Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 19, 2021

The Heritage of Afghanistan

Robert Darr reflects on his long relationship with the people and culture of this ancient land, and shares his insights into its present situation

The Heritage of Afghanistan

Robert Darr reflects on his long relationship with the people and culture of this ancient land, and shares his insights into its present situation

Robert Abdul Hayy Darr is a writer, translator and boat builder who lives in the San Francisco Bay Area in California. He is also the director of the Afghan Cultural Assistance Foundation which for more than thirty years has been helping Afghan refugees adapt to life in new homelands. In the late 1980s, he worked for the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) delivering famine relief in eastern Afghanistan, and recorded his experiences in his book The Spy of the Heart.[1] He is a long-time lover of Afghani–Persian culture who has translated several works of Persian poetry into English,[2] and a follower of the Sufi tradition, a student of the Afghan master Raz Mohammad Zaray and of the teachings of Ibn ʿArabi. In this conversation with Jane Clark and Richard Twinch, he talks about the great cultural heritage of Afghanistan, and gives us some insight into recent events.

Jane: Can we start by asking you about how you originally became involved with Afghanistan and Afghan people?

Jane: Can we start by asking you about how you originally became involved with Afghanistan and Afghan people?

Robert: It happened many years ago in about 1983 or ’84, when I met some Afghan immigrants at the flea market in Sausalito. The first person I met was a man called Rahim Akbar, who had had a Fulbright scholarship as a young man and left Afghanistan. His family settled in California, and I would go and look at the beautiful carpets and things that he was selling. And I just became curious about these people. Like many of us, I had been reading the Persian literature that was coming into English translation at that time – ʿAttar’s The Conference of the Birds,[3] and the poetry of Jalal al-din Rumi, and so on – and I thought: my goodness, here’s someone from this country that seems so magical, mysterious and interesting.

There were some members of Rahim’s family who were involved with Sufi practice, but he was not. He was a modern person, but very nice. All of them had the most wonderful personalities and characters, and I was immediately drawn to them. They reminded me of my childhood; I am from Tahiti and when I was young I was part of that kind of tribal culture. They immediately embraced me as a friend, and I would go over to their home, and so on. And so it all started there.

Richard: So they were part of the first wave of immigrants who left Afghanistan after the Soviet invasion in 1979?

Robert: Yes. There were already problems in 1984, and in fact even in the late ’70s, if you could get out, you certainly would.

Jane: You started to learn Persian at this time, I believe.

Robert: Yes, I started by just sitting with Rahim and his family at their homes and trying to learn a few words, and they would be delighted to teach me. Through them I met other Afghans and some Persian people, of which we have quite a number in Marin County. Then the local authorities in Hayward and Fremont began calling me to deal with some Afghans who had landed in jail. The issue was that they would use corporal punishment on their kids and hit them if they were cheating or stealing. The police, of course, would come to the door after talking to their teacher, and say: well, you can’t do that here. It’s inconceivable to someone from that culture that you could not discipline your child in their best interest, so it was a tough situation.

It started with one case, and then pretty soon I was getting regular calls about all sorts of things. And that was the first time that I was formally involved with the Afghans. It was a fluky thing, because I was just a carpenter, a boat builder, but I befriended them and I got a reputation for being able to straighten things out for them.

Jane: So how did you help these people who insisted on disciplining their children?

Robert: What I said was: listen, if you wish to discipline your child in this way, you would be more likely to get away with it in Turkey. If you like, we can help you move to a Muslim country. But of course, none of them wanted to go to Turkey. So then they would be faced with the alternative of coming into compliance with our laws.

Some of the problems were very, very severe; I have mentioned a relatively mild one. But in all cases, the issues had to do with people coming to terms with what they had lost, which was their homeland. There were lots of emotions, lots of sadness and lots of difficulties. I am now working, through the Afghan Cultural Assistance Foundation, with the new refugees who have just been evacuated. It’s not just a question of moving to another country: people have lost their cause and their country is being destroyed. Maybe their relatives have been killed or imprisoned and tortured. So people bring a lot with them that needs attention. There has to be psychological counselling, and there has to be cultural help in getting them settled and adapted into this culture of ours.

Going to Afghanistan

.

Jane: The Foundation has been going for a long time now – since 1985 – so it has been helping refugees for nearly forty years. How did you come to set it up?

Robert: I think it is important to say first that I have always thought of my relationship to Afghanistan and the Afghan people as a ‘swinging door’. It’s true that the main aim of the Foundation is to help Afghan refugees adapt to our culture; but we also get a bunch of culture and insights and wisdom back from them.

