Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 24, 2023

The Cosmos in Stone: the Ascent of the Soul

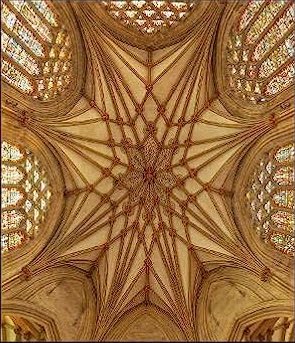

Artist–geometer Tom Bree explores the symbolism embodied in the design of two major centres of worship – the Dome of the Rock on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount and Wells Cathedral in Southern England

The Cosmos in Stone: the Ascent of the Soul

Tom Bree compares the meaning embodied in the geometry of two important religious buildings – the Dome of the Rock on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount and Wells Cathedral in Southern England

Tom Bree is an artist–geometer who for many years has been researching the sacred principles which underlie some of the great historic buildings of the world. He studied with Professor Keith Critchlow at the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London, where he himself now teaches. His recent book The Cosmos in Stone: Sacred Geometry of a Master Mason [1] is a magnus opus in which he explores the intricate and harmonious geometry behind the structure of Wells Cathedral in Somerset UK. In this article he suggests that there is a connection between some aspects of the cathedral’s design and the geometry of the Dome of the Rock on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem; both buildings, he shows, emphasise the vertical axis, and thus symbolise the ascent of the human soul to the divine.

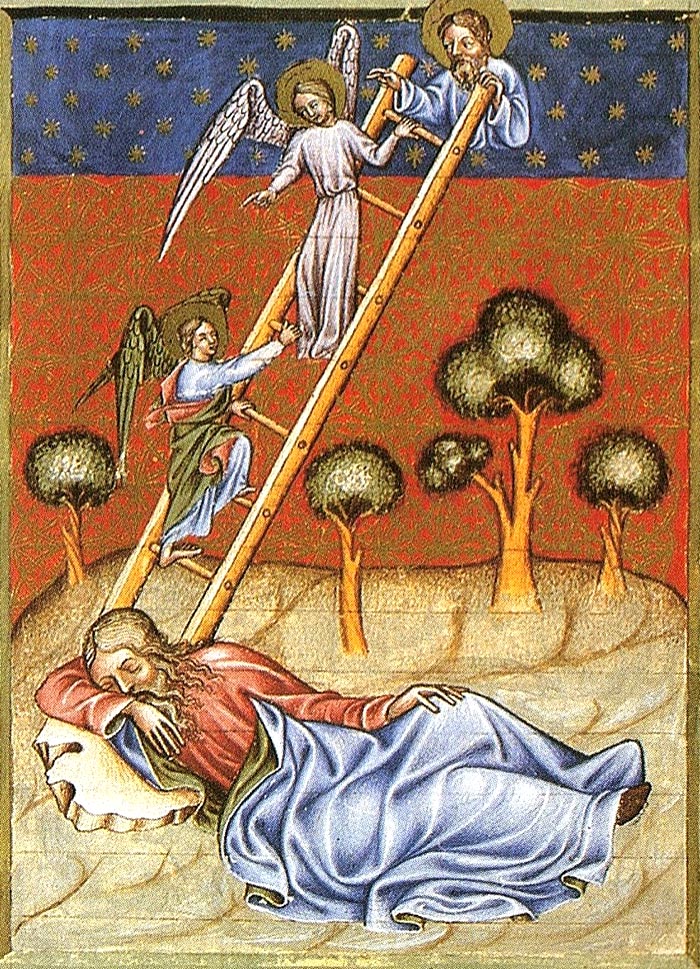

The symbolism of the soul’s ascent can be found in many different religious and philosophical traditions, such as in the Torah’s description of Jacob’s ladder or in the contemplative use of the Sephirotic tree-of-life in the Kabbalistic traditions of Judaism. In the Christian tradition, St Paul’s description of his ascent to the third and highest heaven in 2 Corinthians,[2] and more generally, the key influence of Platonism on Christianity, has led to various stories relating in some way to the soul’s ascent. These include Dionysius’ The Celestial Hierarchy and Dante’s Divine Comedy as well as Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy.

