Understanding Strangers

Jane Clark reports on Inspire Dialogue 2016

UNDERSTANDING STRANGERS

Jane Clark reports on Inspire Dialogue 2016

“There is no other alternative to solve problems other than talks. This should be the century of dialogue to attain peace…”

– His Holiness The Dalai Lama, 2015

These words encapsulate perfectly the motivation which underlies this far-sighted project, which in September brought together an extraordinarily diverse group of people from all walks of life, cultures and generations – the youngest delegate was just nine years old! – for a day of conversation and interaction in the beautiful setting of Magdalene College, Cambridge.

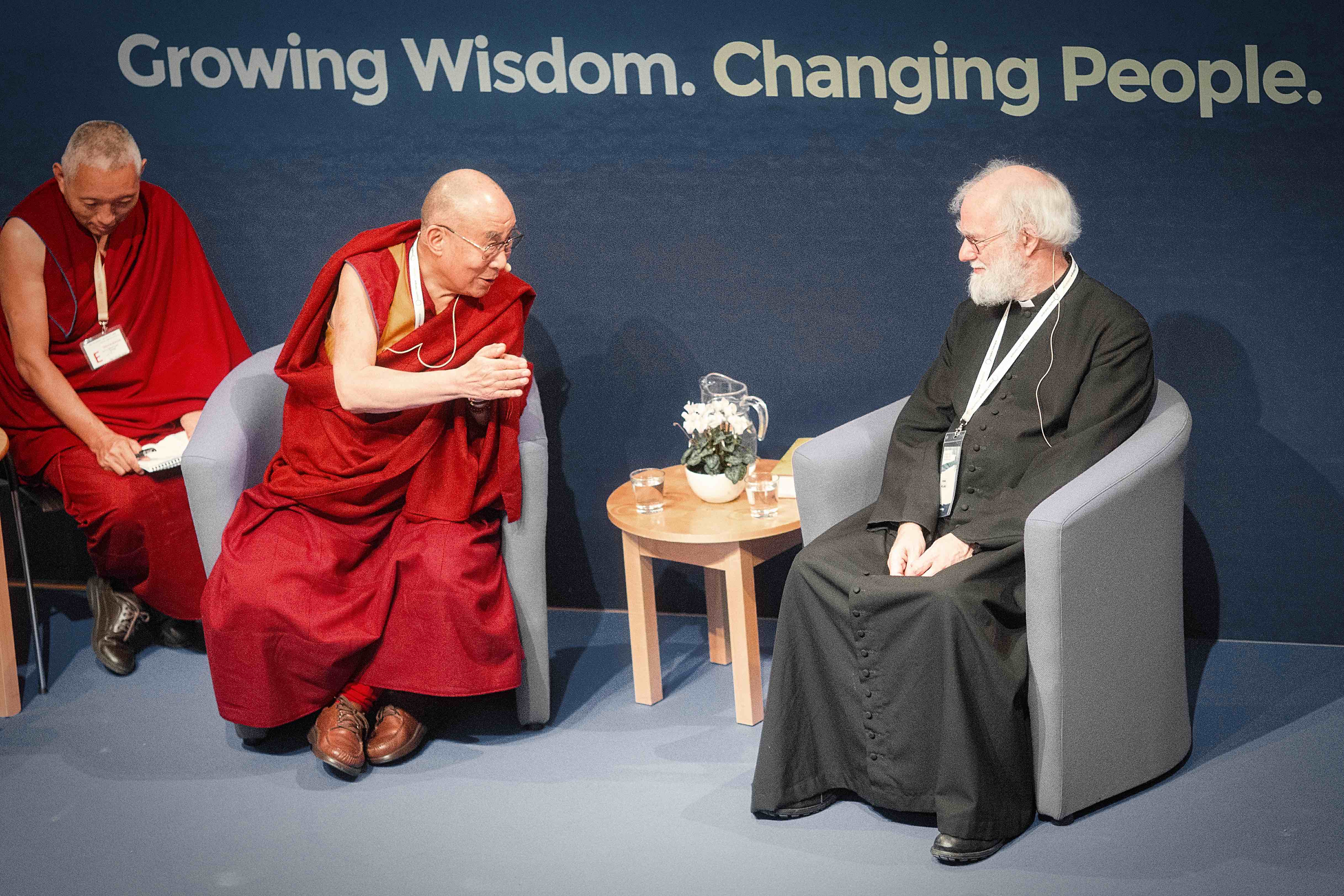

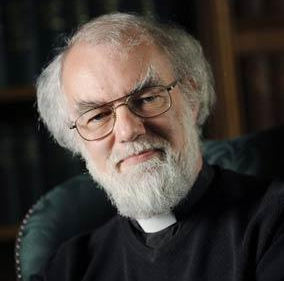

This was the second such event. The first took place last September when Lord Rowan Williams invited the Dalai Lama and 150 others to gather for a dialogue on the theme of ‘Universal Responsibility’ (video) – a theme close to the Dalai Lama’s heart. The energy and the excitement that was generated by that conversation inspired the setting up of a permanent organisation, The Inspire Dialogue Foundation to continue the experiment. This year’s theme – ‘Understanding Strangers’ – grew naturally from last year’s conversation, where interdependence and the fact, as the organiser Cameron Taylor put it, that “We are essentially a human family whether we recognise it or not”, emerged as guiding principles.

This year the dialogue was again convened by Rowan Williams, and as before, it had the explicit aim of bringing together people who would not normally talk to one another, intending to create an informal, open, non-hierarchical ‘flat world’ where everyone came as an equal. The invited guest list of 140 people included senior members of the armed forces and government; activists from international organisations such as Amnesty International and the UN High Commission for Refugees; academics working in universities; headmasters and school-teachers; environmentalists, scientists, people from the arts and business, as well as schoolchildren, students and former gang leaders from inner-city London. Many people brought personal experiences of what it is like to be an immigrant or an asylum seeker in a land with an alien culture.

Much of the day was devoted to conversations taking place within groups based on particular themes – education, technology, environment, freedom, health, conflict resolution, resources. As such, it is impossible to report the event in detail, as any one person could participate in only a tiny fraction of the whole. Here, we can present only a few short extracts from the presentations given at the plenary sessions – the first in the morning setting the scene, the second at the end of the day summarising the group discussions. What cannot be conveyed by these is the atmosphere, which was truly one of openness in which, for example, a young Sudanese woman from an outer-London suburb was given as much attention as a professor at the university. Nor can these excerpts encapsulate the wide range of ideas which were explored as this huge multicultural group worked together to face up to some of the most pressing issues of our day with compassion and goodwill. But they will perhaps give a taste of some issues that were raised.

But first, I would like to make a couple of observations. Underlying all that went on was the question of dialogue, and why it is so important in the present day. In an excellent paper issued as part of the preparatory reading for the event, Robin Kirkpatrick, Emeritus Professor of Italian and English Literature at Cambridge, asked whether a comparison can be made between dialogue and the act of translating a literary text such as Dante’s Divine Comedy from Italian to English. He pointed out that when translating such texts, there is a clear need for a “careful response to the details of language”, because the complex array of meanings of a word in one culture may not allow for its simple transposition to another, even when exact equivalents seem to be available. The meaning of French word honnête, for example, is not the same in every respect as the English ‘honest’.

Without awareness of these issues, translation can lead to “dangerous, potentially tragic” misunderstandings. But with awareness, Professor Kirkpatrick argues, it can actually lead to a closer engagement between participants:

“In recognising the possibility of misunderstanding, or even of radical disagreement, a certain courtesy may reveal itself and be seen as the condition of all dialogue or indeed as a source of conversational pleasure…

One may be impelled to exercise in new ways the resources of one’s own native language. Thus the opportunity opens up for, precisely, an attentive engagement – which might indeed be described as a form of courtesy – where the original text, the translation and even the critical reader may come to be involved in a continuing discussion.”

Applying this to the action of intentional dialogue, he goes on to suggest that with this kind of understanding:

“… ‘difference’ and disagreement are to be seen not, in a negative aspect, as impediments but rather as the liberating conditions of our conversation. ‘Conversation’ here should not be taken to mean simply pastime. Rather, conversation might be understood in a strong sense as an existential ‘turning-towards’ the other in recognition of what it means to be human.

There are, to be sure, certain universals in our humanity; and it will always be important to reveal these and allow them to speak through all our utterances. But one of these universals must be that we cannot, individually or at one single point in time, encompass the Absolute – any more than, in translation, we can exhaust the possibilities of the original text…

Each of us lives and speaks to others in an apophatic atmosphere. And to acknowledge this is not to inhibit dialogue – or to prevent our turning, in conversation, each to each. We are in via (on a journey) and our traveller’s tales can be as much a source of delight – or inspiration – as of distress. Travelling on, one notes, and talks about, the colouration of leaves along the autumn roadside or the radiance of dust-clouds on the horizon illuminated by the setting sun.”

Thinking of dialogue in these terms makes it clear that the conditions for successful communication are very much as Rowan Williams outlined them in his invitation to the event:

“… to be ready to speak and listen, hopefully, patiently, thoughtfully, and to build relationships that have the potential to help us all grow in clarity.”

And it also tells us that talking to people, and engaging in conversation with the aim of understanding, in a precise and particular way, what they are trying to convey, is an essential activity in a world where globalisation is a fact of life, and in which we are seeing a perhaps unprecedented mixing of people from different cultures and races. Just how important this is has been underlined by the Benedictine priest Lawrence Freeman in his book Beauty’s Field, where he describes his visit to Sarajevo in 2007 in the wake of the Bosnian war. Struck by the remarkable level of interfaith activity he observed between the different communities, he asked a local Muslim leader about it. And he was told: “We know only too well what happens when dialogue stops.”

Please follow and like us:

The other major theme that emerged from this day was the need for education. The need to “get our facts straight” – whether this concerns the numbers of refugees coming to Europe, the impact of our consumer choices upon the environment or our pre-existing ideas about other races – came up over and over again. And it was clear that this is the sphere where practical measures can be – or are already being – taken. One very interesting project which was mentioned from the floor in the final plenary is the recent Monmondo project which offered to analyse people’s DNA to show them the geographical range of their ancestry – thus revealing in a very direct way the myth of national identity/racial purity and the reality of the ‘human family’ (“In a way, we are all kind of cousins”).