It all came about in a strange way because of a conversation with Amina Shah, Idris Shah’s oldest sister. I met her in London in 1985, very soon after meeting these Afghans in the United States. Hearing that I was on my way to Greece for a vacation, she asked me whether I would mind going to Turkey on the way to talk to some Afghan refugees who had settled there. I instantly agreed, having no idea how difficult it was going to be. In fact, I never got to Greece because it took me so long to find these people, and I was stopped by the authorities for trying to look into matters that should not concern foreigners, etc., etc. But I found them eventually in central Turkey and befriended them using my basic language skills. There was one guy who spoke a little English, called Mohammed Sharif, and as I was leaving, he handed me some extremely finely woven silk rugs, and said: “Please take these and sell them, and send us the money.” So I did.

It was remarkable because they had only known me for a few days. But my life completely changed and moved in a different direction because of that encounter. They were northerners, largely Turkmen people – carpet weavers who were very good at what they did, but they had no market in Turkey. So that is why the Afghan Cultural Assistance Foundation began – in order to help them.

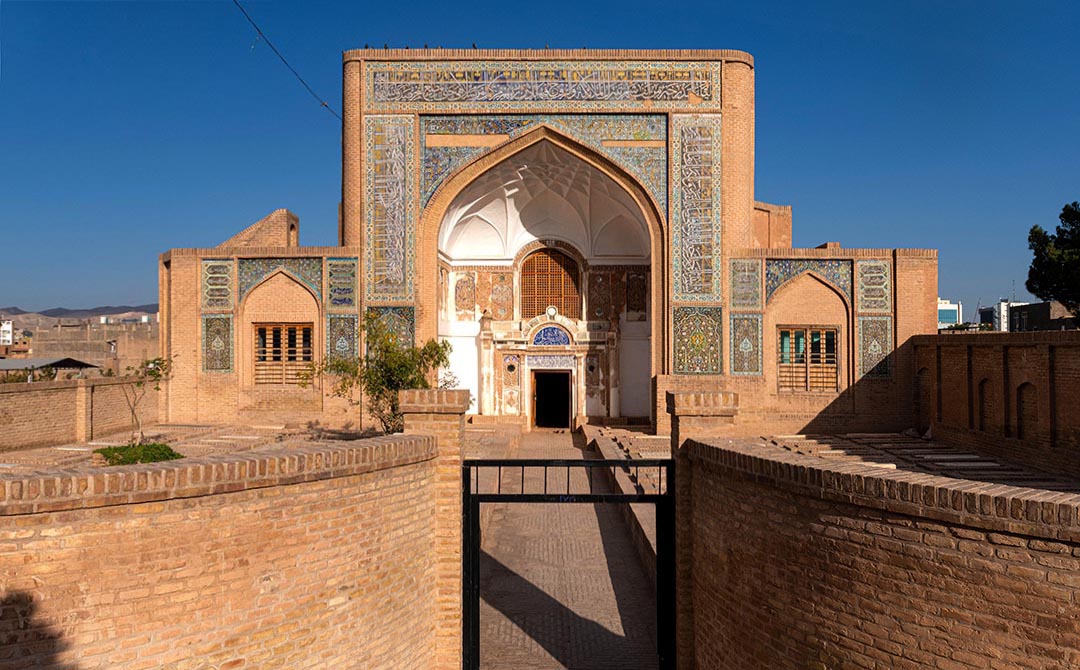

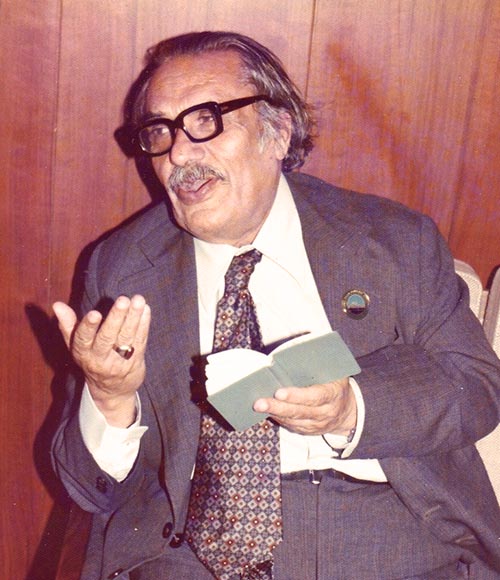

Robert discussing carpet designs in the Sawabi refugee camp near Peshawar, Pakistan. In 1987 the Afghan Cultural Assistance Foundation set up its own carpet-weaving project, funded by the United Nations, so that refugees could make a living. Photograph: Courtesy Robert Darr

Jane: So this eventually led you to Afghanistan?

