Finance & Global Affairs _|_ Issue 28, 2025

George William Russell (Æ):

A Forgotten Irish Mystic

Gabriel Rosenstock gives a poetic response to twelve visionary paintings by the ‘myriad-minded’ writer and polymath, while Jane Clark and Peter Huitson give an overview of his life, work and legacy

George William Russell (Æ): A Forgotten Irish Mystic

Gabriel Rosenstock gives a poetic response to twelve visionary paintings by the ‘myriad-minded’ writer and polymath, while Jane Clark and Peter Huitson give an overview of his life, work and legacy

The Irish writer and mystic George William Russell (1867–1935), who wrote under the name Æ (or AE), was an extraordinary man – a painter, a poet, a newspaper editor, an economic theorist and, above all, a visionary. He was immensely influential in all these roles during the early years of the 20th century when Ireland was searching for a new identity independent of Britain. A contemporary and lifelong friend of W.B. Yeats, he was a seminal figure in the Irish literary renaissance, and a member of the Dublin Theosophical Society. He was also a banker and an economist who was an early advocate of sustainable development, his ideas forming the basis of Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal’ in post-depression USA. In this piece, Gabriel Rosenstock gives a poetic response, under the evocative title ‘The Fairy Path’, to Russell’s visionary paintings, and Jane Clark and Peter Huitson provide a brief biography of this remarkable man, whose legacy is now being rediscovered in Ireland.

The Fairy Path

by Gabriel Rosenstock

Irish sage George William Russell (1867–1935), known as Æ, is still remembered in Ireland but is little known elsewhere. A writer, an editor, a critic, a poet, a painter and an economist, he was also a mystic who in his book The Candle of Vision [1] describes having visionary experiences from an early age. He was a dynamic figure in the Celtic Revival which was a contributing impetus towards the move away from Britain in the early years of the 20th century – although he and so many other figures of the Celtic Revival were also part of British culture in many ways. His work with the cooperative movement gives the lie to the popular conception that people who are ‘away with the fairies’ are poor achievers when it comes to the tasks of practical life.

Though unique as a polymath, Russell was one of hundreds of distinguished men and women who worked for a spiritual awakening in Ireland during this period. Many of these stalwarts saw that the revival of the Irish language could play a part in all of this. The country’s spirit had been drained by traumatic events such as the Great Hunger of the 1840s during which the British Army came to the assistance of the landlords’ local militia to export a variety of foodstuffs to Britain. Those who did not die of starvation, disease and despair emigrated, often in ships known as ‘Coffin Ships.’ These events coincided with a language shift from Irish to English. What good was Irish if the emigrant’s ship was waiting, or a job in the British Army or Civil Service?

The Irish sage George William Russell (1867–1935), known as Æ, is still remembered in Ireland but is little known elsewhere. A writer, an editor, a critic, a poet, a painter and an economist, he was also a mystic who in his book The Candle of Vision [1] describes having visionary experiences from an early age. He was a dynamic figure in the Celtic Revival which was a contributing impetus towards the move away from Britain in the early years of the 20th century – although he and so many other figures of the Celtic Revival were also part of British culture in many ways. His work with the cooperative movement gives the lie to the popular conception that people who are ‘away with the fairies’ are poor achievers when it comes to the tasks of practical life.

The Irish sage George William Russell (1867–1935), known as Æ, is still remembered in Ireland but is little known elsewhere. A writer, an editor, a critic, a poet, a painter and an economist, he was also a mystic who in his book The Candle of Vision [1] describes having visionary experiences from an early age. He was a dynamic figure in the Celtic Revival which was a contributing impetus towards the move away from Britain in the early years of the 20th century – although he and so many other figures of the Celtic Revival were also part of British culture in many ways. His work with the cooperative movement gives the lie to the popular conception that people who are ‘away with the fairies’ are poor achievers when it comes to the tasks of practical life.

Though unique as a polymath, Russell was one of hundreds of distinguished men and women who worked for a spiritual awakening in Ireland during this period. Many of these stalwarts saw that the revival of the Irish language could play a part in all of this. The country’s spirit had been drained by traumatic events such as the Great Hunger of the 1840s during which the British Army came to the assistance of the landlords’ local militia to export a variety of foodstuffs to Britain. Those who did not die of starvation, disease and despair emigrated, often in ships known as ‘Coffin Ships.’ These events coincided with a language shift from Irish to English. What good was Irish if the emigrant’s ship was waiting, or a job in the British Army or Civil Service?

