Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 14, 2020

The Operation of Divine Love

Alan Williams tells us about his new translation of Rumi’s great epic poem, the Masnavi

The Operation of Divine Love

Alan Williams tells us about his new translation of Rumi’s great epic poem, the Masnavi

The 13th-century poet, Jelaloddin Rumi, has been a surprising best-seller in America and Europe for many years now, his message of divine love and mystical union finding universal appeal. His masterwork is the epic poem, The Masnavi, a monumental composition in Persian of some 25,000 verses – combining stories, fables and spiritual teachings – which is regarded by many within the Islamic world as its greatest mystical text. This month sees the publication of the first two volumes of a complete new translation into English by Alan Williams, Professor of Iranian Studies and Comparative Religion at the University of Manchester. [1] David Hornsby talks with him about the book and why he thinks it is so important for our contemporary world.

David: One of the people commenting on this new translation, Professor Ahmad Karimi Hakkak, has said that it is “intensely relevant not just to our time, but to all humanity through the millennia”. What would you say is the profound and universal message of the Masnavi?

David: One of the people commenting on this new translation, Professor Ahmad Karimi Hakkak, has said that it is “intensely relevant not just to our time, but to all humanity through the millennia”. What would you say is the profound and universal message of the Masnavi?

Alan: The main message is about the realisation of union with our true nature. But this cannot easily be put into intellectual terms, and that is why Rumi addresses the reader through poetry: poetry immediately addresses a different level from the literal, intellectual mind. The message is intended for the inner being or higher mind. To hear it, one has to be very patient and attentive.

Rumi went to great pains to explain what he meant in the best possible way, through ordinary language – that is, through stories and fables – but also by direct conversation with his readers, guiding them along the way. In my introduction to the first book, I talk about his way of leading the reader into a receptive state so that it is easier to understand what he has to say – to contemplate realities that are much subtler than we are normally used to reading in literature, even in other Persian, Sufi poetry.

David: For several years now, Rumi, particularly through the translations of Coleman Barks, has been one of the best-selling poets in the USA and Europe. This is extraordinary, considering that he lived nearly 800 years ago and in a very different culture. Can you say something about his life?

Alan: He was born in 1207 in an area east of modern Iran, in greater Khorasan (which means ‘the Land of the Sun’), the geographical area of ancient Bactria around Balkh in a region which is now shared by Afghanistan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. All these countries, as well as Turkey and Iran, now claim him as one of their national poets, although the area is not actually located in the territory of modern Iran. His family had to migrate when he was still a child, travelling 2,000 miles westward and settling eventually in Konya, now in central Turkey.

David: Do we know why they had to migrate?

Alan: This is actually disputed by scholars, but it is suggested that Rumi’s father, Bahaoddin Valad, may have been in dispute with his employers there and wished to leave. But the most likely underlying reason is the mass Mongol invasion that was on the horizon and which destroyed Samarkand a few years after Rumi’s family left. This was the invasion that came right into Asia Minor (modern Turkey), and in fact, many folk from Khorasan had gone before them and settled in Anatolia, driven by fear of annihilation. When Rumi began the Masnavi in the early 1260s the Abbasid caliphate had just been overthrown by the Mongol armies, who sacked Baghdad in 1258. Rumi probably did not know if his civilisation would survive – as we do not these days.

So these were very traumatic times for him and his family, and I think the signs are there in the Masnavi of a person who has been traumatised. There is the theme of deep spiritual nostalgia, which may have arisen from his own experience of being uprooted from his homeland and transported to a completely new environment in which he was a stranger. He was a young man when he grew up in Konya, not a child anymore, but his whole life was a catalogue of losses: loss of his homeland, loss of his mother and a succession of teachers, loss of his first wife Gowhar Khatun, not to mention the sudden disappearance of his spiritual guide Shamsoddin of Tabriz later on. All this was transformed and transmuted by Rumi in the Masnavi into a spiritual nostalgia that was cathartic and led him to the spiritual understanding for which he is famous.

Rumi’s mausoleum in Konya, Central Turkey, which is visited by more than two million visitors of many different faiths every year. The building houses the shrines of Rumi and his sons, plus the Mevlana Museum. Photograph via https://hulusiefendivakfi.org.tr/mevlana-turbesi-sebi-arus-mevlana-muzesi/

Spiritual Influences

.