Robert: Well, what happened next was that someone at the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR) called me one day at my boat building school in San Rafael [/] and said: “I want to talk to you about your project in Turkey”. And I said, “We have no project in Turkey. We just have this relationship with a group of refugees, selling their rugs.” Then he said, “Well listen, Robert, I’ve spoken to those refugees and they are very happy with your organisation. Would you consider going to Islamabad in Pakistan to help us figure out what could be done there?”

And I said: “No. I’m the director of a school and I’m busy.” But then my school burned down. Burnt to the ground! My dog died of smoke inhalation and my insurance turned out to be insufficient, so I had to sell everything to pay my workers and provide for my family. So when he called to ask me again I said, “Yes”.

I spent some years coordinating support from Islamabad, and then soon afterwards – in about 1989 – the UNHCR sent me into Afghanistan. I went into Kunar Province and found the Wahhabis there. That was the first time I knew that there were foreigners who were bringing the fight against what they called ‘stray Islam’ into Afghanistan. They were killing locals who did things like praying the wrong way. So this was my first encounter with those emerging forces that were to become the Taliban. The Taliban did not really exist until 1994 and they only came to prominence in the late 1990s. And of course, 9/11 did not happen until some years later.

Then soon after that I got involved in famine relief. I was made director of the North Central Region, in charge of distributing wheat. And that’s when I became extremely involved with things inside Afghanistan.

Richard: This was during the Soviet occupation of course, when the Afghans were resisting foreign rule. And it was this period, when you were travelling across the country taking provisions to people in the villages, that you wrote about in Spy of the Heart.[1] But your work within the country only lasted a short time, I believe?

Robert: I had to leave in 1990 because of getting into trouble with the Pakistani authorities through newspaper interviews, and I really could not work in the region anymore. And also, by then I had post-traumatic stress disorder from being in a war zone. I was not a combatant, but you don’t need to be a combatant to get into trouble when people are being killed all around you and you’re seeing lots of death and destruction. So I realised that it was time to get out.

But of course, I have kept in touch with people in Afghanistan and have continued my work with the Cultural Assistance Foundation. So when 9/11 happened in 2001, I was very much in touch with Afghan people because I was working with them. So I knew something that maybe a lot of people didn’t know, which is that one month earlier, the then-leader of the government, Aḥmad Shah Massoud [/] – the famous military commander who fought against the Taliban – had strongly warned the United States when he was in Paris that there were plans for a devastating attack against them. He had apparently gained information about this through his own spy networks. But he was not listened to.

Pashtun man in the Karkhanai Bazaar, Peshawar, Pakistan, 2019. Photograph: MSelcukOner /iStock

The Pashtuns and Pashtunwali

.

Richard: Given your long experience of the country and its people, what would you say about what is happening now?

Robert: What you have to understand about Afghanistan is that everything is about ethnicity. And the largest ethnic group – two or three hundred tribes – which make up about fifty per cent of the population, are the Pashtun people who live in the south-west of the country. There are also Pashtuns in north Pakistan: they are the second largest ethnic group there, making up about fifteen per cent of the population. The whole area is often called ‘Pashtunistan’ because they are really one people bound together by very strong ties, and the border between the two countries – called the Durand Line – is very artificial from their point of view. The group spills over both sides of it and in many ways they behave as if it does not exist. A lot of what’s going on today can be explained by this, especially the relationship between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Map of ‘Pashtunistan’

The Pashtun are an amazing people. They have been in the area for millennia and have constantly been engaged in struggles: with the Greeks, with the Iranians, with the English, with everyone, over and over. You can read about them in Herodotus and see that they are the same people now as they were then. And they have the same strategy; they watch while you enter the country and then they attack you once you’re trapped inside.

They have had to survive so many invasions that they have developed a very rigid moral code called ‘Pashtunwali’, which goes way back before the coming of Islam. Pashtunwali has very strong values – one of which is that women have to be very carefully watched and held in a certain relationship to the tribe and family, in such a way that there are no scandals. People think that these ideas have come from Islamic culture, and this is to some extent true, but within the context of Pashtunwali the restrictions upon women’s freedom are more severe even than the most literalist Islam.

Another value is a very fierce resistance to occupation by any foreign power. So they don’t want any foreigners taking over their country, and they definitely don’t want anyone telling them how they should treat their women. And this has been a big problem because in the last twenty years it has not just been Persian-speaking women who have become more free, but many of the Pashtun women have also been finding a new degree of freedom – and very much enjoying it.

Richard: I understand that there is also a very rigorous code of honour.

Robert: Yes, Pashtuwali has some very noble values, such as giving refuge to an enemy. When I was delivering famine relief, we had to go through Pashtun territory, and it was dangerous because people were getting robbed all the time. One of the Afghans said to me: “There’s a way around this; you must go and meet with the leader of the next tribe and ask for their protection.” So I did, and it was the funniest thing: those same people who might have robbed us were diligent – absolutely diligent – in giving us protection because we asked them for it. That’s Pashtunwali. And that’s why Bin Laden was harboured in Pashtun territory on the Pakistani side. They said: he sought refuge from us, so we can’t just give him up; that would be contrary to our culture.

But there are other things which are less noble – retaliation and vengeance are high on the list. If someone is killed, it is absolutely necessary that someone from the other tribe must be killed. Well, of course, that means that at some point you can’t figure out anymore who started it and there’s just endless killing. And if someone looks at a woman: well, they’ve crossed a red line, and that person, or the woman, will be harmed. Many of the issues I had to deal with in the San Francisco Bay Area had to do with this. The children were going to American schools, and some fathers became angry and, frankly, out of control – threatening to kill some boy at high school just because their daughter had said hello to them.

Jane: So how did they manage to integrate into the community in California?

Robert: Well, not everyone in Afghanistan is Pashtun, and the people who live in the cities and speak Persian are very different. I came to know a family in the Bay Area who had actually been at the Afghan court before the King was deposed in 1973. They told me that during the time of the King, they would get their clothes from Paris and their food from Europe, and women being educated was normal. There were even more women than men in medicine. Women at university would meet men and often they would try to get permission from their families to marry that person, rather than have an arranged marriage. Arranged marriage still happens in Afghanistan, by the way, especially in the countryside.

So, in the first wave of immigration in the 1970s and ’80s, the Afghan people who came to the US were mostly from the urban areas and they were used to that kind of culture. It was largely the people from the rural areas who had the problems in adjusting, especially the Pashtun because of their very rigid codes.

It is important to understand that the Taliban are basically a Pashtun movement. People try to tell me that they have become much more than that – that they have won because they have recruited people from other ethnic groups as well. But even if they have, they are still basically Pashtun and they have the values of Pashtunwali.

15th century miniature, Nezami Welcomes the Minister Nava’i, from ‘The Rampart of Alexander’ by Mīr ʿAli Sher Navāʾī (Herat, 1486), artist ‘Qāsem, son of ʾAli.’ Navāʾī, who was also a minister at the Timurid Court, is presented to Nizāmī (d. 1209) by his own master, Jamī (d.1492), in a magical garden among the shades of the greatest Persian poets. Image: Bodleian Library, Elliot, 339, f.95 verso. Courtesy of the Bodleian Library, Creative Commons Licence[/].

Run your mouse over the picture to zoom in on the details

Spiritual Heritage

.

Jane: I gather from what you are saying that there is a great cultural divide in the country between the people who live in the cities and the Pashtun who live in the countryside.

Robert: Yes – and actually, I have never learned to speak Pashtu. The reason is that it is considerably more difficult than Persian, and also, almost everyone in Afghanistan who lives in a town or a city – rather than a village – speaks Persian.

Richard: It’s called ‘Dari’ in Afghanistan I believe.

Robert: Yes, Dari is a particular dialect of Persian, but if you speak Farsi, which is the Persian spoken in Iran, it is very easy to understand Dari, and vice versa: it is kind of like an American talking to an Australian. The great attraction of Dari is that the literature in Persian, and in the old Persian language, is immense. It is as great, or even greater, than all of European literature put together. There is an astonishing amount of material, and most people in Afghanistan would have either read some of it, or they would have sat next to someone who could read it so they could memorise it.

Jane: When you read histories of the Islamic world, you come across mention of this region called ‘Khorasan’ where so many important things happened, but most of us now are rather vague about where it actually was. But Khorasan was basically Afghanistan plus parts of Eastern Iran, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, and it included great centres of learning such as Nishapur, Herat, Bukhara and Samarkand. Rumi and ʿAttar came from there, as well as Jami and Omar Khayyam.

And it has also been an important place for Sufism, the home of people like Bayazid al-Bastami and al-Hallaj, and then later, Bahauddin Naqshband who founded the Naqshbandi order. You became very involved with the Sufi tradition when you were working there, and continue to be so. How did it all start?