Immediately after Ireland achieved her freedom from Britain (political, if not cultural and linguistic) in 1921, the Church began to have an undue influence on the population. Theosophy became suspect, as did anyone associated with it, and the state meekly followed the dictates of the Church. This led to a confusing almost schizophrenic situation whereby children were encouraged to gather the folklore of their area, a folklore riddled with tales of the pagan Otherworld! Living in Ireland now, one can still feel a deep interest in spirituality, the Otherworld, and at the same time an orchestrated opposition to such forms of thinking.

In my celebration of Russell’s visionary paintings, I have chosen to write in Gaelic as well as English because Irish is Ireland’s senior language, the ancestral language, Europe’s oldest literary language after Greek and Latin. It’s nothing short of miraculous that it has survived, albeit on a list of endangered languages. I chose the poetic form of the tanka because Russell’s visions are timeless, beyond the paltry dictates of fashion. Tanka have a timeless quality as well, I feel. Their origin in the courts of Japanese emperors and retired emperors over 1300 years ago places them as the oldest versecraft still being cultivated today. Each poem consists of 31 syllables, arranged in a configuration of 5–7–5–7–7.

I’ve been producing a lot of spontaneous ekphrastic poetry in recent years, freestyle and strict-form tanka, the first volume of which was Every Night I Send You Flowers [/] in response to artwork by the French painter Odilon Redon who, like Russell, was steeped in the spiritual culture of India. We are living in an era in which a soulless guru – the smartphone – can answer every question we may have. Ekphrastic tanka do not answer any questions as such; they simply present us with a mystery. And we are in need of mystery.

