Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 21, 2022

Spirituality and Self Development

Dr Renee Hattar talks about an innovative course in Jordan which explores universal spiritual values with young leaders

Spirituality and Self-development

Dr Renée Hattar talks about an innovative course in Jordan which explores universal spiritual values with young leaders

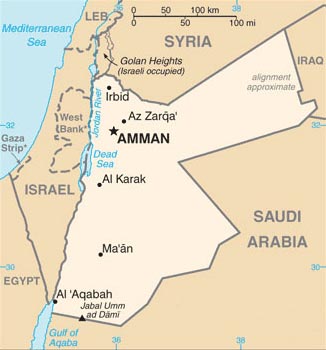

Jordan, a small country at the crossroads of the Middle East, has undergone huge changes in recent years, with the number of refugees now outnumbering its own population. In this article, we look at a bold project that aims to bring together young people within this melting pot, offering them a way of examining the common spiritual values underlying all the spiritual traditions. Elizabeth Roberts and Jane Carroll talk to its director, Dr Renee Hattar, about the aims of the project, and what has been learnt from the pilot scheme.

Dr Renee Hattar is the Director of the Royal Institute for Interfaith Studies (RIIFS) [/] based in Amman, Jordan. ‘Royal’ because it is one of many projects under the patronage of HRH Prince El Hassan bin Talal, who since the 1970s has gained an international reputation for his work on interfaith dialogue and peace-making. One of Renee’s tasks in recent years has been the development of a new approach to spiritual education that aims to find ways of discussing values and ethical principles with young people in a non-denominational context, not limited by the beliefs of any particular religion. The result is a pilot course entitled Spirituality and Self Development which has just run in Jordan with a cohort of about 20 young leaders drawn from a wide range of cultural and religious backgrounds.

Dr Renee Hattar is the Director of the Royal Institute for Interfaith Studies (RIIFS) [/] based in Amman, Jordan. ‘Royal’ because it is one of many projects under the patronage of HRH Prince El Hassan bin Talal, who since the 1970s has gained an international reputation for his work on interfaith dialogue and peace-making. One of Renee’s tasks in recent years has been the development of a new approach to spiritual education that aims to find ways of discussing values and ethical principles with young people in a non-denominational context, not limited by the beliefs of any particular religion. The result is a pilot course entitled Spirituality and Self Development which has just run in Jordan with a cohort of about 20 young leaders drawn from a wide range of cultural and religious backgrounds.

RIIFS was founded in 1994 and has evolved from being largely concerned with Muslim–Christian relations in the Arab world to an interdisciplinary institution which covers all aspects of cultural and civilisational interaction. Its underlying aim is the promotion of peace, both locally and globally. It is no coincidence, perhaps, that it is based in Jordan, a tiny state sitting at the heart of the Middle East. The country shares a border with Saudi Arabia to the south and east; Iraq to the northeast; Syria to the north, and the Palestinian West Bank, Israel and the Dead Sea to the West. The whole region has experienced radical and often violent change over the past sixty years, and as a result of its policy of welcoming people in need, Jordan has absorbed a huge number of refugees.

RIIFS is therefore working within the context of enormous social and demographic upheaval, where there is a real danger of extremist groups gaining influence, particularly over young people. “We had already taken a lot of Palestinian refugees in in 1948 and 1967,” explains Renee. “But we were living together very harmoniously until the first Gulf War. Then we started having other types of refugees – Iraqis, Syrians, Sudanese, Somalis, Yemenis. In 1990 we were three and a half million people. Now we are 11 million, and we have between 52 and 58 different nationalities living here.”

Some of these new arrivals are Jordanians who were living abroad and returned home, but there are substantial numbers from other countries, many of whom are traumatised by their experience of war and displacement. “Imagine all the changes that have come with these new people – economically, socially, religiously even. They are positive changes, of course, but huge ones. And they bring with them many problems – like the supply of water, for example.”

Za’tari refugee camp in the north of Jordan is the world’s largest settlement of Syrian refugees, with about 80,000 inhabitants. Set up in 2012 at the height of Syrian civil war, it has now evolved into a permanent settlement. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

Move computer mouse over image to enlarge

Cultural Context

.

The Spirituality and Self Development project has sprung directly out of RIIFS ongoing interfaith work in this rapidly changing situation. For many years the organisation has been conducting courses and research programmes at university level which focus on the shared values between religions. For example, they have looked at principles such as love and mercy in different religions, comparing what it means in one faith with what it means in another. These projects have in the past mostly been conducted online with international students. But the intention of this new project is to work with young people ‘on the ground’, aiming to facilitate ways in which these common ethical principles can be put into practice in people’s daily lives.

