Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 11, 2018/19

Connecting with the Unseen World

Kira Perov, wife and long-term collaborator of the video artist Bill Viola, talks to Jane Carroll about the ideas and experiences which inspire their work

CONNECTING WITH THE UNSEEN WORLD

Kira Perov, wife and long-term collaborator of the video artist Bill Viola, talks to Jane Carroll about the ideas and experiences which inspire their work

Bill Viola is one of the pioneers of video as an artistic form, and for the past forty years his powerful, innovative installations have been exhibited and acclaimed throughout the world. His work vividly explores the perennial issues of human existence – birth, death, rebirth, grief, frustration, the search for a reality beyond the temporal – drawing upon his deep knowledge of the world’s spiritual and mystical traditions. On the occasion of a major exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, entitled ‘Bill Viola/Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth’ we ask his partner, Kira Perov, about the extraordinary body of work they have created.

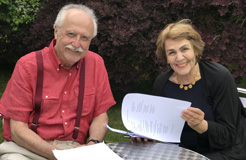

Bill Viola and Kira Perov have one of the great collaborative partnerships in the art world. They met in 1977, when she was working as cultural director at La Trobe University in Melbourne, and he was a young artist, just starting out but already making a name for himself with visual media. They fell in love and have been together ever since. For many years she has been executive director of the Bill Viola Studio, organising the production of the large scale installations for which they have become famous, as well as setting up and curating their many exhibitions worldwide. A respected photographer in her own right, she has also documented the evolution of the work and edits all the publications and catalogues.

Bill Viola and Kira Perov have one of the great collaborative partnerships in the art world. They met in 1977, when she was working as cultural director at La Trobe University in Melbourne, and he was a young artist, just starting out but already making a name for himself with visual media. They fell in love and have been together ever since. For many years she has been executive director of the Bill Viola Studio, organising the production of the large scale installations for which they have become famous, as well as setting up and curating their many exhibitions worldwide. A respected photographer in her own right, she has also documented the evolution of the work and edits all the publications and catalogues.

Kira has co-curated the current exhibition at the Royal Academy, working with lead curator Martin Clayton, Head of Prints and Drawings at the Royal Collection Trust, which has lent 12 of the 14 Michelangelo drawings in the exhibition. So how does she see this juxtaposition of these two artists, working in very different media 500 years apart? “As Martin says, it’s not meant to be a comparison in any way. The exhibition is entitled ‘Life Death Rebirth’ and it is arranged around these themes. You sense with both artists the notion of rebirth. There is always resurrection, transformation, transfiguration. They are both asking: ‘What is this life? How am I going to pass through it? And how will I end it?’”

Bill Viola: The Raft (2004). Video/sound installation. Photograph: Kira Perov

Exploring the Human Condition

.

Kira agrees with the suggestion that the great theme which unites these two very different artists is an exploration of the way in which the spirit appears in bodily form. “But there is also the emotional side. These images all portray deep interior experiences that the people are passing through.” Nearly all of Bill’s works feature people, and as such, they are all about the human condition. This is so whether they are depicting a dramatic event like the transition into death – as in massive installations like Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall) (2005); or Fire Woman (2005), where the figure gradually dissolves into the elements of water and fire – or quieter moments of contemplation, as in Man Searching for Immortality/Woman Searching for Eternity (2013), where two ageing figures emerge out of stone to slowly and thoroughly examine their bodies with small torches.

Another moving work, exhibited at the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery in 2016, The Raft (see video on the right or below) examines the impact of catastrophic events upon us. Produced originally for the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens, it depicts a diverse crowd of people being engulfed, knocked off their feet, by great blasts of water. The action unfolds in extreme slow motion – it is ten minutes long, although the actual event took place within a minute – allowing for detailed examination of people’s responses as their world is overturned.

This emphasis upon the human being is true, says Kira, but there are exceptions: “Early on there was a small candle piece, called Eclipse, in which Bill set a candle in a window, recording the moon slowly entering its frame, moving toward the candle so that the two lights – the cosmic light and the candlelight – merged. There is no person in the scene but in the background Bill is there, moving around making little noises, so you know that someone is in the room, witnessing the event.”

Bill Viola: Walking on the Edge (2012), one of The Mirage series, courtesy the artist and Blain Southern [/]. Photograph: Kira Perov

Connecting with the Unseen World

.