Children Dancing on the Strand

ní den saol seo iad

is daoine maithe anois iad

táid scuabtha chun siúil

___beidh siad ag damhsa go deo

___imithe thar spás is thar am

no longer children

they have become Other Folk

they have left this world

___their dancing can never cease

___beyond space and time they dance

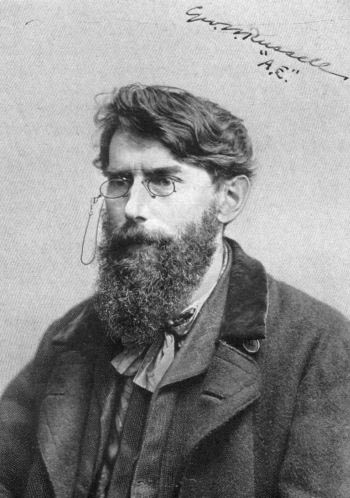

The Guardian of the Village

lasair is ea í

cosantóir an tsráidbhaile

nach bhfeiceann éinne

___ach an mhisteach is an ghealt

___soilsíonn sí an oíche dhóibh

a bright flame is she

the guardian of the village

there’s none to see her

___but mystics and lunatics

___she illuminates the night

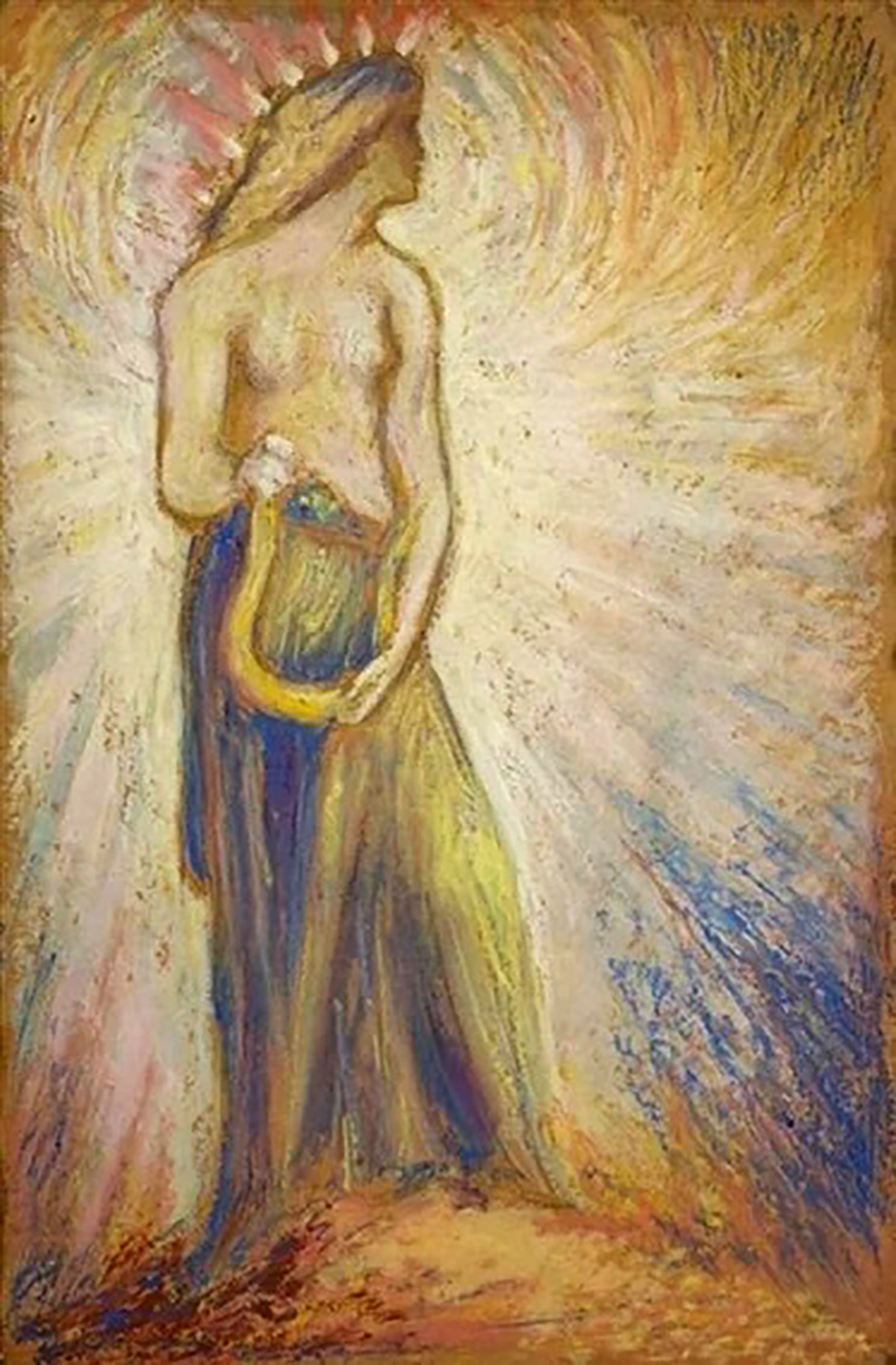

Lordly Ones (1913)

na Daoine Uaisle

níos sine ná na réaltaí

nach éadromchosach!

___bheifeá óg ina bhfochair

___slim sleamhain i measc na gcnoc

older than the stars

the ones we call the Gentry

light-footed they are

___’twould make you young to watch them

___sleek, nimble among the hills

Boglands

d’imigh frog as radharc

ní raibh finné ar bith ann

níor chualathas splais

___áit éigin sa Saol Eile

___d’oscail Bashō rosc liath

a frog disappeared

not a soul to witness it

and no splash was heard

___somewhere in the Other World

___Bashō opened a grey eye

The Spirit of the Pool

sna carraigeacha

sa loch, san abhainn is sa linn

i solas na ré

___líonann ár ndrithle féin

___an t-aer le siansa aduain

even in the rocks

in lakes and rivers and pools

in rays of moonlight

___the shimmer of our own soul

___fills the air with strange music

The Woodchopper and the Tree Spirit

connadh a dhóitear

cathaoireacha agus boird

tá spiorad iontu

___múinfidh sí a teanga dhúinn

___má taimid sásta éisteacht

the wood that we burn

our wooden tables and chairs

all is pure spirit

___she can teach us her language

___if we’re ready to listen

Mystical Figure in Winged Boat

ó, ní léir duit iad?

ná fan sna maotháin thosaigh!

lastall den inchinn

___ag seoladh leo faoi lúcháir

___an dream a bhí ann fadó!

you cannot see them?

