News & Views

The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth by Ben Rawlence

Jane Clark reviews a book about the effects of climate change on the great boreal forest at the top of the world

Tree line near the Arctic Circle, Finger Mountain region, Alaska. Photograph: Minden Pictures/Superstock

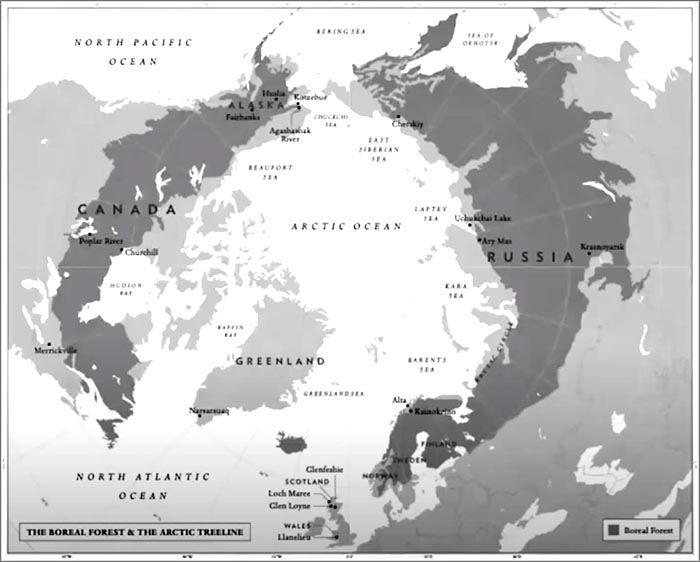

This is a fascinating and important book on many different levels. Its subject is the boreal forest – the vast band of trees adjacent to the Arctic Circle which forms a virtually continuous wooded area from Scotland to Greenland. The tree line is the northern-most point at which trees – as opposed to shrubs – can survive. And the central message is that due to global warming, it is moving north at an ever-increasing rate as the tundra melts and trees move into regions which have been beyond their range for tens of thousands of years.

Between 2018 and 2020, Ben Rawlence journeyed along this critical frontier, stopping off in Scotland, Norway, Russia, Alaska, Canada and Greenland along the way. Plunging intrepidly into some of the most inhospitable places in the world he introduces us to a variety of engaging characters: dedicated scientists who have been patiently monitoring environmental changes over decades; indigenous peoples who, having survived the ravages of colonialism and globalisation, are now facing a terminal threat to their way of life; and armies of volunteers engaged in reforesting new lands. Above all, he introduces us to the trees which make up the forest, upon whose remarkable properties and ability to adapt we all depend, but whose true nature and function, he informs us, we have barely begun to understand.

The extent of the boreal forest, showing the places Rawlence visited on his journey. Image: From the video Ben Rawlence on Treeline: 5 x 15 [/]

The Greening of the Tundra

.

First of all some facts. The rainforests of the Amazon have loomed large in discussions of global warming, but Rawlence tells us that the boreal forest is even more significant in terms of oxygen production. It occupies one fifth of the globe and contains a third of all the trees on earth, making it the second largest biome (or living system) on the planet after the oceans. Small changes therefore have huge implications for planetary processes everywhere.

For the past ten thousand years, the treeline has more or less tracked the ten degree isotherm – areas where the July temperature is ten degrees – but over the last three million years it has moved northwards and southwards numerous times as ice-ages have come and gone. Movement is therefore a natural process. What is alarming is the rate at which it is now happening. Instead of a few centimetres a century, we are seeing changes of 20, 50 or even 100 metres a year in some areas, leaving little time for ecosystems to adapt. And it is self-fuelling, as trees, once established, start to modify their immediate environment by warming the soil, thus increasing the rate of ice melt. (For more, see video below on the monitoring of the treeline by NASA.)

Video: Where the Trees Meet the Tundra: Decoding Signs of Climate Change. Duration: 5:51

One might ask: but what is the problem? Surely trees are a good thing, and a bigger forest means more oxygen and less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. In fact, reforestation is one of our frontline strategies against global warming. Rawlence explains that there are three main reasons why it is not such good news. One is that change at such a high rate creates instability, and hence enormous unpredictability across the whole global ecosystem; what we are seeing is unprecedented. Even the increase in the number of trees is patchy. Whereas the birch trees of Norway and the spruce of Alaska are proving able to adapt to the warmer conditions, in Siberia the larches in the north are dying because their roots become water-logged in the melting ice, and in the south they are being destroyed by fire as the climate dries. So there the forest is diminishing.

Secondly, the local effects upon the flora and fauna within the forest and the people who depend on them are potentially devastating. In Norway, for instance, Rawlence spends time with the Sami reindeer hunters and learns how the new areas of stubby birch are confusing the herds and disrupting their migration patterns. So the Sami, who rely upon their extraordinary ability to track the reindeer, are finding it increasingly hard, and dangerous, to find them. Similarly, in the Poplar River reservation in the great northern forest of Canada, his Anishinaabe guide Abel tells him that: ‘the moose are going, the birds are going, the rabbits are going, the caribou are nearly gone’ (p. 213).

Thirdly, and most important: huge quantities of methane and carbon dioxide are trapped into the ice of the tundra in the form of half-decomposed soil and vegetation deposited at the end of the last Ice Age. In Churchill, in northern Canada bordering on Hudson Bay, Rawlence encounters a great ‘tundra peatland’ where the carbon is stored: ‘1.1 trillion tonnes of it – more carbon than humans have released by burning fossil fuels so far’ (p. 234). Even more worrying is methane, which he sees for himself in a Siberian lake; ‘Deep down in the ice, small frozen bubbles are visible like pearls floating in the dark’ (p. 120). No one knows what the effect of releasing this will be, as methane is too hard to model and is not even included in current calculations. Consulting one of his scientists, Dr Ko van Huissteden, he discovers that:

… some studies have estimated that an unstable seabed could release a methane ‘burp’ of 500–5000 gigatonnes, equivalent to decades of greenhouse gas emission, contributing to an abrupt jump in temperature that humans will be powerless to arrest (p. 122).

The boreal forest, Western Sayan, Siberia, Photograph: Andrey_Ivanovr/iStock

The Wonder of Trees

.

However, The Treeline is not just a litany of doom. It is also a celebration of trees and forests, drawing upon the latest scientific research concerning their remarkable properties. In each of the six areas Rawlence visits there is a key species which dominates the forest; in Norway, it is the Downey Birch; in Russia the Dahurian Larch; in Alaska the white and black spruce. He describes how each of these species has unique abilities which enable it to survive in these harsh frozen lands.

This is impressive enough. But the forests also operate as integrated ecosystems and support a host of other living things – undergrowth, insects, animals and of course people – which have co-evolved with them. Thanks to the pioneering research by scientists like Suzanne Simard,[1] (see our review) we all now know about the complex underground networks of fungi which allow trees to communicate with each other – the so-called wood-wide web – but there is much more now being discovered.

For example, in Canada Rawlence meets the renowned biologist Diana Beresford-Kroeger [/] who has investigated the healing properties of the Balsam Poplar which is the key species in the boreal forest of Ontario. She describes how the local people use its sap and resin to cure a wide range of diseases, including diabetes, cancer and high blood pressure. She calls the tree ‘a treasure-trove of medicine’ and believes that as we learn more ‘timber may in fact be the least valuable use for the forest’. (p. 199)

She has also discovered that in spring the trees emit aerosols into the atmosphere which have a multitude of health benefits. They are antibacterial and anti-inflammatory for a start, but they also contain compounds which are essential for the development of the human brain and liver, and chemicals in the prostaglandin group which support the heart and cleanse the blood… and more. Rawlence immediately sees the global dimension of this, commenting: ‘This flush of tons of oleoresin into the atmosphere from millions of poplars of the boreal every spring acts like a health shield for all life on the planet ’ (p. 198, my italics).

Even more astonishing is Beresford-Kroeger’s discovery, based on the work of the Japanese scientist Katsuhiko Matsunaga, that the forests also have a crucial role in maintaining the health of the ocean. Matsunaga was struck by the collapse of the ocean food chain along the coast of his native Hokkaido following the clear-felling of the island’s trees. He went on to identify the cause as a lack of iron, which is a crucial element in the healthy development of phytoplankton. But they can only access it when it is bound and concentrated in larger ‘carrier’ molecules such as humic acid. This is made in the forests by decaying deciduous leaves from trees whose roots have ‘mined’ minerals such as iron from deep underground, and then washed into the sea by rivers. Despite its vital importance, scientists’ understanding of the humid acid molecule is apparently still far from complete (see p. 202).

Thus, it seems, trees are vital not only for the oxygen they themselves produce. They are also necessary for the flourishing of the algae of the ocean, which account for over 50 per cent of the photosynthesis in the world. Such recent discoveries indicate that they play a central role in the planetary ecosystem in multifarious ways which we are just beginning to suspect.

Balsam Poplar, with other trees, in Kootenay National Park in the Canadian Rockies, British Columbia, Canada. Photograph: Lee Rentz [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

An Optimistic Approach

.

It is these glimpses into the complex and delicate interconnections between all things on earth that makes this book so interesting and valuable. Rawlence’s capacity to see the larger picture also extends to his clear-sighted discernment of the connections between the environmental crisis and our present political and economic systems. In this respect, he is reminiscent of another writer who has plunged into the environmental debate, Amitav Ghosh, whose searing analysis of the connections between global warming, colonialism and capitalism is likewise combined with a deep awareness of the earth as a living and integrated whole.[2] (See our review.)

Rawlence’s previous books were about Africa; City of Thorns [3] was based on his four-year stay in the Dabaab refugee camp on the border between Kenya and Somalia, and tells the stories of nine long-term residents in what is probably the longest-standing camp in the world. He slowly came to realise that much of the driving force behind the massive population movement we are witnessing in Africa, though it is barely acknowledged, is climate change – in this case, drought and global warming – war and economic hardship being only secondary or exacerbating factors.

This insight generated the urge to investigate another region where, as he puts it in his excellent 15-minute summary of the The Treeline, ‘climate change is already history’. (See video at the end of this article.) Like Ghosh, he challenges our tendency to constantly displace the effects of global warming into the future. It is already with us, he tells us, and the world that we think we are living in no longer exists. Our only option now is to adapt.

And it is here that he shows himself to be an optimist, because he is confident that we – the human race – will be able to do this and find new ways of living in a radically different world. He is also confident that the trees of the boreal, which have already endured numerous ice ages, will survive. But he is less confident about many other species, and one of his big messages is that we have a real role to play in their fate. Talking about the need to prepare our children for what is to come, he comments in the last paragraphs of the book, that: ‘We and they are stewards, still charged with an ancient responsibility’ (p. 289). He likens us, therefore, to the prophet Noah, able to some extent to choose the creatures that enter the ark.

However, his optimism does not mean that he is politically naïve. In Kotzebue in Alaska he comes across the failed results of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANSCA) which was set up in 1975 in an attempt to reconcile the needs of the indigenous people with the installation of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline and comments that:

Alaska represents in microcosm the tragedy of modern industrial society. Despite the best efforts of the richest countries on earth to do the right thing on conservation and indigenous rights, the enduring commitment to the third demand – hydrocarbons – is undermining the viability of the rest. (p. 159)

Rawlence concludes that it is ‘… a bourgeois conceit that hope has become synonomous with saving – or attaining – an ideal state of affluent society, especially when affluence is incompatible with limits to economic growth’ (p. 285). Rather, for him, hope for the future lies in the adaptive versatility of human beings, and the fact that, as he observed in the African camps, crisis situations galvanise action.

In a disaster, the social order is stripped away and we are revealed to ourselves anew. The ‘human’ is unleashed, freed from its habitual constraints, sometime with barbaric consequences but more often with positive effects. People are capable of extraordinary things. What I learnt in the ruins of the refugee camps of Congo, Sudan, Uganda and Somalia is that struggle produces hope, not the other way round. Hope is not an inert precious metal lying around waiting to be discovered, it is something manufactured and redefined in the light of shifting circumstances, every day. (p. 285)

Accepting the situation we are in means, therefore, that ‘suddenly there is much to do’ (p. 286). To this end, he is now engaged in founding a new educational institution in Wales, Black Mountains College [/], which aims to give young people a grounding not only in the practical skills that they will need in a post-industrial future, but also to provide them with a theoretical grounding in the kind of integrated perspective which informs Treeline.

Sami Reindeer herders, Inari, Finland. Photograph: Rod Varley [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

Re-engagement

.

Rawlence’s over-arching message is that we need to re-engage with nature and adopt a model of change which he calls ‘co-evolution’ in which we acknowledge the mutual dependence and deep connection between ourselves and the other living beings on the planet. ‘A forest is not a static thing. It is a constantly evolving mosaic of species in multiple relationships with each other as well as with the rocks, the atmosphere and the climate. ’ (p. 281)

He gives us a word for this kind of highly interconnected system, coined by the Russian ecologist Vladamir Sukachev; ‘biogeocoenosis’.

Human beings have always been creatures of the forest, he tells us:

For 11,000 years since the last ice age humans have co-evolved with trees, moving into habitats pioneered by the advancing treeline and then adapting, managing and stewarding them, engineering a remarkably stable and convivial environment for nearly all that period on a global scale. (p. 282)

Re-engagement now means, on the one hand, putting ourselves in a position of learning – both about other natural beings and from them – and The Treeline gives us ample evidence that we have a very long way to go on this front. On the other hand, it means re-making our relationship and re-engaging at a personal level with nature as a living reality.

The ancient forest of Perucica in Bosnia and Herzogovina, one of the few remaining untouched forests of Europe. It is estimated to be 20,000 years old. Photograph: iStock

In Conclusion

.

The Treeline is not an easy book to read in many ways because it confronts us head-on with the reality of climate change and its inevitable consequences. But it also contains many pleasures, both in its deep understanding of what is happening to the natural world and in its joined-up thinking as regards political and economic realities. Rawlence writes well and keeps the narrative spinning along. What he is very good at is engaging with people and telling their stories, and along the way he manages to convey an enormous amount of factual information. And not only about trees: an important secondary theme is what we learn about the real lives of indigenous people in the 21st century

Where the book is bit more limited, from my point of view, is at the spiritual or metaphsyical level. Rawlence does touch upon about mythic dimensions which are so central to the world view of indigenous people – in Alaska, for instance, he talks about the native Koyukon vision of the world as ‘the land of the raven’ (pp. 176–7). He also expresses a firm belief in the responsibility of the ‘stewardship’ given to humanity, and a touching faith in our ability to adapt and change. But he does not articulate the basis for these views in terms of an overall vision.

Thus, although he talks about our need to re-engage with nature, he does not set out a coherent context within which this would take place. Is it just a matter of making time to sit with trees, or devoting our energy to working on the land? Valuable as these things are, I would argue that it will involve far more than this if we are to truly change our ways; we will need to rethink our whole approach to the natural world. And this necessarily involves integrating the spiritual dimension into our discussions of ecology, as it is only by looking from this perspective that ideas such as unity, interconnectedness and wholeness – or indeed, stewardship – really make sense. Therefore one misses in The Treeline any extended discussion of change at a deep metaphysical level such as writers like Colin Tudge, Iain McGilchrist and Karen Armstrong are arguing for.

But this is not to deny the value of the book. The great virtue of it is that it vastly extends our understanding of trees and enhances our appreciation of them. It also reminds us of our ancient relationship with the forests and how much we need them. ‘In the forest you are part of something magical and huge’, says Rawlence in his penultimate paragraph ‘where every step is simultaneously an act of destruction and creation, of life’ (p. 289) . It is good to remember this.

Video: Ben Rawlence on The Treeline; 5×15. Duration: 15:37

The Treeline was first published by Jonathan Cape in 2022, and has just appeared in paperback this winter (Vintage, 2023).

Jane Clark

is a writer, independent researcher and teacher who lives in Oxford. She is the editor of Beshara Magazine.

Sources (click to open)

[1] SUZANNE SIMARD, Finding the Mother Tree; Uncovering the Wisdom and Intelligence of the Forest (Allen Lane, 2021).

[2] AMITAV GHOSH, The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis by Amitav Ghosh (John Murray (London), 2021).

[3] BEN RAWLENCE, City of Thorns ((Random House, 2016).

More News & Views

Poems for These Times: 18 – New Year 2024

Benjamin Zepahniah | Faceless

“You have to look beyond the face

to see the person true

Down within my inner space

I am the same as you…”

Introducing… ‘Tiger Work’ by Ben Okri

Barbara Vellacott reads from and discusses a new book of stories, parables and poems about climate change

Book Review: “Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time” by Kapka Kassabova

Charlotte Maberly reviews a book about the search for wholeness, and a heartfelt plea to reclaim our spiritual, physical and emotional unity with nature

Book Review: “Work: A Deep History” by James Suzman

Richard Gault reviews a new book which takes a radical approach to contemporary work culture

Introducing… Bernardo Kastrup and Swami Sarvapriyananda

Charlotte Maberly appreciates a wide-ranging video conversation about Eastern and Western concepts of the self and mind

Connecting Threads on the River Tweed

Charlotte Maberly investigates an innovative project which explores cultural engagement as the driver of ecological change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

3 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

It is a great book with new insights into plant-human interaction, in particular how our moods and emotions are influenced by plant-symbiotic processes that science has revealed only in the last few decades.

What an amazing article we receive so many tremendous benefits from this wonderful plant species ,which the indigenous people of the world have always been aware of . These amazing facts about trees should be taught in schools so that there can be more respect and reverence for Mother Nature and earth as a whole .

Brilliant article ,Thankyou

Proper training is of utmost importance in the field of arboriculture, which involves the cultivation, management, and care of trees.