Robert: Well, the first thing was that I had the privilege of meeting Ustad Khalilullah Khalili [/], who was the last of the great court poets of Afghanistan. He had been poet laureate before the Russians invaded. I met him through reading Rumi and ʿAttar, because I came into contact with Octagon Press who had done a translation of his work.[4] So when I arrived in Islamabad in 1986 I had already memorised some of his quatrains – literally, because I had the habit of memorising stuff from my Tahitian education – and with a group of American friends we had been translating them because we found the Octagon translations a bit stiff.

I was the main translator, but I wanted help because I was a carpenter, not really a writer, so when I got to Islamabad and heard that Ustad Khalili was living there in exile, I went to see him. It was an extraordinary meeting because at that stage my spoken Persian was not very good; he would say something and I did not have the skill to reply, so I simply quoted some of his verses to him. So of course we instantly became great friends! Even though I only met with him on a few occasions, he made a very, very profound impact on me.[5]

Khalilullah Khalili. Photograph: rumibalkhi.com

And by the way, I am now translating the poetry of his son, Massoud Khalili [/] as of nine months ago. I’ve now translated about 100 quatrains and they are going to be published before long.

Massoud Khalili was a close friend of Ahmad Shah Massoud, and he was seriously wounded when Ahmad Shah was killed in 2001. This happened, as you may recall, about two days prior to 9/11, when he was attacked by the Arab fanatics who were working with the Taliban. Ahmad Shah Massoud was Muslim, of course, but he was much more moderate than the Taliban: he was also a Sufi, and his regime promoted democracy and human rights, including the rights of women.

Massoud Khalili subsequently spent about two years in hospital because he was so badly injured. He and I are about the same age, and I had met him when I went to see his father in my early thirties. So when he asked me to translate his poetry, I said fine. I didn’t realise it was going to be so much work, but it’s been an absolute delight.

A woman weaves a silk carpet with the Afghan royal pattern and 80 knots per centimetre at the Samarkand-Bukhara Silk Carpets workshop, Samarkand, Uzbekistan. Photograph: Oleksandr Rupeta [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

Three Diasporas

.

Richard: It seems to me that over the past fifty years Afghanistan has been experiencing a series of diasporas. The first one was in the 1970s and ’80s, after the King was deposed and the Soviets invaded; there was another when the Taliban took control for the first time in 1994; and now we are seeing a third one as they come into power again. Do you think that you can liken these to other diasporas – such as happened in Tibet when the Chinese went in? In that case, the effect has been to spread the culture beyond the country, and we have all been enriched by it.

Robert: Well, this is exactly what happened the first time around when the people coming out were the inheritors of traditional Afghan–Persian culture. For instance, among the people I met in California was the last living court librarian and painter, Homayon Etemadi, who was the cousin of Zahir Shah. He came to live in Alameda with his wife and they had an apartment there in the Bay Area.

I signed up with Homayon for painting classes as a ruse to get to know him, and I succeeded and became a close friend and student of his for more than twenty years. He was the inheritor of a continuous tradition of miniature painting which went back to the great Behzad [/] in the 16th century. I had his work up at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, down in Monterey, and I started up classes with him in Oakland so Westerners could come and study with him. He was also a Sufi – one of the last examples of authentic classical culture.

Jane: Could you say something about his Sufism?

Robert: Well, he would never pray in a mosque; he always prayed privately. And he was extremely rigorous in his practice: in fasting, for example. But at the same time he was so open-minded. He told me that there is a Sufism that’s based entirely on beauty and art – it is its own path, and its practices are all about creating beauty.

One day I asked him what he thought about Western art, and he replied that all art, if it’s genuine, is spiritual – and therefore all of it is redemptive and transformative. So I asked: “Is there any higher or lower?” and his answer was: “Well, yes. The less you’re in it, probably the better will be the meaning” – meaning that the more detached you are and engaged in its spirit, the more profound the work of art will be.

But he didn’t put down Western art, or any art. He said that all art was part of the Sufi way. He had a sort of universalist perspective, and that it is the kind of thing that has now been lost in Afghanistan. You could say that it was already going away just with the passage of time. But what we have seen over the last thirty years is what happens when you really lose those treasures: when violence comes to your country and these precious people flee and benefit another culture.

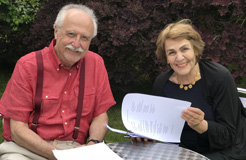

Robert with the miniature painter, Homayon Etemadi. Photograph: Courtesy Robert Darr

Richard: So what about the people coming out now? Are we going to see a further transmission of wisdom?

Robert: What is happening now is different because, I am sorry to say it, but the classical culture was actually on its way out in the first diaspora. A lot of what’s been going on in the last 20 years is about the Afghan people understanding the wider world and participating in it: in contemporary arts like film and theatre and dance, in athletics, in science and technology, and so on. It’s not been so much about traditional culture. (For an exception to this, see this video [/] about Fahima Miraei, the country’s only woman practicing Mevlevi turning.) There is a scholar called Michael Barry who works with the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and specialises in miniatures painting.

Jane: I am familiar with his work through the wonderful illustrated version of Canticle of the Birds.[6]

Robert: He has spent the last two decades of his life trying to reintroduce Afghans to their own culture through miniature painting. But really, the preservation of this tradition is now outside the country, where all the big museums in USA and Europe have remnants of the beautiful miniatures that were painted in the classical period. And it is the same with the heritage of Homayon. We managed to persuade him to pass on the secrets of his paint mixing and his gilding, which normally he would not confide to anyone except through a very special line of inheritance; so some of his western students have become very good miniature painters using the classical techniques.

We westerners often want to try to preserve things when we see that they are precious. Another example is the work of Jane Lewisohn who has a project to preserve the musical heritage of the Iranian period which would otherwise have been lost (click here [/] to learn more).

The new generation in Afghanistan – those who are fleeing now – don’t know what they once had. And I find myself in the ironic situation of telling them about it because I have studied with the older people. I would say that these things are in the soil of Afghanistan, but most of the roots have withered now and the Taliban are not going to concern themselves with reviving them. They are traditionalists, but what they are concerned with are mostly moribund notions of religion and spirituality. One of the great art forms of Afghanistan has always been music. There is a long, long tradition of both classical and folk music, and the people love it; there is music and poetry on the radio day and night. (For example of traditional Afghan music see video right or below). But the Taliban are already banning the playing of musical instruments, and closing down the radio stations.

Video: Afghani Rabab: Valley Song. Duration: 3.03

Members of the Young Afghan Traditional Ensemble, in Kabul in 2013, playing the Afghan instrument, the rabab. To hear their performance, click here [/]

The Hope of Beauty

.

Jane: There are many other aspects of your life and work that we don’t have time to go into today. One of these is your continuing contact with Sufism, particularly the group founded by Raz Mohammad Zaray [/] But I just want to ask you about the many people attached to the Sufi path who remain in Afghanistan. What do you think will happen to them? Are they in danger, do you think?

Robert: I am afraid that inevitably they will be. The Taliban may allow one kind of Sufism – the sort that goes back to the Deobandi period in India during British rule, which is essentially just Islamic practice. But that doesn’t have the freedom of other types of Sufism, like that of the Naqshbandi Orders, or the teachings of Ibn ʿArabi which I am involved in. The present group may say that they are more liberal than the previous rulers, but they have nevertheless embraced a notion of jihad (holy war) which is about supremacy and violence instead of self-work.

Richard: So can you find any cause for hope in the present situation?

Robert: Well, the Taliban are certainly going to clamp down on dissent, and kill anyone who disagrees with their understanding of Islam. But there’s one troublemaker in their culture that they cannot do anything about – and that is Hafiz. I mean the 15th century poet. The Afghans are very, very appreciative of Hafiz – and of his fellow poets like Rumi, Nizami and Saʿdi. As we mentioned earlier, the most dominant tribal group in Afghanistan are the Pashtun people who, for the most part, speak Pashtu amongst themselves. But most of them will also know some Persian, and be familiar with – and love – a great deal of the Persian poetry. And literature really speaks to people: it is very hard to snuff out its effect. No matter how powerful you are, there is nothing you can do to counteract the effect of beauty.

So I think that hope lies in poetry – and in music. I have studied Afghan music and a lot of it is written in Pashtu; there are some beautiful Pashtu songs. (For an example, see the video right of below.) So I feel that the Taliban ultimately can’t succeed because the Afghan people are too strongly rooted in their music and poetry. And over time these are extremely powerful forces that can dissolve or get through the lines which divide people – and soften them. These poems do not stress nationalism, but the opposite. They speak of universal values which transcend borders. So the Taliban can shut down the radio stations, but they cannot stop people listening to what is coming out of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, which are just across the border.