move behind the frontal lobes

beyond rational mind

___there they sail in ecstasy

___good people of ages past!

Bathers

meallta ag an léas

an mhuir á pógadh ag an ngrian

tá leannáin ag tnúth

___ó cruthaíodh gleann na ndeor

___le léas a n-anama féin

light is drawn to light

the sun kisses the blue sea

lovers are pining

___since the beginning of time

___for the light of their own souls

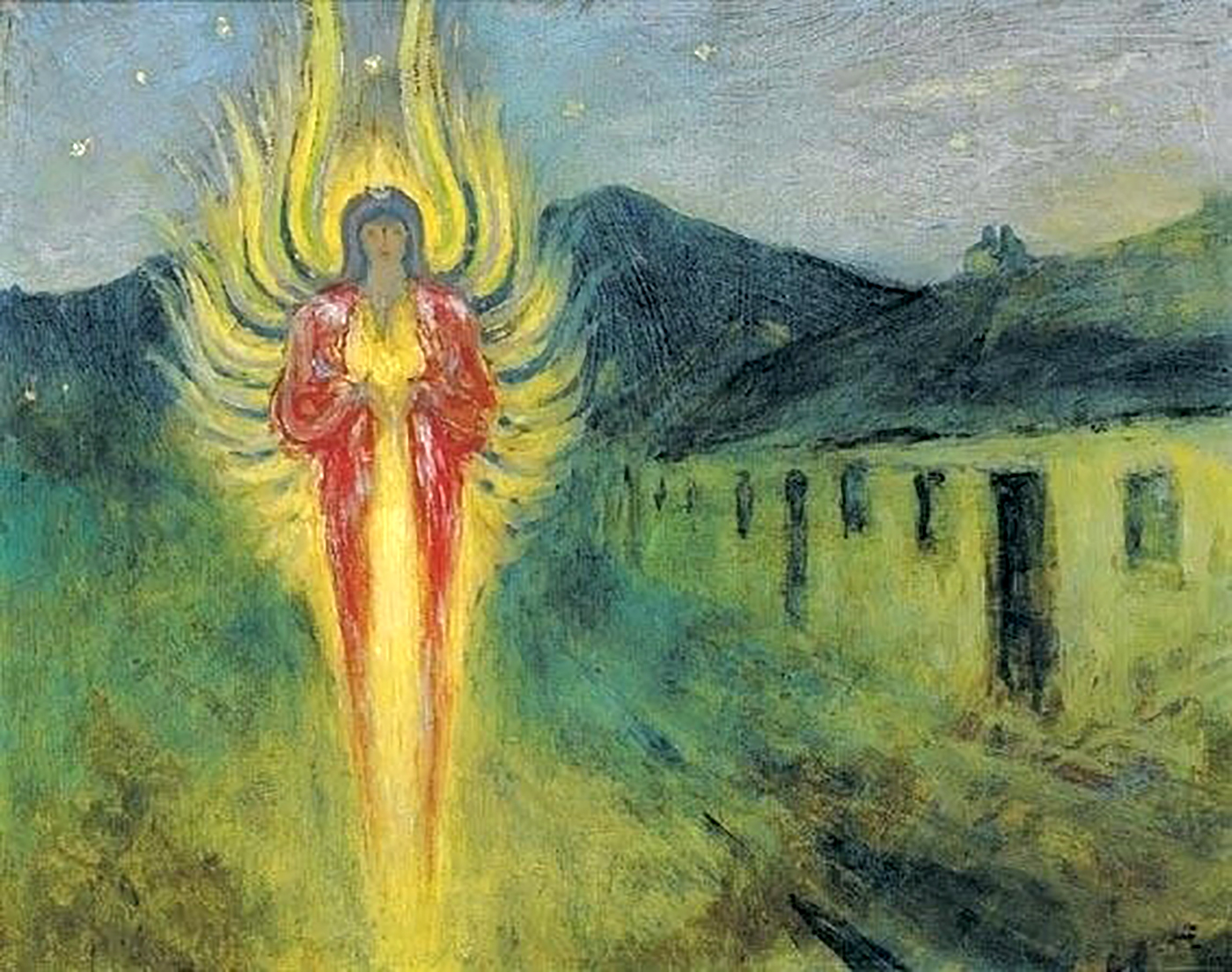

A Celtic Goddess Holding a Lute

bandia Ceilteach

tá sí fós ag seinm léi

i gContae an Chláir

___is i sléibhte Dhún na nGall

___sea, nílimid cloíte fós!

Celtic goddesses

their music is still alive

in the hills of Clare

___the mountains of Donegal

___something of us still survives!

Aeons as yet Unrolled

na haigéin suaite!

ach cé a ólfaidh an nimh?

níl slánú i ndán . . .