David: What traditions influenced him? Was it the Zoroastrian tradition, the Islamic tradition, the Christian tradition? Konya seems to have been in a certain way at the heart of all of these.

Alan: This is true, Konya was one of the ancient centres of civilisation – the Iconium of the New Testament – and it was still so in the 13th century. Rumi was of course Muslim, and from within that tradition we have two main sets of influences. One was his background in Khorasan: he was profoundly influenced by the Sufi traditions of the region, which were different from those of the Middle East; and the other was the traditions in which he was educated and studied in Anatolia and Mesopotamia. These two traditions come together in Rumi; you can find both the quietest tradition associated with Junayd of Baghdad [/] and the more ecstatic tradition associated with Abu Yazid of Bistam [/].

People tend to focus on the profound influence of Shamsoddin al-Tabrizi [/] and his later teachers.[2] But his own father and his first teachers as a young man – when he was learning the Quran, and later studying the sciences of Islam – rooted him in his faith and in the spirituality of his father’s tradition of piety and homiletics (preaching sermons). Later, of course, we have his development into a Sufi of the more ecstatic kind with Shamsoddin. I have tried in my introduction to say something more about the nature of Shamsoddin’s influence on Rumi – both called one another Mowlāna, ‘Master’, ‘Lord’, out of respect.

I shan’t say anything here about the influence of Zoroastrianism, but I am aware of it as I read the language of his poetry. The Persian language he spoke is immensely ancient and rich in pre-Islamic nuances. To take one instance alone: for Rumi fire is not just the Muslim fire of punishment, but it is also the fire of love.

David: What about Christianity? There were still a great many Christians living in Konya during his lifetime, and Rumi is often thought of as being in a Christic saintly tradition in himself, developing the universality of that tradition in an Islamic context.

Alan: Certainly Jesus is, after Mohammed and Moses, the most mentioned of all the prophets in the Masnavi, and he is spoken of with great feeling, as is Mary his mother. And you could say that there is a very strong Christian theme in the Masnavi that God is Love, that Love is God.

However, Rumi is very anti-trinitarian and rejects the doctrine of incarnation. But that being said, part of his appeal to the West, I would say, is that he talks about the embodiment or presence, or possibility of presence, of the divine in the human heart. This is a very powerful teaching – that the human heart is capable of such depth, of such transcendent strength. Unlike many Islamic texts, he doesn’t use the word insan al-kāmil, ‘the perfected human being’, in the Masnavi, but he does talk about the ‘man of God’, and alludes to what Christian mystical theologians call theōsis – ‘becoming God’, ‘divinification’.

He doesn’t go as far as some mystics – such as Meister Eckhart [/] or Ibn al-ʿArabi [/] – to talk about the absolute Godhead and elevate the concept of the Perfect Human to a virtual doctrine, although this is debatable. What I would say on this subject is that for Rumi there is a universal presence in form, and that without form there would literally be nothing and no purpose in creation. There is also the idea that all is meaning, or spirit, but without form there would be no manifestation.

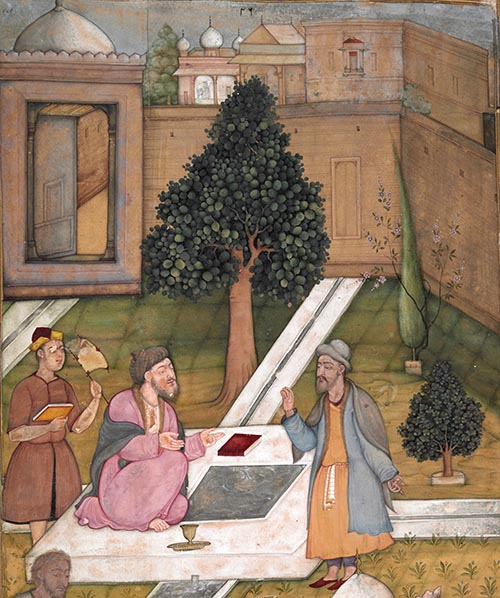

Rumi and ‘Attar, the two great masters of the masnavi form, are depicted as meeting in Nishapur in an illustration to Jami’s Nafahat al-Uns, Agra, India 1603. Image: © The British Library Board, Or 1362.f287r

The Masnavi

.

David: Turning to the Masnavi itself; can you say something about it and its importance?

