Finance & Global Affairs _|_ Issue 17, 2021

African Apocalypse: Confronting the Injustices of the Past

Rob Lemkin and Femi Nylander discuss their new film on the realities and legacies of colonialism

African Apocalypse: Confronting the Injustices of the Past

Rob Lemkin and Femi Nylander talk to Jane Clark about their new film on the realities and legacies of colonialism in Niger

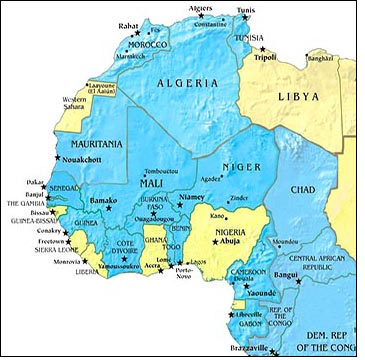

In recent years, there has been increasing awareness of the injustices done to indigenous and minority cultures, and the need to address them if we are to move forward as a human race. This new film, ‘African Apocalypse’, makes a major contribution to the debate by examining the history of just one country, Niger in Western Africa, from the point of view of its people, recording their stories of the conquest and its legacy. Jane Clark talks to its director, Rob Lemkin, and to poet-activist Femi Nylander – whose journey of discovery through the towns and villages of Southern Niger forms the narrative backbone of the film – about how they came to make it. You can see a trailer for the film here.

African Apocalypse tells the story of a journey made by British-Nigerian poet and activist, Femi Nylander, through Niger in West Africa, one of the poorest countries in the world. His aim was to follow the route taken by Paul Voulet, the military commander who led the original conquest of the country by France, and to learn about the process of colonialisation not from the official accounts or the perspective of the European conquerors, but from the people in the towns and villages along the highway.

African Apocalypse tells the story of a journey made by British-Nigerian poet and activist, Femi Nylander, through Niger in West Africa, one of the poorest countries in the world. His aim was to follow the route taken by Paul Voulet, the military commander who led the original conquest of the country by France, and to learn about the process of colonialisation not from the official accounts or the perspective of the European conquerors, but from the people in the towns and villages along the highway.

Launched to critical acclaim at the London Film Festival on September 2020, the film is directed by documentary film-maker Rob Lemkin, whose last work, Enemies of the People [/] (2010), won numerous awards and an Oscar nomination. On the one hand it is an exposé of the real story behind the European conquests, and on the other it is a moving portrait – an honouring – of the people of Niger. It is beautifully shot, immersing the viewer in the landscape and everyday life of the villagers in this arid, ancient land, designated by the United Nations as the ‘least developed’ in the contemporary world.

The film has been more than five years in the making, but its launch is remarkably timely, happening just as the Western world is embarking upon a radical reassessment of its colonial past. There is a growing awareness that, as Femi says: “We must confront the injustices of the past if we ever hope to be free for the future”.

Femi travelling in Niger. Photograph © LemKino Pictures / Inside Out Films

The Conquest of the Earth

.

There is no doubt that the underlying tale is grim; setting out from Timbuktu in 1898 with a force of 2000 men, Voulet’s mission [/] was to conquer the Chad Basin and consolidate French territories in West Africa. He ignored the order to make the mission one of ‘pacification’ and to work with local chiefs; instead he took the area by force, killing tens of thousands of Africans and looting, pillaging and raping wherever he went. When news of his campaign of terror reached France, there was a public outcry and an officer, Colonel Jean-François Klobb, was sent to relieve him of his command. But by this time Voulet was completely out of control, dominated by visions of glory and establishing his own despotic empire. When Klobb arrived, Voulet killed him before being killed, in turn, by his own men.

But the film begins not with Voulet but with a quote from Joseph Conrad’s famous novel, Heart of Darkness [1]: “The conquest of the earth is not a pretty thing when you look into it.” The central character in the book is Mr Kurtz, a successful ivory trader who becomes crazed in the jungle of the Congo, and whose story is told through the eyes of a young ship’s captain, Marlow, who travels upriver to bring him home. There are remarkable similarities between Kurtz and Voulet, to the extent that it would be tempting to see Voulet as the ‘real-life Kurtz’. But surely, I ask, Conrad’s novel was published in London in 1899 at the very moment when Voulet was wreaking his havoc, so it cannot have been directly influenced by events in Niger?

This is true, Femi and Rob respond, but they used Heart of Darkness as a pivotal element in the film because they believe that Conrad captured something archetypal about European attitudes and early colonialism; he himself said that “he put the whole of Europe into Kurtz”. The events that he portrays were enacted in real life not only in Niger but in many places: for instance, King Leopold II of Belgium’s behaviour in the Belgian Congo became so notorious that even at the time they were described as ‘crimes against humanity’. Starting with Conrad was a way of emphasising that the film is not just about one particular set of events in one country: it is about universal issues of empire and its legacy in the present day.

