they called a ‘Unit’ – a self-contained teaching group gathered around a charismatic person who determined what their students would study. Keith was definitely charismatic, and remained so throughout his life. With his carefully selected team of tutors, he launched the career of many architects – including myself and several close friends. Perhaps the most famous were the engineer–architects David Marks and Julia Barfield who designed and built the astonishing London Eye and more recently the elegant and delightful Cambridge Central Mosque.

His lectures were a remarkable tour de force which would leave an audience transfixed. A twin Kodak carousel slide show, carefully assembled the night before to suit the particular group, would be beamed through the darkness and images would be unfolded one by one, while always keeping two juxtaposed images. “Next on the left, next on the right” would be intoned. (It never was quite so exciting in the computer age, which he adopted, reluctantly, in later life but was never at home with.) However varied the images, the narrative remained clear. The lectures nearly all started with the primary dot and the circle – but then rapidly contrasted microscopic images of embryos developing with the unfurling of the universes and geometric structures. Nearly always we ended up with Chartres Cathedral, which he visited with study groups many times over the years. As his student and colleague Jane Carroll has commentated, “It remained for him an example par excellence of the use of geometry to convey profound spiritual truths that are common to all the major religious traditions.” (For Jane’s article on Chartres, click here…)

Another student of this time, Dee Mitting, has reminded me of a further collaboration which resulted in him giving many talks to students at the Beshara School of Intensive Esoteric Education, then based at Chisholme House [/] in Scotland and Sherborne House in Gloucestershire. These interwove universal truths, fine details of geometric research and personal experience, sprinkled with a mischievous humour and occasional jabs at the state of the political world.

Islamic tiling in the Mexuar inside the Nasrid Palace in the Alhambra in Granada Spain. This was another building, alongside Chartres, that Keith visited again and again over the years. Photograph: db images/Alamy Stock Photo

Reviving the Traditional Arts

.

But Keith was not just a charismatic teacher. His geometric studies and inspiration had resulted in a deeper understanding of the underlying principles of order that lie within nature and ourselves. Order in Space – a design source book [3] published in 1969, turned out to be a seminal work which remains, 50 years later, the book everybody should read to understand the interrelationships of the Platonic and Archimedian solids as well as the two-dimensional geometries that underpin them. It is filled with ideas and established a context for the solids in the form of a ‘periodic table’. It also ties them back into the human in terms of scale and proportion that Keith had studied early in his career: “Geometry is done by a human hand attached to a human heart”, he maintained. Keith understood that reality is multi-layered as well as many-faceted – and he had a ‘shamanic’ skill in moving seamlessly between the ‘layers’.

His universal vision of humankind, mastery of geometry and the Platonic ideas, allowed him to move freely between different religions. He made friends with monks, priests, gurus and imams equally. He often quoted Socrates’ saying that “geometry is the art of the ever-true”, meaning, that it is true for all time and for all people. Keith understood intuitively that the same tools that could unlock the secrets of Chartres could also be applied to Buddhist and Hindu temples, Neolithic stone circles, and Islamic mosques.

Islamic patterns in particular caught his attention as being the most highly developed geometric expressions ever made. With his natural curiosity and boundless energy, he threw himself into the task of unravelling some of their secrets. The result was his second seminal work in a decade, Islamic Patterns [4] published in 1976. By this time, he was also teaching at the Royal College of Art, where he was Professor of Islamic Art until 1990. It was there, in 1984, that he and his friend and collaborator Paul Marchant founded a small department called VITA – Visual Islamic and Traditional Arts [/]. Here MA students could study Islamic geometry in depth and learn to apply it to their work in painting, textiles or sculpture – or more generally, perhaps, allow the sensibility generated through the study of geometry to penetrate their ways of seeing and doing. The process was transformational both for the individuals and the work they produced.

Islamic patterns in particular caught his attention as being the most highly developed geometric expressions ever made. With his natural curiosity and boundless energy, he threw himself into the task of unravelling some of their secrets. The result was his second seminal work in a decade, Islamic Patterns [4] published in 1976. By this time, he was also teaching at the Royal College of Art, where he was Professor of Islamic Art until 1990. It was there, in 1984, that he and his friend and collaborator Paul Marchant founded a small department called VITA – Visual Islamic and Traditional Arts [/]. Here MA students could study Islamic geometry in depth and learn to apply it to their work in painting, textiles or sculpture – or more generally, perhaps, allow the sensibility generated through the study of geometry to penetrate their ways of seeing and doing. The process was transformational both for the individuals and the work they produced.

The Minbar in the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem, which was reconstructed using Keith’s geometric analysis. Photograph: World History Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

The Prince’s School

.

It was also in 1984 that Prince Charles began his campaign against inappropriate architecture in what became know as his ‘monstrous carbuncle’ speech. This eventually led him to meet Keith. The Prince wanted to establish a School of Architecture where the principles of geometric harmony were taught, and Keith was clearly the man to do it. Prince Charles was also developing an interest in Islam. The Prince’s School of Architecture was started in 1992 and during the first year the transition of the VITA Unit to the School of Architecture was accomplished. This required enormous diplomatic skill as well as political awareness and Keith was not found wanting in either respect. He learnt that, as Director of Research, he needed to put on his suit, polish his shoes (as he had learnt in the RAF) and fight his corner – which he did.

The VITA department was subsequently transferred to a new Prince’s Foundation now known as PSTA – the Prince’s School of Traditional Arts [/] – but essentially it is still continues with the work it was doing in 1984, staffed largely by its former alumni and others who had been carefully ‘collected’ from the early AA days onwards.

Broadcaster Ian Skelley, a long time friends of Keith’s, has recounted a beautiful example of the influence that his work, and that of VITA, has had within the Islamic world – the reconstruction of the minbar (pulpit) of the al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem.[5] This was one of the wonders of the Islamic world, designed and constructed by a craftsman from Aleppo at the time of Saladin in the 12th century without nails or glue to bind it together. It had been fire bombed to almost total destruction in 1969 by a terrorist attack. The secrets of how to reconstruct it were seemingly lost and for twelve years, a call from King Hussein of Jordan for craftsmen to rebuild it went unanswered.

However Minwer el-Meheid, an engineer, came across a copy of Islamic Patterns in a backstreet in Cairo and recognised that this showed the geometry around which a reconstruction could be made. He made his way to London, met Keith at the PSTA and studied intensely, simultaneously building up a team of craftsmen and artists in Jordan to examine the fragments of wood that remained in order to work out how it was constructed. The collaboration between geometry and craftsmanship, between West and East, resulted in this famous work being recreated as it had been built in the first place.

The dining hall at the Krishnamurti Centre in Brockwood Park, UK

Architectural Work

.

Keith’s work on Islamic Patterns also brought him into contact with Seyyed Hossein Nasr [/] who wrote the foreword to the book. Professor Nasr is one of the foremost scholars of Sufism and had founded in 1974 what is now known as the Institute for Research in Philosophy, then under the aegis of Farah Pahlavi, the Empress of Iran. Keith was appointed to design a small mosque for the Aryamehr University in Tehran, and worked on the drawings in the little dome at the end of his garden in Stockwell. I was lucky to be his assistant, working up the drawings on a table in his dining room whilst the other assistant, Richard Waddington (also a former Cambridge and AA student) was out in Iran. This time gave me an insight into Keith’s close family life, and in particular the constant support of his wife Gail and later that of all his children. Unfortunately, the mosque was not to be; the politics turned sour and the Shah was subsequently deposed.

Keith’s architectural career was not of the ordinary variety; he had the ability to perceive wholeness and the geometric skill to describe that wholeness in space, which he saw as the expression of the soul of the building. This ability was first recognised by ‘Bucky’, and was later discerned by Jiddu Krishnamurti, the Indian writer-philosopher, who commissioned him to design a new study centre at Brockwood Park in the UK. The inspiration for this building – which was essentially a memorial to Krishnamurti, who died before it was completed in 1986 – was of a figure sitting cross-legged looking at the landscape, combined with phrase ‘The world is you, and you are the world’. (See video right or below and my article in the original print version of Beshara Magazine [/].)

Video: Harmony, Eternal Truths and the Krishnamurti Centre. Duration: 27:11

A less well-told story is that of the design and construction of the magnificent Sri Sathya Sai Super Speciality Hospital [/], Puttaparthi, A.P., India in 1989–90. The client on this occasion was the flamboyant Isaac Tigrett, who commissioned Keith (and a team of engineers and architects) to design the hospital that Tigrett was organising, having donated a large part of the proceeds of the sale of his European Hard Rock Empire to the scheme.

Jon Allen, the project architect on both the Hospital and Brockwood Park, described to me how Isaac found Keith in London and persuaded him to accompany him to Bangalore in India. Keith began his design by drawing the main elevation of what was to become, within little over a year, a 300-bed working hospital – and, though it changed radically as it was constructed (subsequently without the European team), it is this elevation that has remained closest to the original intention.

The new Cambridge Central Mosque; the Islamic gardens, the font and the front portico. The ‘breath of compassion’ geometry seen on the entrance pillars continues in the interior. Photograph: Morley von Sternberg

There were other smaller projects over the years – the Lindisfarne Chapel [/] in Colorado, for instance. The last, and perhaps most beautiful, of the buildings that Keith gave advice on is the new Cambridge Central Mosque which opened in 2019. This was designed by the late David Marks and Julia Barfield, who had been some of the first of his students at the Architectural Association and lived round the corner from him in London from early days. The mosque’s garden, unusually at the entrance rather than within, was designed by Emma Clark – another of his VITA students from the Royal College of Art and a close friend and collaborator at the Prince’s School for many years. The building is therefore the culmination of a collaborative effort that started almost 60 years earlier. At the commencement of the Prince’s School in 1993, which coincided with Keith’s 6oth birthday, he commented that for him this was the result of the second cycle of Saturn (each one lasts for 27–30 years). So this further cycle, finishing when he was 87, would not have been lost on him!

Keith advised from the very early stages of the building (see the short video right or below where he talks about his input) as well as providing geometry for windows and the mihrab (prayer niche), which awaits completion. To quote from the RIBA Journal in July 2019:

An underlying geometry, ‘the breath of compassion’ which is rooted in the Islamic tradition, has been designed by Keith Critchlow, an expert in sacred geometric art. This geometry, signifying the universal and the sacred, infuses the building from the plan to the brick bonding patterns, from the atrium floor tiling to the door marquetry. This is not about copying, Marks pointed out, but inventing anew.[6]

Video: Cambridge Mosque Geometer Keith Critchlow. Duration: 5:24

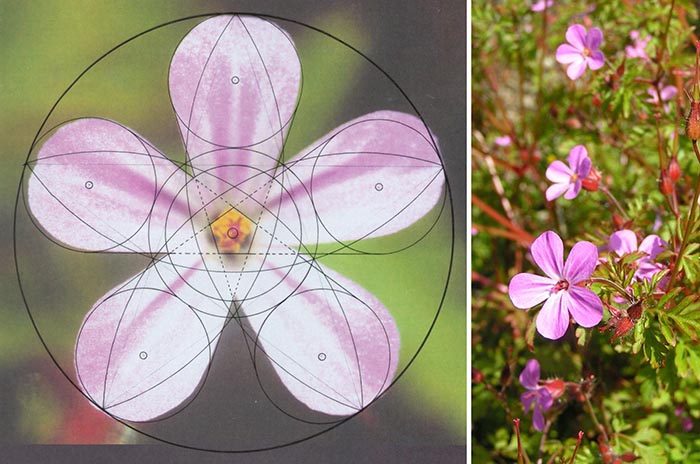

The Herb Robert showing its five-fold symmetry. This tiny flower was one of Keith’s favourites: “its very modesty and unusually powerful symmetry means it stands out in any garden context”, he wrote. From The Hidden Geometry of Flowers, p. 224

The Geometry of Nature

.

In 2003, Keith had the wisdom to pass the role of Director of VITA in 2003 to Dr Khaled Azzam, although he remained Professor Emeritus until his death. His retirement left time for him to return to writing, and in 2011 he published his third seminal work, The Hidden Geometry of Flowers, [7] which is a wonderful exploration of beauty and geometry in nature. Each study, made carefully with compasses, is a profound contemplation.

Ian Skelly in the recent Radio 4 broadcast Last Word [/] remarked that: “… until Keith brought it out, no-one had understood that the principles we see in traditional architectures also underpin the natural world”.[8] I am not sure this is totally true, as those who designed and built the great traditional buildings were surely not unaware of the connection. But it is certainly the case that in the Western world, Keith was one of the first people able to clearly demonstrate how the geometry we find in nature informs the design of traditional art and architecture and provides artists and designers with the tools to engage in this natural creative process. He said:

The biggest tragedy of nature is that everything is revealed to us, but we can’t see it because we are told – and education usually seals this up – to look for something else. We are taught to look at it as something different from what it is. But one of the most beautiful things is that when you have things revealed to you, this has an overwhelming effect upon your inner being; you can see how a flower works, how a plant works, even how an animal works. It gets through to your soul, and your soul is the most important part of you. Your body is only an expression of the soul, and the soul is only an expression of the spirit.[1]

The Prince of Wales speaks with artist Dana Awartani as he looks at her artwork during a visit to The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts Degree Show in London. Photographer: Lewis Whyld /Alamy Stock Photo

The Legacy

.

So what of Keith’s legacy? He leaves behind a wonderful selection of written work which continues to inspire younger generations. And he helped establish important institutions; VITA and later the Prince’s School of Traditional Art, has expanded widely, not only into the Islamic world – where it is reviving the original traditions, not so much by copying but, as David Marks rightly indicated, by returning to the origin, the root of the tradition – but also into other traditions such as those of Eastern Europe, India and the Far East.

The Temenos Academy is another great institution which he co-founded with Kathleen Raine, Brian Keeble and Phillip Sherard. This continues to thrive and educate along traditional principles, in particular those of the Platonic world. Keith also formed Kairos, an educational charity which investigates, studies, and promotes traditional values in art and science and publishes many of his smaller works. And much more; within my own sphere, he was a Honorary Fellow of the Muhyddin Ibn ʿArabi Society, whose aim is to open up the wisdom of this great mystic to Western seekers.