Alan: Rumi began the Masnavi in the early 1260s, about ten years before he died in 1273. He had already written thousands of ghazals (love poems), robā’is (quatrains) and other short poems that make up the ‘collected poems’ which are popularly known as the Divān of Shams of Tabriz. [3] But the Masnavi is quite a different sort of work. Its name – Masnavi in modern Persian or in Arabic transcription Mathnawī – means simply ‘couplet’ or ‘double verse’ from the Arabic numeral ithna, ‘two’. So it is named after a poetic form.

This was the genre of Sufi didactic, instructional works; the most famous one before Rumi’s was Attar’s ‘The Conference of the Birds’,[4] which tells of the journey of a group of birds seeking to find their king, the Simorgh. Rumi’s Masnavi became known as the Masnavi-ye Ma’navi, ‘Masnavi of Meaning’, and it was distinguished from all other masnavis because it is the most massive, the paragon and most important example.

A masnavi poem is long, but also highly memorable and repeatable because of its narrative story element. Also, the metre is eminently sustainable over very long passages. The length of Rumi’s work has grown slightly over the centuries, as copyists and editors have added to it. But there has been some wonderful scholarship done to find the earliest manuscripts, firstly by British scholar R.A. Nicholson – who also produced the first English translation [5] – and more recently by Iranian scholars, such as Mohammad Estelami, and most recently by Mohammad Ali Movahhed. In these there are some 25,500 couplets that are attributable directly to Rumi, which are equivalent to 51,000 lines of English poetry – around five times the length of Milton‘s Paradise Lost, and four times longer than Dante’s Commedia Divina. It is divided into six books, and we have just published the first two, with the rest to follow.

Rumi regarded the whole thing as a work that had a life of its own as revealed to him by God. This wasn’t a way of promoting himself to prophetic status, but he saw himself as a medium for its transmission. He passed away very soon after he got to the end of the sixth book.

David: You have mentioned R.A. Nicholson’s translation, which is still widely used and respected. Why have you felt the need to produce a new version?

Alan: Nobody can replace Nicholson’s work. He was the first westerner to edit and translate all six books, but as a Cambridge scholar in the 1920s he regarded editing and commenting – scholarly commentary – as rather more important than doing a ‘crib-sheet’ for students of Persian. His translation is a very good one, excellent because it’s so literal, but it’s not really for modern public consumption because it just flies way over everyone’s head. It was done into a deliberately archaic style of English in imitation of the King James Version of the Bible, which was itself archaic even in its own day.

The most important thing, for me, is that anyone who tries to read the Masnavi in Nicholson’s English alone would not be aware of the richness of the original Persian poetry. I had to learn Persian to discover this for myself when I was a student in Oxford nearly fifty years ago. In translating it now I have tried to do a double job, which is to be as literal as possible, but also to anchor it onto a comparable metre in English, which is the iambic pentameter of blank verse.

David: Can you explain why you have used this metre, which is not the same as the original?

Alan: The ramal metre, the mystical metre of Rumi’s Masnavi, means ‘running’, but it is quite complex to the English ear. It is a driving, syncopated rhythm. The metrical pattern is summarised in the Arabic phrase fāʿilātun fāʿilātun fāʿilun, that is 11 syllables, 22 in the full couplet, i.e. (reading from left to right), where — is a long syllable and ∪ is short:

— ∪ — — / — ∪ — — / — ∪ —

— ∪ — — / — ∪ — — / — ∪ —

It is quite different from the pentameter metre, which visually looks more pedestrian:

∪ — / ∪ — / ∪ — / ∪ — / ∪ — / (∪)

∪ — / ∪ — / ∪ — / ∪ — / ∪ — / (∪)

I have used it in English because of the great wealth of literature there is from Shakespeare onwards – Milton and Wordsworth also used it, for example – in which blank verse has been developed and enriched by centuries of use. The English ear is accustomed to it, so it’s an ideal form for translation, especially for dramatic narrative and dialogue.

So what I’m trying to do in my translation is to liberate the poetry from a prosaic prison, something similar in a way to what Coleman Barks has said he was trying to do in his well-known renderings, working with the old translations in front of him.[6] I’ve gone back to the Persian verse, and am trying to be as faithful as I can to the text. It’s sometimes very difficult to find the right words in the right order, because Persian poetry is so much more concise – lacking definite and indefinite articles, pronouns and all the auxiliary verbs of English, for example.