The symbolism of the soul’s ascent can be found in many different religious and philosophical traditions, such as in the Torah’s description of Jacob’s ladder or in the contemplative use of the Sephirotic tree-of-life in the Kabbalistic traditions of Judaism. In the Christian tradition, St Paul’s description of his ascent to the third and highest heaven in 2 Corinthians,[2] and more generally, the key influence of Platonism on Christianity, has led to various stories relating in some way to the soul’s ascent. These include Dionysius’ The Celestial Hierarchy and Dante’s Divine Comedy as well as Boethius’ The Consolation of Philosophy.

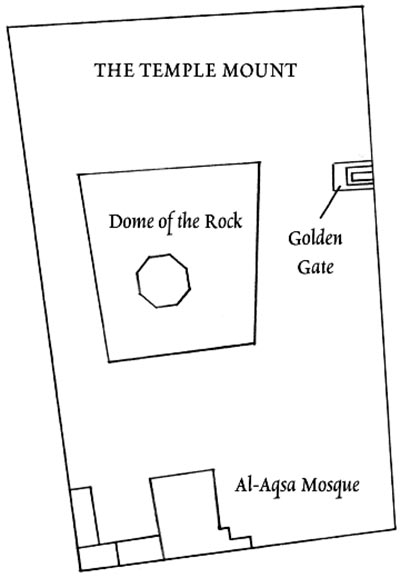

An Islamic story involving ascent is the Prophet Muhammad’s Night Journey, or miʿrāj, in which he ascends through the seven heavens, within each of which he meets various other Islamic prophets. There is an Islamic building that is associated with this particular storyline – The Dome of the Rock in the Al Aqsa Mosque compound on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount. Analysing the design of this ancient building according to the principles of sacred geometry reveals that it could be described as emphasising a vertical axis – which, as I will show, symbolises ascent – within its very structure. I will go on to suggest that a symbolic layout of the same sort can also be recognised in the design of the chancel and chapter house area of Wells Cathedral, the first gothic cathedral to be built in England.

The Night Journey of the Prophet Muhammad. Image courtesy of Jane Clark

The Relationship between Heaven and Earth

.

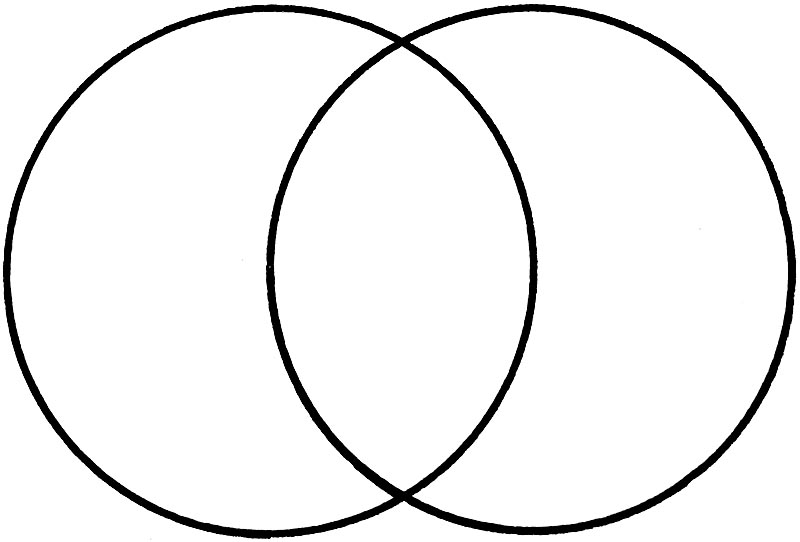

Before embarking upon a detailed analysis of these buildings, it is necessary to give a little background. When geometric symbolism is used as a way of contemplating the relationship between heaven and earth, there are a variety of different geometric forms that can be used. If two circles are overlapped in such a way that the circumference of each circle passes through the centre of the other circle, a so called ‘vesica pisces’ is produced. The Vesica Pisces is the name given to the area where the two circle’s overlap. It symbolises an area of mediation or relationship between polar opposites.