At the beginning of his career, Bill turned the camera on himself while he performed simple actions in creating his videos. “This was in 1972–73,” Kira tells me, “and he was not just performing. The recorded action was slowed down and played and copied, played and copied, until the image began to disintegrate. He was asking: ‘at what point as you disintegrate are you no longer a human being?’” Later, he found he needed to direct and to stay behind the camera in order to develop carefully orchestrated scenarios, either in the studio or on location, such as in his Mirage series in which figures approach each other, and the viewer, across vast landscapes, emerging out of the haze.

But what has remained constant is the desire to explore the limits of physical form – the point, you could say, at which ‘the two lights merge’. In an interview with the poet and critic Lewis Hyde in 1997, he said:

There is something above, beyond, below, beneath what’s in front of our eyes, what our daily life is focussed on. There’s another dimension… that can be a source of real knowledge, and the quest for connecting with that and identifying that is the whole impetus for me to cultivate these experiences and to make my work. And, on a larger scale, it is the driving force behind all religious endeavours. There is an unseen world out there and we are living in it. (The Unspeakable Art of Bill Viola, page 69).

In interviews over the years, he has spoken about two seminal experiences which brought him to this realisation. One was the death of his mother in 1991, when he was at her bedside with his brother. “It was the most beautiful thing I have even seen in my life,” he was to say in Cameras are Keepers of the Souls (see video on the right or below). “It was profoundly beautiful, profoundly sad, and mysterious beyond belief. How is such a thing possible?” In the Nantes Triptych, which is displayed in the RA exhibition, Bill went on to use footage of his mother a week before she passed away.

The other was a childhood experience when he was six years old and fell into a lake. As he reached the bottom, he witnessed a completely different world of colour and sound, which he found overwhelmingly beautiful.

Left: The Greeting (1995) by Bill Viola. Video/sound installation. Photograph: Kira Perov. Right: The Visitation (1528–9) by Jacopo de Pontormo. Photograph via Wikimedia Commons

Adding the Dimension of Time

.

Apart from these very personal experiences, what would Kira say were the main influences in Bill’s work? “He can be inspired by anything,” she responds. “We are in awe of the cave paintings in places like Lascaux or Chauvet in France, or by Aboriginal art. We spent five months out in the south-west United States exploring petroglyphs and pictographs, and ancient dwellings. The beauty and stillness of a temple in Japan, or the intensity of the interior of a monastery in Ladakh, can create the most profound emotional experiences.”

Renaissance art has been particularly important because Bill spent a year and a half in Florence when he first left art school in the early 1970s. She says: “Florence is the Renaissance – really, all of it: the buildings, the interiors, the frescoes, the paintings. But at that time Bill was not consciously interested in all that, because he was working with contemporary artists, and this is what you do when you are young: he was involved with the newest of art’s medium, and immersed in the avant-garde.”

But later on, as they visited collections in museums like the Prado, the National Gallery in London or the Art Institute of Chicago, he began to understand the significance of these paintings. “It is when you begin to use the art that it becomes powerful”, says Kira. “Then when his mother died, he really started to make a connection with these works; they portrayed a deep humanism in depicting the emotions.” The desire to bring this ‘embodied emotion’ (as John Hanhardt has called it) into a contemporary context can be clearly seen in works such as The Quintet of the Astonished (2000), which takes its inspiration from Hieronymous Bosch’s Christ Mocked (The Crowning with Thorns) (see video on the right or below) and The Greeting (1995), which is based upon Pontormo’s 16th-century painting The Visitation.

Another very formative period was the time Bill and Kira spent together in Japan in the early 1980s, where they studied under a Buddhist teacher, Master Daien Tanaka. One of the aspects of Renaissance art which had engaged Bill was the discovery of perspective; he saw that the development of ‘lines of sight’ meant that a picture was seen from a particular point of view, and therefore the viewer became a kind of participant in the creation of the image. In Japan, he realised that video had the potential to bring in the added dimension of time, and thus capture something of the constant fluidity of experience. He read the great Zen master Dogen, founder of the Soto School of Zen Buddhism, who – in his great compendium Shobogenzo: The Eye and Treasury of the True Law – asks that we “see each thing in this world as a moment in time”.

“Bill was incorporating his explorations of the manipulation of time, and light and sound, before we lived in Japan,” Kira explains, “but afterwards there are definitely pieces which show the influence of our stay there. One of Japan’s most notable art forms, the Noh play, uses the slow extending of time in a gradual unveiling of the narrative until everything is revealed finally in the end. The masked performers express their emotions through sound, their voices singing behind the masks.” Later on, in 1987, Bill created a work that is approximately seven and a half hours long, stretching a quickly edited 23-minute sequence of a child’s birthday party until the action moved frame by frame.

