Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 4, 2017

Mysticism in Comparative Perspective

Professor George Pattison talks about the revival of a unitive approach

Mysticism in Comparative Perspective

Professor George Pattison talks about the revival of a unitive approach

One of the notable movements to take place during the 20th century was the emergence of the mystical traditions of both east and west into mainstream culture. It was a period when new translations brought the great texts of all the major spiritual traditions into European languages; in English, we saw R.A. Nicholson’s translation of Jalāl al-dīn Rūmī’s Mathnawi (1925), W.B. Yeat’s Upanishads (1938), Richard Wilhelm’s I Ching (1950) and Maurice O’C. Walshe’s Meister Eckhardt (1979), to mention just some of the major landmarks. At the same time, scholars such as Evelyn Underhill within Christianity, and Margaret Smith and Anne-Marie Schimmel within Islam, brought to our attention the important and profound work of many previously little-known contemplatives within the Abrahamic traditions. Today, the writings of people such as Julian of Norwich, John of Ruusbroec, Margaret Porete, Mansur al-Hallāj, Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabī and Rābiʿa ʿAdawiyya, as well as works from Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, etc., can be read by anyone who has an interest in these matters.

One of the notable movements to take place during the 20th century was the emergence of the mystical traditions of both east and west into mainstream culture. It was a period when new translations brought the great texts of all the major spiritual traditions into European languages; in English, we saw R.A. Nicholson’s translation of Jalāl al-dīn Rūmī’s Mathnawi (1925), W.B. Yeat’s Upanishads (1938), Richard Wilhelm’s I Ching (1950) and Maurice O’C. Walshe’s Meister Eckhardt (1979), to mention just some of the major landmarks. At the same time, scholars such as Evelyn Underhill within Christianity, and Margaret Smith and Anne-Marie Schimmel within Islam, brought to our attention the important and profound work of many previously little-known contemplatives within the Abrahamic traditions. Today, the writings of people such as Julian of Norwich, John of Ruusbroec, Margaret Porete, Mansur al-Hallāj, Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabī and Rābiʿa ʿAdawiyya, as well as works from Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, etc., can be read by anyone who has an interest in these matters.

The initial study of these texts led to the perception that at the level of mystical experience and perception, there is similarity and unity between the spiritual traditions, even though the outer forms of expression may be very different. So it was understood that a Buddhist, a Hindu or a Sufi – or even someone without any formal religion – all have the ‘same’ experience of an absolute reality which in some way transcends their socio-cultural, historical and religious context. However, in the 1960s with the seminal work of Steve Katz, [1] this ‘essentialist’ view was challenged by what has become known as the ‘contextualist’ approach, which maintains that all experience is conditioned by the cultural context and expectations of the mystic. This became so influential that in recent decades comparisons between the experience of different traditions has fallen out of fashion, and even been regarded with suspicion in many academic circles.