___bímis ag tnúth le síocháin

___ní shuaimhneofar na tonnta

churning of oceans!

but who will drink the poison?

none can save this world

___all we can hope for is peace

___but the waves – they cannot cease!

A Landscape with a Couple, and a Spirit with a Lute

is cuireadh caoin é

tar! a deir an ghealach linn –

’dtí doire an ghrá

___teithimid ón áit, ar crith

___roimh an ní atá aineoil

an invitation

come! says the blessèd moonlight

to the lovers’ grove

___and we flee the spot, trembling

___fearing what we do not know

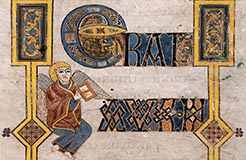

A Theosophical Mural

Detail from a mural painted by W. B. Yeats and George William Russell in the drawing room, at 3 Ely Place (former Theosophical Society meeting place), Dublin

oscail do shúile

tá d’anam féin dod’ chuardach

leis na mílte bliain:

___nach ligfidh tú isteach é

___cnag! cnagann sé ar do chroí!

open your eyes, now

your own soul searches for you

since time’s beginning

___let it enter now at last

___it is knocking at your door

Æ – A Brief Biography

by Jane Clark and Peter Huitson

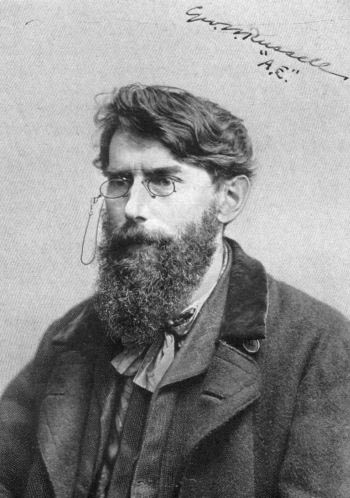

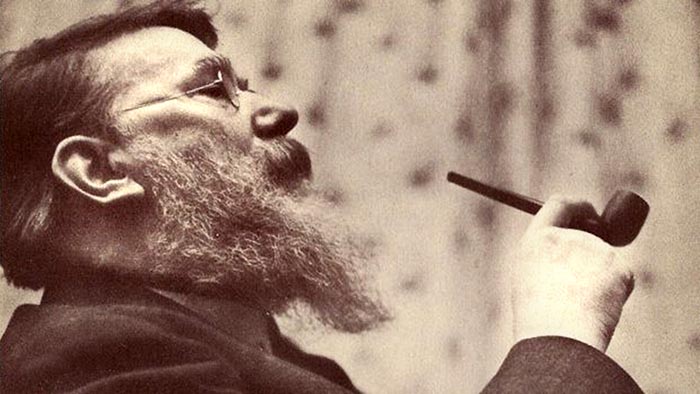

George William Russel, from Lurgan Ancestry [/]

George William Russell was born in Lurgan, County Armagh in Ulster on 10 April 1867 and moved with his family to Dublin when he was 11 years old. His early environment had a lasting influence on him, and the beautiful lakes and valleys of the countryside around Lurgan were the locus for the first of many mystical encounters with nature and spirit which he was to have throughout his life. From his earliest years, he felt a sense of intimacy with the natural world and what lay beneath it; he describes his first experience as happening at the age of three or four, brought on by a vision of daffodils. In his spiritual biography The Candle of Vision, he reveals the intensity of what he felt in the Irish landscape:

