News & Views

The Sir Benjamin Baker window (1909) in the Nave of Westminster Abbey, featuring St George fighting the dragon. Image: © Dean and Chapter of Westminster

What makes one day different from another is commonly culturally dependent. For example, 5 November is resonant with people in the UK because it is Bonfire Night, commemorating the occasion when Guy Fawkes attempted to blow up Parliament in 1605, but it does not mean much to the French. But 14 July – the day of the storming of the Bastille in 1789, initiating the Revolution – does. The different religions award importance to days such as the start of Ramadan for Muslims, Yom Kippur for Jews and Diwali for Hindus; the Christian calendar has at least one saint associated with each day of the year. And, of course, each of us has our own calendar with its personal list of family birthdays and anniversaries. For me, for example, 6 May is important as it is my first born’s birthday.

So every day of the year will be special in some way to some people. Nevertheless, there are days whose significance straddles cultures, and 6 May is one of these. Indeed, it brings together cultures not normally seen as linked.

Khidr and St George

.

It does this because, firstly, although it may not be immediately obvious, 6 May is one of the days of the year which marks a stage in the annual solar cycle. The astronomical dates we are most familiar with are those of the equinoxes, when the length of day and night are exactly twelve hours, and the solstices, when the days are at their extremes. Festivals celebrating the shortest day of 21 December and the longest on 21 June are widespread. But oddly, in England, Midsummer Day (24 June) comes just days after the solstice which signals summer’s start rather than, as one would expect, around 6 August which is midway to the equinox. For the Celts, 24 June was mid-summer because their thirteen-week summer season began just over six weeks earlier on 6 May. They timed the start of seasons with the days which lay half way between an equinox and a solstice, and 6 May exactly divides the thirteen weeks between the spring equinox and the summer solstice.

The Celts named the festival on 6 May ‘Beltane’. It was the day to celebrate the beginning of the season when new life comes into full bloom. With the introduction of the twelve-month calendar by Julius Caesar in 45BCE, a more convenient date was adopted: 1 May, May Day. This, as Wikipedia [3] notes, is ‘around halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice.’

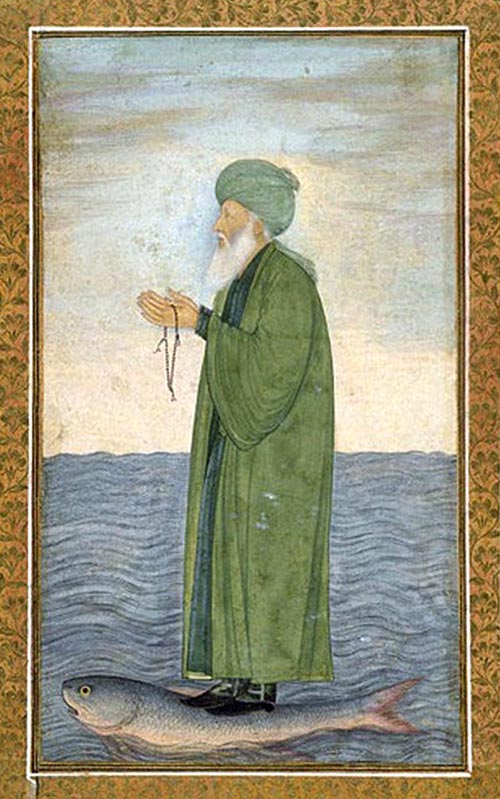

‘Around’ but not exactly. Far from the Celtic lands on the fringe of Europe, the precise halfway date continues to be celebrated. In the Near East, particularly in Turkey and Syria, 6 May is known as Khidr’s Day. Khidr [/] is a revered if mysterious figure within Islam. He is seen as an ever-living spiritual guide and importantly the bringer of life. As an immortal, spiritual being, Khidr is believed to have appeared in various guises over the ages, including that of Hermes for the Greeks and Elijah for the Jews. He is said to have been a teacher to Moses, Alexander the Great, and Ibn ʿArabi.

Khidr’s name translates as ‘The Green Man’. The Green Man has been a popular legendary figure across Europe for many centuries. A carved foliate head, a symbol of rebirth and resurrection, has been a widespread architectural feature of churches across Britain and the continent over the past millennia. The Green Man also featured as the Green Knight in the Arthurian tale of Sir Gawain. Some have even identified the famous medieval outlaw, Robin Hood, with him. The Green Man is a popular pub name in England. And he continues to inspire contemporary imagination. The Welsh equivalent of Glastonbury is the Green Man Festival held in Brecon each summer, for example.

But possibly the most important and intriguing equivalence is that between Khidr and the patron saint of England, St George, as King Charles himself has noted. Remarking what Christians and Muslims have in common, he has commented: “We forget too easily that the veneration of the Virgin is shared in the Middle East to this day by Christians and Muslims alike; that the mysterious prophet of the Muslims, Al-Khidir, was identified with… the Christian St George…”.[4]

This identity is well-attested, though the explanation for it is not immediately obvious: what do a life giver and a dragon slayer share? However, look a little deeper and common features do appear. Perhaps most essential is that both Khidr and St George are regarded as figures that protect the weak. St George clearly did. In his encounter with Moses as told in the Qur’ān,[5] Khidr three times gives aid, albeit in unexpected ways, to humble people. Hence in Turkey an ambulance was known as a hizir – the Turkish form of Khidr. St George also nurtures: in Bulgaria and Russia, he is the patron saint of farmers. Khidr even slays a dragon in a folk tale still told in Antioch in Turkey.

St George’s Day

.

But if St George is Khidr, why is his feast day 23 April? Shouldn’t it be 6 May too? Well, appearances can be deceiving. In fact, as I shall explain, Khidr and St George can be seen to be celebrated on the same day.

The current convention is to define days chronologically, and from this point of view, 23 April and 6 May are clearly separate dates. But days can be specified kairologically – that is, by the events that distinguish them. As I have already said, the Celtic festival of Beltane on 6 May marks the event of the sun reaching midway between an equinox and solstice. This is one way of identifying the half-way mark but there is another.

On 20 March the sun rises due east. In the days that immediately follow, sunrise occurs ever further north of east. The solstice, 21 June, is the turning point when the sun reaches its northern-most limit and then sinks south. Initially the rate at which the sun ‘moves’ north after the equinox is quite rapid, but its advance slows until in June there’s little further progress. Indeed, by 6 May the sun has already covered 70% of its journey north. When is the half-way mark reached? It is 23 April. So both St George’s Day and Khidr’s Day are, in their distinct ways, midway between the equinox and solstice and as such can be understood to be the same day.

And then consider, when is 23 April? This seems a nonsensical question that can only be answered tautologically. But actually, the answer depends on which calendar is being referenced. The calendar in general use around the world now is the Gregorian: the one instituted by Pope Gregory in 1582 (although only adopted in Britain in 1752). It replaced the calendar Julius Caesar initiated. However, the Julian calendar is still the one which the Orthodox Church goes by.

The Gregorian has been adopted because it is more accurate. For example, the spring equinox will always take place around 20 March using this calendar. The Julian measured the length of a solar year less accurately, and the effect of the inaccuracy continues to increase. Back in 1582, on the Julian calendar the equinox took place on 10 March. This year it will be 7 March, and 23 April Julian will be 6 May on the Gregorian calendar.

This explains why in Bulgaria, where St George is especially revered, the festival to honour him takes place on 6 May. The traditions surrounding the day in Bulgaria chime perfectly with the beneficence associated with life-giving Khidr: ‘[The day] is connected with a lot of rituals for obtaining health and fruitfulness for the people, animals and fields.’ [6] People bathe in the morning dew (also a traditional May Day activity) and doors are decorated with fresh green plants (as on Beltane in rural Ireland).

Hence in Bulgaria and much of Eastern Europe it may seem quite obvious why an English king should choose 6 May to be crowned. After all, St George is the patron saint of England, is he not? Likewise in Turkey and the Levant: while people celebrate Khidr’s Day, they may recognise the connection with St George and all that he represents.

6 May, then, is a truly remarkable day and an auspicious one. While offering lessons on the nature of time measurement (amongst others, why Midsummer Day is so close to 21 June), it more importantly shows us that the peoples of the lands stretching from the Atlantic to the Euphrates share more than is commonly understood. Though their myths take different forms, their origin may reflect universal meanings. So through the choice of this date, we are being given the opportunity to seek out the truths that unite peoples ostensibly very different from one another.

Sources (click to open)

Dr Richard Gault is a regular contributor to Beshara Magazine. He has worked at universities in Scotland, Ireland, Germany and The Netherlands, where he has taught and researched a variety of subjects, including the history and philosophy of science and technology. He is a long term student of the Beshara School and from 2015–2017 was principal of The Chisholme Institute in Scotland.

More News & Views

Poems for These Times: 18 – New Year 2024

Benjamin Zepahniah | Faceless

“You have to look beyond the face

to see the person true

Down within my inner space

I am the same as you…”

Introducing… ‘Tiger Work’ by Ben Okri

Barbara Vellacott reads from and discusses a new book of stories, parables and poems about climate change

Book Review: “Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time” by Kapka Kassabova

Charlotte Maberly reviews a book about the search for wholeness, and a heartfelt plea to reclaim our spiritual, physical and emotional unity with nature

Book Review: “Work: A Deep History” by James Suzman

Richard Gault reviews a new book which takes a radical approach to contemporary work culture

Introducing… Bernardo Kastrup and Swami Sarvapriyananda

Charlotte Maberly appreciates a wide-ranging video conversation about Eastern and Western concepts of the self and mind

Connecting Threads on the River Tweed

Charlotte Maberly investigates an innovative project which explores cultural engagement as the driver of ecological change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Many thanks indeed for this truly fascinating article which opens up so many avenues for further exploration. Onwards! GE

I note the Green Man on the Coronation invitation. The King knows more than he lets on?