Bill Viola: Ocean Without a Shore (2007). High-definition colour video triptych. Installation view, Chiesa di San Gallo, Venice, Italy. Photograph: Thierry Bal

Location and Contemplation

.

Out of all this, the format of the later pieces, with their slowly unfolding sequences, emerged. “What became clear, really, was that the point of a journey is actually the journey itself. So in our work, you have to wait a long time and watch things develop, because you have to go through the experience. This is what Bill is trying to express: the direct experience of something. These video works give us the gift of time. They give the viewer time to spend with these images, to move from our physical ‘real’ world to a metaphysical one.”

It is notable that many of these works have been shown in sacred places, particularly churches and cathedrals. Two of their more recent pieces, entitled Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water) (2014) and Mary (2016) (see video on the right or below), have been installed permanently in St Paul’s Cathedral in London, whilst the The Messenger (1996) was originally commissioned for Durham Cathedral, and An Ocean Without a Shore (2007) was first shown in the small 15th-century Church of the Oratorio Gallo in Venice (see video on the right or below).

Such pieces benefit from being set in sacred structures where the surrounding space has been created for long and quiet contemplation. For Kira, it is as if “a special resonance is created between the works and the environment that informs not only the work, but gives new life to the building”.

Bill Viola: Fire Woman (2005). Video/sound installation. Photograph: Kira Perov

Actualising an Idea

.

I am curious about the process by which a piece comes into being. Where does the original idea come from? Kira makes reference to the extraordinary range of Bill’s reading: “He has read everything: St John of the Cross and the Christian mystics; Rumi and Ibn ‘Arabi; the Japanese death poems. Somebody gives him something to read, and all of a sudden a whole new world opens up. A line can inspire a whole piece.”

One of the distinguishing features of a Bill Viola video is that, although it may be edited or the direction of time reversed (so that water runs upwards rather than downwards, for example), the images are not manipulated with any kind of post production ‘trickery’. They aim to be an authentic record of the event. This is the case even with very dramatic scenarios, such as Fire Woman (2005) in which the performer, a stunt-woman, was so close to the wall of flames that she had to wear flame-retardant clothing treated with fire-proof gel.

The use of the elements – earth, fire, air, water – is a very striking feature of their work. Particularly notable is the use of water to represent the unseen world, beyond the physical. In The Dreamers (2013) (see video on the right or below), for example, seven large screens depict people lying, eyes closed and at peace, underwater at the bottom of a streambed, immersed, it is suggested, in the ‘other world’ of the imaginative presence.

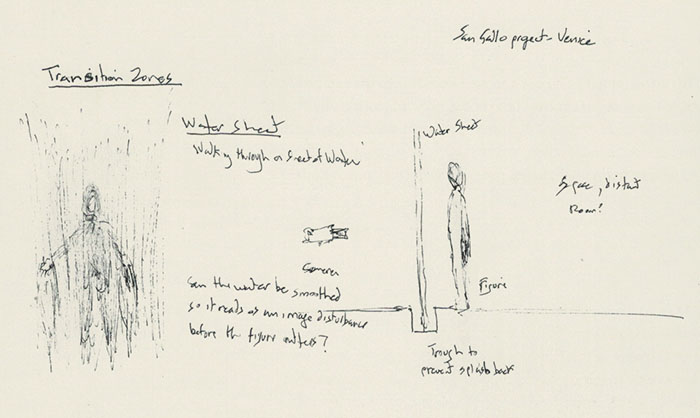

Bill Viola: Drawings for Ocean Without a Shore, Sketchpad, February 17, 2007

Creating An Ocean Without a Shore

.

A good example of their creative process is the 2007 triptych, An Ocean Without a Shore (see video on the right or below), which is based upon a short quote by Ibn ‘Arabi [/] in his Meccan Revelations: “The self is an ocean without a shore. Gazing upon it has no beginning or end, in this world or the next.” Exploring the intersection between life and death, the work documents the movement of a succession of individuals slowly approaching out of the darkness and moving into the light in order to pass into the physical world. Once incarnate, however, they realise that their presence is finite, so that eventually they must return to where they have come from.

So how do they transform the idea into the final piece? “Well, Bill spends a good deal of time reading, then writing up ideas, and after that he makes some drawings. He presents them to me and we discuss which ones should be produced. To me it is usually clear, and I feel them or see an image. Often it is clearer to me than to Bill what the images represent.” They then begin planning different ways of achieving the effect, which is when they bring in a team of professionals.