But perhaps the most important legacy is the huge body of students who have been educated either directly by Keith and/or in one of the institutions he helped establish. Like the candle that is lit at the start of each Temenos session, he was able to create the spark that kindles the imagination which lights truth, beauty and goodness in so many hearts. This is what persists in the human soul when the buildings crumble and the books themselves get lost in the mists of time.

This was indeed a life well lived.

Thank you Keith.

Keith on Himself

Keith’s self-portrait, submitted to the ‘Face to Face’ exhibition at King’s Place, London in 2011

In 2011, Liz Gray asked 99 people: “If you had breath for no more than 99 words, what would they be?” This is the answer that Keith gave, plus the biography he submitted for the book which ensued.[9] You can hear him reading his 99 words and commenting upon them in this short podcast (duration 7:09).

99 Words

Love, compassion, kindness, interdependence, truth,

goodness Beauty, Harmony integrity integrality

forbearance, patience, understanding, light,

rain flowers trees soil birds, animals insects

people togetherness, unity, sound, music orchestration

dance, walking talking thinking pondering concentrating

sameness otherness health happiness breath water

air earth and sunlight moonlight, stars rainbow

mountains lakes rivers birdsong prayer meditation

“More than you need will always be greed.”

Silence quietness peace inspiration bliss, work

diligence craft application agreement, writing

singing painting drawing composing digging

gardening, food vegetables fruit nuts seeds

communicating carefully. Life, looking seeing

understanding teaching making drawing reading

arranging cooking eating, bathing relieving

Family. Peace.

Biography

.

I am an inveterate seeker of wisdom in all its manifestations. I teach, paint, design and write to the best of my ability. I value the special few friends I have who are concerned with the same goals as myself. I have a wonderful wife and family, all of whom I am proud of. We live modestly and value our neighbours. (enough)

Richard Twinch MA (Cantab) AA Dipl RIBA trained as an architect at Cambridge University (1969–73) and the Architectural Association (74–76). He was External Examiner to the VITA Department at the Royal College of Art in 1989 and a tutor in 1992. He was a senior lecturer at the Prince of Wales’ Institute of Architecture 1992–94 and a tutor at Oxford Brooke’s University 1994-98. He was the External Assessor for the University of Wales for the first VITA quinquenial review. He practiced architecture in Oxford 1997–2015 . He is currently the Events Coordinator and a Trustee for the Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi Society CIO, UK

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Keith with a pair of compasses presented to him by the Muhiyyidin Ibn ʿArabi Society on his 80th birthday in 2013. Keith was an honorary fellow of the Society from its inception in 1977. The compasses were made by David Apthorp, a VITA student, and gilded by John Brass. Photograph: Richard Twinch.

First inset: Detail from the restored Minbar of Saladin in the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.

Second inset: Keith’s analysis of an Islamic pattern, showing how these are built from simple geometric relationships. From Islamic Patterns, p. 132.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] Lecture given for the Prince of Wales 70th birthday 2019: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6V1qwLOUKrI.

[2] Reflections: A film about time and relatedness (1977): see YouTube video

[3] KEITH CRITCHLOW: Order in Space (Thames and Hudson, 1969).

[4] KEITH CRITCHLOW: Islamic Patterns (Thames and Hudson, 1976).

[5] IAN SKELLY: ‘A Treasure Cave of Sacred Geometry’ in Resurgence Magazine, 2015, https://www.resurgence.org/magazine/article4334-a-treasure-cave-of-sacred-geometry.html.

[6] SHAHED SALEEM, Review in the RIBA Journal 2019.

[7] KEITH CRITCHLOW: The Hidden Geometry of Flowers (Floris Books, 2011).

[8] A tribute to Keith in BBC Radio 4’s Last Word, 26 April 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m000hhtj.

[9] LIZ GRAY: If you had breath for no more than 99 words, what would they be? (Darton, Longman and Todd, 2011).

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Video: The Art of the Ever-True. Duration: 32:29

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Harmony, Eternal Truths and the Krishnamurti Centre. Duration: 27:11

Video: Cambridge Mosque Geometer Keith Critchlow. Duration: 5:24

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Calligraphy – A Sacred Tradition

Distinguished calligrapher and geometer Ann Hechle talks about the underlying unity of the world

Mary, Seat of Wisdom and Mercy

Jane Carroll explains the symbolism of the Virgin at Chartres Cathedral.

A Thing of Beauty…

Emma Clark visits a Buddhist expression of human perfection, the Luohan, at the Temple Gallery in London

A Thing of Beauty…

David Apthorpe praises the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha, Sinan’s exquisite mosque in Istanbul

READERS’ COMMENTS

a beautiful life

1

Lovely to discover this and remember this lovely man. thanks Richard

Thank you Richard,

Wonderful to know more about him.