Another project is now being developed by the Inspire Dialogue Foundation itself. Called ‘Education for Human Solidarity’ (which will also be the title of next year’s dialogue), this initiative aims to establish a set of resources on human values for teachers, based on the latest educational research. This is the first of what one suspects will be many tangible fruits to emerge from these dialogues in the future. For, as David Bohm, one of the pioneers of the this kind of conversation, said:

“Free dialogue may well be one of the most effective ways of investigating the crisis which faces society, and indeed the whole of human nature and consciousness today. Moreover, it may turn out that such a form of free exchange of ideas and information is of fundamental relevance for transforming culture and freeing it of destructive misinformation, so that creativity can be liberated.”

Inspire Dialogue, formerly Dialogue at Cambridge University, was initiated, nurtured and inspired by the vision and good heart of Bill Papworth, May 1, 1934 – August 9, 2014.

Photos by Martin Bond Photographers

Inspire Dialogue Introductions: Lord Rowan Williams

Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge

“When we go out and encounter others, we are asking for something that is not already there to come alive in us.”

Inspire Dialogue Introductions: Frederick Smets

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR)

“Most of these people do not need money, but they need somebody that they can have a conversation with.”

Inspire Dialogue Introductions: Tawanda Mutasah

Senior Director of Law and Policy for Amnesty International

“The stranger or ‘the other’ is a notion that we construct in our quest for a resource. In reality, there is no ‘other’…”

Inspire Dialogue Introductions: Baraa Halabieh

English-Arabic translator

“What makes humanity so beautiful is our multiculturalism… the variety in our colours, cultures and beliefs is what makes us all unique.”

Inspire Dialogue Summaries: The Environment

Bhaskar Vira

“How do we have a dialogue with someone who is fifty years away from inhabiting this earth? This leads to considerations of inter-generational responsibility.”

Inspire Dialogue Summaries: Conflict Resolution

Brendan Simms and Alison Liebling

“We were criticised and ridiculed by other professional groups for coming into a maximum security prison with the word ‘trust’ in mind.”

Inspire Dialogue: Final Summary

Lord Rowan Williams

“To be able to imagine that things don’t have to be as they are is perhaps one of the most important things that human beings ever do.”

Sources mentioned in the article:

Lawence Freeman, Beauty’s Field; Finding God in Unexpected Places (Canterbury Press, Norwich, p.52)

For David Bohm and colleagues on Dialogue see: http://www.ratical.org/many_worlds/K/dialogueProposal.html

MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE:

Unlocking the Heritage of Tibet

Dylan Esler talks about the ancient contemplative tradition of Dzogchen Buddhism – the ‘effortless path’ – and the 84000 Project, which is preserving the precious heritage of Tibetan Buddhism

‘Once we learn to dissolve that sense of having to react to whatever occurs, then we open up to a more spacious perspective, and that is the perspective of non-duality.’

The Vision of Esalen

Michael Murphy, co-founder of the Esalen Institute in California, reflects on the contribution of an institution that has revolutionised our understanding of spirituality

‘We’re all, whether we know it or not, together involved in a cosmic jailbreak, breaking out of our golden chains.’

Transmission Across Cultures

Writer and art historian Diana Darke brings to light the largely unacknowledged influence of Islamic architecture and craftsmen on the iconic buildings of Europe

‘If you are building a prestige project, of course you’re going to go for the best, wherever it comes from.’

George William Russell: A Forgotten Irish Mystic

Gabriel Rosenstock gives a poetic response to twelve visionary paintings by the ‘myriad-minded’ writer and polymath

‘[Through his works] we may see the world once more in its primal beauty, may recover a sense of the long-forgotten but inextinguishable grandeur of the soul’

Rolling Out the Doughnut

Leonora Grcheva of DEAL talks about how Kate Raworth’s innovative economic theory is being translated into sustainable practice in cities across the world

‘The Doughnut gives us a new way to conceptualise who we are, how we position ourselves as part of the living world, and how we can reimagine our future’

Emily Young: Giving Voice to the Earth

The distinguished sculptor Emily Young talks about her work and the stories that stone can tell us

‘What does it look like when a human is at one with the universe? Embracing it all…’

Richard Lewis: Pilgrim in the Land of Children

Robert Hirshfield appreciates the work of a teacher who has devoted his life to inspiring children to write imaginative poetry

‘A child is the privacy of a universe learning to talk to itself.’

The Power of Gold

Alan Ereira talks about his new book, which traces the relationship between human beings and this most precious metal over a period of 7,000 years

‘The notion that gold contains immutable value is somehow enormously powerful. Of course, gold doesn’t actually have that value in itself; we attribute that to it without thinking, unconsciously.’

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

The Philosophy of Prayer

Distinguished theologian George Pattison talks about the meaning of prayer in the modern world and how it brings us to awareness of our essential nothingness

‘Our starting point always has to be that we are not makers of our own being, but we are before we start doing anything for ourselves.’