An Ocean Without a Shore is about a transition, crossing over from one world to another. “So Bill was trying to solve the way this threshold could be depicted by using smoke, veils or a thin sheet of paper. One member of our team had recently worked on a commercial where they were using a wall of water and we found that this was perfect.” The water flowed over a very sharp metal edge that created an effect like sheer, smooth glass. Like glass, it was not visible until it was touched, and then lit by light.

The piece was also innovative in other ways. “It was recorded at the same time with two cameras, fixed with a mirror in between to adjust for parallax, so when the performer was walking towards the water, the images from the black and white grainy camera were used, and after they pierced the water the image changed to the high-definition colour camera. A whole series of works, including An Ocean Without a Shore, entitled Transfigurations, were created this way.”

Most of the time Bill and Kira use actors for their set pieces, but in the case of the Transfigurations series friends and relatives were also co-opted. “For this video, we could not shoot a person or people twice. The scene had to be done in one take so that the response was fresh. A non-actor would not be able to repeat their emotional experience, so for that reason we did not show anyone what was happening – they were simply informed that they would be walking through a wall of warm water.”

But Bill did talk to every participant beforehand, and asked them to remember some kind of experience they had had of making a transition. “So many of them had worked out beforehand how they were going to react as they crossed the threshold; but once they passed through the water, all that fell away as they responded to the deeply emotional event.”

Kira tells me that although they plan these productions very carefully, when collaborating with others they never know what is actually going to happen. “It always seems as if, in the end, the pieces make themselves. When you put all these people together, and they are in tune with the idea, then there is a moment when the work is created: and everyone knows that it has happened and there is a kind of silence in the room – a sense of something profound taking place.”

Bill Viola: Angel at the Door (2013). Courtesy the artist and BlainSouthern [/]. Photograph: Kira Perov

The Power of Images

.

One of the obvious commentaries on the moving image is its role in our modern society, when we are constantly being bombarded with visual material that attempts to manipulate our vision and our emotions for limited ends. Bill and Kira are aware of the challenges presented by their choice of media, but they feel that it is important to understand it properly. As Bill said in an interview in Flash Art in 2003: “We are in a situation culturally now, whereby people who have created this huge machine which is inundating us, flooding us with images… have no knowledge or awareness or understanding of the real effect those images are going to have on us.”

He also points out the potential expansion that these new technologies represent, particularly as regards self-knowledge: the understanding that what we see in the outer world is a reflection of our inner selves. He refers back to the Zen wisdom of Dogen, who maintained that, “The way the Self arrays itself is the form of the whole world”, saying:

Media technology is not at odds with our inner selves but in fact is a reflection of it. These technologies are extending our senses out into the world, literally across space and time… They are being modelled not on the material world of stones and trees and physical objects but…from the functioning of our inner selves – the electric impulses of our brains and central nervous system, the visual receptors of our eyes… (Presence and Absence, page 7).

For Kira, it is, in the end, the content of the works that matter, and the great existential questions that they pose:

These questions don’t belong to Bill or to myself – they belong to everybody. That is the reason these works are universal. Anyone can see them and recognise something, and they realise they can reflect on something they don’t reflect on in their normal life. (Kira Perov, 2019).

Bill and Kira in their studio. Photograph courtesy Bill Viola Studio

Image Sources and Full Picture Credits (click to open)

Banner picture: Bill Viola and Kira Perov in front of the permanent video installation Martyrs (Earth, Air, Fire, Water) (2016) at St Paul’s Cathedral in London, UK. Photograph: ukartpics [/] / Alamy Stock Photo.

First insert picture: A single screen from The Dreamers: Madison (2013), courtesy the artist and BlainSouthern [/]. Photograph: Kira Perov.

The Dreamers (2013): Video/sound installation. Seven channels of colour high-definition video on seven plasma displays mounted vertically on wall in darkened room; four channels of stereo sound. Room dimensions: 21.3 x 21.3 x 11.5 ft (6.5 x 6.5 x 3.5 m). Continuously running. Performers: Gleb Kaminer, Rebekah Rife, Mark Ofugi, Madison Corn, Sharon Ferguson, Christian Vincent, Katherine McKalip.

The Raft (May 2004): Video/sound installation. Colour high-definition video projection on wall in a darkened space; 5.1 channels of surround sound. Projected image size: 156 x 88 in. (396.2 x 223 cm). Room dimensions: 29 ft 6 in. x 23 ft x 13 ft (9 x 7 x 4 m). Running time: 10:33 minutes. Performers: Sheryl Arenson, Robin Bonaccorsi, Rocky Capella, Cathy Chang, Liisa Cohen, Tad Coughenour, James Ford, Michael Irby, Simon Karimian, John Kim, Tanya Little, Mike Martinez, Petro Martirosian, Jeff Mosley, Gladys Peters, Maria Victoria, Kaye Wade, Kim Weild, Ellis Williams.

Walking on the Edge (2012): Video/sound installation. Colour high-definition video projection on plasma display mounted on wall. Size: 36.4 x 61.2 x 5 in (92.5 x 155.5 x1 2.7cm). Running time: 12.33 minutes. Performers: Kwesi Dei, Darrow Igus.

The Greeting (1995): Video/sound installation. Colour video projection on large vertical screen mounted on wall in darkened space; amplified stereo sound. Projected image size: 9 ft 3 in. x 7 ft 11 in. (2.8 x 2.4 m). Room dimensions: 14 x 22 x 25 ft (4.3 x 6.7 x 7.6 m). Running time: 10:22 minutes. Performers: Angela Black, Suzanne Peters, Bonnie Snyder.

Ocean Without a Shore (2007): High-definition colour video triptych, two 65-in. flat panel screens, one 103-in. screen mounted vertically; six loudspeakers (three pairs, stereo sound). Room dimensions: 14 ft 9 in. x 21 ft 4 in. x 34 ft 5 in. (4.5 x 6.5 x 10.5 m). Continuously running. Performers: Luis Accinelli, Helena Ballent, Melina Bielefelt, Eugenia Care, Carlos Cervantes, Liisa Cohen, Addie Daddio, Jay Donahue, Howard Ferguson, Weba Garretson, Tamara Gorski, Darrow Igus, Page Leong, Richard Neil, Oguri, Larry Omaha, Kira Perov, Jean Rhodes, Chuck Roseberry, Lenny Steinburg, Julia Vera, Bill Viola, Blake Viola, Ellis Williams.

Fire Woman (2005): Video/sound installation. Colour high-definition video projection; four channels of sound with subwoofer (4.1). Projected image size: 19 ft x 10 ft 8 in. (5.8 x 3.25 m). Room dimensions: variable. Running time: 11:12 minutes. Performer: Robin Bonaccorsi.

Angel at the Door (2013): Colour high definition video large projection on wall; stereo sound. Size: 85 x 151 in (215.9 x 383.5 cm). Running time: 13.29 minutes. Performers: Carl Henry, Gerald Monroe.

Other Sources (click to open)

RONALD BERNIER: The Unspeakable Art of Bill Viola, Oregon: Pickwick Publications, 2014.

Cameras are Keepers of the Souls, a 28-minute video in which Bill talks about his early formative experiences. Click here [/] to watch.

CLAYTON CAMPBELL: “Bill Viola: The Domain of the Human Condition”, interview in Flash Art 36/229 (2003), pp. 88–91, quoted in Ronald Bernier: The Unspeakable Art of Bill Viola, p.8.

SARAH COMPTON: “Kira Perov: the ‘guardian angel’ in Bill Viola’s life and work”, in The Art Newspaper, 2019). Click here [/] for full text.

JOHN G. HANHARDT: Bill Viola, edited by Kira Perov, London: Thames and Hudson, 2015.

Master Dogen’s Shobogenzo, translated by Gudo Nishijima and Chodo Cross, Booksurge Publishing, 2006.

BILL VIOLA: “Presence and Absence: Vision and the Invisible in the Media Age”, in: The Tanner Lecture on Human Value, Utah, 2007). Click here [/] for full text.

Bill Viola: The Raft (2004). 10:22 minutes

Bill Viola: Cameras are Keepers of Souls. 28:02 minutes

Bill Viola: The Quintet of the Astonished. 1:59 minutes.

Bill Viola: Mary and the Martyrs. 1:12 minutes

Bill Viola: The Dreamers. 8:22 minutes

Bill Viola: Ocean without a Shore. 6:03 minutes

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Bill Viola: The Raft (2004). 10:22 minutes

Bill Viola: Cameras are Keepers of Souls. 28:02 minutes

Bill Viola: The Quintet of the Astonished. 1:59 minutes.

Bill Viola: Mary and the Martyrs. 1:12 minutes

Bill Viola: The Dreamers. 8:22 minutes

Bill Viola: Ocean without a Shore. 6:03 minutes

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Bewildered by Love and Longing

Michael Sells and Simone Fattal talk about a new translation of Ibn ‘Arabi’s famous cycle of love poems Translation of Desires

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments