Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 26, 2024

This Little Light of Mine

Joy Bostic talks about Africana spirituality and its expression in popular music and dance

This Little Light of Mine

Joy Bostic talks about Africana spirituality and its expression in popular music and dance

Joy Bostic [/] is a scholar and teacher whose work focuses upon the cosmology and aesthetics of Africana spirituality. Director of Africana and African American Studies at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio, her first book, African American Female Mysticism,[1] was a study of three important black women activists – Jarena Lee, Sojourner Truth, and Rebecca Cox Jackson. Her second, due out later this year, is entitled Black Vitality and the Power of Religion and Performance in Popular Music, Dance and Visual Culture.[2] In it, she explores the way in which these forms of expression emerge from a deep spiritual understanding that has been passed down through the generations. She spoke to Jane Carroll and Jane Clark by Zoom about why the understanding of these forms of spirituality and mysticism are important not just for the black community, but for all of us in the contemporary world.

Jane Clark: The main focus of your present work is the way in which the artistic forms of expression that have come out of African American communities – particularly music and dance – are influenced by their specific form of spirituality. You have described this as being characterised by ‘embodiment’ and ‘vitality’. Could you explain what you mean by these terms?

Jane Clark: The main focus of your present work is the way in which the artistic forms of expression that have come out of African American communities – particularly music and dance – are influenced by their specific form of spirituality. You have described this as being characterised by ‘embodiment’ and ‘vitality’. Could you explain what you mean by these terms?

‘Joy: Black spirituality is rooted in an embodied understanding of identity and ways of being. When I say ‘black’, I am referring to what is now called ‘Africana spirituality’ as it was formed by African ethnic religions, and then adapted and reimagined in the diaspora which happened during the years of the slave trade between the 16th and 19th centuries – the United States being just one of many destinations. And when we talk about embodiment, people like the historian and theologian Charles H. Long [/] have talked about this in terms of black cultural productions – meaning, religion, dance, art and music, etc. But it can also be talked about as just a way of being in the world, because certainly the experience that we’ve had within the Americas has been one which has impacted our bodies in a major way.

Some of the earliest religious rituals of black people within the Americas, particularly within the American South, were based on embodied practices that include movement, music, instrumentation, rhythm and improvisation – both individual and collective – and group leadership. One of those rituals is the ‘ring shout’, which was a kind of dance – a counter-clockwise movement – which included an element of call and response from which many scholars believe that work songs and spirituals evolved. Those spirituals were then adapted and reimagined depending upon what was happening in the community, or what was needed by a particular community (see video below for a re-enactment of a ring shout).

Video: Plantation Ring Shout Dance, performed by the Georgia Geechee Gullah Ring Shouters; duration: 3:10

Jane Carroll: And how would you define ‘vitality’?

Joy: The idea of vitality is a reference to the ways in which those embodied rituals become pathways and portals to connecting to a larger reservoir of spirit and ancestral resources. In the black missionary Baptist church in which I was brought up, many of the practices are long-held and have been passed down generationally and adapted. And the songs continue to have great power. When we sing them, when we perform them – and I mean perform in a sense of ritual performance, not the sort of performance where there is a separation between audience and performer – we are charging that space with spirit as well as with the generations that have sung and tapped into those same sources before us.

So by vitality, what I’m talking about is really a kind of mysticism if we understand that as being broadly defined as direct experience of divinity. These embodied rituals which involve movement, gestures, and verbal affirmations, call and response, etc. – all these are strategies that enable us to have an experience, or open the way for the possibility of experiencing spirit.

This Little Light of Mine

.

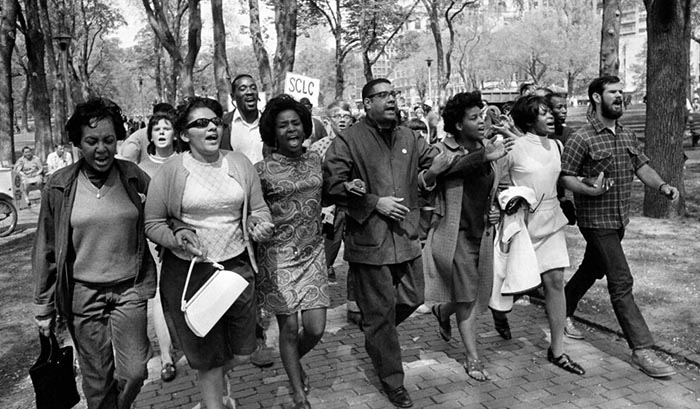

Jane Carroll: One of the areas of your research has been the use of spirituals and congregational songs played during the civil rights movement in the 1960s. Can you say more about that?

Joy: Music played a really important role in the movement. To give an example: Bernice Johnson Reagon, who was one of the Freedom Singers [/], tells a story about a time when a group of members were in a church – I think they must have been in Alabama at that time – and a sheriff came in. They could all sense the power that he was trying to enforce, to create fear. And initially people did become anxious and fearful. But then someone started singing a spiritual and other people took up the song, and this changed the atmosphere. When they began to sing, they found their courage and reclaimed the space from the ways in which law enforcement was trying to take away their power. Bernice Reagon talks about such incidents in the video The Songs are Free [/].

So there’s a shift that happens when the sound of these songs runs through the body – there’s an internal shift, and there’s also an external shift. Internally touching or tapping into that vitality changes or creates a shift or an empowerment that happens within the person, but singing it collectively shifts the external space as well.

Jane Carroll: Reagon, who went on to form the group Sweet Honey in the Rock, has spoken about one of the songs that became a kind of anthem for the movement, ‘This Little Light of Mine’, which has the line: ‘I’m going to let it shine’ (see video right or below). She talks about the power of the ‘I’ – what is happening in the individual, as opposed to the collective statement in another very important song, ‘We shall overcome’.

Video: This Little Light of Mine, performed by Sweet Honey in the Rock and James Horner; duration: 3:20

Joy: One of the features of Africana spirituality is the way in which it can embrace the complexities of interaction between the collective and the individual. In black aesthetics, whether it’s dance or singing or playing an instrument, the two are never separate. There is always a collective structure, but at the same time, there’s room for individual improvisation and individual takes on how people hear or respond. Even if someone is singing alone, the collective reservoir is always present; they are tapping into a larger collectivity of people in the past as well as those present in different geographical locations. But at the same time, they’re constructing individual identity and exercising agency. And so the pronouncement of ‘I’ means, yes, I’m exercising agency, I’m deciding, I’m claiming and proclaiming that I have a light – that I have a sense of self-possession, of who I am and what that light means.

When I was growing up, our elders gave us a platform at a very young age and encouraged us to make speeches and to perform these songs. And because of the call and response nature of black worship, we repeatedly got affirmation back. When we sang, recited texts or performed plays, or marched with the choirs, our elders affirmed our light, ‘our little lights’, and thus that we were children of God, by way of this call and response – ‘Amen’ and ‘Hallelujah’. Even if we were off-key, they would still say: “Amen, baby.” They just would affirm us and understand that we were in the process of development. With these ‘Amens’ and ‘Hallelujahs’, they were proclaiming: you are a person of value and worth and you can do anything. They gave us permission and in fact charged us to assert our brilliance and allow it to radiate everywhere.

And these affirming spaces which they created – in which they transmitted structured wisdom and deep reservoirs of African American aesthetic and ritual – were infused with love.

Jane Clark: Do you think that this emphasis upon the ‘light within’ was intensified because of the need for survival – because there was such oppression and people’s personhood was under such attack during slavery? Could this have increased the need to affirm the sense of the ‘I’?

Joy: No, I think that the collective structures were already there, and they were sustained and adapted in terms of how they were tapped into depending upon what people were facing. The genius of Africana aesthetics and structures is that at their core they’re very adaptable; they are able to travel and to encounter and engage with other cultures. This happened even on the African continent, where there are many diverse ethnic groups. When different ethnic groups or cultures came together or conquered each other, they were able to absorb the deities or even some of the practices of other groups. This is a big difference between how those cultures adapted versus colonialism and Christianity.

And of course, this adaptability was a big feature of the diaspora when people came to what would become America through enslavement and the various forms of voluntary immigration or migration. People from different ethnic groups were thrown together, and what they fashioned was an adaptation of what they brought with them, depending upon the area and which peoples were involved. When we talk about later adaptations of aesthetics and music – the blues and jazz, etc. – we tend to put greater emphasis on peoples’ individual contribution, but still, they continued to be part of a larger collective, and that in turn depended upon where people found ourselves and what they were contending with.

Jay-Z performing in 2008. Photograph: Mike Barry via Wikimedia Commons

The Sacred and the Secular

.

Jane Clark: We have been talking about the music and dance that takes place within a church context, but there are many other forms of black music. You mentioned the evolution of the blues from the call and response traditions, but there’s also jazz, there’s rap and hip-hop, there’s rock and roll. Do you see all of these as springing from the same sort of understanding?

Joy: Absolutely. That’s why I focus in my work on what I call ‘cosmology’, because I think that the structures and the underlying cosmology remain consistent in all these forms of expression, whether we are talking about the sacred or the secular. There is not really a division between them; they are all dealing with the sacrality of the black body – the sacrality of black people. So when Jay-Z says ‘I’m from Marcy’,[3] (see video right or below), which is the housing estate in Brooklyn where he grew up, he’s meaning: where I come from has value and meaning, and the people who live there have value and meaning.

Video: Jay-Z: Where I’m From; duration: 2:38

And when he calls himself J-Hova, which is a play on the Old Testament name of God, Jehovah, he is making a reference to the divinity within. All religions, even Methodism, have some notion of ‘deification’ – the divinisation of the human body. But people don’t always understand this properly. For instance, one commentator, who is not a theologian and so is not trained in these things, has accused Prince of thinking that he is God or Christ. But that actually isn’t what he’s saying. What he’s talking about is this little light that is within us – the divinity within. This is what these singers and musicians are asserting in the midst of a culture and a context that would deny them their very humanity.

Jane Carroll: Can you say more about what you mean by the term ‘cosmology’?

Joy: I’m talking about the underlying ideas and structures that are common to a lot of these African diaspora spaces despite their differences. It is basically the understanding that the invisible and visible worlds coexist. People may not talk about this explicitly, but they will say things like: my mother who’s passed on, she’s still with me. Kendrick Lamar actually does this digitally on his album To Pimp a Butterfly [4] where he has conversation with Tupac Shakur.

Jane Carroll: The rapper from the generation before him, whom he had never met in person?

Joy: Yes. And Tupac says: ‘Sometimes when I’m performing, I don’t know where that comes from. I think it’s the “dead homies” coming through me’. That’s Africana cosmology – the understanding that the dead are still communing with us. It’s always a recognition of the invisible world being about God and divinity, but there are multiple ways that that can be experienced depending upon one’s theology. But in whatever way it happens, it’s about tapping into this reservoir of the invisible world, knowing that it is impacting our present world.

And at the same time, there is the understanding that what we’re doing is for those who are not yet born. So the notion of time is different when you are actually experiencing God as spirit in this invisible realm – when you have these empowerment moments. It’s not linear; there’s a suspension of time. So artists and musicians are always tapping into and signifying on what’s gone before them. In hip-hop, for instance, performers are always signifying and sampling the music from earlier generations, but at the same time moving it forward – moving forward in a different way. We see this in jazz as well, and in dance and movement.

So we understand that there are porous boundaries between these two worlds, and that what’s important is that we’re hearing from the other side, or we’re hearing from God or divinity. Because we all need to hear – to know – that God is showing up in this space, to empower us, to communicate with us, to give us information, to confirm or affirm the divine presence with us. And so that’s what I mean, loosely speaking, by cosmology.

Spirituality and Action

.

Jane Clark: Another striking aspect of black American spirituality is that just as there is no real separation between the sacred and secular, it seems that there is none between contemplation and action. Many leading lights in the civil rights movement have also been pastors and preachers – Martin Luther King Jr, for example, or Howard Thurman [/], who was a scholar and a mystic as well as an activist. The same is true of you, as well.

Joy: I grew up in a missionary Baptist church where my uncle by marriage was a pastor, and also one of the main civil rights leaders within our community. And so there was never a separation between the spirit and what we were learning from our biblical study and how we were taught to engage in the world and give back. We were here to actualise God’s purpose in our lives and our potentiality as we stood for love and justice in the world.

Jane Clark: Can you say more about what you mean by actualising God’s purpose in our lives? This is an idea that comes from Howard Thurman, I believe.

Joy: Thurman identifies the actualising of divine purpose as the materialisation of vitality. So he aligns vitality with purpose and meaning – and not just for human beings, but for all of creation. For him, meaning and purpose are inherent in life. This means that they are involved in the shaping of the self from within, but they are also cultivated while living, discovering and confirming the internal impulse of life specific to each living being. For Thurman, aliveness is about expressing one’s core meaning or purpose in ways that resonate with what he calls ‘the sound of the genuine’. But there’s an inner/outer interplay that is always at work in terms of trying to understand what it means to be authentic in one’s identity and being.

Jane Carroll: I know that you worked with the systemic theologian James Cone [/] in New York, and I am interested how his idea of black liberation theology fits with what you’re talking about.

Joy: Well, while the activity of materialising vitality is in one way an expression that is internally generated, independent of outside influences and constraints, in another way Thurman understood from his own experiences that outside forces may affect this process even to the extent of distorting it and making it a caricature of itself. And so it is that for black people, the oppressive structures and legacies of white supremacy and anti-Blackness, as well as patriarchy and heteronormativity, have erected barriers to what it means to touch the fullness of black vitality and practice aliveness in diverse and complex ways.

In thinking about what Cone said, I would reference another important theologian, bell hooks [/]. What she points out is that when Cone came up with his theological notion of God being black, it was essentially a provocative way of challenging white supremacy. This is something that the rap artists are also talking about quite explicitly, even though these forms of expression can also be entangled with problematic socio-cultural issues. For bell hooks, loving blackness is about affirming black humanity and decolonising the ways in which we think about it. In my case, in the context in which I am working as an academic, this means thinking about theology and God – about the ways in which we need to decolonise the way we think about spirituality, the way that we think about mysticism, and learn to read our culture and our traditions in an open and flexible way which affirms black cosmologies and practices.

Jane Carroll: Is this something that you are doing in your teaching work?

Joy: Yes. One of the problems that we have is that black people themselves have very often internalised colonial ideologies. So even though the black church first introduced me to loving blackness and black cosmological practices as a spiritual embodied social practice, there are ways in which hierarchy and patriarchy, and even anti-black ideologies, can seep into the church setting. So in terms of doctrine and theological language, these same spaces can be entangled with priorities that are in opposition to unleashing the full numinous power held within each of us, and the communal love ethic.

On the courses that I teach, we cover Africana religions, and I always start with Vodou. And I do that because I often have students who come out of Christian traditions whose imaginations are populated with Hollywood versions of voodoo– zombies and so on. This is even though we now understand that while Vodou is practiced in Haiti, originally the Vodun in the Americas were transported from the area of present-day Benin, where in fact Vodou continues to be practiced today. So I use Vodou to push the students outside of those imaginations.

The loving blackness that Jim Cone was speaking of is in a way strictly within a Christian context. But he, as well as Howard Thurman, also affirmed the use of things like idiom and black aesthetics. You know that Cone did work on the spirituals and the blues? [5] So he definitely understood the ways in which embodiment and a lack of a clear delineation between the sacred and the secular doesn’t hold up within these cosmologies.

Because of the strong emphasis on embodiment, Africana spirituality is about life, and freedom, and pleasure, and connection and relationality. All of that is a part of who we are. It’s not only praying in the spirit: it’s the freedom to be able to express oneself in the world. It’s the pleasure of sex. It’s relationship, family, food. Within the Africana religious traditions colour, gesture, adornment, food – all these are expressions of community, relationality, the sacred and the secular, in formal or informal ways.

Video: ‘Boogie Chillen’: John Lee Hooker, with The Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton: Live, 1989; duration: 4:51

Universal Relevance

.

Jane Clark: We’ve been talking about the black community, but these principles are also very relevant beyond it. You have spoken about being brought up with the music of James Brown and Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane, and when I heard you say this I thought: Well, so was I. For the baby boomer generation in Europe, jazz and blues and rock and roll was the music of our youth and it was tremendously important in the development of 1960s and 70s culture. You could say that it set our generation on fire. And this crossing of racial boundaries is even more evident today; singers like Beyonce and Tina Turner are global phenomena; everybody – black, white, Asian, Indian, deepest African – loves them.

Joy: There are two things I can say about this. One is that an important part of my work is to help my students, who come from all sorts of different cultural backgrounds, to understand the cosmologies and the histories that are behind this music and how it’s constructed, so that when they are consuming it, they know something of what they are participating in. Therefore, they are able to value, understand and affirm where it comes from, not just appropriate it in ways that can be quite negative.

But the other thing is that this matter of decolonising is important for the white community as well as for Black people. Because we are all living under, and trying to navigate our way out of, patriarchal, colonial constructs. There’s a reason why there are theological formulations, legal constructions, that alienate us from our body. And there are reasons why this alienation is part of the institutional constructs which are being perpetuated.

For instance, as women, during both your growing up and my growing up, we were in spaces where our body was a precarious site and the way our body moved in the world was an issue. It was the same for James Brown or Sam Cooke when they were performing for white teenagers. There were a lot of tensions at that time associated with black performers: how black bodies were used, how these artists were still moving in spaces of segregation. Also the ways in which white artists adapted their creative methods and how the industries rewarded white artists versus black artists. So the situation was entangled and messy – complicated.

Jane Clark: It is also interesting to see how hip-hop in particular has become a kind of universal language of dissent across the world. The Iranian rapper Toomaj Salehi, for instance, is currently facing a death sentence because of a song he wrote.

Joy: Yes, I think it is important to see the ways in which the black freedom movements in the US have influenced so many other movements – the women’s movement, gay rights movement initially moving into LGBTQ, etc. – not only in the US but around the world. In loving blackness and decolonising our theologies and ideologies, all of us – black and white – are meeting each other and honouring each other. Kevin Quashie talks about this in his book Black Aliveness;[6] that we need to meet each other and engage with one another in mutually affirming ways. That’s the work. Both to celebrate and to understand what we’re celebrating, and then critique and deconstruct those structures and constructs that would diminish or demean, marginalise or exploit us.

Love as Radical Action

.

Jane Clark: You’ve mentioned the feminist theologian, bell hooks. Her most famous book is all about love,[7] and in that, she talks not just about loving blackness, but love in a universal sense. She sees love as a radical action. What would you say about this?

Joy: Well, first I would say that within the structures that we find ourselves, the radicality of loving is because it is fundamentally an act of risk. It is an act of risk in terms of making ourselves vulnerable. Going back to the connection between the ‘I’ and the ‘we’, it requires a strong foundation and a sense of self that can maintain its own groundedness to risk the vulnerable act of loving. And for this reason I’m always concerned when talking about this in situations where people – black people specifically – are facing acts of violence and people are asking them to love and forgive. That’s actually an abuse, an exploitation. We can’t demand that from someone in a moment of crisis. If I am to make myself vulnerable, it has to be as someone who can afford to take a risk because I’m standing, rooted and grounded, in a deep reservoir of love from all that I’ve learned and taught.

But love also is a radical act in the sense that it involves engaging in the act of deeply seeing one another. The way that we are in culture now, with book bannings and the rewriting of history and so on, has the effect of de-empathising us, so that we can’t see each other and meet each other in deep and engaging ways. So loving is a radical act within cultures around the world where we are navigating systems that are meant to control and to exploit our energies and gifts, and which are designed not to leave us much in terms of how we deeply engage one another. Because when we deeply engage and see one another, then we will act differently politically, spiritually and relationally. This is what Martin Buber says when he talks about the I-thou relationship.

So for me, loving radically is about meeting and being met, and deeply engaging in ways that are honest and earnest, even when we disagree. As opposed to being defensive or triggered out in the sense of being attached to an ideology which is about perpetuating these controlling structures. Rather, I’m seeing you, we’re seeing each other, face to face. There’s risk involved in engaging in that way and sustaining it, and choosing to use our agency in ways that are consistent with it.

So loving is radical in the sense that it shapes the way we use our power. And if we’re loving radically, we can’t use our power over and against. We use our power with and because.

Jane Clark: I think that it is a wonderful note to end on. Joy, thank you so much for speaking with us. We look forward to your book when it comes out later this year and wish you all the best in your very valuable work.

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: Beyonce in performance in the half time show of Super Bowl 2013 between the Baltimore Ravens and the San Francisco 49ers in New Orleans, February 2013. Photograph: © Dan Anderson/ZUMAPRESS.com/Alamy Stock Photo.

Inset: Dr Joy Bostic. Image courtesy Joy Bostic.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] JOY BOSTIC, African American Female Mysticism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

[2] JOY BOSTIC, Black Vitality and the Power of Religion and Performance in Popular Music, Dance and Visual Culture change font size(Routledge, 2024).

[3] JAY-Z, ‘Where I’m From’, from his album In My Lifetime, Vol. 1. (1997).

[4] KENDRICK LAMAR, To Pimp a Butterfly (2015).

[5] JAMES CONE, The Spirituals and the Blues (1972: Orbis Books, 1992).

[6] KEVIN QUASHIE, Black Aliveness, or A Poetics of Being (Duke University Press, 2021).

[7] BELL HOOKS, all about love (Harper Collins, 2001).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: This Little Light of Mine, performed by Sweet Honey in the Rock and James Horner; duration: 3:20

Video: Jay-Z: Where I’m From; duration: 2:38

Video: ‘Boogie Chillen’: John Lee Hooker, with The Rolling Stones and Eric Clapton: Live, 1989; duration: 4:51

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Love Will Not Be Idle: Mysticism and Activism

Jane Clark reports on a conference put on by the Mystical Theology Network in March this year, and talks to its organiser, Dr Louise Nelstrop

Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

Jane Carol visits a new memorial which aims to heal a dark period of American history

Connecting with the Unseen World

Kira Perov, wife and long-term collaborator of the video artist Bill Viola, talks to Jane Carroll about the ideas and experiences which inspire their work

Participating in the Divine Playfulness

Hina Khalid explores the Theological Aesthetics of Rabindranath Tagore

READERS’ COMMENTS

Thank you so much for this article/interview. This is so very important to hear.

It’s truly wonderful work that you are doing with the explorations in the magazine.

Walking the talk – contemplation and love in action.