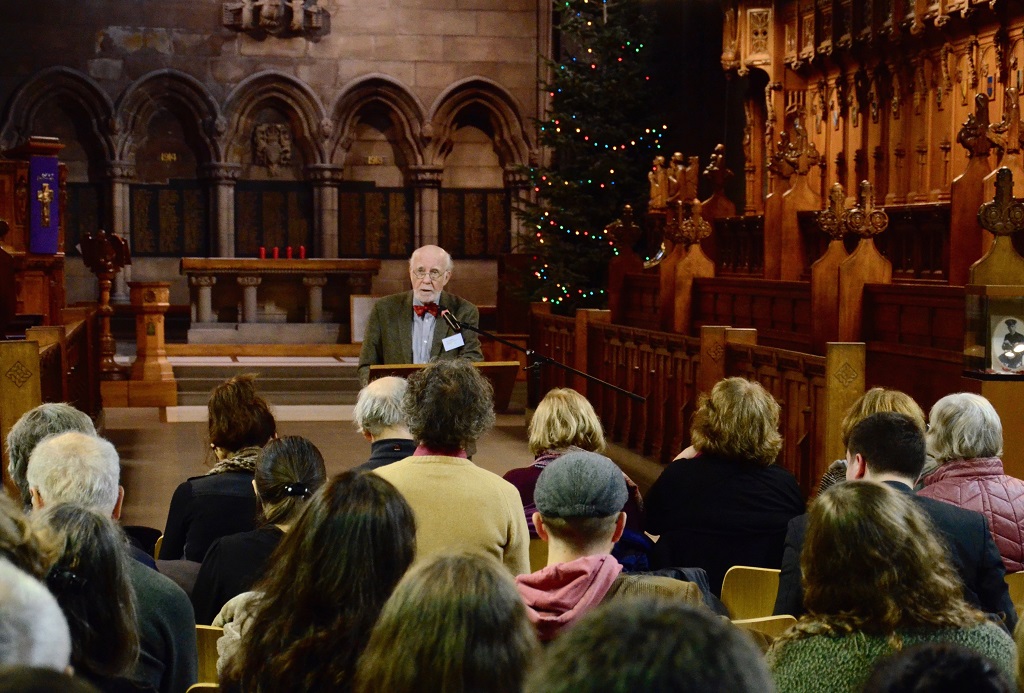

It is refreshing, therefore, to find a group of people attempting to revive a unitive approach to the mystical traditions of the world. To this end, at the end of last year from 14–16 December 2016, about 100 people from many different cultural and religious backgrounds, gathered in the august setting of Glasgow University to discuss the theme of ‘Mysticism in a Comparative Perspective’. We travelled to Glasgow to see what was going on, and to talk to one of the organisers, Professor George Pattison, 1640 Chair of Divinity at the University of Glasgow, about why he thinks that the time is ripe for a relaunch of the comparative project.

The Study of Mysticism

.

Jane: First of all, can we ask you how this conference came about?

George: The conference was jointly organised by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Glasgow University and The Mystical Theology Network [/]. The Network had its first meeting in 2012 in Oxford, when I was still Lady Margaret Professor there. It was an initiative of Louise Nelstrop, then at Oxford but also now teaching here in Glasgow. She thought it would be nice to bring together a group of people who had a shared interest in mysticism, imagining that it would consist of a dozen or so participants. But about 80 people turned up, and it has developed really from there. This is the sixth conference we have held, and the first in Glasgow.

Elizabeth: There were nearly 50 papers delivered over the three days of the conference, covering a very wide range of subjects. This would seem to indicate that, despite the ‘official’ attitude towards the study of these matters, a great deal of work has been going on.

George: I think that it is perhaps in the nature of academic disciplines for people to be suspicious of appeals to experience – to what can’t be said, to things of the heart. Academics want to see facts and arguments, something you can deal with in language, and in which you can make historical comparisons and so on. So there has been a certain amount of resistance to taking on mysticism as an academic subject. But I think that has begun to change now, not least because so many people are interested in the subject.

Also, mysticism has clearly been a major cultural force. One of our keynote speakers this year, Bernard McGinn from the University of Chicago, is in the process of writing a comprehensive history of Christian mysticism, starting from the earliest centuries CE. [2] His work has been very important in making the study of mysticism respectable again, because he has presented the material alongside a strong historical argument that shows that you cannot really think about Christian history without looking at the influence of the mystical tradition.

Jane: The first six conferences of The Mystical Theology Network basically stayed within the realm of the Christian tradition. But this year you have made a decision to include other traditions and to tackle head-on the current academic backlash against ‘comparativism’.

George: There are of course many people in this field who think that comparing the different traditions is a fraught project. They maintain that there is no such thing as ‘religion’ in a general sense; that it is just a construct reflecting Western, specifically Christian, colonialist attitudes. This is because when western Christian colonialists went to India or Africa or America and encountered certain phenomena, they interpreted them as religions when they were nothing of the sort. So this point of view regards the things we call ‘religions’ as being all quite disparate.

I think that there is a grain of truth in this. But my own view is that one can overdo its importance. When you look at the Christian, Jewish and Islamic traditions, it is quite clear that they have a great deal in common in terms of their sources – not only their biblical sources, but also the heritage of Greek philosophy, Plato and Aristotle, the Stoics, etc. These are common influences that are reflected in each of the traditions.

And I think that the same holds if one looks further afield; some philosophers would say that many of our metaphysical assumptions are actually hard-wired into the structure of our language. So for those of us who speak Indo-European languages there are commonalities of structure that would extend to the religions of India, for instance.

Jane: But I can see that there might be problems in extending that argument to other languages, such as Chinese – or even to Arabic, which has a very different linguistic structure. One of the conversations I had during the conference was with a Japanese scholar who is a specialist in Islamic thought, but is now starting to look at the forms of her native spirituality. She feels that the very notion of ‘mysticism’ may itself be a Western construct because in Zen and Taoism, they don’t have the same distinction between the esoteric and exoteric tradition that we have within Christianity or Islam.

George: Well, I would have to defer to someone who knows more about the far eastern traditions than me. But from the texts that I know from Zen literature in China and Japan, it is clear to me that they do have concerns about the nature of reality; about some kind of immediate experience of living reality; about learning to disentangle ourselves from the habits of everyday perceptions, and from everyday assumptions about knowledge. There are obviously differences with the western traditions, but those differences don’t exclude common concerns.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that in the modern world many of the interpreters of Zen Buddhism, for example, have themselves been influenced by Western modes of expression. Someone like D.T. Suzuki, [3] who was one of the most influential interpreters of Zen in the 20th century, had studied Western philosophy and used it in his exposition. Of course, some Japanese would say – and do say – that he westernised it in inappropriate ways. But nevertheless, when Suzuki and other philosophers, such as Keiji Nishitani who studied with Heidegger,[4] think they can use Western philosophy to help interpret Zen, we shouldn’t just brush them aside. They are coming out of that tradition, and they are saying, yes we can use this to help interpret it, and so we should listen to that.

Jane: The argument would not be that the concerns aren’t the same but that they are mainstream. They are totally part of the actual religion whereas many people within the Christian tradition – or indeed, within the Islamic tradition these days – regard these ideas as obscure and even dangerously heretical.

George: I think that’s partly true. But when you go to a Buddhist country, you find that most Buddhists don’t spend all their time sitting around meditating. Most of them go to work nine to five, and they go to the local temple now and again and make offerings to the Buddha or one of the various Bodhisatvas or deity-like beings who are part of their mythology. In many ways, they behave more like the majority of Western Christians than they do like Buddhist monks, who are in fact a very small minority within Buddhist culture.

Elizabeth: There is the famous saying: “Before enlightenment chopping wood and carrying water; after enlightenment chopping wood and carrying water”. I think one of the problems is that for many people the term ‘mysticism’ implies people sitting in meditation all day, or going into a trance, or in some way removing themselves away from the world: that it is something ‘other-worldly’.

George: Yes. In fact, one finds in both the Eastern and the Western mystical traditions – with someone like Meister Eckhart, for instance – criticisms of people who either develop a too-theoretical approach to religion, or else are too busily engaged with religious rituals and practices. Within the Christian tradition, we have the example of Brother Lawrence who found God amongst the pots and pans in the kitchen where he worked. Mysticism is not necessarily something terribly weird or wonderful: it consists of a certain kind of attention to reality in all its facets – which of course includes washing up, catching buses, and all the everyday things that we do.

Elizabeth: People tend to think that it is all to do with a transcendent reality. Whereas for the great mystics, the ultimate achievement is to see the transcendent in the immanent and vice versa.

George: I think it’s like a lot of general words. The kind of mysticism that I like is that which happens amongst the pots and pans. But clearly there have been other forms where people do cultivate what they regard as superior mental states. It seems to me that a good comparison is with the word ‘art’, which in a sense is also a word invented in modern times. People like Fra Angelico or Giotto didn’t think that what they were doing was ‘art’. They regarded themselves simply as artisans, workers, craftsmen, who were doing a job that they were paid to do – an important job that they would do with reverence, but they were not regarded as artists or artistic geniuses in the way we understand those things today. Nevertheless, the category of ‘art’ is useful to interpret what they were doing. None of us now would go into Santa Croce in Florence and say, ‘Oh, that’s not art!’. It is art of the highest quality, even perfection. So the category is useful even though it does not necessarily express the way that the artists themselves thought at the time.

And again, as with mysticism, art covers many different things. There’s Fra Angelico and there’s Jackson Pollock, and there are many weirder artists than Jackson Pollock, who has become quite classic and conservative by now. Nevertheless, it makes some kind of sense to think of all these things as art, and if we say of someone that they’re very interested in art, we know that that means something different from saying that they’re interested in fishing. So these are to some extent rough-and-ready terms which are useful, but only as long as we don’t push them too far.

The Comparative Approach

.

Jane: One of the things that came up very strongly in the conference was the benefit of the comparative approach. Bernard McGinn went so far as to suggest that everybody should become familiar nowadays with at least one other tradition apart from their own. We also had a counter-argument to this, brought by Victoria Harrison of the University of Macau. She drew on the idea that the knowledge with which the mystical traditions are concerned is universal truth, and that it is the heart, or essence, of religion – of all religions. She brought an analogy: that this knowledge is like the pure gold that lies at the bottom of every gold mine. So why can we not just go down into our own mine to find it? Why should we need to go down any other mine?

George: There are clearly some people who live their own religion to such a depth that what they discover is a universal truth. They are able to work past the dogma and the institutions within the tradition, and find the gold, the heart, the humanity, in it. But I think that it is also part of contemporary reality that we are living in a globalised world where, at all levels, cultural interaction is part of what we are. You can see this in music, you see it in art, in food, and so why not in religion?

We constantly come across different traditions during the course of our lives. I myself was intrigued by Buddhism at an early stage of my life, and practiced it a little, largely influenced by hearing a Tibetan Lama giving a talk in one of the colleges at Cambridge. And when I was 16, my parish priest, Brian Dupré, took me to my first-ever theological lecture, which was by Raimon Panikkar. [5] He was a Jesuit priest, half Indian, half Spanish, who was theologically interested in dialogue between Christianity and the Hindu tradition. This was at the time when he was writing the book The Unknown Christ of Hinduism in which he argues that Hinduism already has the mystery of Christ within it. For me this was a seminal influence on everything that has happened since.

There was another theologian I read in the early ’70s called John S. Dunne – a Catholic priest and Professor of Notre Dame University, who died in 2013. [6] He talked about what he called ‘passing over’, meaning, passing over from one religion into another, and then passing back into one’s own. This seems to be part of the natural process of human growth and discovery. Of course, we make all sorts of mistakes and there are all manner of confusions: the things which attract us westerners in other religions are perhaps the exotic things – the different costumes, the different clothes – that maybe people within those traditions would actually like to get rid of.

Jane: There is an interesting story in the Persian poem ‘Conference of the Birds’ [7] which illustrates precisely this idea of ‘passing over’. It is about a great spiritual master and ascetic, Shaykh Samʾan, who, when he is an old man, suddenly falls in love with a young Christian girl. He is so besotted that he leaves everything to follow her, and even renounces his faith – to the great distress of his disciples. But in the end, he has a dream which returns him to Islam, and it all ends up in a great reconciliation.

George: There is another famous Jewish story which was told by the great scholar of religions, Mircea Eliade, which goes like this: there was a poor Jew in one of the shtetls in Eastern Europe who had a dream that there was a treasure – a hidden treasure – in a nearby city. When he woke up, he thought that he would go and find this treasure, so he journeyed for four days, which was a big deal because he was very poor. When he got there he asked the guard to tell him where this place was. The guard laughed, and said; “Oh how stupid you Jews are; fancy coming all this way to look for a treasure here. I had a dream the other night about a village in which there is a Jewish shtetl under which there is a treasure buried…” and he described this man’s house; “… but I am not stupid like the Jews. I am not setting off to find it.” So of course, the Jew went back to his house and dug up the treasure. We go off looking for something when it is with us all the time. But sometimes, you have to go away to find it.

We also have to remember that there is no religion which is completely original. All of them have emerged in an evolutionary historical process, and even the most ancient human religions developed at a certain point in history, although the knowledge of their origins may now be lost. So we are all in some ways relative to one another. We have arisen at different points, but there is no absolute religion; we are all, and have been all the time, on the way. Images of pilgrimage or wandering are part of the vocabulary of all religious traditions, especially the mystical traditions: setting off, wandering who knows where, leaving behind what you knew before, and not knowing what you are going towards.

Mysticism in the World Today

.

Elizabeth: In your opening talk, you said that you thought that this ‘comparative perspective’ is very important in the world today. Why do you think this is so?

George: One of the features of the world today is a perceived conflict between religions, and all in the name of religion. There is a great deal of violence carried out in the name of religion, which is one of the things leading many people to reject all possible forms of faith because they see that it is inherently violent and dividing people from each other. I think that kind of reaction is often as ignorant as the position that it is attacking, because if we go back in history, we can see that there were times, such as in 10th-century Baghdad, when Christian, Muslim and Jewish theologians debated together under the protection of the rulers. These things have happened in many parts of the world at many times. So there is nothing in religion which is intrinsically more divisive than in any other cultural phenomena. But this is the perception of our time, and people use religion as a means of creating divisions. So it is all the more important to work against that.

