Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 13, 2019

The Wisdom of Time and Transformation

Dr Alison Roberts explains the ancient alchemical knowledge of Egypt

The Wisdom of Time and Transformation

Dr Alison Roberts explains the ancient alchemical knowledge of Egypt

Dr Alison Roberts has spent a lifetime studying the sacred traditions of Egypt, drawing out in particular the importance of the feminine and the principles of transformation. Her fourth book, Hathor’s Alchemy, published this year, focuses on the great goddess, Hathor, and the temples dedicated to her at Abu Simbel and Dendara. Subtitled The Ancient Egyptian Roots of the Hermetic Art, it also traces the way in which this ancient wisdom found its way into the mystical and alchemical traditions of Greece, Islam and medieval Europe. Here she talks to David Hornsby about the relevance of these ideas to our modern lives.

David: What struck me when reading your book Hathor’s Alchemy [1] is that it reveals the ancient Egyptians as having a completely integrated way of life. All through the day and all through the night, there was awareness of the progression of time, and they had a very human response to it. It is a refreshing perspective as, so often when we talk about Egyptian civilisation, it is all about the buildings – the beautiful temples, their extraordinary size, the building techniques used, etc. – but your book explains what their culture was actually about.

David: What struck me when reading your book Hathor’s Alchemy [1] is that it reveals the ancient Egyptians as having a completely integrated way of life. All through the day and all through the night, there was awareness of the progression of time, and they had a very human response to it. It is a refreshing perspective as, so often when we talk about Egyptian civilisation, it is all about the buildings – the beautiful temples, their extraordinary size, the building techniques used, etc. – but your book explains what their culture was actually about.

Alison: You can’t help but be aware of time when you are in Egypt; it is just the whole landscape that you’re living in. As you say, the ancient Egyptians were deeply immersed in every hour of the day, and the changing qualities of light were seen as the journey of the gods Re and Hathor across the sky from dawn to dusk.

David: You originally studied Egyptology at the University of Oxford. How did you arrive at the unitive approach that you have developed in your books?

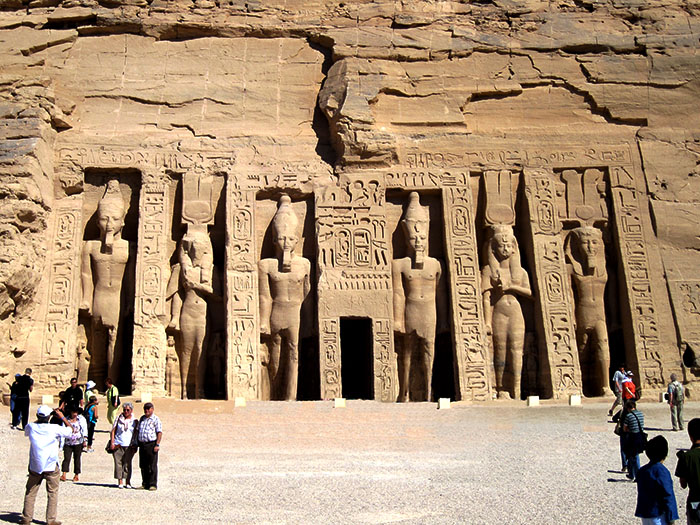

Alison: It is true that Oxford is a much more humanist, classically oriented, world, which is not really the approach that I’ve taken in Hathor’s Alchemy. I first encountered Hathor in 1974 when I was an undergraduate there, studying both Egyptian and Akkadian. I made my first trip to Egypt with a group, visiting Cairo first of all, and then flying to Aswan, and finally to Abu Simbel. I knew very little about the civilisation at that time, but I was just amazed by the place. At Abu Simbel, we first went to the Great Temple, dedicated to Ramesses II, which had been moved only about six years before.

David: This was because of the Aswan Dam … when they flooded the valley and moved the temples to higher ground?

Alison: Yes, that happened in 1969. I found the large temple very impressive, but then we made our way to the small temple, the one dedicated to Ramesses’ queen, Nefertari, and to Hathor, whom I knew nothing about. But as soon as I entered, I just felt peace and beauty. It was like nowhere else I’d been. We didn’t spend long there because everybody else wanted to get back to the Great Temple, but I suddenly felt impelled to return. The guard was just locking the door, but I asked him if I could sit for a while. And he said yes. So I sat on the step leading into the middle chamber, looking out, and he was perched in the doorway with his Ankh-sign of life, his key on his knee, and Lake Nasser glittering beyond. And I just felt a presence that I had never experienced before.

Then, at the end of my Oxford course, I went to Copenhagen to study Sumerian with Dr Bendt Alster. Sumerian had been my first interest but I had not been able to find a suitable undergraduate course, so this was a chance to pursue it. But as soon as I got there, I met the Egyptology Professor, John Harris, who was English. He urged me not to give up on my ancient Egyptian, and offered to support me in writing an article during my year there. He helped me develop my symbolic approach, and that’s when I began to work on Hathor.

David: It sounds as if this book has taken you forty years to write?

Alison: Yes, you could say that. Although I did not know at the time that I would have to engage with alchemy as well!

View of Hathor’s temple at Abu Simbel, showing huge statues of Ramesses II and Queen Nefertari carved in the recesses. Photograph: Olaf Tauch via Wikimedia Commons

The Meaning of Hathor

.

David: There are more temples dedicated to Hathor than to any other Egyptian goddess, so she was an extremely important figure. What is her role in traditional Egyptology?

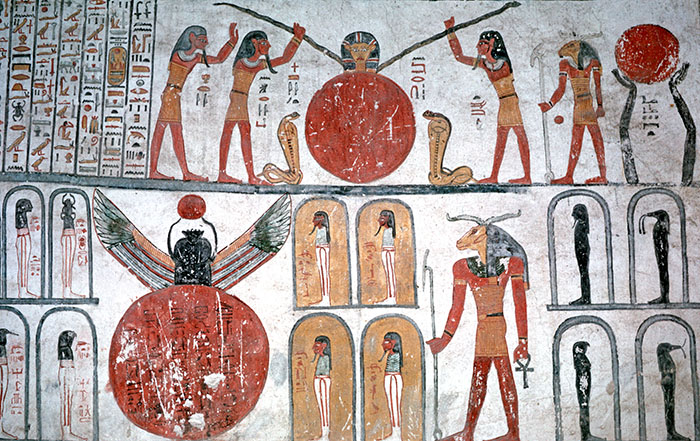

Alison: Well, she’s sort of the Egyptian Aphrodite, the Egyptian Venus. She’s the goddess of music, of love. But she’s much more than that. She is really the Sophia of Egypt: the goddess of wisdom, the initiating goddess. She is a metallurgical goddess too, ruling the mining districts where the Egyptians obtained copper and gold. This is why she is associated with alchemy, copper and gold being at the heart of the Egyptian alchemical tradition.

In myth, she is the partner, the female counterpart, of the Sun God, Re, and their movement through the heavens defines the passage of time through a day. The transformations that they experience on the way are seen as symbolic of the larger cycle of human life – that is, the changes we may experience in a lifetime – and even larger than that, the cycle of cosmic birth and return.

David: Can you say a bit more about this daily cycle, which of course we all live within?

Alison: The rhythm of sleeping and waking is integral to each one of us. Modern biologists are discovering that it is fundamental to all life on Earth, and this is what the Egyptians knew and celebrated thousands of years ago. It is a psychological rhythm: a rhythm of unfolding going on day after day after day. If we become attuned to it, we can live in awareness of this – waking in the morning, growing and maturing, and then sleeping, entering the realm of sleep, and the night realm of regeneration. But it’s also a relationship with the natural world around us, with the transformative rhythms of the annual cycle of the cosmos, the sun and the moon, the stars.

David: What is Hathor’s role in this?

Alison: Biologists now know that this rhythm of waking and sleeping is ruled by the eye and light. Those are the principles that govern this life of ours. The Egyptians perceived it symbolically; they saw Hathor, who is the Sun Eye, as revitalising the whole cycle, moving her partner, the Sun God, Re, through the complete cycle from dawn to dusk. Her love transforms, empowers everything in this Egyptian cosmos. Rumi says something similar in the Masnavi, for instance, when he sings about

the waves of love that make the heavens turn

without that love the universe would freeze… [2]

It is the same in the Egyptian cycle. In the first hour of the day Hathor gives birth to the Sun God. Actually he’s still an embryological child, because this whole passage, this whole wisdom, is a very embryological way of development. He represents an emerging cosmos, emerging life.

David: Since Hathor is completely integral to this cycle, why do we hear so little about her? We seem to know more about figures like Horus or Isis.

Alison: Horus is her consort, as well as Re. But I think the main reason that we know so little about Hathor is because of the classical tradition. Plutarch focused very much on the Osirian mysteries, on Osiris, Isis and Horus. The Egyptian solar cycle was transmitted into Hermetic alchemy but it was not really influential upon the classical tradition – and that’s where a lot of the knowledge about Egypt has previously come from.