The course is actually part of a longer programme on self development for young people which aims to give them tools and skills to solve their own problems. On this, the students start by working on economic issues. They are shown how to propose a project, how to do a feasibility study, how to implement the project from A to Z, etc. Then in the second part, they move on to human rights and citizenship; how to get the right to vote; what are the responsibilities of citizens; what are their own rights, and so on. “All this is relatively easy to teach”, says Renee”. “A lot of it is a matter of developing skills. But where do all these concepts we talk about in the other modules – like equality and justice – come from, and how do they relate to the process of trying to develop ourselves, whether it is socially, individually, or within the family? In other words, what about the spiritual aspects of life?”

In Jordan, unlike the contemporary West, most people come from cultural backgrounds where religion is still at the centre of life. But this does not mean that everyone is fully engaged with their faith or that they have thought deeply about it. Many are just culturally religious, meaning, that they participate only at the level of ritual. So there is still a need to draw out the deeper meanings of the religions. RIIFS’ partners on the overall project therefore asked the Institute whether they could develop a course which would add a spiritual dimension to the existing training. In response, Renee and her colleague Dr Amer AlHalif designed the Spirituality and Self Development course as a training for trainers – that is, for people who have already taken on a leadership role within their own community. The idea is that they will go on to transmit what they have learnt to their own groups.

The students were selected through local on-the-ground organisations. There were some criteria; the group had to be gender balanced – that is, both men and women – and include both refugees and native Jordanians. They had to be from different backgrounds, different places in Jordan, and different religions. “People don’t necessarily state their religion in Jordan, but because we have such a tribal culture and such big family systems, it is possible to tell from the family name whether someone is Christian or Muslim or whatever, whether they are from the north or the south. The students were mostly between 25 and 35, and we set a maximum number of 15–20, because we have fairly intimate discussions and these would not work if there are too many in the group.”

The ancient city of Petra in the south of Jordan, constructed from 300BC onwards by the Nabateans people as the centre of their trading empire. Image: Nicolas Sanchez-Biezma/iStock

Finding Common Values

.

One of the novel features of the course is that it does not approach the question of values through the religions per se, but rather it tries to find ethical principles which are common to them all. Renee explains that this is an approach which RIIFS embraces in general. “People tend to speak or describe interfaith dialogue as a dialogue of dogmas, which is not possible. As believers, we all think we have the absolute truth – that we have the right religion. His Royal Highness Prince Hassan is always saying – and I think it’s true – that religions themselves do not dialogue: it’s people who dialogue. So the idea was to find a way of speaking about values where people could find common ground.”

In this respect, the geographical location of Jordan is a big advantage. Situated at the crossroads of three continents – Asia, Africa and Europe – there have been religions here dating back 3000 years. As Renee points out: “Islam has Judeo-Christian origins; Christianity has its origins in Judaism; Judaism has Babylonian, Sumerian, Egyptian roots. So you can’t just speak about the Abrahamic religions and ignore the chronology and the cultures that shaped them. And we believe that the message from all these religions is to have a humane value system and to spread peace on Earth. There is no such thing as a violent religion. It is true that we have violent interpretations of the religions, but that is not the same thing.”

However, Renee and Amer did not want the course to only speak about the Abrahamic religions. It also includes material from Far Eastern traditions, such as Buddhism, which is unusual in Jordan. And instead of discussing what kind of God people worship, they looked at the literature that influenced and was influenced by all these world religions. “So we were discussing what is called ‘the tradition of wisdom’. The idea of comparing religions is scary for many people. I mean, what are you comparing? Rather, we are interested in comparing concepts in these religions, and the idea of what makes a good man – or a good woman, because we started speaking also about why we don’t usually speak about women when we look at the role models of the saints.”