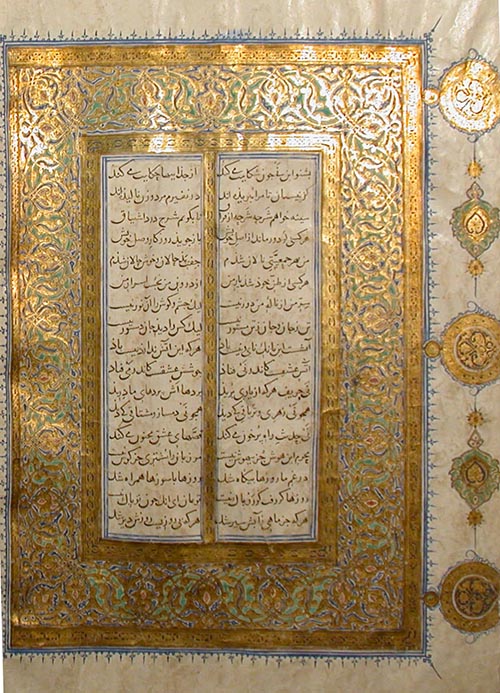

The Masnavi, Konya G Manuscript, the oldest copy of the text, kept at the Mevlana Museum in Konya. Image: courtesy Dr Naci Bakırcı, Assistant Director of the Mevlana Muzesi, Konya

Rumi’s ‘Bigger Voice’

.

David: You’ve taken the rather bold approach of including the Persian text in the books.

Alan: Yes, I asked an Iranian academic, Professor Mohammad Este’lami, if I could incorporate his edition of the Konya G Manuscript, and he was delighted. This is the manuscript on display in the Mevlana Müzesi in Konya and it is the oldest version we have. Nicholson, interestingly, worked initially from other sources and was into the third book before he found this manuscript, and he revised his translations after seeing it.

To have the text along with the translation, so that Iranian and western academics/mother-tongue speakers have the original there in front of them, is, as you say, a risky thing to do. But I’m taking that risk for the sake of transparent translation, and not hiding anything. Translation is interpretation: the very word is a Latin form of the Greek ‘metaphor’. According to the philosophy of Rumi and the Sufis, everything is in a sense translation, a version of a version, and of course philosophically, even we are ‘versions’ of our eternal realities – manifestations in form. So one is always only approximating the original form of the poem.

But I’m hoping that by looking more at the spiritual form of the text – by looking at both the micro-structure and macro-structure of the poem – to go beyond just the mere words. When you look at what Rumi is actually doing dynamically, you can identify that ‘something else’ – a bigger voice – is heard. And that is the mind of Rumi. I’m trying to translate not just words, but what I hear as the mind of Rumi as he is working through the text.

David: What do you think is happening with this ‘bigger voice’?

Alan: Well, Rumi himself sometimes seems to fall into ecstatic states while speaking: he is sharing his insight and opening himself to the reader and practising meaning. And this is why the book is known as the Masnavi-ye Maʿnavi, the ‘Masnavi of Spirit’ or ‘Masnavi of Meaning’. He wants not merely to define in words but to take us to that world of ultimate meaning, which is way beyond any mental conception. Even to talk about it as ‘Being’ is to degrade it.

I think ultimately his example has a subtle effect on the reader – a kind of osmotic effect. I have referred to this as what J.G. Bennett and Gurdjieff called a ‘legominism’, because I do think that the act of reading such a text as the Masnavi has a cathartic and uplifting effect on the reader. It does this because it is working at a subtle level. Of course, some other poetry has a similar wonderful effect (Milton’s Paradise Lost, for example), but it is clearly true of the Masnavi.

Dervishes of the Mevlevi order, founded by Rumi’s son Sultan Valed, at the sema’ ceremony, Saruhan Caravanserai, Sarıhan, near Avanos, Cappadocia. Photograph: imageBROKER [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

Open Heart Surgery

.

David: You have mentioned that one of the features of the masnavi form is that it is based upon narratives that make it easy to follow and remember. But the stories in Rumi’s Masnavi are extended and often apparently quite rambling, hard to keep track of.

Alan: Actually, I think we are misled by what appears to be the predominant feature of the text, namely story. I’ve done some analysis of the text of the second book and found that the 65 stories and anecdotes occupy only 1,650 of the total 3,836 verses (44%) and the other 2,146 verses (56%) are taken up by nearly 100 different discourses, reflections and commentaries. Many people will begin reading the Masnavi mostly for the pleasure of the stories, but they will find that there is much more going on besides.

I’ve described the experience of reading the Masnavi as ‘open heart surgery’, qualified with the subtitle ‘The Operation of Divine Love in the Masnavi’.[7] (To listen to a version of this talk, click here [/]). I got my comeuppance for this just a few weeks ago, when I received a formal invitation from the Dean of the University of Jordan asking me to referee an internal promotion to a Chair in their Cardiology Department. They assumed that having written on open heart surgery that I must be a cardiologist!

In my paper I describe the story narrative as the anaesthetic by which the divine surgeon puts the intellect to sleep: in this state of reverie or relaxation, the Masnavi acts as a heart-lung machine to keep the reader alive. The diseased heart is then replaced by a new heart purified of selfhood.

Rumi layers his writing, beginning a story and then moving into telling another story within that story, and another one within that. This has the effect of disorienting the reader, creating a sense of dislocation from the self, from the mind, and the intellect is befuddled. Within this nesting, or layering, he introduces many voices, moving between the high and low registers, just like the neyzen (ney-player), who, by blowing harder on the flute, brings the notes up an octave. This is what Rumi does; he changes the octave and escalates the tone, switching the reader/listener into another mode. (To hear the sound of the ney, see video right or below.)

Video: Hicaz Taksim. Duration 2:17 minutes

David: The mention of the ney brings us to the famous opening couplets of the Masnavi, which have been called “the most captivating ever written, even in comparison to Shakespeare, and fill the heart of the reader with sadness”. Can you comment on the opening lines?

Alan: Such melancholy is characteristic of much Persian poetry and music. It sounds melancholy, but of course what it’s doing is pulling the heart – pulling the heart upwards – to reach beyond sensuality to something truly tender. An example on a grand scale is the opening few minutes of Bach’s St John Passion which, with its discordances in the woodwind, is tremendously evocative of the Passion Bach is about to unfold musically. Rumi’s Neynāme, ‘the Song of the Reed’ has that character, because it is an intimate tugging at our heart strings; it is Rumi’s invitation to come into the Masnavi. (To hear Alan reading the whole passage, click the audio modules below.)

Listen to this reed as it is grieving,

it tells the story of our separations:

Since I was severed from the bed of reeds,

in my cry men and women have lamented.

I need the breast that’s torn to shreds by parting,

to give expression to the pain of heartache […]

The reed-flute’s sound is fire, not human breath.

Whoever does not have this fire, be gone!

It is the fire of love that’s in the reed,

the turbulence of love that’s in the wine.

I do find that particular passage very moving, but there are many other passages like that, which may be missed by those who are just looking for stories.

David: You said earlier that the Masnavi is an inspired book. But you also point out that it is a highly structured piece of work.

Alan: Yes indeed, and that’s important. I’ve tried to explain that there is a stable structure to it, that there is a cyclicality, a cycle of seven different voices that start at the highest level of spirituality and come down to earth with the story, and then re-ascends through analogy, dialogue, moral discourse or homily, ecstatic discourse, and back through hiatus to a point of silence.

You can hear this in the recording I have made for this interview (click the audio module below). In this ecstatic passage, he goes through all seven voices in a matter of a few lines, starting with the parrot talking to her owner, then the merchant who is going to relate her story to the parrots in the forests of India, then the reader is suddenly witness to her addressing God Himself. There’s just no doubt about that, because it then turns into a kind of zikr (remembrance) towards the end and you can see that he comes to a point of passing out.

Even the smallest element of the book – the single masnavi couplet – is powerful and interesting in this respect. Its two-part structure means that it can answer itself: so each verse is in dialogue with itself. There is also an enormous amount of wordplay going on in the text, which is a challenge to the translator.

David: It seems to me that one of the things you have tried to do in your introductions is give the reader a way of negotiating a way through this vast text. For instance, you have drawn a diagram of the way these seven voices interact.

Alan: When I was teaching this subject to students I provided a kind of navigational chart for them, so they could spot where they were situated on the ocean and not get lost. It’s possible to identify where you are from linguistic features of the text. In a story or analogy, everything is in the past tense. In a discourse, it’s in the present and future. In a moral homily, there is constant reference to imperatives and texts of admonition and challenges. In ecstatic discourse there is a constant present, a ‘now’ of accelerated and evanescent exclamation. Even when there is a sense of being becalmed in a vast passage, there is the feeling of the deep oceanic swell of the Masnavi.

One of things I have discovered is that Rumi the poet is himself moving throughout the Masnavi. Books 2 and 3 are much darker than the first: there is more madness and bewilderment, and the development of soliloquy. He no longer has to pull the reader out of the story into the text of a discourse, he just continues by making the story go into a dramatic dialogue, where a soliloquy doubles as his own voice, the voice of Mowlana. It makes it a dickens of a job to translate, and even more perplexing to punctuate.

Commemorative Coin produced by UNESCO to mark the 800th anniversary of Rumi’s birth. For more, click here [/]

The Universality of Rumi

.

David: Professor James Morris mentions on the edition of your book that Rumi’s work is “the mirror of our innermost state” and it seems that his work is much more challenging – or that you are delivering a much more challenging version – than is implied by his super popularity these days as a poet, particularly in the United States?

Alan: That is right. What Coleman Barks did was to ‘normalise’ or to de-islamicise the Masnavi and the ghazals, to take the Islam out of them. And I can see why he wanted to do that.

David: By ‘Islam’, you mean the religion or the spiritual tradition?

Alan: No, he’s not really trying to take the spirituality out, although it has changed because, in taking the Islamic aspect of it out of it, he has turned it into more psychological than spiritual wisdom.

David: Perhaps a bit like mindfulness and Buddhism?

Alan: Exactly so. I don’t make a big thing of it, but I would see this as similar to pretending that Chaucer, Dante, Shakespeare or Milton were not writing from within a Christian milieu. There is no doubt that the Masnavi is constantly echoing the Quran and hadith. Some ‘Rumiphiles’ deny this, and refuse to accept either the Islamic or Sufi nature of the Masnavi and view it as purely universal. They are entitled to that view, but I am to mine too.

David: If people are to get the best out of reading this work, what kind of preparation would you say they need? What sort of frame of mind should they approach it in?

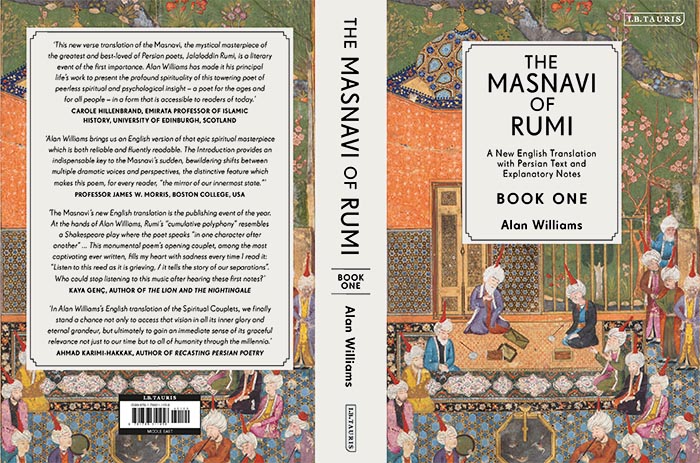

Alan: First of all, it has to be taken seriously. And that is why I kind of have a problem with what I could call ‘Rumi Lite’. What I’ve tried to do by putting the Persian text into the publication, is to show graphically that this is not something of the 20th–21st century, not something American or English, or modern at all. It is in some ways foreign and alien to this world of ours. I’ve indicated this to the reader semiotically, using colour illustrations from the oldest manuscripts and miniature paintings on the dust jackets from 500 years ago, so that they can see that this is a text from another era and another world.

Also, because I have included everything, I’ve not made it easy for readers. If I say it’s a terrific read, I mean that in another sense as well – it’s a very long read, and some people are going to fall asleep. Perhaps the volumes should come with their own bookstand as well as a ribbon, because these heavy books are going to be dropped if the reader drops off! In fact, Rumi occasionally chides his own audience for falling asleep while he is talking; he knows that his words lead to other states of consciousness, one of which is sleep.

So it is a challenging read and the only preparation I can offer is my own introduction, where I’ve tried to prime the reader for the rollercoaster that it is. The only way readers can prepare themselves is to dive in and be drowned in it. But Rumi is a very kindly man and calls on you the reader as ‘son’, ‘brother’, ‘uncle’, even ‘father’ – in Persian these words can be said euphemistically, and are not always endearments, as they sometimes chide the reader as ‘lazybones, wake up!’ But there is also a strong connection, in that it is always addressed to you: you, David, and You, God. Sometimes he segues directly from one ‘you’ into the other You.