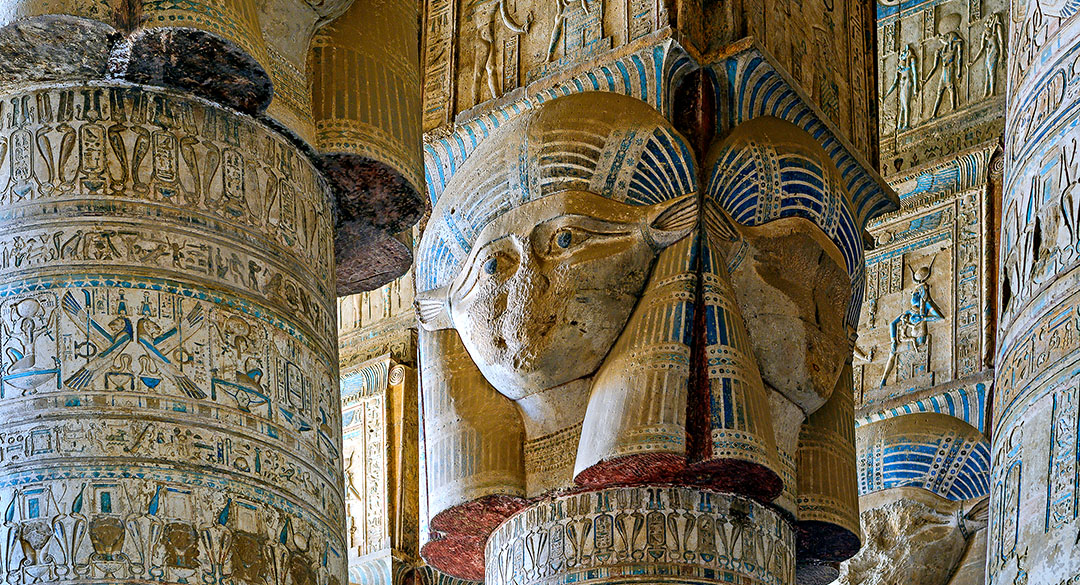

But another reason, I’m afraid, is the repression of the feminine principle, and hostility to certain types of women in late antiquity and the medieval world. In the Dendara Temple, which is one of the best preserved of the many dedicated to Hathor, you can see that her facial features have been carefully erased from the huge columns, evidently to nullify her power, erase her memory. Her name gets lost in later sources, but not her function. Islamic alchemists know her as Venus, although in an Arabic revelation of Hermes of Dendara, the temple goddess with her four faces is called Artemis. Anything but Hathor!

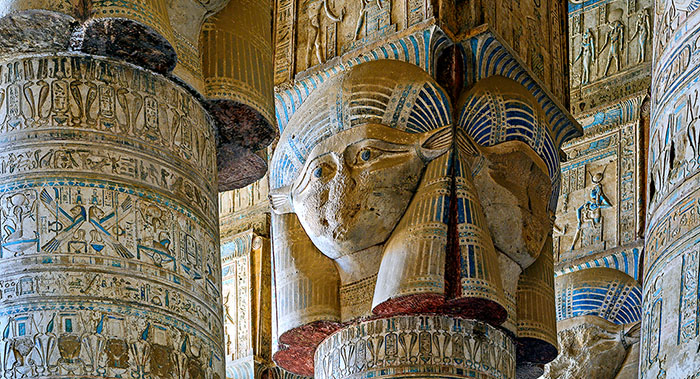

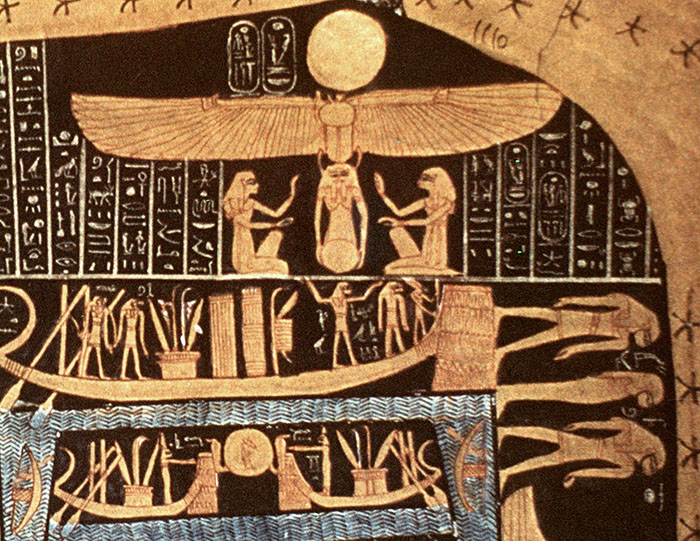

Tomb of Ramesses VI, Thebes: Hathor encloses the Sun God Re in her womb as they float in the primordial ocean called Nun in the Book of Day’s first hour. Above them soars the winged scarab Khepri (‘Becoming’), symbolic of the emerging solar cosmos in eternal movement, sustained by Hathor’s love. Photograph: AMR Picture Library

The Cycle of the Day

.

David: In your book you describe the daily cycle in detail as it is charted in the Book of Day in Ramesses VI’s tomb at Thebes. You say that it provides “a ‘celestial geography’ mapping in great detail the mythic territory traversed by Re and his companions in the ‘sun boat’”. Can you summarise the progression?

Alison: Yes. The Book of Day describes how things begin in the first hour before sunrise, hence, in the West it’s known as the ‘Rising Dawn’ tradition. The Eye Goddess Hathor is rising with the Sun God Re in her womb. This first hour is when light is just beginning to come, when life is beginning to awaken on Earth. It is the transition from the darkness when everything is waiting to come into being, and it is a wonderful time of praise for emerging beauty. In fact, the first hour is called ‘She who raises the Beauty of Re’. It’s also the hour when truth, in the form of the Truth Goddess, Maat, comes as the guiding power in the journey.