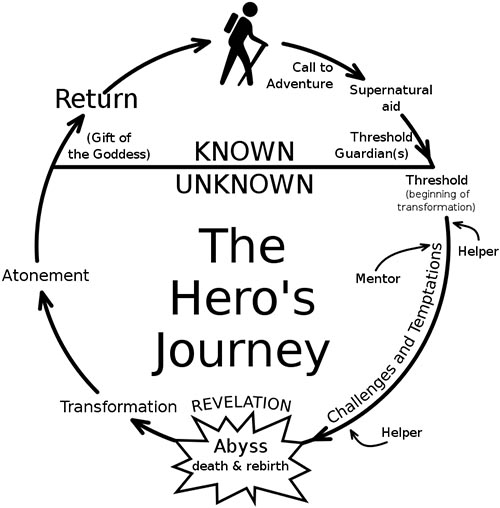

The Hero’s Journey as perceived by the American professor of comparative religion Joseph Campbell. He identified it as the universal ‘monomyth’ in which the hero sets out on an adventure, undergoes a critical ordeal and returns home transformed

A Universal Model of Development

.

To get outside the context of any particular religion, it was decided to use the model of ‘The Hero’s Journey’ as developed by the American writer Joseph Campbell [/]. This is a framework which he identified as embodying the deep inner journey of transformation which is at the heart of all spiritual traditions, based on his study of hundreds of myths from around the world. It delineates three main stages – Separation, Initiation and Return – divided into twelve sub-stages. “The point of the map”, Renee explains, “is to get people to identify with the story of the hero and ask: how can this be applied to my own life? We all live through the stages that it sets out, so how do we identify with them? How do we deal with death? With life? Are we still on the journey? Or did we just begin? Did we not even begin because we’re too scared?”

Just telling the students that everyone lives through these stages was initially surprising to them. Many of them were reluctant to speak at first, but then they loosened up and started telling personal stories about their life and their experience of death, that is, of a person they had lost. Then in the next stage of the discussion, they were presented with a set of worksheets with questions about some of the issues raised in the text, such as friendship, family values, and ways of life. For instance, in the first pilot course, they read the story of the Buddha, who had two distinct stages to his life: the first as a rich prince where he had everything he could possibly need materially, and then the other extreme, where he chose poverty but found spiritual fulfilment.

Renee and Amer asked the students to consider their own reactions to these two different ways of life. “It brought up issues of – well, we didn’t want to call it addiction to material objects, but perhaps, attachment to them. We feel that we need the newest phone, the newest TV set, the newest everything. But what if we started not caring about objects but caring about people? They found this idea confusing, because we all live in a capitalistic world where we feel we need to obtain things in order to feel happy. This is worldwide, of course, not just in Jordan; but here, the newer generation is more exposed to these capitalistic or economic ideas that their parents were. So, they had a lot of questions about what it means to care more for people. Someone said: I pray five times a day, but if I spend my money without helping people, does that make me a bad person? It brought up issues of compassion and empathy.”

It also brought up the economic reality of their lives, because many of the students were from very poor backgrounds where one’s status within society is equated with material possessions. The discussion was particularly challenging for those who came from the refugee camps. “And when we talk about refugee camps, we’re not just talking about the new ones for Syrians and Iraqis; we’re also talking about the Palestinian refugee camps, which have been there since 1967 and have now become cities. The people living in them identify as lower middle class to poor, so one of the issues at the beginning was that they were meeting ‘posh people’ from western Amman. But when we started speaking to them, eating with them and having coffee together, they realised: Oh my God, you’re normal people just like us!”

The Buddha story gave students an opportunity to open up about how hard their lives really are. “They would say: How can I be happy when I wake up in the morning and have to take a two hour transportation to get to my work? Or if I wake up each day with a problem on the street because I live in a camp? The other big issue was blame: they blame the country; they blame their families; they blame their friends; they blame their professors. So, getting over the idea that we were not just preaching or giving them lectures about what they should be doing – that we wanted them to identify personally with what we were explaining – was one of the hardest challenges.”

An interesting insight for Renee into the needs of the students came at the end of the first pilot session. “Some of them said to us: ‘You look so happy, and at peace with the world. Where do you get this sense of tranquillity?’ So, this was when we knew that the course had really worked, because this is not the kind of question you usually get asked. We understood that what they really wanted was the formula for happiness. And this is the whole point, is it not? It is what we all want.

From ‘The Life of the Buddha’. Prince Siddhattha encounters suffering in the form of an old man, a sick man, a corpse and a monk (on the right), and leaves his privileged life at the palace (on left) to embrace a life of poverty and spiritual practice. Image: Burma, c1800–20; British Library Or 14297, f.11

Problems of Terminology and Self-reflection

.

Another novel feature of the course is that it is conducted entirely in Arabic out of respect for the Jordanian context. This involved generating most of the material from scratch, drawing on the experience of other similar projects in the UK, Asia, Pakistan, Indonesia and in India, where there had been experiments with putting over spiritual values in schools. Dr AlHalif is an expert on comparative religions, specialising in Islam but having knowledge of other Asian traditions such as Buddhism and Shinto, whilst Renee specialises in Christian-Islamic relations, as well as having experience of using music to cultivate interfaith dialogue. So they have a broad base of knowledge. They took stories from the Bible and the Qur’an as well as from modern literature.

They trialled the material in three pilot courses, each of which took three days. For the first, they chose the story of the Buddha, but the reaction was not what they had hoped for. “It wasn’t that bad, but we felt that the students could not really identify with it. So for the second group we used a story that was closer to them, which was that of the Prophet Joseph. That was a big success because they already knew who he was, and being young people, they also identified with the idea that there was a woman trying to seduce Joseph, as that was their own stage of development in life. So it was fun. They found out that the story is much the same in Christianity and Islam, and of course it is in the Old Testament, so we were drawing from the texts of three religions at the same time. They also found that although there were small differences in the storyline, the values were exactly the same.”

One of the problems often encountered on courses like this is that people do not have the linguistic skills or educational background to discuss values or engage in self-reflection. But experience on other courses had led Renée to anticipate this; “For this very reason, in the worksheets we prepared, we laid out a set of values with every story and a set of terminology in Arabic, because some of the terms we used were new to them, or they were not clear about their meaning. For instance, how do you explain the word mercy? Mercy in Arabic – in fact, in Syriac and Hebrew as well – is raḥma. And raḥma has the same root as the word for ‘womb’. So we could work with all the connections that we have with that word – relationships to family, especially the women, nurturing, etc. Raḥma is also one of the 99 Names of God in Islam, which they were mostly familiar with.”

Other terms however, like, faqr, poverty, were not so clear. “Is poverty a value or is it a condition? What do we mean when we speak about a life of poverty within the religious traditions? These concepts can be a bit confusing for young people. So this was an area where we did a lot or work beforehand – linguistic work; theological work; historical work; and we also drew upon our social experience of working with groups in Jordan. It took us about six months to translate texts, to choose the terms we were going to include, to write good introductions. We wanted to simplify the process as much as possible.”

As for self-reflection, Renee acknowledges that this, too, was a major issue. “We find not only on this, but on all our courses, that people cannot express themselves as we expect them to, because they’re not trained to do so. People are trained to be good scholars – to study very hard, to enter university, to have a degree. Or they are trained to be a good man, a provider of the family, because men should do this; or a very feminine woman, a nice mother, a homemaker and so on. Or they are trained to be a good kid who doesn’t make any trouble or offend anyone – all the stereotypes we have. But they not trained to express their feelings about themselves. There is also a lot of cultural baggage: men are not supposed to cry; women or little girls are not supposed to shout or speak in a very high voice. So to tackle this problem, we applied social emotional learning methodology in the groups and used the technique of learning by play, for instance.”

Dr Amer AlHalif with students on a RIIFS course. Photograph: Courtesy RIIFS

Learning to Listen

.

Renee emphasises that it is important to see the course in its context, as the third of three parts. In the previous part the students had worked on citizenship and human rights, and this laid down some of the groundwork for the discussion. “They considered questions such as: how can you be a useful citizen in your own society and be productive – a stakeholder. We have rights, and we have to know what our rights are. But what are our obligations? How can we all contribute to the common good? The common good was a big issue. What is it? So they discussed practical issues like: why shouldn’t you throw papers and litter onto the street in your own neighbourhood? Why should you respect the law and not cross a red light? Is it just because the government will punish you and you have to pay a fine, or are there real reasons you shouldn’t, such as not wanting to hurt anybody – or yourself?”

People in the developed world tend to take such principles for granted. “But we have regular lives; we come to work in an office; we have our own car, so we pick up our kids on the way home and go back to a nice house. But refugees don’t have regular lives, and things are not that easy when you don’t have a car, when you don’t have a home with a garden, when you need to share everything with neighbours who all have major problems of their own. Also, you went to school in a rural area and didn’t go to university, so you have the problem of finding rewarding work when you don’t have a degree. And so on.”

Bearing all this in mind, and the question she had been asked at the end of the first pilot about happiness and tranquillity, Renee realised that people cannot just come to a course like this and start talking immediately about inner peace and spirituality. So, for the second pilot, she chose a place with a green setting. They found a location outside Amman where it was very peaceful, and each day they started with some breathing and musical exercises, which is an area that Renee has particular expertise in; her PhD in Peace Studies from the University of Granada focussed on music as a way of cultivating dialogue between different faiths. “The exercises helped them to separate themselves from all the fuss of the morning – the problems they had just had when they entered the traffic, the fight with their mother, the fight the neighbours had which meant that they couldn’t sleep, etc.”