It is great, therefore, that at this conference we had people who were practicing Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist and Hindu faiths, and other forms of religion as well. Unfortunately, about half-a-dozen people from Turkey, Iran and Pakistan had difficulty in getting visas and could not attend. This is another fact of our world – that it is divided up into countries which regard each other with suspicion. I think we should all look forward to the day when there are no national boundaries of that kind, and we can wander freely on the face of the earth. That is a long way off, and is a kind of utopian vision: but if we do believe in common humanity, we shouldn’t be imposing these boundaries.

Jane: I think it would be wonderful to think that we could get to the point where we could do this. Before we finish, could we ask you about the module on mysticism and spirituality which you run as part of your undergraduate course at Glasgow? This seems to me to be a real indication of the rehabilitation of mysticism into the cultural mainstream. Is this the only place in the country where you can do such a course?

George: No. There is actually a course in Oxford which I helped to set up, though I left in 2013 before they started to teach it. But when I came here, I found there was already a mysticism and spirituality course up and running. The curriculum varies a little bit from year to year according to who is available to teach it, but it usually involves input from colleagues specialising in Christianity, in Buddhism, in Islam, and in Judaism. We don’t currently have anyone that can really do Hinduism, so Hinduism is not included at the moment. But that is not for any ideological reason: we just don’t have someone to do it.

Jane: Is the course fully integrated into the student’s academic career? I ask this because in many universities now, students can take a module on a subject such as this but only as an extra, non-assessed subject.

George: This is a fully-accredited module. Although it’s a second year course, which under the Scottish system means that it is not part of a student’s honour’s degree specialisation. We get up to about 80 students taking the course each year, of which maybe half will be specialising in theology or religious studies and the rest will be engineers, geographers, linguists, etc. Interestingly, quite a lot of our Erasmus students (i.e. students from European universities studying at Edinburgh) tend to take it and they usually do very well.

Elizabeth: One of the questions that arises with the academic study of something like religious experience is whether or not it can really be done objectively, without being personally committed?

George: I think that one can make an analogy here with the natural sciences. A chemist should not be heavily invested in the financial outcome of their experiment before they do it. The point is to conduct the experiment and if the result is one that they don’t like, then tough luck; they have to acknowledge it and work with it. The same is true to an extent within the humanities. Sometimes we come up with things that we don’t like, so that we wish that certain things weren’t the case, or had not happened as they did. I myself work on the German philosopher Heidegger, who I think was one of the most important thinkers of modern times. His work opens up very interesting possibilities for dialogue between Western thought and Buddhism, and he had many Japanese students, and also Iranian. At the same time, he became a Nazi, and his work is deeply problematic politically, and I have to face up to that.

Nevertheless, I think within the humanities, there is always a proper place for personal interest in the subject. In fact, I think that most people working within humanities – whether on poetry or history or religion – do have some sort of personal investment in their subject, and that sets up a tension. Because, as I have said, we cannot approach a subject wanting a particular outcome, or wishing to impose our own point of view on it.

Moving Forward

.

Elizabeth: So given the title of the conference – ‘Mysticism in a Comparative Perspective’ – what do you feel came out of it in terms of the implicit question it posed? How do you see the way forward in this matter?

George: In concrete terms, I’m hoping that we will get at least one book out of the conference proceedings, although with the way these things work this won’t appear for another couple of years. More broadly, I hope that it will have contributed to broadening and strengthening the ‘network’ aspect of The Mystical Theology Network, and communication between people working in and on mysticism in both practical and theoretical ways. Human beings have important needs for solitude, but they are also sociable and collaborative creatures, and things often only come to the surface when you really start talking about them in earnest. Progress is only ever going to be incremental, and it often seems that we have to run in order to stand still, both in scholarship and religious practice.

Contemporary politics suggests that appeals to pursue excessive wealth, or to indulge in aggressive and sometimes lethal posturing, remain as attractive as ever, which is deeply saddening. But even if that is a misreading of the current climate (and there are, of course, many other tendencies as well), even choosing to focus in academic ways on practices directed towards compassion, peace and mutual understanding has to be doing some good – though, fairly obviously, not as much as actually practicing them in our own lives. “Go and do likewise!” as Jesus once said.

George Pattison is a theologian and an Anglican priest, with particular interests in philosophy – notably Kierkegaard, Heidegger and Dostoyevsky – and the theology of art and film. He has held the 1640 Chair of Divinity at the University of Glasgow since 2013. Before this, he was the Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity at University of Oxford (2004–13) and a Canon of Christ Church Cathedral. His many publications include:

Art, Modernity and Faith (Norwich, SCM Press, 1998; revised edn)

Thinking about God in an Age of Technology (Oxford University Press, USA, 2007)

God and Being (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011)

Kierkegaard and the Theology of the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, CUP, 2012)

Image Sources (click to close)

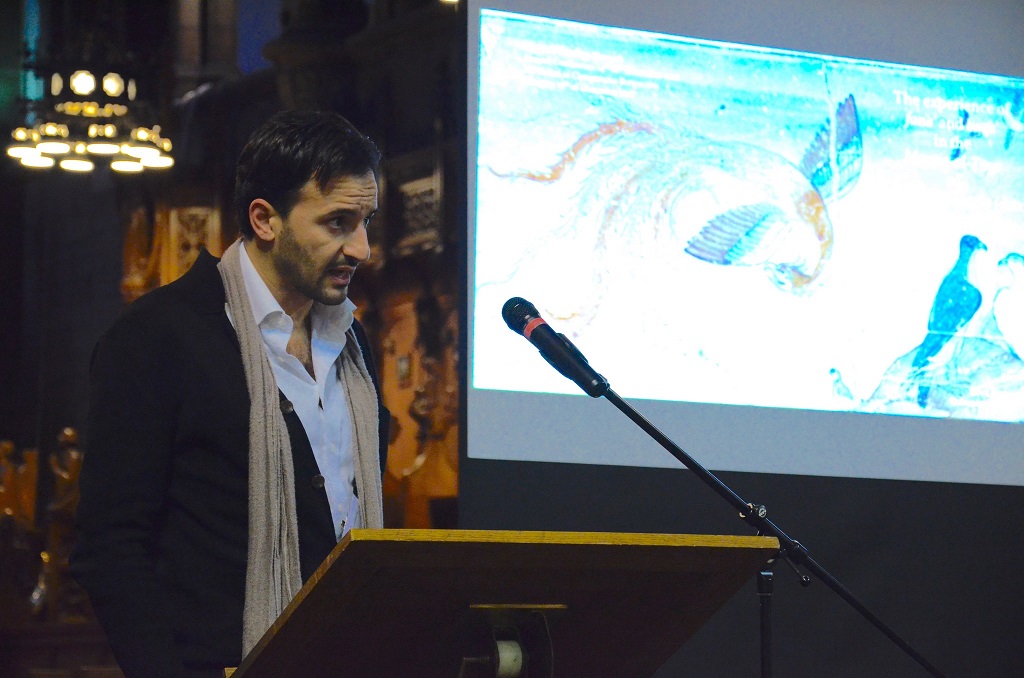

All photographs by Pol Hermann.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] KATZ, STEVEN T.: “Language, Epistemology and Mysticism” in Steven T. Katz, ed., Mysticism and Philosophical Analysis (Oxford University Press, 1978), pp. 22–74. http://www2.trincoll.edu/~kiener/KatzS_Language_Epistemology_Mysticism_1978.pdf

[2] BERNARD McGINN: “The Presence of God” Series (Crossroad, New York)

The foundations of mysticism (1991)

The growth of mysticism (1994)

The flowering of mysticism: men and women in the new mysticism (1200–1350) (1998)

The harvest of mysticism in medieval Germany (1300–1500) (2005)

The varieties of vernacular mysticism (1350–1550) (2013)

Mysticism in the Reformation (1500–1650) (2017)

[3] D.T. SUZUKI:

Essays in Zen Buddhism (Grove Press, New York, 1927, 1933, 1934)

The Zen Doctrine of No-Mind (Rider & Company, London, 1949)

[4] KEIJI NISHITANI: Religion and Nothingness, trans. Jan van Bragt (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1949)

[5] RAIMON PANIKKAR:

The Unknown Christ of Hinduism (New York, Orbis Books, 1964; subsequent edn 1981)

The Silence of God: The Answer of the Buddha (New York, Orbis Books, revised edn 1989)

See also: “Making a Bridge to the Unknown” in Beshara Magazine, Issue 10, Winter 1989

[6] JOHN S. DUNNE: The Way of All the Earth; experiments in Truth and Religion (Indiana, University of Notre Dame Press, 1986).

[7] FARID AD-DIN ATTAR: Conference of the Birds, trans. Afkham Darbandi and Dick Davies (London, Penguin, 1984)

For more information about The Mystical Theology Network, click here [/].

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments