News & Views

A Secret History of Christianity

Jesus, the Last Inkling and the Evolution of Consciousness: Johnathan Sunley reviews a new book by Mark Vernon

Image of Christ in the Hagia Sophia, Istanbul (587CE). Photograph: Alessandro Calzolaro/Adobe Stock

It might be assumed from a glance at the title of this book that its author is going to let us into a long-suppressed secret about Christianity – something to do with the Knights Templar, perhaps, or the occult – that will shatter our perceptions of the religion. Vernon is not interested in secrets like these. But he is very interested in the way that a deep engagement not just with Christianity but with the truths preserved in other religions and wisdom traditions can shatter everything we think we know about the world.

As a former Anglican priest with a PhD in ancient Greek philosophy and degrees in physics and theology, he is well placed to try and deal with these issues. But Vernon is also a psychotherapist and it is perhaps this perspective that makes the approach he takes to Christianity so enthralling. He notes how the combined forces of scepticism, secularism and consumerism are making the religion unthinkable for all but the most fervent believer, even if some of its festivals – such as Christmas –do linger on in the calendar. But the problem lies less with its atheist enemies, he tells us; Christianity’s real troubles are to be found in its inner life, which for the last several hundred years has been slowly dying.

This is not a long book but in it Vernon covers a huge amount of ground – it is worth reading just for the mini-histories of Old Testament Israel and the Reformation – and he does so assisted by an exceptional guide: Owen Barfield. A close friend of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien, Barfield is sometimes known as the ‘last Inkling’ because he outlived all the other members of that gifted group (he died in 1997). But what he should be known for are two of the twentieth century’s most original and important studies in language and philosophy: Poetic Diction [1] and Saving the Appearances [2].

In these works, Barfield looks at the way words change meaning over time and comes to the conclusion that what is really changing is consciousness itself – that is, how humans experience themselves and the world around them. This happens, he proposes, in three phases. To begin with there is little differentiation between processes that we call ‘inner’ and ‘outer’. In ancient times people lived with gods, spirits, nature and even the dead as though these were all part of themselves. Barfield names this phase ‘original participation’.

This is then followed by a ‘withdrawal of participation’ as men and women start to think of themselves as individuals. This is a period usually associated with literacy and the birth of philosophy and science. But it can also feel like a time of loss and disorientation, as people realise that they are separate from both each other and the universe as a whole. Finally, though, there is the possibility of ‘reciprocal participation’, an era of highly evolved consciousness in which the defining features of the other two phases are brought together. As Vernon puts it: “Now, the inner life of the individual is felt to belong to him – or herself – the gain of the withdrawal – but also to reflect the inner life of nature, the cosmos and of God.” (p.4)

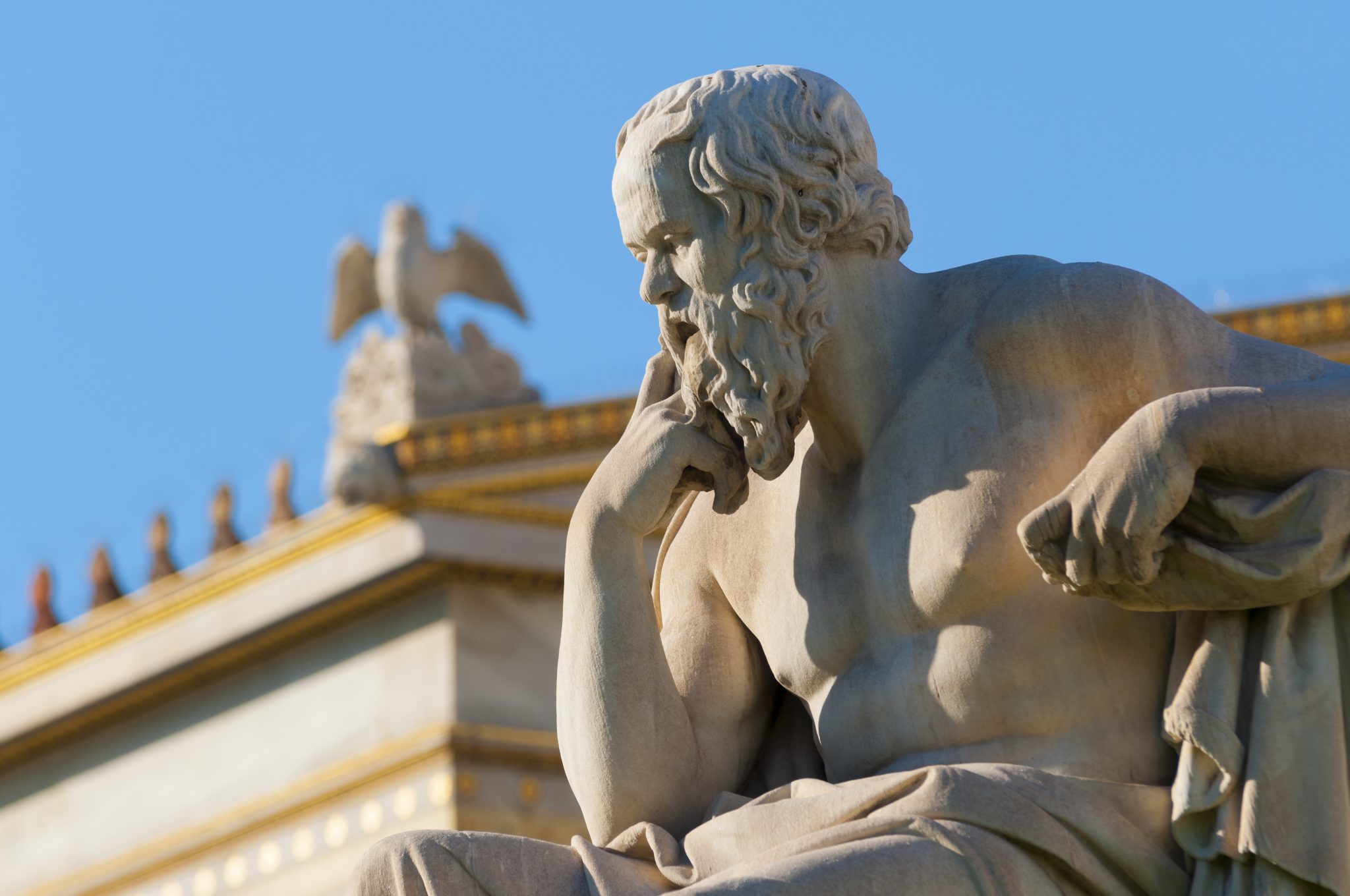

Socrates as depiced by the 19th-century sculptor Picarelli in front of the National Academy in Athens. Barfield saw Socrates as bringing a new consciousness of the inner life. Photograph: Alraelf/Adobe Stock

The Evolution of Awareness

So where are we today in terms of this schema? We are brilliant at science and technology. We also have a strongly developed sense of our own subjectivity. There is nothing wrong with these capacities in themselves and it would be absurd to ask us to forego them. But these gains in consciousness have come at a cost. For we now find ourselves oppressed by a feeling not just that God is dead but that the universe is too – notwithstanding the unlikely accident of our own planet.

Whereas most other models of history are linear, Barfied’s is cyclical. Vernon draws our attention to this and to the hope he thinks it offers us. The loss of connection with nature and the divine that the West has suffered since the onset of the modern period can certainly be considered traumatic. But this is not the first time we have been through a withdrawal of participation on this scale. Something similar happened in the centuries leading up to the birth of Jesus. Yet what followed was the awakening of a sense of reconnection and of a new kind of wholeness: an era of reciprocalparticipation that lasted for the best part of 1,500 years.

Vernon presents a fascinating account of the shifts in spirituality and overall awareness that unfolded among Jews and Greeks during the first millennium BCE. Thanks in no small measure to the genius of their prophets and philosophers, both peoples gradually came to feel the richness of their inner lives. More and more they experienced the divine in their hearts, rather than in sacred places, revered texts or temples. He explains:

The unfolding did not stop there. The prophets and sages began to feel that the full implications of these subtle shifts had to be incarnated. To be wholly realized, the inside of the cosmos needed to be manifested not just in the ideas of perceptive teachers but in the life of an individual. (p.8)

With Alexander the Great’s invasion of Jerusalem in 331 BCE, suddenly the stories of these two peoples converged and an irresistible momentum began to build that culminated in the incarnation. It is an event that changes everything. “The life, death and resurrection of Jesus marks a point of no return.” (p.134) This is not because ‘Jesus saves’, as modern-day evangelists sometimes like to say. It is because, Vernon believes, “Jesus initiates a way that can become our own”. In one sense the relationship he had with God was unique. No one else could claim to be God’s son. But what Jesus meant by this, says Vernon, was that he knew God in the way that sons and fathers know each other, in a bond of intimacy and mutuality. A son participates in the life of the father – and Jesus’ message is that it is open to us all to participate in God: we just have to surrender ourselves both to knowing him and to being known by him.

Right through until the end of the Middle Ages, Christianity both tended and taught what might be seen as a sort of open secret. Jesus had been both fully God and fully man and in doing so had transformed what it means to be human. But then with the Reformation and the rise of science, there was a new and in some respects much-needed emphasis on the individual again. Barfield observes that this is when modern-sounding words hyphenated with ‘self’ such as ‘self-confidence’ and ‘self-pity’ enter the language. Christianity survived and survives to this day. But the mystery of the incarnation no longer had the power to illuminate everything in the universe and soon not even the Church could remember how it had once been possible for an individual to feel that his or her interiority was connected with the interiority of God.

Owen Barfield. Photograph: theimaginativeconservative. org

We Must be Mystics

Where does this leave us now? Vernon thinks that there is no going back to the glory days of Christianity but that we can achieve a form of reciprocal participation right for our times. To do so, we need to accept our individuality rather than condemn it. But we need also to appreciate how our minds can serve as a doorway to the divine. The door opens when we realise the potential of our imaginations. As Vernon puts it: “The secret life of things, their presence and soul, will only be steadily regained imaginatively.” (p.165)

The last chapter of A Secret History of Christianity is titled ‘We must be mystics’, acknowledging a quotation from the theologian Karl Rahner that is one of the book’s epigraphs: “The Christian of the future will be a mystic or he will not exist at all.” Vernon draws on Shakespeare, Traherne, Blake, Coleridge, Einstein and the psychotherapist Donald Winnicott to show that this future is already here. What these figures have in common is the awe they feel towards the imagination as an intermediate zone that lies between the subjective and the objective. For them it is what Vernon calls a ‘region of revelation’. And so it can be for us when we take genuine inspiration from it.

In his early life Barfield had a transformative experience of this kind when he recovered from a period of severe depression through reading poetry. He would later write extensively about the imagination, metaphor and poetry, and the relationship of all three to consciousness, having understood that what he experienced was, in Vernon’s words, “not only contained in the power of poetic words, but throughout the cosmos and nature”. (p.174)

Finishing this last section of the book, I was reminded of the lines that close a now little-known work from the 1960s by the American polymathic philosopher Norman O. Brown. Readers of Beshara Magazine might be aware of Brown from his writing about Islam – and about Henry Corbin in particular. His book Love’s Body [3] is a remarkable achievement in scholarship that also comes across like a radical manifesto for the imagination. It ends with this statement: “The antinomy between mind and body, word and deed, speech and silence, overcome. Everything is only a metaphor; there is only poetry.”

A Secret History of Christianity: Jesus, the Last Inkling and the Evolution of Consciousness by Mark Vernon was published by Christian Alternative Books [/] in 2019.

Johnathan Sunley is a psychotherapist and writer who lives in London.

More News & Views

Poems for These Times: 18 – New Year 2024

Benjamin Zepahniah | Faceless

“You have to look beyond the face

to see the person true

Down within my inner space

I am the same as you…”

Introducing… ‘Tiger Work’ by Ben Okri

Barbara Vellacott reads from and discusses a new book of stories, parables and poems about climate change

Book Review: “Elixir: In the Valley at the End of Time” by Kapka Kassabova

Charlotte Maberly reviews a book about the search for wholeness, and a heartfelt plea to reclaim our spiritual, physical and emotional unity with nature

Book Review: “Work: A Deep History” by James Suzman

Richard Gault reviews a new book which takes a radical approach to contemporary work culture

Introducing… Bernardo Kastrup and Swami Sarvapriyananda

Charlotte Maberly appreciates a wide-ranging video conversation about Eastern and Western concepts of the self and mind

Connecting Threads on the River Tweed

Charlotte Maberly investigates an innovative project which explores cultural engagement as the driver of ecological change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Sources (click to open)

[1] OWEN BARFIELD: Poetic Diction (1928: Barfield Press UK, 2006)

[2] OWEN BARFIELD: Saving the Appearances (1957: Wesleyan University Press, 1988)

[3] NORMAN O. BROWN: Love’s Body (1966: University of California Press, 1990)

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

2 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Thank you. Bessarabia Magazine is a wonderful source of contact, ideas and inspiration through its wide ranging articles.

It all points on the right direction, even if we none of us know quite what that direction ( or direction-less-ness ) is yet.

On behalf of the Beshara Trust I thank you for your remarks about the Magazine. We now have 56 articles published and look forward to the next 56! Regards, Gill Williams, Chair, The Beshara Trust.