The students were also asked to turn off their mobile phones. “And this was a big deal, believe me! On the first course, half of them could not tolerate this. What if somebody calls me? What if somebody sends me a WhatsApp? They’re really addicted. We are all addicted! We had to persuade them that it is not the end of the world to turn the phone off for fifteen minutes. It’s a spiritual practice just to concentrate on something else – to sit together until you find focus. I told them: this is how prayer should be. You want to speak to God? So did you really listen to what was being said?

Listening was probably the biggest challenge in everything that we did. We all want to talk about something, but how carefully do we listen? So after we had done some breathing and put away our phones, students entered into a different mindset from the crazy life they usually have – and we started the training. It made a huge difference.”

Renee with students on a RIIFS course. Photograph: Courtesy RIIFS

Spirituality versus Religiosity

.

The three pilots were a learning curve for both the students and the tutors. Issues came up which Renee and Amer did not even imagine were there when they did the initial preparation, and which they could never have picked up by just doing surveys or questionnaires. One of the big questions was the difference between religiosity and spirituality.

In the handout for the courses, therefore, this issue was explicitly tackled, and the following definition given:

Spirituality relates to the spirit and reflects the intangible aspect of the human being, which includes a divine aspect that goes beyond the knowledge of man. A spiritual person is one who lives a special relationship with God and seeks to extend peace and tranquillity and obtain a kind of special knowledge, called gratitude and illumination, which leads the way in life and makes a person feel a kind of unity with all beings and objects.

To get this idea over to the students, Renee took a pragmatic approach: “Students would say: I pray five times a day, but I don’t have that inner peace you’re telling me about. I would respond by saying: if you pray five times, do you give it time, or do you just do it as a ritual and say, I did it and I have no more obligations? This is a bit of a sensitive issue, because it might seem as if you’re questioning their faith and its rituals, but actually, you are just asking: Are you doing it the right way? Do you take time to contemplate so that you really have this communication? Do you question yourself about what you did well, and ask how you could do it better?” She would also ask the students about their relationships with others. “How do you treat other people? Because if you don’t love yourself, how are you supposed to love others?”

Another important conversation was the difference between the kind of work required on the other parts of the course and the inner work and commitment demanded on this one. “We said to them: this is not something you can just acquire some skills in, like understanding law or the obligations of citizenship. You have to believe in this yourself and work on yourself in order to work with these concepts with other people.”

One of the fruits of the pilot scheme was the production of a training manual which embodies all the knowledge gained through the three courses. The next stage is that the students go on to teach it to others. But this has not yet been implemented because of problems related to Covid. It is hoped that it will happen in the next few months, and then the organisers will have a better idea of what additional support might be needed. The longer course is also running again, and the students are currently in the second part, discussing citizenship. So soon there will be a second set of students who have gone through what is clearly a very educative and valuable experience.

The young people of Jordan, living in conditions of enormous tension and change, clearly have a special need for this kind of open-minded education. But one cannot help feeling that young people everywhere – even, or perhaps especially, in Western countries – would also benefit from exploring these universal values in such a thoughtful and practical way.

HRH Prince El Hassan bin Talal delivered the 50th Anniversary Lecture of the Beshara Trust in May this year. To hear his talk, entitled ‘Unity in Humanity? Where Two Hands Meet’, click here [/]

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Banner: Renée Hattar delivering a Prayer for Humanity. Image: YouTube [/]

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Mysticism in Comparative Perspective

Professor George Pattison talks about the revival of a unitive approach

Father Bede Griffiths and His New Vision of Reality

Adrian Rance-McGregor reviews the life of a pioneering 20th-century mystic, and the message of one of his most insightful books

Towards a Deeper Spirituality

The Reverend Peter Dewey looks back on a lifetime working with interfaith projects

World Literature Decentered

Ian Almond talks with Jane Clark about a more inclusive approach to comparative literature, and the cultural traditions of Turkey, Mexico and Bengal

READERS’ COMMENTS

Heart warming. A similar course should indeed be part of the core curriculum of our universities and colleges.

The Hero’s journey as explained by Dante’s universal search for completion.

Bonjour,

Besharamagazine édite un bulletin ?

Salutations.