This is true, Femi and Rob respond, but they used Heart of Darkness as a pivotal element in the film because they believe that Conrad captured something archetypal about European attitudes and early colonialism; he himself said that “he put the whole of Europe into Kurtz”. The events that he portrays were enacted in real life not only in Niger but in many places: for instance, King Leopold II of Belgium’s behaviour in the Belgian Congo became so notorious that even at the time they were described as ‘crimes against humanity’. Starting with Conrad was a way of emphasising that the film is not just about one particular set of events in one country: it is about universal issues of empire and its legacy in the present day.

“The story that has been told of colonialism is of civilising missions, of helping people and being charitable”, says Femi. “The real history of the conquests, the real brutality of them, has been hidden, slid under the rug. Conrad himself spent time in the Congo, and his writing was undoubtedly coloured by what he saw there. He was one of the first people to describe the atrocities that were taking place, but he was a white man, and in the book you see events through the eyes of Marlow, who is European. You don’t get the African perspective at all, whereas our film makes sure that the Africans have a voice.”

But wasn’t Voulet’s behaviour an aberration? It was not generally acceptable, and when news of it reached France, there was a public outcry. “That’s true”, admits Femi, “but the mission itself was continued by one of Voulet’s officers, Lt. Pallier, and ended up with Niger becoming a French colony. The problem from the government’s point of view was not violent conquest as such: it was just that Voulet went too far – violence for the sake of violence – and then there was the scandal of him killing his senior officer. So the affair was covered up: they never set up a public enquiry into what had happened; documents were supressed, and the testimony of the Africans was never heard.”

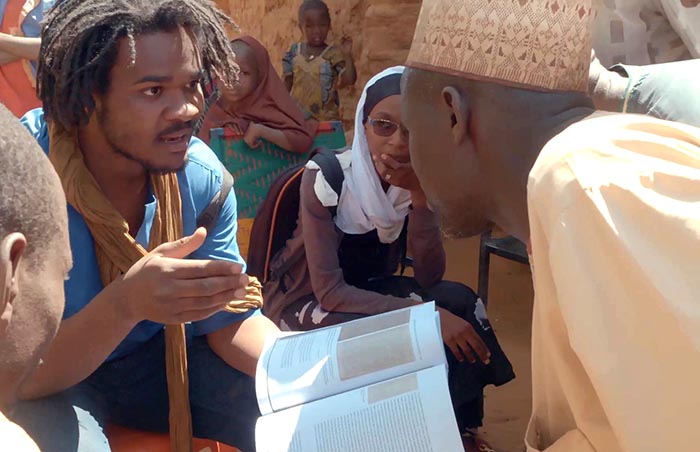

Femi in Dankori village, where Voulet is buried, reading villagers extracts from the diary of Captain Klobb, now kept in the French National Archives. Photograph © LemKino Pictures / Inside Out Films

Telling the Story

.

And that has remained the case until now. One of the most moving moments in the film is when a villager tells Femi: “No one has ever come before to ask about our history.” But the events of 1898 are still vividly remembered in the towns and villages of Southern Niger, where Voulet’s original route now forms the border between Niger and Nigeria. And within the one big story there are many individual tales of personal tragedy which have been handed down to grandchildren and great-grandchildren – heart-rending tales of unequal battles between Africans armed with spears and a French military equipped with guns and artillery, and the slaughter of women and children following defeat. The sites where these ancestors died are still remembered and cherished, and the anniversaries of the battles are the occasion for communal commemoration. Is it not remarkable, I ask, that it is all still remembered so vividly?

“Not at all,” Rob responds. “For us in Europe, these events feel like the distant past. History has moved on. But for these people, the conquest changed everything. There is life before Voulet, and life after Voulet. They remember the battles not as we might remember, say, the Battle of Waterloo, but because they were the beginning of the way things are now. They became subjugated to a foreign power and lost their autonomy and control of their own destinies in very fundamental ways.

“And although Niger became nominally independent in 1960, not much has changed for them. I don’t think we met a single person who would say that they are materially content with their lot. They face a host of problems on a daily basis: poverty, access to food, access to education, the lack of technological advancement. Yet in the past, although this is a very hard environment to live in, there have been civilisations in the region which have been much more confident and able to flourish. So these stories still have an enormous emotional charge which kind of ricochets down to the present day.”

Nevertheless, Rob emphasises that what is shown in the film is not just a gathering of existing knowledge: “We did not just parachute into these villages, shoot our footage and depart. There is a lot of original research in the film, and what you see is the result of several years of work, and a collaborative relationship with the Nigeriens themselves.” He himself made three preliminary trips to Niger, travelling up and down the highway, listening to stories and correlating them with his own body of knowledge. “The memories of these events are still very much alive, but each community or family only has one part of the whole picture. What we could do was help fill in the gaps.”

For instance, Rob visited the French Archives Nationale d’Outre-Mer in Aix-en-Provence [/] where the official documents relating to the Voulet campaign, including the diary of Colonel Klobb, are held. It is impossible for the Nigeriens to access this due to problems of money and visas. But he was able to share his findings with the communities, and this, in turn, elicited more detailed information. “Our interest in the story, and the fact that we kept going back, had a catalytic effect and triggered more dredging up of memories.”

School children listen to the story of Voulet’s campaign in the village school. Photograph © LemKino Pictures / Inside Out Films

Starting the Healing Process

.

I comment that the whole project seems to have been a real educational process on both sides. “Yes”, says Rob. “And I hope that it will continue. I am of course delighted that the film has been so well received here in the UK. But I am actually more interested in how it will be received in Africa. We are planning, when the situation allows, to make another journey to show it in the communities who participated and use it as a starting point for discussions.

“Femi and I are of course Europeans, but all the other people working on the film – the guides, the interpreters, the film crew – were African. All of them were learning about their own history from a perspective which had not been taught to them at school. The thing about a film is that it concentrates experience, and focuses on a single issue, so I think people will be surprised by what is in it.

“And not only in Niger; I have been talking to people at the Hausa Language division at the BBC…” – this is because the film will be shown on UK TV later in the year –“… and found that they did not know anything about these events.” Hausa is spoken by about 80 million people in West Africa – in Nigeria, Benin, Chad, Ghana, Senegal, Sudan – and so the potential for education is enormous.

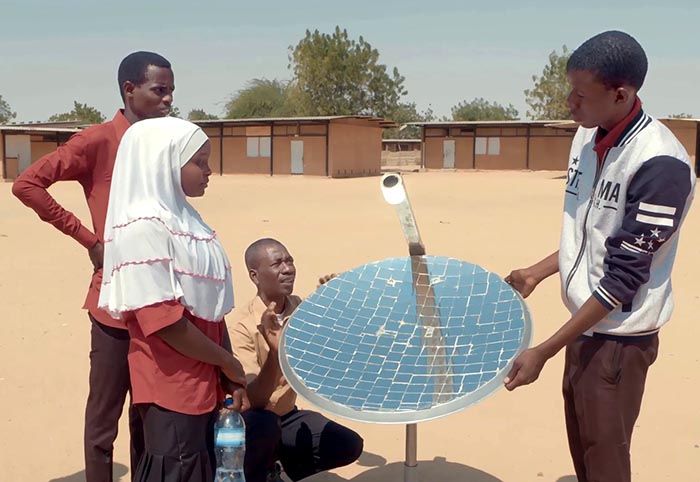

In the film we can see some of the possible results in Niger of this new knowledge, as children at a village school – many of them descendants of victims – are taught the history by their school master. They ask: “Will France pay for what they did in Niger?” This may be an early, tangible fruit of the film as, armed with new evidence, some Nigeriens are now debating whether they can bring a lawsuit for reparation against France.

But it seems to me that the matter of compensation is not the first consideration. The most important thing is that the true story is heard. I am reminded of the article we ran in the magazine on the new National Museum for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, which commemorates the 4000 or so Black Americans who died in the mass lynchings of the 19th/20th centuries. There, too, the first aim has been simply to name, remember and honour, people’s experiences.

Femi agrees: “The first step in any reparation is an acknowledgement of what has happened – the reality of what happened. There can never be proper compensation for the lives taken or the women violated, but we can listen to the story of what was done. Only then can we get over the denialism still prevalent in Europe, which is one of the major stumbling blocks to any kind of justice.

“And admitting that it happened means admitting that this was not just something that occurred in a faraway place. These events – not just in Niger but in all subjugated countries – formed the modern world. The wealth that the West has today came from this kind of colonialism.”

School teacher Omar shows his pupils how to set up a solar cell to power batteries which they can use for studying by in the evenings. Photograph © LemKino Pictures / Inside Out Films

Escaping the Lion’s Jaw

.

So if this is the first step, what comes next if we want to arrive at a position of social justice? As it does seem that this is what we need to do now; there is a growing recognition that we will not be able to move forward as a human race until we have acknowledged the wrongs done to certain sections of humanity and addressed them.