Somewhere about me I knew there were comrades who were speaking to me, but I could not know what they said. As I walked in the evening down the lanes scented by the honeysuckle my senses were expectant of some unveiling about to take place… The visible world became like a tapestry blown and stirred by winds behind it. If it would but raise for an instant I knew I would be in Paradise. Every form on that tapestry appeared to be the work of gods. Every flower was a word, a thought. The grass was speech; the trees were speech; the waters were speech; the winds were speech. They were the Army of the Voice marching on to conquest and dominion over the spirit; and I listened with my whole being, and then these apparitions would fade away and I would be the mean and miserable boy once more. So might one have felt who had been servant of the prophet, and seen him go up in the fiery chariot, and the world had no more light or certitude in it with that passing.[1] (pp. 11–12)

It was these visionary experiences that he was to later depict in his poetry and his paintings. As an artist, he was trained at the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin, which he attended immediately after leaving school. There he astonished everyone with his natural talent, but coming from a relatively poor background, he did not have the means to consider a career in art, going on instead to work in business. Nevertheless, he became regarded as one of Ireland’s best painters and was one of only three Irish artists featured in the famous Armory Show [/] in New York which introduced European art to America in 1913.

The countryside in Armagh where Russell spent his early childhood. Photograph: David Collins/iStock

Literature & Mysticism

.

It was at the Metropolitan School that he first met W.B. Yeats and formed a life-long friendship with him. They had a common interest in mysticism and the occult, and Yeats introduced him to the ideas of theosophy. In 1880 Russell was initiated into the movement, and when the Dublin Theosophical Lodge was founded in 1885 by the Indian teacher Mohini Mohan Chatterji [/], he moved into its premises in Upper Ely Place. He immersed himself in the study of Indian philosophy while supporting himself by working as a clerk in a drapery store. He found the work dull, but his contact with nature continued. He wrote that during this time:

[The] earth began more and more to bewitch me and to lure me to her heart with honied entreaty. I could not escape from it even in my busy office where I sat during week-days with little heaps of paper mounting up before me moment by frenzied moment. An interval of inactivity and I would be aware of that sweet eternal presence overshadowing me. I was an exile from living nature and yet she visited me. Her ambassadors were visions that made me part of themselves.[1] (p. 15)

During this period, he also joined the Irish Literary Society, which had been founded by Yeats and others in 1892, and this, in turn, led to his involvement in circles advocating the revival of Celtic culture and Gaelic. Then in 1903, he was one of the group – including Lady Gregory, Yeats and John Millington Synge – who founded the Irish National Theatre Society, which went on to become the Abbey Theatre. His play Deirdre – for which he also designed the ‘whimsical’ costumes and the set – was one of the first to be performed by the company.

He began his literary career with contributions to Irish mystical journals, and his first collection of poetry, Homeward: Songs by the Way was published in 1894.[2] It firmly established him in the Irish Literary Revival. In it, his occult side was fully expressed and he began to find a form for his supernatural beliefs in the magical character of Cú-Chulainn (Cuchulain) who was a legendary warrior hero in the Ulster Cycle of Irish mythology. His poetry was very highly regarded, and in the early years of the 20th century he was considered to be on par with Yeats, who said of him:

He [is the] one poet of modern Ireland who has moulded a spiritual ecstasy into verse… The most delicate and subtle poetry that any Irishman of our time has written.[3]

By the time Homeward appeared, Russell had already adopted the pen name by which he is best known, ‘Æ’ (or AE), derived from the name ‘Aeon’ which, within the gnostic tradition, is the term used for an aspect of god or divine intelligence. There are different accounts of how it was revealed to him; sometimes it is said to have been given in a vision, sometimes that he came across it while reading an entry on ‘Gnosticism’ in a book in the National Library. The story goes that he signed a literary manuscript with the full name, but the compositor could not read his handwriting beyond the first two letters and the abbreviation stuck.

