Inspire Dialogue Summaries: Conflict Resolution

Brendan Simms, Professor of European International Relations, Director of the Forum on Geopolitics

“We were criticised and ridiculed by other professional groups for coming into a maximum security prison with the word ‘trust’ in mind.”

In our group we started with looking at the root of suspicion and conflict, which of course is fear. Our group was very diverse from the point of view of background and age, but also experience. But everyone had had some kind of direct experience of violence and/or alienation, whether it was working in the prison system, experience of armed conflict, the war on drugs, migration, or schools where fear is endemic. And so we asked: how do we get out of this situation? And we agreed that for this we need trust. But how do we establish trust if it has been broken by a bad experience, or how do you establish it in the first place if we are dealing with strangers? Here again, we had many examples of how tensions were overcome based on experience: for example, of knife violence in a school situation, where the situation was defused simply by advancing physically upon a threatening figure and embracing him. Or, at the other extreme, governmental programmes to integrate groups and reduce barriers in that way.

One of the points that was made is that in order to do this you have to show vulnerability on your own side, in that you have to be able to let your guard down. In the example that was given of the knife attack, this is obvious, but we wondered whether there was some possibility of scaling this up from individuals to states and organisations with a view to better conflict resolution.

The other thing I want to highlight is the matter of timing with both conflict resolution and trust building. If you take the example that I mentioned in my introduction this morning – that of the Thirty Years War in Europe which culminated in the Westphalia Agreement – it is not very encouraging because they had to wait thirty years until everyone was exhausted. The Northern Ireland troubles also lasted decades. And so we wondered whether there was some way of kick-starting the peace process earlier, so that we wouldn’t have to wait until everyone is exhausted – as in, say, the Israel–Palestine conflict. We did not have a particular model about how that could be done, but the question was asked.

Alison Liebling, Professor of Criminology, University of Cambridge

I have been delighted by the conversation about trust today, because of my involvement with a project at a maximum-security prison. I originally studied this prison in the 1990s, but I was asked to go back to it twelve years later because of concerns about radicalisation and risk. We found that the whole place had become paralysed by distrust; in a very short amount of time the prison had changed from being a place where guarded but very real forms of trust were flowing between staff and prisoners, and among prisoners, to it being a place where everyone was afraid of everybody else. Staff no longer recognised prisoners, and the information flow was no longer going on in the wings where the prisoners were living, but off the wings in security information reports.

So we decided to go and study trust. Everyone wanted us to study risk, but we resisted that and went to other maximum security prisons to study trust. We were criticised and ridiculed by other professional groups for coming into a maximum security prison with the word ‘trust’ in mind. But in fact, almost before we arrived at the prison some of the prisoners were waiting for us, excited that we were this important group from Cambridge who were willing to come and talk to them about trust, because nobody else would use the word. And the project has been really valuable: we have learnt all sorts of things about how destructive a lack of trust can be, and how a little bit of trust can build relationships and reduce violence. The prisoners themselves have found it so important to have conversations about trust that they have decided to carry on doing it without us, and they now have a ‘trust committee’. They write us letters; they invite us to their meetings; they invite people from different faith backgrounds to talk to them. The whole point of the dialogue is for them to get to know each other and build trust between themselves. We have seen it make a massive difference not only to the life in the institution, but also to all the individuals living within it.

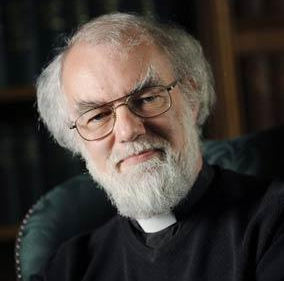

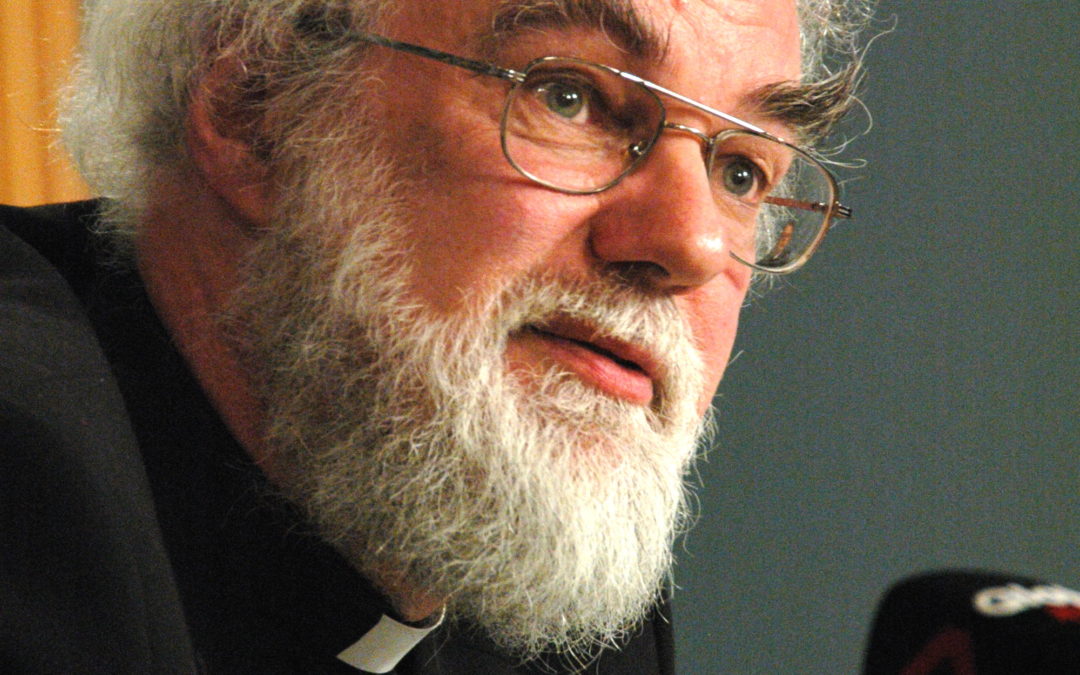

Inspire Dialogue Introductions: Lord Rowan Williams

Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge

“When we go out and encounter others, we are asking for something that is not already there to come alive in us.”

Inspire Dialogue Introductions: Frederick Smets

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR)

“Most of these people do not need money, but they need somebody that they can have a conversation with.”

Inspire Dialogue Introductions: Tawanda Mutasah

Senior Director of Law and Policy for Amnesty International

“The stranger or ‘the other’ is a notion that we construct in our quest for a resource. In reality, there is no ‘other’…”

Inspire Dialogue Introductions: Baraa Halabieh

English-Arabic translator

“What makes humanity so beautiful is our multiculturalism… the variety in our colours, cultures and beliefs is what makes us all unique.”

Inspire Dialogue Summaries: The Environment

Bhaskar Vira

“How do we have a dialogue with someone who is fifty years away from inhabiting this earth? This leads to considerations of inter-generational responsibility.”

Inspire Dialogue: Final Summary

Lord Rowan Williams

“To be able to imagine that things don’t have to be as they are is perhaps one of the most important things that human beings ever do.”

MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE:

Unlocking the Heritage of Tibet

Dylan Esler talks about the ancient contemplative tradition of Dzogchen Buddhism – the ‘effortless path’ – and the 84000 Project, which is preserving the precious heritage of Tibetan Buddhism

‘Once we learn to dissolve that sense of having to react to whatever occurs, then we open up to a more spacious perspective, and that is the perspective of non-duality.’

The Vision of Esalen

Michael Murphy, co-founder of the Esalen Institute in California, reflects on the contribution of an institution that has revolutionised our understanding of spirituality

‘We’re all, whether we know it or not, together involved in a cosmic jailbreak, breaking out of our golden chains.’

Transmission Across Cultures

Writer and art historian Diana Darke brings to light the largely unacknowledged influence of Islamic architecture and craftsmen on the iconic buildings of Europe

‘If you are building a prestige project, of course you’re going to go for the best, wherever it comes from.’

George William Russell: A Forgotten Irish Mystic

Gabriel Rosenstock gives a poetic response to twelve visionary paintings by the ‘myriad-minded’ writer and polymath

‘[Through his works] we may see the world once more in its primal beauty, may recover a sense of the long-forgotten but inextinguishable grandeur of the soul’

Rolling Out the Doughnut

Leonora Grcheva of DEAL talks about how Kate Raworth’s innovative economic theory is being translated into sustainable practice in cities across the world

‘The Doughnut gives us a new way to conceptualise who we are, how we position ourselves as part of the living world, and how we can reimagine our future’

Emily Young: Giving Voice to the Earth

The distinguished sculptor Emily Young talks about her work and the stories that stone can tell us

‘What does it look like when a human is at one with the universe? Embracing it all…’

Richard Lewis: Pilgrim in the Land of Children

Robert Hirshfield appreciates the work of a teacher who has devoted his life to inspiring children to write imaginative poetry

‘A child is the privacy of a universe learning to talk to itself.’

The Power of Gold

Alan Ereira talks about his new book, which traces the relationship between human beings and this most precious metal over a period of 7,000 years

‘The notion that gold contains immutable value is somehow enormously powerful. Of course, gold doesn’t actually have that value in itself; we attribute that to it without thinking, unconsciously.’

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

The Philosophy of Prayer

Distinguished theologian George Pattison talks about the meaning of prayer in the modern world and how it brings us to awareness of our essential nothingness

‘Our starting point always has to be that we are not makers of our own being, but we are before we start doing anything for ourselves.’