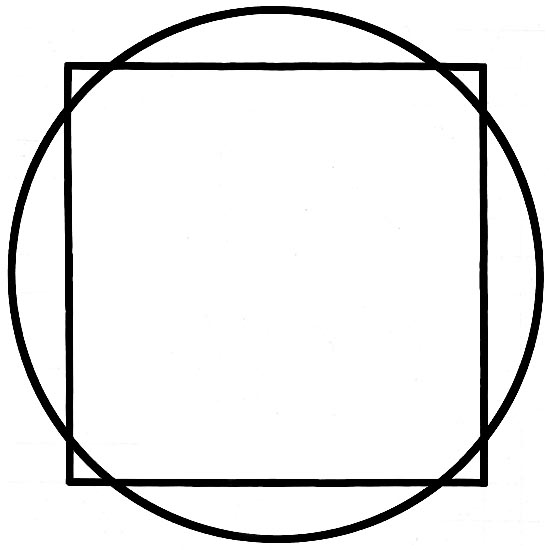

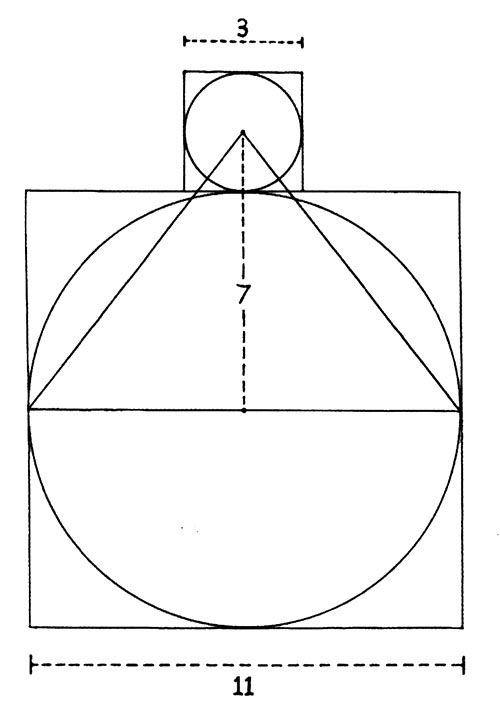

So, in this sense one of the circles symbolises heaven and the other earth. But in another use of geometric heaven/earth symbolism, the circle symbolises heaven whereas earth is symbolised by a square. This is the case within the symbolic process known as ‘the squaring of the circle’. The square is derived from the circle, which has either the same peripheral measurement or the same area as the circle. This is understood to present an image of balance or likeness and thus ‘relationship-ness’ between the circular heaven above and ‘four corners’ of the earth down below.

Another example of heaven–earth symbolism can be seen in the use of the cross as a form that presents an interaction between a vertical and a horizontal line. The vertical line could be described as an ‘ontological’ axis, whereas the horizontal line symbolises a ‘cosmological’ expansion outward from the vertical axis into the ‘horizontal’ material world. A useful way of seeing such a metaphysical symbolism in a more direct and material form is to understand the ontological axis as the invisible or indefinitely thin vertical line about which a spinning top revolves. The material form of the spinning top is then the visible cosmos and its turning movement presents an external image of the inner workings of the hidden ontological axis.

This is not entirely dissimilar to Plato’s description of time as a moving image of eternity. This can be seen very nicely in the most common present-day image of time, the clock. The turning hands on a clockface obediently externalise the knowledge of the clock’s hub, which is itself at the unmoving centre of the clock’s circular face. The hub could accordingly be described as the ‘unmoved mover’ because it is stationary at the centre of the face – and therefore outside of the cycle of time – yet, concurrently, it is also turning and causing the clock’s hands to externally express a sequential image of time.