“There is an African saying,” Femi replies, “that the antelope will not start to heal until it is freed from the lion’s jaw. And you can say, conversely, that the lion cannot apologise or make reparation until it removes its jaw from the antelope’s leg. So, Europe really needs to stop exploiting Africa, as it continues to do today, whether it is resource exploitation of petroleum and uranium or the repayment of so-called debt.”

A particular ‘lion’s jaw’ that is wrapped around Niger’s leg is France’s continued mining of uranium in Northern Niger. Rob explains that when Niger was granted independence in 1960, it had to sign a defence treaty which stated that the national security of France would continue to be a priority for the new nation, and in return France would undertake to help them if occasion arose. This was common practice, and Britain included similar clauses in its independence agreements. But it has meant that until very recently Niger has not had any choice about the terms on which it supplies uranium – one of its few natural resources – to France. The French national grid relies almost entirely upon nuclear power, and about 30 per cent of its uranium comes from Niger. But Niger itself does not benefit substantially from the trade: only about 10 per cent of the population have electricity themselves, for instance, and this figure reduces to about one per cent in rural areas.

What is more, the film reveals that the miners were not told of the dangers of their occupation, nor were they provided with proper equipment to ensure their safety. We hear ex-miners talking about their experiences of working without protective clothing, and about their colleagues who have suffered illness and death due to their exposure to radioactivity.

But there are some areas of hope. Niger has been a pioneer in the production of solar energy, exploiting the almost continuous sunshine in these sub-Saharan regions. The world’s first solar-powered machine – a thermo-nuclear pump – was actually developed by Nigerien scientist Abdou Moumouni Dioffo in the 1960s, but his schemes never got off the ground because international investors at the time were more interested in uranium mining. Now the programme is being revived. Some of the most delightful sequences in the film show school children learning how to set up simple solar panels to charge batteries so that they have light to study by at night, and being introduced to ideas of self-determination and self-reliance. (For more, click here [/].)

Nigerien guides Amine Weira and Assan Ag Midal Boubacar talk to Femi about his reaction to the stories they have heard. Photograph © LemKino Pictures / Inside Out Films

A Personal Journey

.

But African Apocalypse is not only about Voulet’s fateful journey. It is also the story of the journey that Femi made as a black Britain returning to the land of his forefathers. It begins in Oxford, where Femi, a native of Manchester, was a student at the university and participated in the campaign to have the statue of Cecil Rhodes – a notorious slave trader – removed from the High Street. It ends with him returning from Niger in the summer of 2020 to find the UK exploding with ‘Black Lives Matter’ protests and a new awareness of British colonial history.

I ask him what impact the experience had upon him personally; for instance, in the film, when he first arrives in Niger he remarks that this was the first time he found himself in an environment where everyone looked like him. “Yes, it was my first ever extended journey in Africa, and it was as much a journey of personal development as it was about the film. It was about connecting to my own history and the history of my family, who came from Nigeria. I also learnt a huge amount about Africa and about African culture. I even learnt a bit of Hausa.

“But most of all I learnt about humility. Just because you have read some books at Oxford about colonialism and participated in some action, it does not make you an authority on colonial history more than the people who have actually experienced it. Usually in history you are reading a source which is several degrees removed from an event, and it is like a great game of Chinese whispers: a story is taken from someone who heard something, who heard it from someone else, etc. But the people we met are only two or three whispers away from the original, so I learnt a lot about the actual brutality of colonialism from the horse’s mouth.”

But although he clearly got on well with the Nigeriens, it was not all plain sailing. At one point in the film, Femi is confronted by the guides – Amine Weira and Assan Ag Midal Boubacar – about his seeming lack of emotional response to the terrible stories he was hearing, which they found very different from their own reactions. Was this a surprise to him? “Well, yes, it was. I learnt a lot about myself and about how in many ways my relationships and my mannerisms are very Europeanised. Although I am black, I am also British and I have led a very privileged life compared to these people. So, this really has been just the start of a journey for me – the journey of decolonising myself.”

The film also shows him taking an interest in the spiritual customs of the Nigerien villagers. Was this also the start of something? “I am not a deeply religious person, but in terms of spirituality, I think Africa has very much been robbed of its spirituality and had external religions imposed upon it – not only Christianity, also Islam. So, meeting and learning about the native customs of the people, learning about their understanding of the spirits in the landscape and what these spirits mean to them, was a very interesting and illuminating experience for me. Their retention of these beliefs has been, in itself, a kind of resistance to colonialism, I feel.”

Bristol, UK, 7 June 2020. ‘Black Lives Matter’ protesters pull down the statue of Edward Colston, who made his fortune in the slave trade, from its plinth in the town centre. This was the culmination of a long campaign to have the statue removed. Photograph: Mark Simmons

Contributing to the Debate

.

Finally, I ask about how people can see the film, as I understand that it will not be distributed in the normal way through cinemas. Rob tells me that it is available for rental on the British Film Institute Player [/] and will also be shown on UK terrestrial television later this year (2021). But although the film is expected to have a long and active release at festivals and on television around the world, the main form of distribution will be through showings by community groups and conferences where it can act as a starting point for discussion. “There will be a lot of showings at universities in the next few months. There is huge a degree of interest now in these things.” To support this educational aspect, the film’s website [/] includes a wealth of ancillary material which draws on the background research that Rob and Femi did.

Given the huge surge of interest in the history of empire and slavery which has arisen in the last year, the timing of the film could hardly have been better. This is remarkable given that Rob actually started work on the project as long ago as 2014. “Yes. We were actually a bit late in delivering the film – it should have been ready six months earlier. But had it come out in March/April, it might have been seen as being a bit ahead of the curve. But things have moved along so quickly since the death of George Floyd in the USA last May that the issues that it raises have suddenly become mainstream. So we are very excited – and hopeful – about what will come out of it.”

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Villager elders show Femi and his African guide Amina the burial places of their ancestors who were killed during Voulet’s campaign. Photograph © LemKino Pictures / Inside Out Films

First inset: Femi Nylander. Photograph © LemKino Pictures / Inside Out Films

Second inset: Map of West Africa. The route Voulet took now forms the border between Niger and Nigeria.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] JOSEPH CONRAD, The Heart of Darkness (first published in Blackwoods Magazine, 1899).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

A visit to a new memorial which aims to heal a dark period of American history

Reconciliation and Justice in Australia

How a nation is trying to heal the wounds of its colonial past and reconcile with its indigenous people

The Revival of the Commons

Political strategist David Bollier explains how a new economic/cultural paradigm is challenging the increasing ‘enclosure’ of wealth and human creativity

The Universal Language of Football

Kawther Luay on how the Homeless World Cup is giving hope to thousands of people all over the world, and talks to its co-founder Mel Young

READERS’ COMMENTS

To find out more about the film and showings, see

To find out more about the film and showings, see

To be shown on BBC 2 later in 2021

Timely and dispassionate, two necessities of Truth-telling… In hope of moving the conversation/education along post BLM etc…If we don’t know how we got here we cannot deal with what is even more necessary for our future…

From Benin Koni to Bablock Hythe

Paul, Paul

why did you do this to me?

Take your column of troops

& artillery

& smash your way into the

heart of Africa

leaving a swathe of carnage ,

unaccountable corpses

& unimaginable suffering

in your wake.

Did you fell the cream of Africa

Like the forest trees

Scattered upon the desolate plain?

Benin Koni, the capital of a continent,

built by generation upon generation,

wasted.

Paul, Paul

You knew what you were doing,

this terrible deed

while it was happening.

Why did you depart from your original nature

so?

Have the ants eaten your soul as they have

consumed your body?

But there was nothing left there

to bring life to the land

only more death.

Paul, Paul

Where are you now?

Lost, alone, wandering the land

of your suffering

looking for your lost self.

How will you find it, Paul?

That burnished splendour, your original nature

that your mother saw –

as did all the mothers whose children were

slaughtered by your hand.

Have they forgiven you, Paul?

Have they forgiven you?

Not until you have addressed

each and every one and asked

forgiveness.

That is the hardest path now, Paul

But if you can, and

if you do

forgiveness can come

& resurrect those glorious souls and your own,

free from the stench of battle,

free from the memories of those who came after

& the indelible stain of blood by the highway

& then the Road, Paul

then the Road

that drove you to your madness in the

Heart of Darkness.

A road that devoured the lives of those who came after

& fed your homeland with its yellow cake

to warm its hearths

but leaving the heart of Africa without even

light.

New light can come in this world through

timeless justice being served and

reparations made

Maybe not for the gore of ages that we all share

& shame in

But for the continued agonies of the present

that were born then.

Light can come

& hope spring up &

banish the fear that reduced the

noble spirits &

laid generations

low.

Hope can even come to you,

Paul

& lead you from your darkness to

return to the original light of

being itself.

And on my boat in Bablock Hythe

I too can find solace

in the knowledge that

all that can be done, has been done

& humanity, mine and yours, Paul

can move on in peace.

Richard Twinch, Oxford 26 April 2021