Then, in the second and third hours, it’s the emerging face of the Sun God which is being created. You have the left eye, the Moon Eye, coming into being in the second hour, and all the struggles which are involved in that. In the third hour you have the right eye, the Sun Eye. Then in the fourth hour comes the sunrise, that moment when the sun comes over the horizon and is finally seen. These first four hours are the time of the emerging creation.

David: Which is followed by the ascent to the zenith?

Alison: Yes, and that’s always a difficult time because it’s the movement to maturity. This journey is the growth and transformation of life. In those first four hours, the Sun God is changing from childhood to the youthful phase, and then trying to grow to maturity at the zenith. Now come the difficulties, because that passage from the fifth to the eighth hours is when you’re tested by the noon-day demon, and you can be drawn away from the river of life. Something might entice you away from the path. Rumi also talks about this struggle to become a mature human being: how do we grow and reach our full potential?

David: What age range is this in the human biological equivalent?

Alison: It is youth to adult, but you could also see it as the midlife crisis. It’s the passage to becoming mature, and it doesn’t always happen. The Egyptians called the tester the Apophis snake, which seeks to draw the sun boat onto his dreaded sandbank where everything becomes dry. This means that you lose that greenness, that love. But if the zenith is reached, then there is a wonderful ‘praise of the union’ between the Sun God and the Truth Goddess, which occurs in the seventh hour of the day.

Re appears, the Powerful One of Heaven,

All-armed, arising from the primordial ocean (Nun)

Lord of Manifestations within the shrine,

Driving away darkness;

Who sits on the lap of Maat,

Beloved of the heavenly Goddess in the midst of Lightland…

That is the first union. And I should mention that the energy roused to reach the zenith is the Hathorian serpent energy.

Then in the eighth hour of the day, the moon forces stabilise the sun’s course across the mid-heaven, leading to rebirth in the ninth hour of the day. To reach that peaceful ninth hour, is to reach what the Egyptians call the ‘Field of Reeds’. This is not really a physical terrain: it’s where the rebirth into divinity manifests, the rebirth of Re from the egg, where the justified ones sail with him in the sun boat.

You have to be true of heart to reach this peaceful place where everything is circulating freely. Time is flowing now in a circle like the Ouroboros snake; it is eternal time, no longer linear time. Everything is unified. And that is the second crowning in the journey.

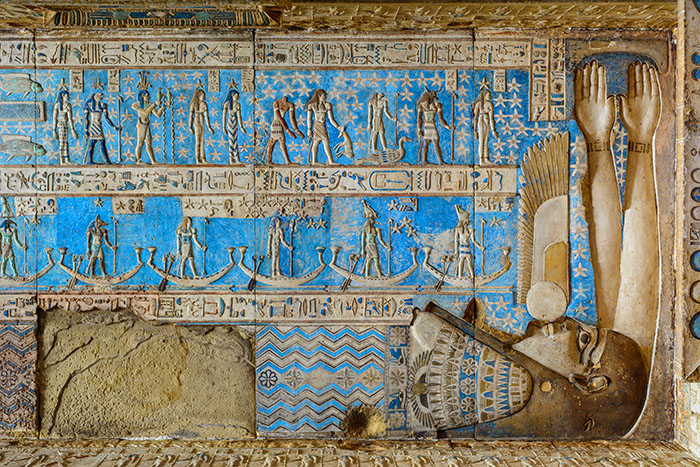

David: What time of day have we reached?

Alison: Between two and three o’clock. This is the time of nourishment. Traditionally it’s when food is taken, so it’s when nourishment is at the centre of your whole being and you are nourished by life itself in this eternal cycle. And then comes the time of ‘making the red’ between the tenth and the twelfth hours, when everything radiates in the redness created by the Sun God’s fiery serpent-uraeus [/], another aspect of Hathor. Dawn belongs to the youthful phase, to ‘whiteness’, ‘copper’ and the emerging face of Re, to harmonising the unstable passions of the Sun and Moon Eyes, bringing everything into balance. Now in the tenth hour of redness, the mature Sun God manifests his all-powerful divinity, his transmutation into shining ‘gold’, rendered visible by his uraeus-encircled, divine face. Then in the final two hours is the journey into ‘silence’ and the complete unification of heaven and earth.

Alison: Between two and three o’clock. This is the time of nourishment. Traditionally it’s when food is taken, so it’s when nourishment is at the centre of your whole being and you are nourished by life itself in this eternal cycle. And then comes the time of ‘making the red’ between the tenth and the twelfth hours, when everything radiates in the redness created by the Sun God’s fiery serpent-uraeus [/], another aspect of Hathor. Dawn belongs to the youthful phase, to ‘whiteness’, ‘copper’ and the emerging face of Re, to harmonising the unstable passions of the Sun and Moon Eyes, bringing everything into balance. Now in the tenth hour of redness, the mature Sun God manifests his all-powerful divinity, his transmutation into shining ‘gold’, rendered visible by his uraeus-encircled, divine face. Then in the final two hours is the journey into ‘silence’ and the complete unification of heaven and earth.