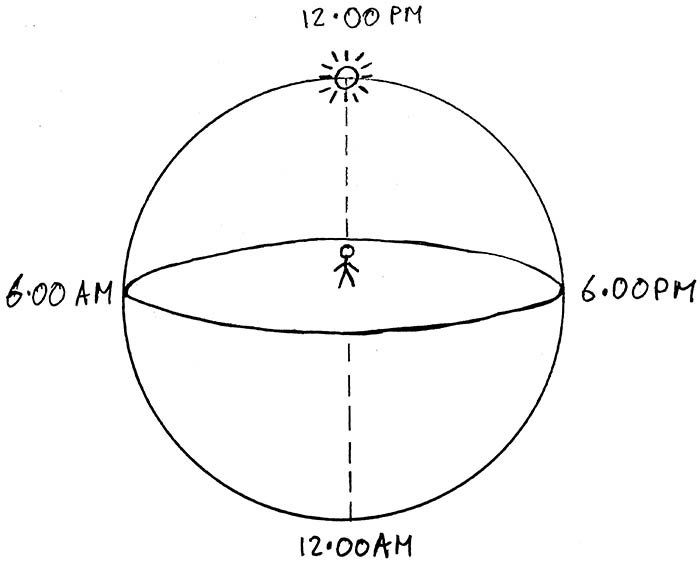

In the same way, the soul’s descent into the underworld or ascent through the heavens is very readily symbolised by a vertical axis. Such an axis could be looked upon as piercing the central point of a circular earthly plane: indeed this would be at the central point of a circular earthly plane that is demarcated by our visible circular horizon. Each one of us is accordingly forever located at such a central point because wherever we move in any direction the circular horizon moves with us. So, we are forever physically present at the ‘centre of the world’ from where we bear witness to the workings of the world around us.

Further, if one then imagines that the horizon encircling us is the equator of a sphere, then it is possible to perceive the blue sky, stretching upwards from the horizon, as being the sphere’s upper half or hemisphere – in other words the ‘dome’ of heaven. There is then an imagined hidden hemisphere below the circular plane upon which we stand, and this is the underworld through which the sun passes during the night-time having encircled the upper hemisphere during the hours of daylight.

With such an imaginal way of seeing things we become the still point, like the clock’s hub, about which the sun is moving and marking out time. It could also be said that our vertical presence – with head up in heaven and feet down on earth – reflects a miniature image of the sphere’s ontological axis about which these circular heavenly cosmic movements are effected. The sun’s ascending and descending movements, between the sphere’s zenith and its nadir, accordingly become external cosmic images of similar movements taking place within the soul – much like the ascending and descending angels that Jacob saw in his dream of the ladder. In this sense the heavenly bodies present the soul with an image of its own inner workings. Thus to look out into the universe, or ‘macrocosm’, as far as it is possible for the human eye to see, becomes analogous to looking inwards toward the deepest and most hidden reaches of the ‘microcosmic’ human soul.

Ascent as a Ladder

.

A vertical axis, therefore, inevitably implies movements of ascent and descent and in this sense it can also be viewed as a ladder. Such a ladder may have a particular number of rungs, and within the sacred traditions the most common is perhaps seven, which together symbolise the seven planetary spheres or, alternatively, in the ancient Sumerian poem, the descent of Inanna through seven levels into the underworld. If it is an ascent through the seven planetary spheres then the eighth sphere of the fixed stars and the ‘first moved’ ninth sphere can be added so that the number becomes nine.

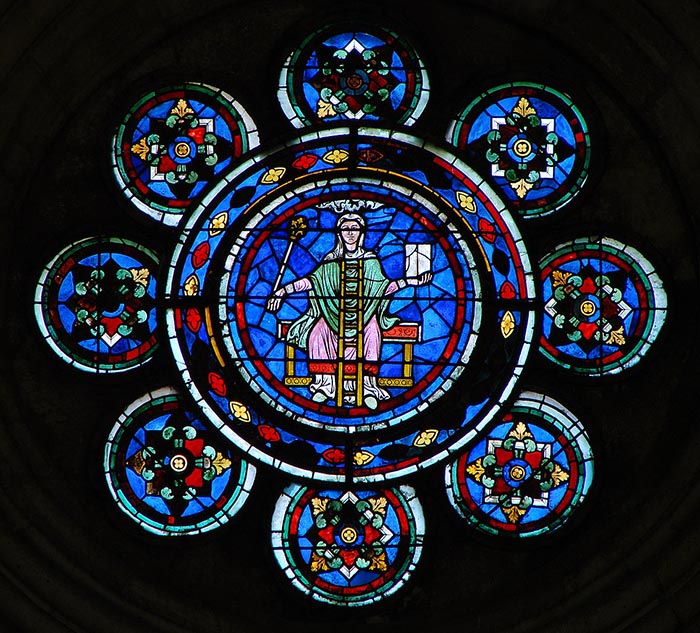

A beautiful example of this is the depiction of Boethius’ Lady Philosophy in the centre of the north rose window at Laon Cathedral in France. The story behind this is that at the beginning of the Consolation of Philosophy, Lady Philosophy presents herself to a distraught Boethius as a consolatory inward ladder of ascent through which his soul can look upwards and rise above and beyond the corrupt and tragic predicament of his condemned state. At the time, through having fallen out of favour in the grimy world of politics, Boethius was imprisoned and awaiting execution, and this was the setting in which his providential meeting with Lady Philosophy took place. It subsequently led to him writing one of the most important and read books in the whole of the medieval Christian era. The message is that it is often when the soul reaches its very lowest point that a vision can be witnessed which raises it up aloft, into the heavens.

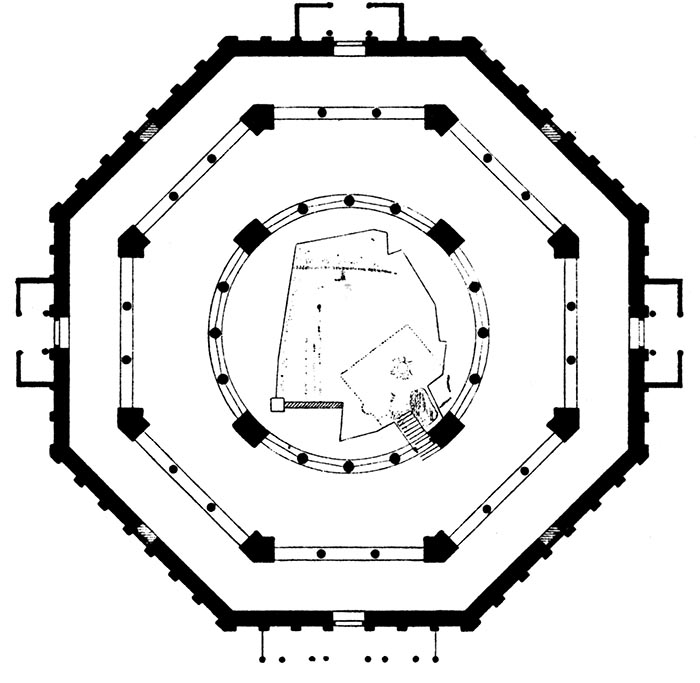

The Dome of the Rock can be described as ‘centrally planned’ in the sense that its architectural plan (i.e. its ground plan) emphasises a central point. This is because it is octagonal.

This is notable, because the places of religious worship used in the three Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity and Islam can generally be described as emphasising a horizontal ‘linear axiality’ rather than a single central point. This is aided by the fact that churches face eastwards towards the rising sun and morning star, whereas synagogues and mosques respectively face Jerusalem and Mecca which in geographical terms are the focal points for these two religions.

In each of these examples there is a focal point, far off in the distance, towards which the place of religious worship is orientated. This naturally emphasises a linear or ‘axial’ relationship between the place of worship and a point in the distance, and this relationship will also generally show itself in the design and layout of the building. But this is not the case with the Dome of the Rock, which is a shrine rather than a mosque. It is true that there is a very early mihrab in the cave (the Well of Souls) below the rock, but this is not the main focal object of the building. Rather the central focus is the rock itself, which is at the centre of the building directly underneath the dome. This means that the building’s ‘focality’ is centrally located and so the rock becomes the ‘immanent centre’ rather than a point that ‘transcends’ our visible horizon.

But having said this, it could be suggested that there is actually a linear axiality that is expressed by the centrally planned architecture, but this is vertical rather than horizontal. In this view, the rock is the starting point of a vertical axial movement upwards towards the dome which symbolises the heavens. This movement naturally reflects the Prophet Muhammed’s miʿrāj.

During the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1187) the Dome of the Rock was made into a church and was referred to by Crusader culture as ‘The Temple of the Lord’. This was in recognition of the belief that it stood upon the original site of Solomon’s Temple. Another interesting association is that it was also understood by Crusader culture to be the place where Jacob had his dream of the ladder. This event had no prior association with Jerusalem, and indeed the relationship was denied by the Christian Pilgrim John of Würzburg in his 12th century Description of the Holy Land: [3]

… with all respect to the Temple, this [its being the site of Jacob’s ladder] is not true, although the following verse is written there:

‘Jacob, this thy land shall be, And thy children’s after thee.’

But this did not take place here, but a long way off, as he was on his way to Mesopotamia. (p. 14)

The point here is that despite the religious usage of the building briefly changing from Islam to Christianity, within the understanding of Crusader culture the association with the soul’s ascent remained in place.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre

.