David: How long has it taken you to get this far? And how much longer before the whole work appears?

Alan: I’ve been working on it for decades. In 2000, I was invited to do a paperback of the Masnavi for Penguin Classics. They wanted me to do an anthology, and I said no, I want to translate the whole fish, not fillet it. But they already had books by Coleman Barks, and didn’t want any more than one volume. After Spiritual Verses [8] was published in 2006, I went back to writing about what I knew best, Zoroastrianism. But I was always looking for a publisher to take on the whole of the Masnavi and it took me several years to find one, when Iradj Bagherzade of I.B. Tauris kindly agreed to the project.

I’m now well over halfway through, but it will take me another few years to finish all six books. I hope to publish one volume a year. I’ve had great fortune in having a lot of research sponsorship from the British Academy and then from the Leverhulme Trust, which has allowed me to dedicate myself to the project full-time.

David: You have been involved more generally in projects such as the Mevlana Rumi Review, [9] whose aim is to redress the lack of attention in world literature to the works of Arabic and Persian thinkers. Do you see this translation as adding to world literature?

Alan: Absolutely. I’m hoping that my publisher will send the books to journals like the London and New York Review of Books and other literary heavyweights, because I want the ‘mainstream’ to review them so that they don’t just get consigned to a ‘New Age’ periphery of publications.

This is an edited version of a longer interview. For a full transcript, click here.

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: The legendary meeting of Rumi and Shamsoddin of Tabriz, depicted in Jāmi al-Siya by Muhammad Tahir Surahvadi, 17th–18th century, Topkapi Palace Museum, H1230 fol 121a. Image: Wikimedia Commons.

First inset: Alan Williams. Photograph courtesy of Alan Williams.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] RUMI: The Masnavi of Rumi, translated by Alan Williams and including the Persian text by Mohammad Este’lami. (I. B. Tauris, February 2020).

[2] For an imaginative recreation of this relationship, see the best-selling book by ELIF SHAFAK: The Forty Rules of Love (Penguin, 2015).

[3] For selected translations, see:

R.A. NICHOLSON: Selected Poems from the Divani Shamsi Tabriz (Cambridge University Press, Reprinted edition 1952).

FRANKLIN D. LEWIS: Swallowing the Sun (Oneworld, 2008).

[4] FARID ʿATTAR: Conference of the Birds, translated by Afkhan Darbandi and Dick Davies (Penguin Classics, 1984).

[5] RUMI: The Mathnawi of Jalalu’ddin Rumi, translated by Reynold A. Nicholson (Gibbs Memorial Trust, 2nd revised edition, 2015).

[6] ALAN WILLIAMS: ‘Open Heart Surgery: The Operation of Love in Rumi’s Mathnawi’ in: LEONARD LEWINSOHN [editor]: The Philosophy of Ecstasy: Rumi and the Sufi Tradition (Bloomington, Indiana, 2014). p. 199–227.

[7] See for example COLEMAN BARKS: Essential Rumi (Harper Collins, New Edition 1995).

[8] RUMI: Spiritual Verses: The First Book of the Masnavi-ye Ma’navi, translated by Alan Williams (Penguin Classics, 2006).

[9] Mevlana Rumi Review, see https://brill.com/view/journals/mrr/mrr-overview.xml

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: The sound of the Turkish ney, played by Hicaz Taksim. Duration 2:17 minutes

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

The Unity of Humanity

Professor Todd Lawson on the universal vision of the Qur’ān

Mary, Seat of Wisdom and Mercy

This is the reality of Mary as expressed at Chartres: she is the completely receptive place in which wisdom appears

Bewildered by Love and Longing

Michael Sells and Simone Fattal talk about a new translation of Ibn ‘Arabi’s famous cycle of love poems Translation of Desires

The Zoroastrian Flame

Khojeste Mistree talks about one of the world’s oldest surviving religions and what we can learn from it in the present day

READERS’ COMMENTS

Thank you, David, for a very sensitive interview with Alan Williams and covering a wide scope in such an intelligent way.

Very interesting , good job and thanks for sharing such a interesting blog.

MUSLIMS

It’s my pleasure I read your article, and I collected the information and also really enjoyed reading your article. I must suggest all my friends read this poem. Anyway, I like to read books and also like traveling, and for this time, I will going to explore bus los angeles to las vegas.