David: And then the night?

Alison: Yes, the night. The journey through the twelve hours of the Book of Night is a time of death and renewal, as in the Sufi message: die and be regenerated. I have described this journey in detail in my book My Heart My Mother: Death and Rebirth in Ancient Egypt. [3]

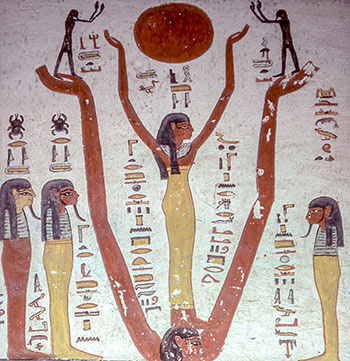

Detail from a zodiac in Hathor’s temple at Dendara, showing the sky goddess Nut floating in the eternal waters of Nun, about to swallow the sun at the ‘reddening’ time of sunset and regeneration. Photograph © Sam Gladstone

Unity and Monotheism in Egyptian Culture

.

David: Was Egyptian civilisation founded on the recognition of this cycle and its correlation to human evolution? Is this the basic principle behind all the ruins and remnants that we now see?

Alison: It was an emerging understanding with the Egyptians. It isn’t really there so much in the Old Kingdom pyramid age, which we would date at about 2686–2181 BCE. What I write about in Hathor’s Alchemy is very much to do with the union of the human and the divine; the Sun God as both human and divine, and this only really enters into the Egyptian tradition around 2000 BCE. The tomb of Ramesses VI probably dates from the mid- to late-twelfth century BCE, and Hathor’s Temple at Abu Simbel about 1265 BCE.

David: In the monotheistic traditions, Egypt, or Egyptian rulership, is often seen as being ‘the enemy’. For instance, in the Biblical and Quranic accounts of Moses leading the Jewish people out of their Egyptian captivity, Pharaoh is portrayed as an evil tyrant. Symbolically, within the mystical traditions, he stands for the ego – that part of ourselves which falsely claims divinity for itself.

Alison: Yes, this happens even in the work of Rumi, whose poetry I love. There is this polarization within the traditions of Islam, Judaism or Christianity, of monotheism versus the seemingly ‘other’ represented by Egypt. But I don’t really find that to be a helpful perspective, as it proposes a dichotomy which to me doesn’t ring true. This is because, as I show in my book, the powerful spirituality of the Egyptians has been carried through into these other traditions, deeply influencing first the Greeks and later the mystical traditions of Christianity and Islam. Hazrat Inayat Khan [/], who brought the Sufi tradition of India to the West during the 1920’s, talked very clearly about this. He always maintained that the origins of Sufism were in Egypt. Rumi uses the opposition of Moses/Pharaoh in his poetry, and yet to me the Masnavi is clearly rooted in this spirituality of the Hours, because of its sense of continuous transformation.

David: Is it not true that the Pharaoh was seen as a divinity?

Alison: This is a big point of misunderstanding. The Pharaoh wasn’t claiming divinity for himself. He was claiming it as the embodiment of the Sun God Re on earth, and he was claiming it for his people. To be the Pharaoh must have been incredibly isolating in many respects, and some of the initiation ceremonies that he went through were extraordinarily lonely experiences.

David: For example?

Alison: His initiation in the New Year ritual extended over 14 days, during which he was anointed with the oils of the Eye Goddess, Hathor-Sekhmet. Then he made a trance-like descent into the tomb of his Osirian predecessor to exchange the seals of rulership guided by priests. It was an empowerment of him every New Year, sealing his rulership. Someone going through a ceremony like that is not claiming the knowledge for himself. He is the guardian of the mysteries for his people.

But you know, even within the Egyptian tradition, monotheism was an issue. It was discussed around 1350 BCE in the reign of Akhenaten, who closed the temples and just honoured the sole deity, Re, the Sun. What, in the end, do we really mean by monotheism? The Egyptians saw deity as a unity, and the cycle of the day as the coming into being from an essence that is in continual transformation. It is a picture of complete unity.

Detail from the Book of the Earth in Ramesses VI’s tomb depicting Hathor as Copper Goddess. Her unmistakeable face appears above her fiery womb-crucible as two deities seize her snake-like arms. Beneath is Khepri as a black scarab, bursting forth from a red sun disk. The hidden is made manifest as Khepri reveals his renewed power of movement, eternally created by the Copper Goddess above. Photograph: AMR Picture Library

Alchemy and the Hermetic Tradition

.

David: In the second part of your book, you show that the principal way in which the Egyptian solar wisdom was transmitted to later cultures was through the alchemical tradition. How would you define alchemy?