The other famous centrally-planned building in Jerusalem forms the western end of the church of the Holy Sepulchre. This focal area of the church – the Anastasis – is understood to be the place where Christ was interred after his crucifixion and from where he was resurrected. Again, it is a centrally planned building with a dome on top, with the focal point lying at the centre of the building down below the dome in the form of the shrine or ‘aedicule’ where Christ’s body was interred after the crucifixion.

The aftermath of the crucifixion is symbolically ‘vertical’ insofar as Christ first descends into Sheol for the Harrowing of Hell and then re-ascends and resurrects on the third day. Intimately related to the symbolism of the cross and the crucifixion is the association of Christ’s ascent with the image of an ascending serpent, and this still persists today, as can be seen by the fact that both of the Biblical readings concerning the ‘ascending-serpent’ are read on the Feast of the Holy Cross on September 14th. The first reading is the Old Testament description of Moses raising a serpent in the wilderness.[4] The other one is from the Gospel of John in which Christ associates his resurrection and ascension with Moses raising the serpent.[5]

The further reading on the feast of the Holy Cross is St Paul’s description in his letter to the Philippians of Christ’s salvific humility as understood through his ‘kenosis’ or ‘self-emptying’ which thus leads to his exaltation. One interpretation of these two related stages is that they can be understood symbolically as a descent followed by an ascent. In this sense Christ’s ‘kenotic’ descent to the ‘lowest point’ – or ‘the heart of the earth’ as it is described in Matthew 12:40 – subsequently leads to his exaltation to the highest point. St Paul effectively describes this in another of his letters (to the Ephesians) through a meditation on Psalm 68.

But unto every one of us is given grace according to the measure of the gift of Christ.

Wherefore he saith, When he ascended up on high, he led captivity captive, and gave gifts unto men.

(Now that he ascended, what is it but that he also descended first into the lower parts of the earth?

He that descended is the same also that ascended up far above all heavens, that he might fill all things.) [6]

Wells Cathedral

.

Returning to the Dome of the Rock, and the brief period of time during the 12th century in which it was used as a Church, there is a fascinating possibility that its ground plan was symbolically incorporated into the design of the first English Gothic cathedral at Wells in Somerset. This is feasible because at the time when the cathedral was first built in 1176 both the Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque would have been considered to be Christian buildings in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. A key element of this religious mix – in the sense of ‘Christianised’ Islamic buildings – is that both buildings on the Temple Mount were understood symbolically, by Crusader culture, to be images of the old Jewish Temple of Solomon; the Al Aqsa Mosque was known as the ‘Temple of Solomon’ and as already mentioned, the Dome of the Rock was the ‘Temple of the Lord’. The Knights Templar were based in the Al Aqsa Mosque and indeed this is seemingly how they came to be known as the ‘Knights Templar’; the Order’s original title was ‘The Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ’.

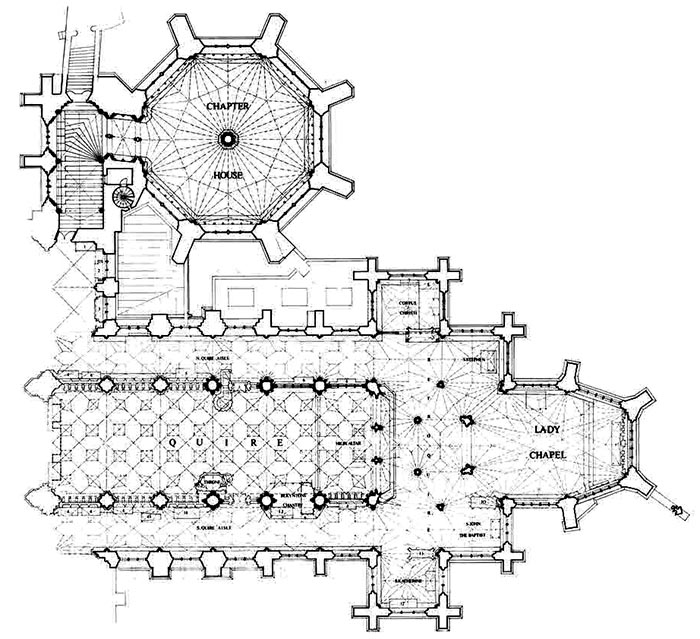

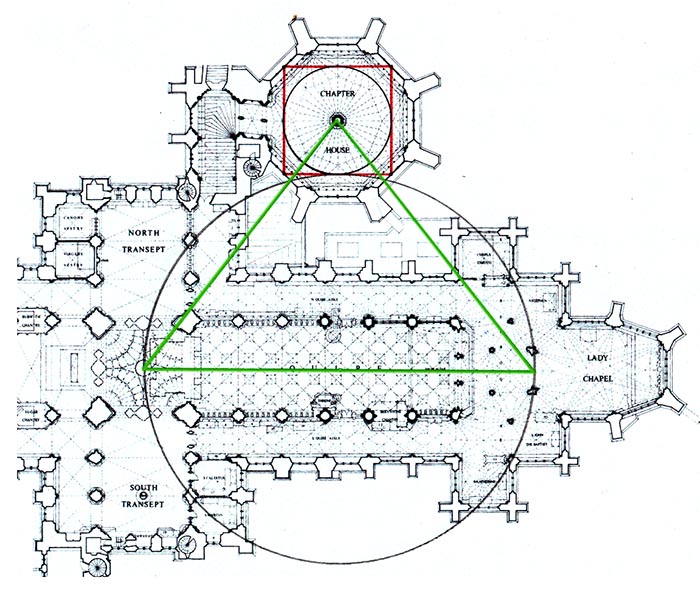

The topographical layout of the Temple Mount was the same in the 12th century as it is now, with the Dome of the Rock – which, as we have said, is an octagonal building – lying to the north of the Al Aqsa. A layout of this sort can also be recognised in the design of the chancel and chapter house area of Wells Cathedral, where there is an octagonal chapter house immediately to the north of the quire which forms the liturgical heart of the cathedral. This quire is the same shape and size as the biblical description of Solomon’s Temple, which in the Book of Kings is depicted as having a rectangular ground plan that measures 20 x 60 cubits – exactly the dimensions of the Wells’ quire.[7]

The Ascent of the Soul as the North

.

Another consideration is that these two elements in the Cathedral’s design are also connected by the ancient understanding that the direction ‘north’ symbolises the soul’s ascent into heaven. This understanding can be seen in the many descriptions, within various different traditions, of a ‘polar’ mountain that is in the far north. The summit of this ‘northern mountain’ can be understood cosmologically as the celestial north pole which is the central point in the night sky around which the fixed stars circulate. In Jewish scripture it is Zion – the ‘highest point’ – described at the beginning of Psalm 48: ‘Mount Zion in the far north is beautiful and high’. This polar mountain is also described in Isaiah 14:13 as the ‘mountain on the farthest sides of the north’ and according to medieval Christian cosmic mythos it is the highest point to which Lucifer, the fallen angel, ‘egoically’ aspires towards elevating himself. But his hubris causes him to fall ‘southwards’, as it were, to the centre of the Earth or Sheol which, as mentioned earlier, is the ‘lowest point’ to which Christ must descend for his harrowing of hell.

The polar opposition of the movements of Christ – the ascending serpent – and Lucifer – the descending serpent – lies in the fact that, whereas Lucifer hubristically attempts to elevate himself to the highest point – and thus falls to the lowest point – Christ voluntarily descends to the lowest point, becoming completely empty of any egoic self-interest, which thus leads to his exaltation to the highest point. In other words…

For those who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.[8]

This correlation of ‘north’ with ascent is represented by a cosmological diagram –the Earth–Moon Pyramid diagram – which my analysis indicates may well have been used in the design of Wells Cathedral. An introduction to this diagram briefly takes us to the English New Age scene of the late 1960s and early 1970s. My geometry teacher, the late Professor Keith Critchlow, was an old friend of the maverick counterculture writer and artist, John Michell. Critchlow’s profound focus upon sacred geometry rubbed off on Michell, and around 1970 Michell came up with this Earth–Moon diagram that appears to have also been known and used in the ancient and medieval worlds. For example, Michell presented good circumstantial evidence, based on simple and concordant geometry, arithmetic and metrology, that the diagram underlies the designs of both the Great Pyramid in Egypt and Stonehenge in the south-west of England.

In The Cosmos in Stone, I have presented more circumstantial evidence that the diagram was also known by some of the Gothic cathedral designers. I suggest that it was used in the design of Wells, which is of course not far from Stonehenge, and also appears to have been used in the building of two other English Gothic cathedrals, those of York and Southwell.