Video: Pashtu Song by the 19th century master, Hamza Baba.Duration: 5:36

This softening process may take a long time, I am afraid. We seem to be living in times when many people – maybe because of fear or lack, in our countries as well as in Afghanistan – are becoming more conservative. The only thing that can counter this tendency are displays of beauty – in literature, in art, in music – and we just have to do what we can whilst we wait for the storm to pass. On my part, when the Foundation helps people out of Afghanistan these days, we try not to bring them to the USA or Europe, but rather to settle them in places like Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, where they can have a decent life while they wait things out.

Jane: I think it is a wonderful point at which to stop our conversation, affirming the power of beauty and our trust that its eternal quality will change things in the end.

Robert: It is the best that human beings have ever been able to do. Think of Diotima, who says to Socrates in The Symposium: love is not a god, beauty is god – and when it departs into the formal world, love is in sorrow and follows after it. So the principle of spirit is beauty, and the Afghans have incorporated this in their poetry: for them, beauty is the only redeeming principle because, as it says in the hadith literature: ‘God is beauty and He loves beauty’.

A Selection of Modern Afghan Poems

Quatrains by Khalilullah Khalili (1907–87)

If you hear the language of the stars

Overnight you’ll hear the secrets of the world.

Silence of the night will sing [a] hundred songs

In your ears, the stories of the skies.

Oh Great Mountain, reaching far into the sky!

How long will you find satisfaction in self love?

Though just a tiny butterfly, I am yet free,

To dance on a flower head while you remain shackled.

In every state the Heart is my refuge

In the realm of existence my sultan.

When I tire of the mind’s mischief

God knows I am grateful to my heart.

Light no candle at my grave

It could harm a frantic moth,

Nor grieve a loving gardener.

Don’t put flowers at my grave.

Fame-seekers more base than able

Have lent this world the face of hell.

How often blood stains the earth

As another nobody climbs to fame.

— — —

The Breakages by Massoud Khalili (b. 1950)

Seductive eyes might well break modesty’s looking glass;

The goblet, the cup, and the flasks of wine might also shatter.

Should you come, O fairy-faced one, with your arrow-glances,

they would destroy the noose, the snare and cage in desert and mountain.

If your steps should track through the temple and mosque in the dark of night,

they would break the puritan’s grip, the morality enforcer’s foot, and the mulla’s hand.

Head-cracking in the view of God’s lovers is the aim and wish of brave men;

for this reason Majnun with his head at Layla’s feet would have it broken.

Careful about the sighs of the oppressed who in the middle of the night

might well break the bonds and chains of injustice during many a midnight.

Do not be sad, O Beloved! Please do give a kiss from those lips!

For those sweet lips would break today’s and tomorrow’s sadness!

— — —

In the flames of Unity by Raz Mohammad Zaray (d. 2010)

I am a wine worshiper of that wine of Alast dawn,

sitting here in the corner of the tavern, just sitting.

With the comely Saqi, the all-conquering heart-embellisher,

freed from self, intellect, reason, and freed from all else!

He and I were there, but all was Him and none of me.

I closed all the doors to outsiders’ faces, closed them!

When the Beloved was of me and I was in His Face effaced,

I was wholly burned away, and I broke the goblet, broke it.

All of the created world is the vessel of that wine;

I drank all, then searched for wine and tavern, searched!

When every hair on my body cried out from His displays,

I saw that both the wine and the chalice were Me, were Me

O Zaray, boiling in the sparks and flames of Unity,

by the Beloved’s grace I’ve left the fantasies, left them!

There is a documentary film about Robert, Sailor, Sufi Spy, made last year, which is structured around his restoration of an old wooden sailboat. Click here [/].

—

There are also many talks and videos by given by him on the Sufi Garden website [/].

—

For his presentation ‘Waking to the Embrace’ at the 2015 Symposium of the Muhyiddin Ibn ʿArabi Society in Oxford, click here [/].

–

For the complete set of poems by Massoud Khalili, click here

Image Sources (click to close)

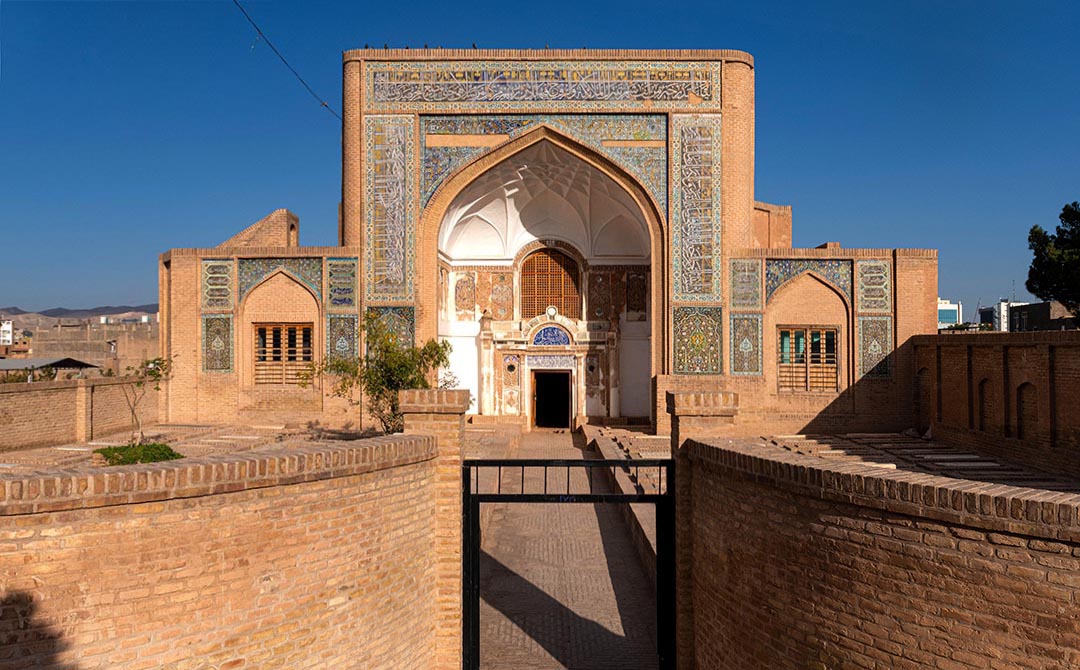

Banner: The tomb of the 15th century mystic and poet ʿAbd a-Raḥmān Jāmī (d. 1492) in Herat in 2019. Herat was the capital of the Timurid Empire and saw a great flourishing of poetry, painting, architecture and philosophy in the 14th–15th centuries, when it was known as ‘The Pearl of Khorasan’. Today it is the third largest city of Afghanistan with a population of about half a million people. Photograph: Michael Runkel/ robertharding / Alamy Stock Photo.

Inset: Robert Darr at his boat-building school, The Arques School of Traditional Boatbuilding [/], in Sausalito, California. Photograph: Richard Twinch.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] ROBERT DARR, The Spy of the Heart (Fons Vitae, 2006).

[2] ROBERT DARR:

Quatrains Khalili. (The Afghan Cultural Assistance Foundation, 1989).

Clarifications. Mystical Poetry of Rumi . (Real Impressions, 2002).

The Garden of Mystery. The Gulshani-i raz of Mahmud Shabistari. (Archetype, 2007).

[3] See for example, Farīd al-dīn ʿAttar, Conference of the Birds, translated by Dick Davies and Afkam Darbandi (Penguin, 1981).

[4] KHALILULLAH KHALILI, The Quatrains of Khalilullah Khalili, translated by A.H. Aljubouri (Octagon Press, 1969).

[5] For Robert’s translations, see ROBERT DARR, Quatrains Khalili. (The Afghan Cultural Assistance Foundation, 1989).

[6] FARID AL-DIN ʿATTAR, The Canticle of the Birds, illustrated through Persian and Islamic Art (Diane de Selliers, 2013).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Afghani Rabab: Valley Song. Duration: 3.03

Video: Pashtu Song by the 19th century master, Hamza Baba.Duration: 5:36

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Rumi: The Operation of Divine Love

Alan Williams tells us about his new translation of Rumi’s great epic poem, the Masnavi

Keith Critchlow: A Life Well Lived

Richard Twinch pays tribute to the teacher and sacred geometer who died on April 8th 2020

An Artisan of Beauty and Truth

An interview with artist and painter Etel Adnan on her early life in Lebanon and the influence of Sufism upon her work

Bewildered by Love and Longing

Michael Sells and Simone Fattal talk about a new translation of Ibn ‘Arabi’s famous cycle of love poems ‘The Translation of Desires’

READERS’ COMMENTS

I like this magazine but my English is no good. Love you

Very interesting about an interesting country I remember so well whilst there.

I am gutted (as is modern parlance) that I knew nothing of Jami and did not visit his Tomb whilst in Herat in 73.

next visit I will not be so remiss

An article of wisdom and compassion.

Thank you editors for the sensitivity of the conversation.

Thank you for this erudite, informative article and for celebrating the wisdom of Rumi and Hafiz.