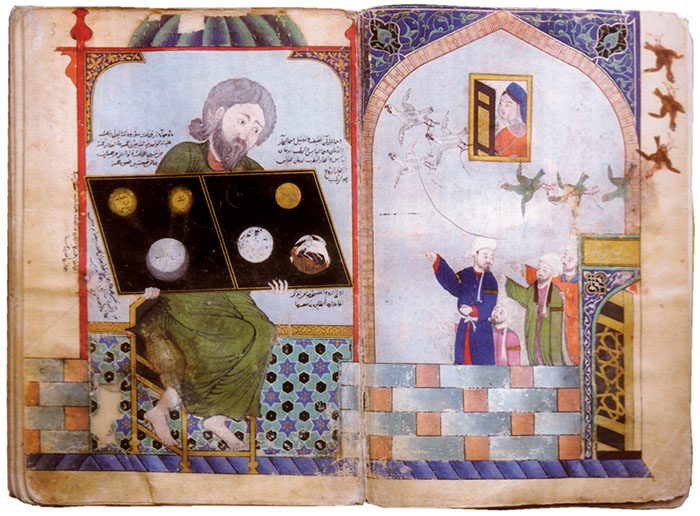

Alison: Alchemy is known to many different cultures, such as the Chinese, the Indian. It is a wisdom of transformation. As the tenth-century Islamic alchemist and lover of the Egyptian temples, Muhammad Ibn Umayl [/], says, alchemy can be known by people of any religion.

David: What makes the Egyptian wisdom of transformation unique and different from others?

Alison: I can’t speak for the others, but the Egyptian tradition is rooted in time, in the passage of time and continual transformation that we have been talking about. The alchemists call their work ‘the work of a day’.

David: The transformation is from what to what?

Alison: The Egyptians called it ‘the way of the green bird’. It’s initially the transformation of the human up to the seventh hour, which is the same as the transformation of copper alchemically, bringing all the human passions into harmony and balance. It’s the birth into our golden divine nature, the second birth, in the ninth hour. Then it’s the unification of our spiritual and our human natures at the close of day.

But alchemy is not only about natural cycles and linear development. It’s about spiritual transmutation, making manifest the eternal within life’s ever-renewing forms. Transforming copper to gold is also at the heart of the alchemy that Rumi teaches. The Masnavi is steeped in Islam and the Quran, but running beneath the surface is this copper to gold alchemy, informing the whole structure of the work – particularly in Book 1 but also throughout all of the six books. It’s also the core of Ibn Umayl’s alchemy. He was a major transmitter of Egyptian alchemy to the West, much quoted by medieval European alchemists. And he quite explicitly says that his wisdom comes from the Egyptian temples.

David: You refer to this wisdom as ‘the Hermetic tradition’, linking it to its originator, Hermes Trismegistus. Can you tell us about him?

Alison: Yes, this ‘thrice-great’ Hermes is really a later incarnation of the Egyptian wisdom god Thoth and emerges in Roman Egypt, particularly as the revealer of wisdom to his pupil Tat in the collection of Greek treatises known as the Corpus Hermeticum. [4] These contain a lot of ancient Egyptian wisdom, though it is de-mythologised and expressed in a Greek idiom, so it’s hard to recognise the continuity – as happens, of course, also with alchemy.

In Islam, Hermes is identified with the Quranic figure of Idris, and his epithet ‘Trismegistus’ refers to three separate persons, variously interpreted. According to Abu Mashar, the ninth-century Muslim astrologer, there was a pre-flood Hermes who built the temple, or mountain, at Akhmim. The second Hermes lived in Babylon and his pupil was Pythagoras. The third Hermes lived after the flood in Misr (Egypt) and wrote a book about alchemy. It’s Hermes who teaches the alchemical ‘work of a day’ in the anonymous Arabic Epistle of the Secret, [5] which is widely quoted by alchemists from all eras.

Illustration from a transcript (1339 CE), probably written in Baghdad, of Muhammed ibn Umayl al-Tamimi’s book The Silvery Water. Ibn Umayl describes a statue of a sage holding the tablet of ancient alchemical knowledge, which he states stands in an Egyptian temple painted with murals of people pointing and eagles carrying bows. Image: Topkapi Museum, Istanbul, via Wikimedia Commons

David: Do we know how the transmission to Islam came about?

Alison: The simple answer is we don’t know how Muslims came into contact with ancient alchemy, nor all the other ‘sciences’ they rediscovered. They obviously did. But it’s not just a question of intellectual transmission in Hermetic alchemy. There has to be an inner connection, a subtle interplay between transmission and personal revelation. The twelfth-century Sufi mystic Shiḥab al-dīn Suhrawardi [/], maps a very interesting lineage. He describes how the ancient knowledge originally revealed by Hermes branched into two streams: an Eastern one and a Western one. Henry Corbin [/] did a lot of work on the Eastern stream. Not so well known, though, is the Western one, to which, according to Suhrawardi, belonged sages like Plato, Pythagoras, Asclepius and others, its perennial wisdom passing eventually to the Sufi masters Dhu’l Nun al-Misri [/] and Sahl al-Tustari [/].

Sufis, as you probably know, revere Dhu’l Nun as the transmitter of the Egyptian secrets. But here we get into extremely controversial territory, because he is said to have frequented the Egyptian temple in his hometown Akhmim (Panopolis), and could read hieroglyphs. Even more controversially, some say he was an alchemist. Long before Dhu’l Nun’s lifetime, Akhmim had a long tradition of alchemy, rooted in Egyptian temple wisdom, going back at least to the 4th-century Egyptian mystic and authority on alchemy, Zosimus of Panopolis [/], and his soror mystica Theosebia. Judging by references to Hermes in his treatises, Zosimus revered him, and in medieval Islamic alchemy, he and Theosebia become the bearers of Hermetic ancient knowledge, closely tied to the city of Akhmim.

David: You also show how this knowledge can be seen in the works of medieval Christian writers like Hildegard of Bingen and even Thomas Aquinas. How did it reach Europe?

Alison: Once again Dhu’l Nun is a hidden presence. By the early 10th century, Akhmim alchemy had reached Islamic Spain – Cordoba in particular. I touch on this at the end of my book when I mention the alchemical resonances in Ibn Masarrah’s [/] Sufism, and his links with Dhu’l Nun and Sahl al-Tustari. What I only discovered after completing the book was that the little-known alchemist Maslama b. Qasim al-Qurtubi also lived in 10th-century Cordoba. He had connections to Ibn Masarrah, and in his treatise Rank of the Sage, he directly quotes from a key Arabic alchemical text, the Book of Pictures, composed in Egypt and featuring Zosimus and Theosebia. Here is crucial evidence that Akhmim alchemy was already being transmitted in early medieval Spain. [6]

I then discovered on the internet a treatise by Ibn Bishrun, a pupil of Maslama, and to my surprise realised that the alchemy he teaches resurfaces in the much later Latin alchemical treatise, Aurora Consurgens [/], [7] which has been attributed to Thomas Aquinas. This is a revelation of female wisdom following the cycle of the hours. As I said, I didn’t know about Maslama al-Qurtubi when writing Hathor’s Alchemy, but I did set out the Islamic influence in Aurora Consurgens, particularly the Arabic text, Epistle of the Secret that I mentioned before.

It will take time before the full extent of the transmission to Spain, and then to Latin Europe, is understood, but a genuine connection with Akhmim alchemy, and ultimately with Dhu’l Nun, is starting to emerge. It may be a while but Suhrawardi’s Hermetic Western lineage will surely be vindicated!

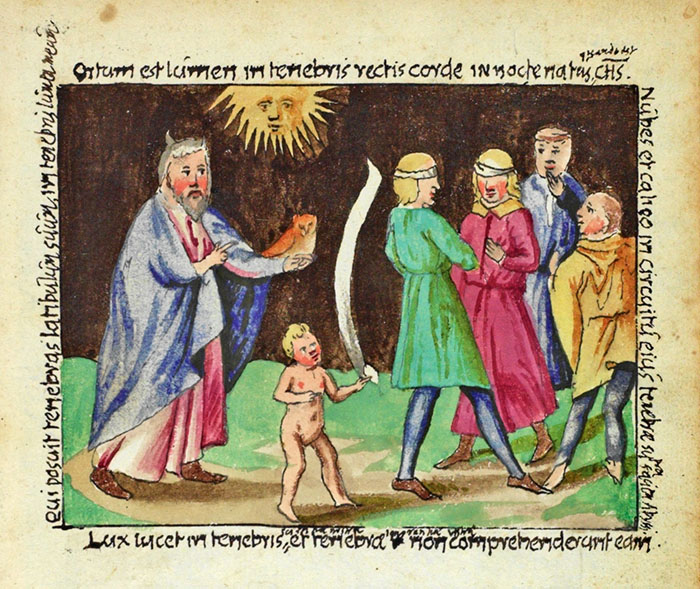

Alchemy’s saturnine black phase, as represented in the Latin Aurora consurgens attributed to Thomas Aquinas, and exactly replicating the teaching given by Hermes in the Arabic Epistle of the Secret from Akhmim. Here Hermes guides the blindfolded couple during their first union initiating the ‘work of a day’. Image: 17th century, courtesy of Glasgow University Library, Department of Special Collections, Ms. Ferguson 6, f. 236r

Contemporary Relevance

.

David: These technical details of transmission, tracking the passage of knowledge across cultural and religious boundaries, are fascinating. But what do you think this form of alchemy means to us today in the twenty-first century?

Alison: As Wisdom insists in Aurora Consurgens, the starting point of alchemy is everything around us. It can be tending a plant, it can be cultivating a garden, it can be cooking. Alchemy is seen everywhere.

David: Alchemy has as its premise that we humans need to evolve, and that we need to be purified. Is there a special wisdom that is attainable by recognising and going through the alchemical process?

Alison: I can only speak for myself. When I first started this journey into Egypt, I was at a very low point in my life. Coming into contact with Hathor, with this tradition, with this goddess wisdom, has helped me to grow into an understanding of myself both as a human being and as a spiritual being. It has been a healing journey. I think of alchemy as a medicine for the soul. It’s a journey which helps us understand who we truly are, spiritually, in our deepest essence.

David: Humans have gained extraordinary new knowledge by putting satellites into space and can now relate to the vast infinity of the physical universe in a way which was never possible before. How do you see the Egyptian vision fitting into this?

Alison: It seems to me that the message of all these new developments is that we have to develop inwardly into a new relationship with the cosmos, but in a different way from the Egyptians. What the Egyptian tradition can give us is nourishment for the soul, and can help us to develop that inner relationship with the cosmos we need, so that we can grow into a new understanding of our relationship with it. It’s an inner journey now. I’m not saying that the Egyptian way wasn’t an inner journey, but they perceived the cosmos in a different way.

I think we also need to remember the role of Hathor. Hermes is the messenger, the guide, but he is the guide through love, and she is the energy of love which is everywhere in the cosmos, if we can attune ourselves to it. It’s the attuning ourselves to this energy of love which is so fundamental in helping us to feel we do have a place in this new, infinite cosmos – that we belong here … because so often there’s a feeling of alienation.

David: What is the essential and enduring message of the ancient Egyptian wisdom?

Alison: That the whole point of the journey is to make the interior open, to bring forth our true self from within. In Hathor’s cult at Dendara, the spirit of it was to make the interior open, which is also the journey in Rumi’s Masnavi; it’s the Sufi journey of revealing the secrets of the heart. The essence of that journey is that from dawn to dusk there is an opening of the heart and the coming into manifestation of these inner mysteries. That’s what it is all about in the end.

Entrance to the tomb of Dhu’l Nun, transmitter of the Egyptian secrets, in the Southern Cemetery, Cairo. Photograph © Sam Gladstone

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner picture: Elaborately carved columns in Hathor’s temple at Dendara dating to the first century CE. The goddess faces on the columns were intentionally erased at a later date, indicative of hostility to Hathor’s transformative power. Photograph © Sam Gladstone.

First inset: A goddess named ‘She Who Vanquishes’ raises the sun from darkness, praised by the figures of ‘East’ and ‘West’, here celebrating the continuity and unity of the solar circuit. Photograph: AMR Picture Library.

Second inset: The golden mask of the boy king, Tutankhamun (c. 1341–1323 BCE), showing the upright cobra form known as the uraeus which symbolised royalty and divine authority. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons.

Our thanks to Alison Roberts for generously allowing us to use the images taken by herself and her son, Sam Gladstone. For more information on ‘Hathor’s Alchemy’ and other books by Alison, see Northgate Publishers.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] ALISON M. ROBERTS: Hathor’s Alchemy, Northgate 2019.

[2] JALALUDDIN RUMI: Masnavi, Book 5, verses 3854–9. Translation by Franklin Lewis in RUMI: Swallowing the Sun, Oneworld Publications, reprint edition 2013.

[3] ALISON M. ROBERTS: My Heart My Mother: Death and Rebirth in Ancient Egypt, Northgate 2000.

[4] See BRIAN COPENHAVER: Hermetica: The Greek Corpus Hermeticum and the Latin Asclepius in a New English Translation, Cambridge University Press 2008.

[5] This anonymous text has been edited, with German translation and commentary, by INGOLF VERENO in Studien zum ältesten alchemistischen Schrifttum: Auf der Grundlage zweier erstmals edierter arabischer Hermetica.

[6] An Arabic edition based on three manuscripts is available in the Corpus Alchemicum Arabicum series edited by THEODOR ABT and W. MADELUNG: The Book of the Rank of the Sage, Rutbat al-Hakim by Maslama b. Qasim al-Qurtubi, ed. W. Madelung, CALA IV, 2017. There will be a forthcoming English translation and commentary in the CALA series. A comprehensive edition from all the known sources is currently being prepared by Godefroid de Callataӱ and colleagues at Louvain University. Click here [/].

[7] See MARIE-LOUISE VON FRANZ: Aurora Consurgens, edited with a commentary, Inner City Books 2000.

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

The Zoroastrian Flame

Khojeste Mistree talks about one of the world’s oldest surviving religions and what we can learn from it in the present day

A Caravan on a Spiritual Silk Road

Warren Kenton on the profound wisdom of the Kabbalah

The Unity of Humanity

Professor Todd Lawson on the universal vision of the Qur’ān

Mysticism in Comparative Perspective

Professor George Pattison talks about the revival of a unitive approach

READERS’ COMMENTS

An excellent and most fascinating interview. it brought some understanding to the extensive pantheon of Egyptian Gods, but also placed in in line with those that ultimately see unity as the source of all.

I hope to find time to read more around this and the book itself

This article chimes with my personal experience and with the book that I wrote in 1997 wherein I place the 12 Step Programme (that was transmitted into Man’s experience in 1935) as a Sufi transmission.

http://lifeisreturning.com/2014/08/30/book/