Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 25, 2023

Bringing Light to the World:

the Vision of Ibn ‘Arabi

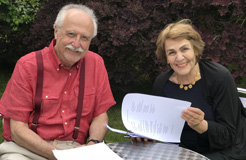

Dr Eric Winkel talks with Jane Clark and Richard Gault about what the wisdom of the great 13th-century philosopher/mystic can offer us in these troubled times

Bringing Light to the World: the Vision of Ibn ‘Arabi

Dr Eric Winkel talks to Jane Clark and Richard Gault about what the wisdom of the great Islamic philosopher/mystic can offer us in these troubled time

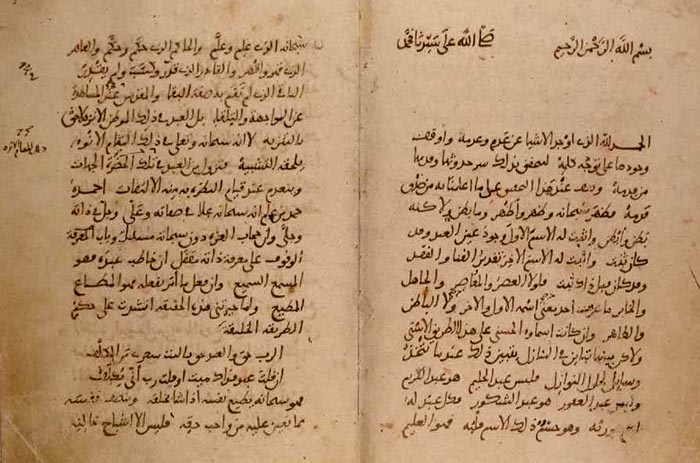

Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi [/] (1165–1240) is one of the most important masters of wisdom within the Islamic spiritual tradition. Designated ‘the greatest teacher’, his vision is based on the principle of unity – the unity of being – and in his many books and writings he explores the implications of this unitive perspective at every level of being, from the spiritual to the material. He has been less well-known in the Western world than other Sufi thinkers such as his contemporary Jalal al-din Rumi, but in recent decades there has been a revival of interest in his ideas, and a flourishing of publishing and new translation. Dr Eric Winkel is involved in one of the most ambitious of these projects, bringing into English Ibn ʿArabi’s massive master work The Openings Revealed at Makkah (al-Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya), [1] which consists of more than 9,000 pages in the original Arabic text. He spoke with Jane Clark and Richard Gault by Zoom during a recent visit to the UK about the continuing relevance of his vision for the contemporary world.

Jane: In the face of the present global situation, with war raging in Palestine and the Ukraine, as well as in many other places, and all the human suffering and religious division that we’re seeing in the world – not to mention the ever-present problem of climate change – what is it that Ibn Arabi’s unitive perspective can offer to humanity? What is its value?

Jane: In the face of the present global situation, with war raging in Palestine and the Ukraine, as well as in many other places, and all the human suffering and religious division that we’re seeing in the world – not to mention the ever-present problem of climate change – what is it that Ibn Arabi’s unitive perspective can offer to humanity? What is its value?

Eric: Well perhaps the first thing to say is that Ibn ‘Arabi himself hated violence in all forms; he was a very, very gentle person. I felt that from the beginning, as soon as I began to read him. Like us, he lived at a time of great upheaval and political change; he was in the heartlands of the Islamic world at the time of the fourth Crusade, when the empire was under attack on several fronts, and Jerusalem changed hands three times during his lifetime. In various places, he talks about what he saw, and in particular the way that the commander of the Muslim forces, Salah al-din Yusuf bin Ayyub (Saladin [/]), behaved during the war. Within traditional Islamic culture, there were rules about the way that war was conducted.

But today we are in a qualitatively different situation in which these traditional rules don’t apply. My first area of study, in which I got my PhD, was in political philosophy, so I am very familiar with what people in that sphere would say about our current crises. But what I have come to by studying Ibn ‘Arabi is that it is not helpful to look at societies or politics, or analyse the behaviour of groups of people and things like that, because in the end, everything is an individual spiritual problem or issue. If you consider, say, racism and ask: Where does it come from? How does it perpetuate and become normalised? Or you look at military violence and territorial domination, and ask: How is it initiated and maintained? How is it strengthened? – then the answer is that all these things come down to the actions of individuals.

When people are alienated, they’re able to do things that they wouldn’t do otherwise. Do you remember that in the 60s and the 70s, there was a famous study in psychology called the Milgram Experiment [/], where the scientists would put on a white coat and ask subjects to push a button which would appear to hurt someone in another room. They wanted to find out how far people would go, and the conclusion was that some people would go very, very far. So all these things – violence, racism, oppression – happen within ourselves.

Seeing from the Heart

.

Jane: So your view is that the most important thing in our present situation – well, in any situation – is to take note of our own state and motivations?

Eric: Ibn ʿArabi tells us that everything that happens comes from the interior, which means it comes from who we are and what our intentions are. He talks a lot in the The Openings Revealed in Makkah about the importance of intention, and the spiritual masters who understand its significance. These people always look at the interior state first, and understand what appears on the outside as coming out of that. Whereas most of us are educated to see things the other way round; we look primarily at the outside and then consider how that affects the interior.

One of the characteristics of these masters of intention is that they are concerned with cultivating personal accountability. They train themselves to account for every deed that they do, every speech that they give, even every thought they have. It is said that some of the great Sufi masters, and Ibn ‘Arabi tells us in his autobiography that he was one of them, would actually write a journal every night in which they noted down everything they did during the day. But if there are things that are distracting us throughout the day and throughout the night, then we’re not going to be doing this kind of personal accounting. Or if we’re dominated by fear. So if people are distracted and living in fear, then no one is going to be able say, this is wrong. Distraction and fear is how people get controlled.

Richard: What you’re saying implies there is such a thing as right and wrong, or truth, and other qualities such as beauty. This is very much in line with ancient philosophers, such as Plato and Pythagoras, who saw such things as givens, whereas these days it is more commonly understood that these values are just subjective, or relative. We believe we can choose our own truths, our own idea of what beauty is. But the case for the traditional point of view is still being argued by some people – for instance, by philosopher Iain McGilchrist in his book The Matter with Things,[2] which I reviewed last year for the magazine (click here). McGilchrist urges us to recognise that there is a reality – an objective reality – to these ancient core values of truth, beauty, justice; he calls them ‘ontological primitives’, meaning that they cannot be reduced to anything else (see also our interview with McGilchrist).

Eric: Yes, at some point we have to get out of the head and out of the intellect and ask: Can we look with our hearts? Because when we look with our hearts, we know what beauty is, and we know what justice is, and we know what truth is.

Jane: When you talk about the ‘heart’ you are not just talking poetically, but referring to the idea within the Sufi tradition that we have a specific organ of perception by which we can perceive mystical truth – or Ibn ʿArabi would say, by which we perceive the true nature of things.

Eric: Indeed. And the greatest danger we face today is not being able to tell truth from falsehood. I’m sure many intellectuals today will say that that sounds very binary and therefore very old fashioned, but just about every chapter of The Openings Revealed at Makkah ends with the words ‘God speaks the truth and is the guide to the way’. I was living in the USA during the Trump era, and what Trump learned was that if you repeat a lie often enough, eventually it sounds true. And if you just keep lying and lying and lying, when you say something true, it really doesn’t matter. So we can come to point where even things that are true look false.

Within Islam, there is a hadith – a traditional saying of the Prophet Muhammed – that if possible we should change things with our hand. If we can’t change them with our hand, we should change them with our mouth – so we speak out against them. And if we can’t do that, then we should change them in the heart. And this last is actually the most important and the most difficult one, because it’s easy to fight and it’s easy to speak. But it’s not that easy to know the true from the false in the heart. So Ibn Arabi is very clear that we should always work from the heart. And this brings us back to the matter of intention; seeing the interior first and then looking at the exterior.

Jacob’s Ladder by William Blake (c 1799–1807) which vividly depicts the vertical dimension of the spirit. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

Move your computer mouse over the image in order to enlarge

The Two Worlds

.

Richard: One of the problems we have in understanding what it might mean to look first of all at the interior, is that we no longer believe that there is an interior, particularly when it comes to the material world. We live in a culture which has developed an ontology which is completely flat, horizontal, so anything that happens can only be explained in terms of cause and effect within the world itself. Whereas traditional wisdom, of which Ibn ‘Arabi was perhaps the most explicit exponent, believed that there’s another deeper reality – or we might call it a vertical dimension – to what appears in the world. So what we see here is just the effect of realities or events which are happening in this other world – this interior or vertical dimension – and it is there that we find these absolute values which are perceived by the heart.

Eric: Yes, Ibn ‘Arabi of course would completely agree with this, and he is always looking at these two worlds together. There is no solution to any of our problems if we only look at one of them. If we start to understand that this other dimension is really there, then we also begin to see that that what we call ‘the external world’ is actually an arena. An arena is a sandy area where you fight or compete, or where a display is put on. So it is a place for the acting out of events and happenings which are coming from this other dimension. And in the Islamic tradition this is spoken about as the interplay of ‘the divine names’. The divine names are coming into the arena, they’re separating, they’re mixing, they’re unmixing; some of them are opposites and so they clash; some of them are harmonious with each other – all of them coming from a single reality.

Richard: Could you explain more about these names? Could we perhaps think of them as qualities or attributes? I know there is a tradition of reciting or invoking what are categorised as ‘the 99 most beautiful names’, which include some which are encompassing such as Mercy and Life, but some which are in opposition, like the Forgiver and the Avenger.

Eric: The divine names are what we might call the ‘grammar’ of the cosmos. They are nouns which denote things – the entities that we see. They are also qualities, which makes them adjectives, and they are actions, verbs. They are not limited to the 99 that are mentioned in the Qurʾan and which, as you say, are used in invocation and praise. Everything that happens comes about through a divine name. So you could use the word ‘force’ maybe; there’s a divine force there.

Jane: So thinking about these two worlds: if what we see is really a projection of something that is taking place behind the scenes, as it were, by trying to understand what is going on by looking in only one place – the arena – without also looking at the place where the names originate, we will never succeed because we don’t have the whole picture.

Eric: Yes. But the important thing to remember here is that the display is not for us. The world is not made for me. If it was, it would be different, believe me. There would be fewer jerks and less violence, and a whole lot less of all sorts of other things. Ibn ‘Arabi tells a story about this. He describes how one day he met one of the Substitutes – a class of people who in the Islamic mystical tradition are regarded as having a spiritual function in the world – and started complaining to him about the ruler of his region, whom he called a tyrant: ‘this tyrant who is so oppressive’. And the person said to him: ‘Stop! Who are you to get in the way of the master of creation and the creation?’ Meaning, who are we to get in the middle of this process of manifestation we have just described and say that creation ought to be this way or that. I have been very interested to note that in Ibn Arabi’s writings there is no ‘ought’ and ‘should’; the words never come up. There is just the way things are.

Ibn ʿArabi gives us some encouragement in telling us this story, because it shows that even the greatest spiritual masters can forget that the world is not made for us, but rather it is the arena for the divine purpose.

Jane: So what are the implication of remembering this for our own approach to injustice and suffering?

Eric: Well, the story goes on, for then the man says to him: If the ruler – the king, the powers that be whoever they are – are good, then this is good for them and good for you. But if the ruler is oppressive, then it is bad for them but still good for you.

In saying this, he is taking into account both worlds. In the first case, it is good for the ruler because they’re going to be blessed in the next world; they’ll be rewarded for being good sovereigns. And it is good for us because we can have a nice life; we can run our businesses and bring up our families in peace, without people coming to kill us and so on.

In the second case, if the ruler is oppressive, then it is bad for them as they’re going to be punished in the next world, and it is good for us because we are taking on suffering that is undeserved. We are taking on difficulties that are not of our making, and this is purifying for us. And we need to be purified, because we are human beings and so inevitably we have done harm: we’ve stepped on ants and we’ve hurt bees and animals, and as we grow up we have almost certainly been mean to some people. We ask for forgiveness in our prayers not because of things we have done in the minutes or hours immediately before the prayer, but because of all the things we have done because of our human nature.

And this understanding is an advantage of being a person of faith: we can see that when something bad happens to us that is undeserved – not only the action of tyrants and oppressors but things like illness as well – it is cleansing and good for us. And this relates to something the caliph Umar said when he was asked: Why do we praise God? Why do you say all praise belongs to Him for everything that happens, good and bad? And he said: You should never be thankful for bad things; you should be thankful for what you get from the bad things.

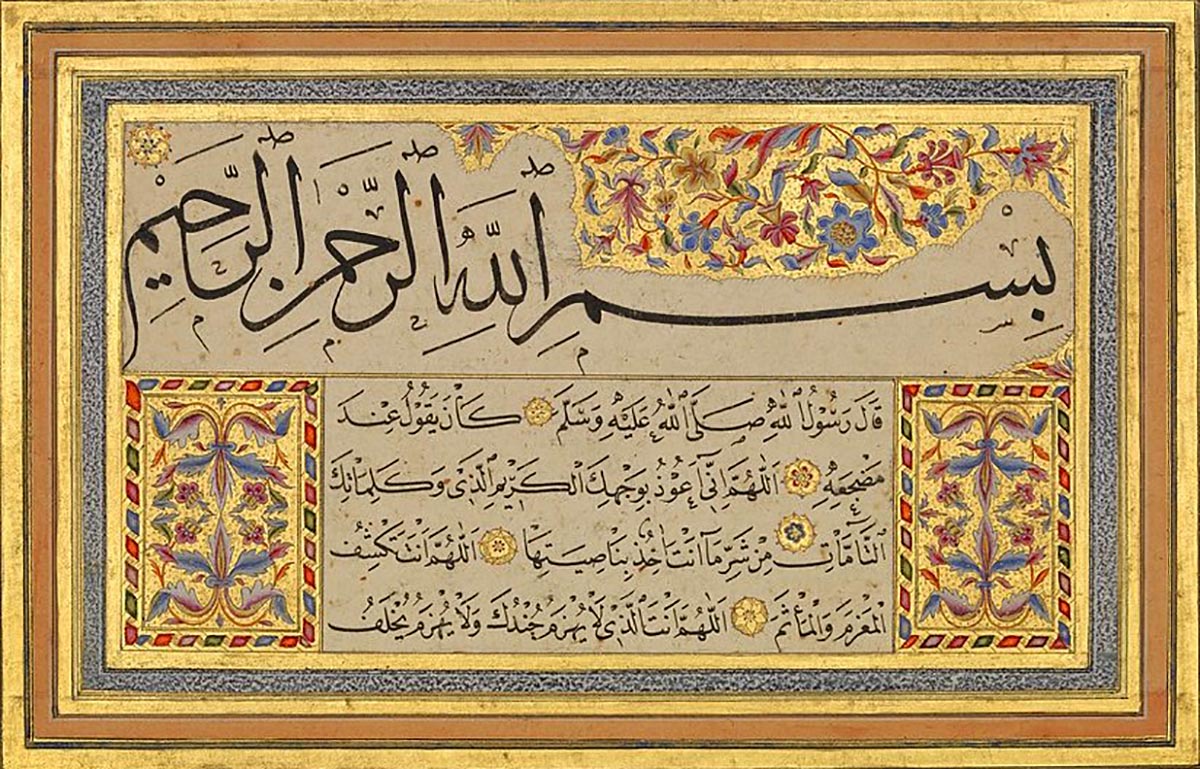

A late Ottoman calligraphy by Hafiz Osman, showing the heading ‘In the name of God the merciful and the compassionate’ which starts every chapter of the Qur’an. From an album compiled in Istanbul, c. 1730-1754, now in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (T 447, f.1v). Image: via Wikimedia Commons.

Move your computer mouse over the image in order to enlarge

The Necessity for Compassion

.

Jane: I accept that what you are saying is deeply true, but at the same time, I feel that it does not mean that we should just passively accept everything that happens. Many people, including myself and I believe you also, are quite committed to making the world a better place not only for ourselves but for everyone else. And this is because of another aspect of Ibn ‘Arabi’s thought, which is his emphasis upon the compassion of God. He was explicitly committed to bringing out the meaning of well-known traditions within the Islamic faith such as ‘My compassion encompasses everything’ [3] and ‘My compassion overrides My anger’ [4] which tell us that mercy is the ultimate end of everything. Compassion demands that we care what happens to other people and other beings, does it not?

Eric: I have been asking about this issue for many years now, and what comes up for me is an event that is recounted about the Prophet Muhammad. A child, a newborn child, was very weak and shaky and clearly going to die quickly. So word was sent to the Prophet asking him to come and visit. But he was far away, so he sent a message instead, saying all the things that we have just said about the divine names and not interfering with the creation, and also reassuring the mother that there would be recompense for whatever was taken away from her, and that a child who dies like this will be in paradise, etc. But she sent word back; tell him he must come. And it went backwards and forward several times like this until eventually he gave in and went to visit her.

Then, when he was there, he just held the child and began to cry, and cry and cry, and didn’t say a word. Later people asked him: What are those tears? And he said: Those tears are the supreme compassion, al-Rahmān. This is what compassion is. We can say all we want about the divine names and such like, but face to face, in presence, there’s nothing but tears.

Jane: So you would say that once again, this comes down to the individual and an individual interaction. And being present in the moment.

Eric: Yes. When I look at my own life and experience, if something horrible is happening to me, the one thing I want is that people know about it and recognise it. If they’re just walking around and are completely oblivious to it, that makes the hurt greater. I taught my kids this when we were living in places like Pakistan and India, where as you’re walking on the street you meet people in extreme need. Some of them are professional beggars, of course, but many of them are simply just in horrible shape.

I said to my kids: We are not necessarily going to give money to everyone, because frankly we can’t. We can’t take home and feed every single person in the world. But we can look at them and give them a peace greeting – let them touch our heart. They argued with me, saying: But the moment you do that, you’ve engaged with the beggar and they won’t leave you alone. I said: Well, that’s neither here nor there. The important thing is that you’ve recognised the human being in them. Because the one thing that person needs – the first and most important thing they require – is attention. The money that I can give is limited, but my attention can go anywhere.

Shadow puppet theatre (Nang Yai), Thailand, Southeast Asia, Asia. Image: robertharding / Alamy Stock Photo

The Human Being

.

Jane: And this leads on to another important aspect of Ibn ‘Arabi’s thought, which is what he says about the value of the human being. He maintains that you cannot exaggerate this, and argues strongly that the preservation of human life should have precedence over the propagation of beliefs or dogmas, because of the place of the human being in the universe. He also points out that if you kill someone, even if they’re a bad person, you’re also killing all their potential progeny down the ages. You’ve no idea who they might have become, and so you are answerable for that as well.

Richard: I have been thinking that this is one of the paradoxes of modern life. On the one hand, you could say that people’s egos are too strong and they are too self-absorbed. But on the other, we don’t really appreciate just how extraordinary the human being is. Many people seem to believe that the difference between a monkey and a human isn’t that great; life is just a continuum, and we happen to be at the top of it. But in Ibn ʿArabi’s view, the human being is qualitatively different from all other forms of life or existence, and that gives us a glory that we need to recognise. If we did acknowledge it, then we would indeed show more compassion to others whom we recognise also as being miracles.

Eric: Actually, Ibn ‘Arabi makes a very clear distinction between what he calls humans and human beings. Humans in the ontological hierarchy are a continuation – a further step up – from minerals, plant and animals. But there is a further step beyond that, which is what he calls ‘the human being’, who is described or characterised by being the place through which the divine names manifest. Again, this points to the importance of the individual, because if a person becomes a place of manifestation of a divine name, there’s no limit to what that name can do. Clearly, as mere humans we are limited in the effect we can have – limited physically, emotionally, psychologically and spiritually – but if we become the vessel for a divine name – if we are able to become like an empty space, a blank slate, in which divine action can manifest – then anything can happen.

The best way I can explain this is to bring in another metaphor which Ibn ‘Arabi often uses to describe what is going on in creation – the shadow play. If we think of the schematics of a shadow play, it involves there being two places. On one side there is the divine reality, which is Allah or God in Himself, the Real, however we refer to it, who has qualities such as being All-seeing, All-knowing, All-compassionate, which are quite unlike us, and on the other we have the screen on which the image is cast, which is the creation. And in the middle we have the divine names, or the human being who is the place of manifestation of the divine names. This middle place looks both ways; with one face it looks towards the divine, and with the other it looks towards the creation.

If someone is in this middle place, then they see with the divine sight; they see with their eyes, but they also see with the divine light, which has been entwined in their sight. The Qurʾan talks about people who see but yet don’t see, meaning that they see but they don’t understand. Or they hear but they don’t listen. What is meant is that the senses are giving them the data, because they receive the sound waves, etc., but there’s no light wrapped up around it, so there’s no meaning or understanding given. The data is simply data. But when light is wrapped around it, we get data plus light, which gives us understanding – listening instead of just hearing.

So going back to the original question about the situation we find ourselves in; we’re not going to solve the problems of the shadows by talking to shadows. Trying to make better shadows, bigger shadows, smaller shadows, prettier shadows, more gentle shadows – none of that will work. What we want to find out is: how can we get more light into the world?

Richard: So how do we?

Eric: Well, Ibn ‘Arabi tells us that there are two ways that the light gets put onto the senses. In the shadow play metaphor, the place in the middle is like a filter or a membrane. The light hits it and casts a shadow onto the screen of the world. You cannot have light on that side, you can only have shadows. But we can reintegrate the light into the senses. And that reintegration is called taḥqīq in Arabic, which means to make something true. ‘To make something true’ is to shed divine light on it.

For instance, we talk about the light of faith, because when I see someone giving money to someone in order to help them, I can either say: Oh, what a stupid person, he’s losing his money, or I can say: What a wonderful gesture – they are so generous. So the act has no meaning in itself. The meaning is put on it by faith, so that you see, for example, that the widow’s mite is worth more than the millionaire’s donation.

Richard: You are referring here to the story in the New Testament when Jesus saw a group of rich people putting gifts into the treasury, and a poor widow putting in just two small coins. He said ‘Truly this poor widow has put in more than all; for all these out of their abundance have put in offerings for God, but she out of her poverty put in all the livelihood that she had.’ [5]

Eric. Yes. If you see with sight entwined with light, then you see the mite’s true value. If you don’t, then it’s just a little coin, and compared to the million dollars the rich man may have given, that’s nothing. So this is an example of putting the light back into the world.

The other way light gets put back on is embodied in the term kashf, which means disclosure. So that’s when everything gets revealed, and you see the light that is entwined in the senses as it was before it hit the membrane.

So if we were to ask: How can I make my life meaningful? Or: How do we make the world a better place?, then the answer is that we need to put light back into all of the senses. There is a beautiful poem by the Mexican activist and healer Grace Alkvarez Sesma that we read recently in a group study:

Bless my eyes that I may see with love

Bless my lips that I may speak with love

Bless my ears that I may listen with love

Bless my heart that I may give and receive love

Bless my hands that all I touch feels love

Bless my feet that my walk be a prayer upon Mother Earth

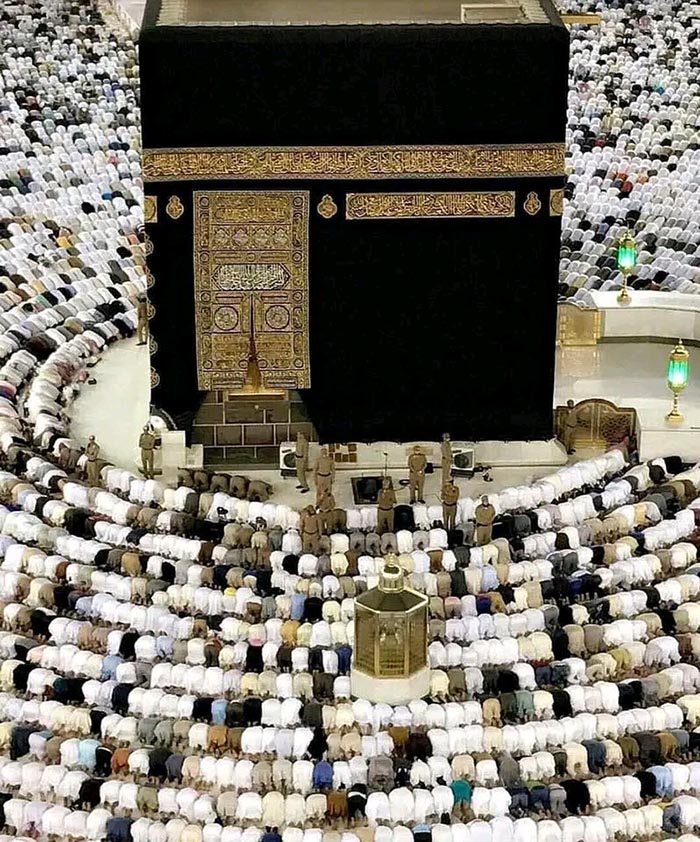

In Mecca, pilgrims orientate themselves towards the Ka’ba in prayer. Within the mystical tradition of Islam, the Ka’ba is symbolic of the heart which is at the centre of our being. Image: via Wikimedia Commons

The Individual and the Community

.

Jane: I completely accept your main message about the need for us as individuals to be working on ourselves and doing what we can to become a place of light in the world. But still it seems to me that in the present global situation, when so much is at stake, there is also a need for collective action. How might that work without contradicting what we have been talking about here?

Eric: Well, at the moment I am actually living in a community for the first time in my life. I am not only a self-taught person, but very much a loner as well, so I have been rather distrustful of people getting together in communes – although a lot of my uncles and aunts were in these kinds of groups in the 1960s, so I understand what drove them.

The interesting things about this particular community, which is a religious one, is that people constantly ask themselves what brings them together. We might start by saying; Well, there is our friendship with one another. Or we feel that we’re brothers and sisters; it’s like a big family. And then we think about our teacher – that we are unified because we have the same teacher. But then our teacher says: You are here because of the spiritual path you have chosen. So then we realise that we are each of us following this path individually, but this also makes us a kind of community. But it is a community formed vertically, not horizontally in the usual way these things happen, by people having a common interest in justice or anti-racism or anti-colonialism or whatever.

So there is a kind of community here and a form of communal action – we use the word ‘we’ when we talk about what we are doing – but for each of us, the focus is always on the vertical dimension, on our own relationship to our spiritual path and our own work.

Richard: When we first began this conversation, I had a fundamental question about this idea that our best course of action in a time of such crisis is to focus on our own responsibilities and be responsible to ourselves. I thought: But I’m just one tiny person amongst billions of others, and I don’t have a voice in Westminster or in Washington or Tel Aviv. And the wars go on. What’s the point? Why should I even bother? Why should I not just close my mind and ignore everything that’s going on and just try and pretend it’s nothing to do with me? But within Ibn ‘Arabi’s perspective, you have explained that what we mean by the ‘individual’ has much deeper dimensions than we normally understand by the word.

Eric: Yes, because if we really understand what Ibn ‘Arabi says about creation and start to grasp the implications of this vertical dimension, then we come to see that one individual is everything. The centre of the universe is going right through our core, and each one of us can be the vehicle for a divine name. When we are operating from that place, then we have clarity. We know what’s happening, and we do what we do because we’re fully present. What happens horizontally is not in my hands, because by myself I cannot influence five shadows, ten shadows, 15 shadows or however many. But the light can influence every one of them. When we are truly present, holding that dying child in our arms and there is no distraction and no outsideness, the light can shine through.

Richard: I know that in this conversation we have only touched on a very small part of Ibn ʿArabi’s comprehensive vision, but what you have brought is nevertheless extremely helpful and thought-provoking. So thank you for agreeing to talk to us about these critical issues.

To learn more about Ibn ‘Arabi, The Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi Society website [/] has a wealth of information not only about his life and work, but current events.

To learn more about Eric’s translation project, see The Futuhat Foundation website [/], which contains recordings of many seminars and lectures on the meaning of the book.

Image Sources (click to close)

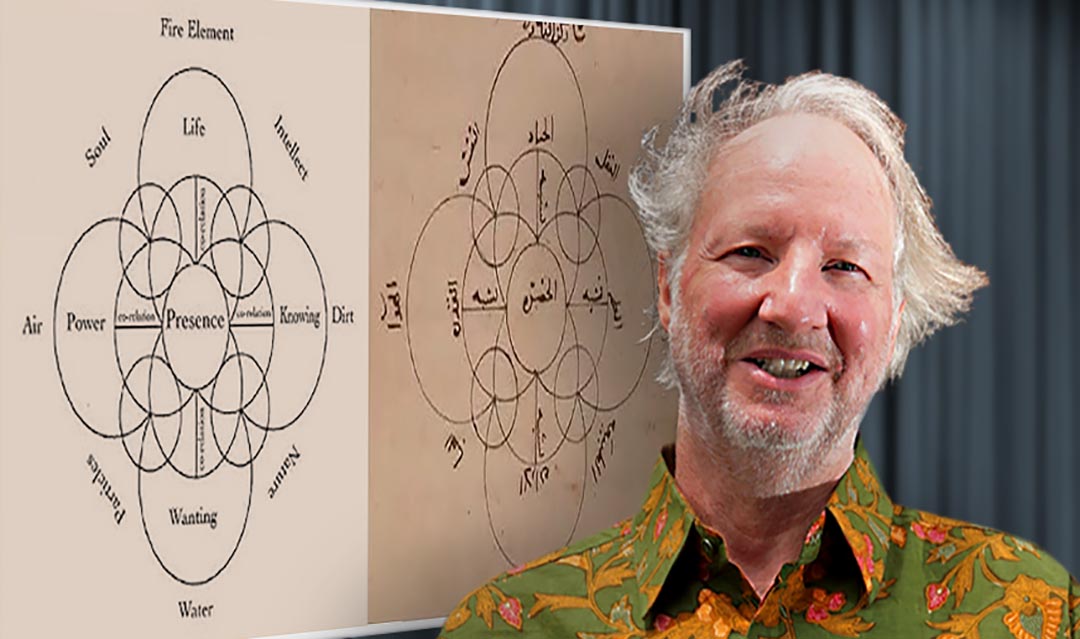

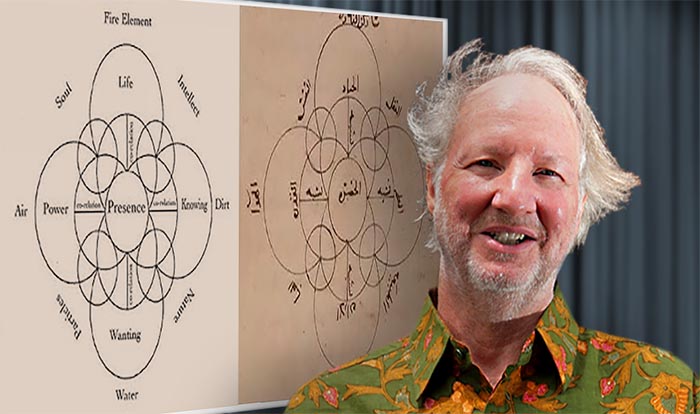

Banner: Eric Winkel in Bandung, Indonesia in 2022. Photograph: Lokamaya. Behind him is a diagram depicting the interaction of the divine names drawn by Ibn ʿArabi in The Openings Revealed at Makkah. Image: Courtesy of the Ibn ʿArabi Society

Inset: The first four volumes of Eric’s translation published by Pir Press. There are will be 19 in the final complete set.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] IBN ʿARABI, The Openings Revealed at Mecca, translated by Eric Winkel, (Pir Press, 2018– ongoing). For information, visit https://www.thefutuhat.com

[2] IAIN McGILCHRIST, The Matter with Things (Perspectiva Press, 2021).

[3] Quran 7:156.

[4] See https://www.abuaminaelias.com/dailyhadithonline/2012/03/08/allah-rahmah-prevails-wrath/.

[5] New Testament, Luke 21, 1–4.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Stefan Sperl: Faces of the Infinite

Stefan Sperl talks about about his project on Neoplatonism and the poetic traditions of Europe and the Near East

The Cosmos in Stone: The Ascent of the Soul

Tom Bree correlates the meaning embodied in the geometry of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and Wells Cathedral in Southern England

Bewildered by Love and Longing

Michael Sells and Simone Fattal talk about a new translation of Ibn ‘Arabi’s famous cycle of love poems Translation of Desires

Rumi: The Operation of Divine Love

Alan Williams tells us about his new translation of Rumi’s great epic poem, the Masnavi

READERS’ COMMENTS

Thank you for your work.

Love to you,

Andrew

Many thanks for this exposition, the “breath of mercy” indeed. Only by releasing the knots of constriction is there the possibility of expansion and the running through of Truth. In some ways the Buddhist path parallels this as an universal path in myriad forms.