Unfortunately, the antagonistic relationship between Michell and academic archaeologists appears to have led to this diagram not coming to much prominence in the wider academic world, even though it is highly concordant in its mathematical relationships – albeit only if the so-called ‘English mile’ is the unit of measure that is used to make the calculations. This is a large subject which I cannot go into here but it is well-developed in my book.

The diagram involves the relationship of size between the Earth and the Moon, which then generates a particular type of triangle that is also found in the cross-section of the Great Pyramid. The way in which the diagram appears to have been used in the design of Wells Cathedral is such that the quire – the very heart of the cathedral – is located within the earth circle and the octagonal chapter house is at the centre of the moon circle.

Thus there is a suggestion that the way in which the quire, at the heart of the cathedral, relates to the octagonal chapter house on its north side symbolises an ascent northward from the central place on earth up to the moon and thus to the heavens. A particularly happy synchronicity in relation to the diagram is that the pyramid triangle has a height of seven units, and so therefore the symbolic ascent of the triangle, from its baseline up to its apex, consists of seven steps.

Being in the ‘Here and Now’

.

The key point to take away from all of this is that the physical experience within our immediate spatial surroundings, as well as in relation to the wider cosmos, plays an essential part in the soul’s inner life. To orientate oneself and one’s architectural designs according to the the directions of north, south, east and west is to place the soul at the ‘centre of the world’ in the ‘here and now’. To have one’s head up in the starry heaven and feet down on the sacred earth is to embody the spiritual hierarchy or ladder within which each rung plays its own particular and essential part in the soul’s ascent. And to design one’s architecture according to the eternal and unchanging truths of geometry is to use boundaries as a way of contemplating the boundless.

Tom’s new book, The Cosmos in Stone – Sacred Geometry of a Master Mason (The Squeeze Press, 2023) goes into all of the subjects that have been mentioned in this article. The book is printed with full colour and contains over 400 images and diagrams.

Tom’s new book, The Cosmos in Stone – Sacred Geometry of a Master Mason (The Squeeze Press, 2023) goes into all of the subjects that have been mentioned in this article. The book is printed with full colour and contains over 400 images and diagrams.

There are also various online talks on his YouTube channel [/] plus three talks on other websites:

Dante’s Journey in Gothic Cathedral Design [/],

Geometry and Cosmology in the Design of Wells Cathedral [/],

Greenness and the Golden Ratio [/].

Tom Bree is a geometer-artist who trained at the Prince’s Foundation School of Traditional Arts in London with Keith Critchlow. He now teaches regularly at the School, as well as teaching and lecturing for the Prince’s Teaching Institute, the Temenos Academy, West Dean College and the Royal West of England Drawing School. He lives in the city of Wells in Somerset

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: The Temple Mount in Jerusalem, with the Al Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock. Photograph: via Wikimedia Commons

Inset: Roof vaulting at Wells Cathedral.

All diagrams and images provided by Tom Bree unless otherwise stated.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] TOM BREE, The Cosmos in Stone: Sacred Geometry of a Master Mason (The Squeeze Press, 2023)

[2] New Testament, 2 Corinthians 12.1–10.

[3] JOHN OF WÜRZBURG, Description of the Holy Land, translated by Aubrey Stewart (Palestine Pilgrims’ Text Society, 1890) See online version on https://archive.org/details/cu31924028534323/page/n5/mode/2up.

[4] Old Testament, Numbers 21.4–9.

[5] New Testament John 3.13–14.

[6] New Testament Ephesians 4.7–10.

[7] Old Testament 1 Kings 6.2.

[8] New Testament, Matthew 23.12.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Mary, Seat of Wisdom and Mercy

Jane Carol explorese the vision of the Virgin Mary embodied in the structure and glass of Chartres Cathedral

Keith Critchlow: A Life Well Lived

Richard Twinch pays tribute to the teacher and sacred geometer who died on April 8th 2020

Calligraphy – A Sacred Tradition

Distinguished calligrapher Ann Hechle talks about her lifelong quest to understand the underlying unity of the world

A Thing of Beauty…

David Apthorpe extols the geometry and decoration in Sinan’s small masterpiece, the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Mosque in Istanbul

READERS’ COMMENTS

Beautiful images, very explanatory. Thank you.