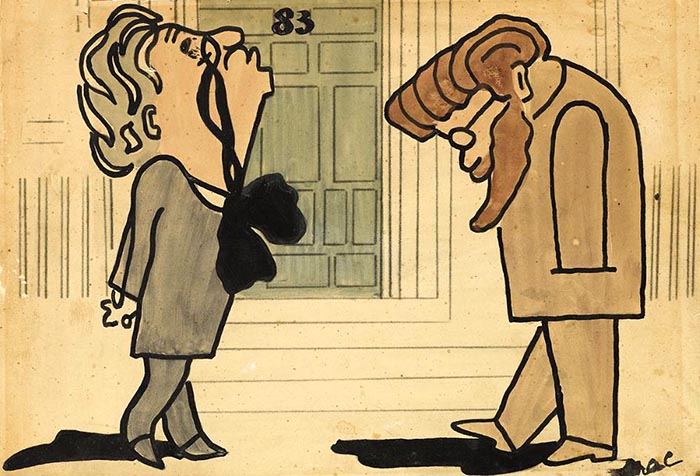

‘Chin Angles’ or ‘How the Poets Passed’ by Isa (Isabella) Macnie, depicting Yeats and Æ walking past 83 Merrion Square to visit one another without seeing each other. Apparently depicting a real event, the cartoon was published initially in the New York Times, then in the Irish Independent on 26 September 1924. Image from Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies [/]

Politics, Journalism and Economics

.

In 1897, Russell left his job as a clerk to embark upon a new career with the Irish Agricultural Organisation Society (IAOS), a cooperative movement founded by the social reformer Horace Plunkett [/]. He proved to be a highly effective organiser, becoming spokesperson for the IAOS and taking on responsibility for establishing many cooperative banks in the south and west of the country. At one level, his mission was the pragmatic one of simply tackling rural poverty, but he brought a wider dimension to the discussion, believing that workers on the land deserved respect and dignity. His work gave him the opportunity to translate the epic language of the heroic revival, of Cuchulain and the ancient heroes, into a practical discourse of reform.

In 1905, he became editor of Irish Homestead [/], the weekly journal of the IAOS, and remained in the job for nearly twenty years. The journal’s mission was to promote cooperation between rural communities and agricultural societies, but here again, Russell used it to elucidate deeper principles, promoting ideals of citizenship and self-help crucial to the formation of an independently functioning Ireland.

Following the Anglo–Irish treaty of 1922 and the founding of the Irish Free State, the Irish Homestead merged with the Irish Statesman and Russell was appointed editor, holding the post until the paper ceased publication eight years later. Under his direction, the Statesman acted as an international bulletin with semi-official status, and at a time of national transition it exerted an influence that no cultural journal has matched since.

Russell sought to promote the common good, advocating a mutually supportive society, civic commitment and cooperative economics, all designed to give each citizen a stake in the community. Never one to make barriers between different aspects of reality, he also made the paper a showcase for Irish culture and in its pages promoted a wide range of literary talent, including W.B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw, Helen Waddell, Patrick Kavanagh and James Joyce. On the demise of The Statesman, the Irish Times commented:

Russell, and The Statesman, were often accused by the more bigoted and ultramontane sections of the population of being pagan and anti-Irish, but what they really meant was that he stood for intellectual liberty at a time when almost everyone else was clamouring for some restrictions everywhere.[4]

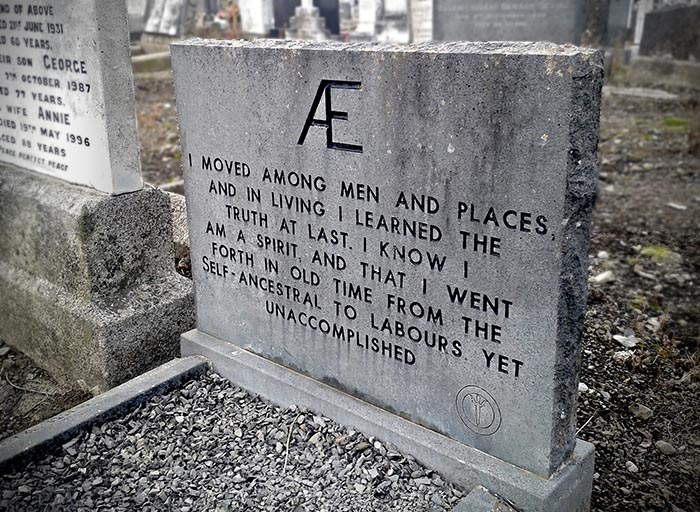

Unfortunately, by this time Russell had become unhappy with the Irish Free State. He felt that puritanism and censorship blocked intellectual and artistic freedom, maintaining that ‘The chief failure of the Irish is their submissiveness to the church – its tyranny poisons Irish life, especially in political affairs.’ Soon after the death of his wife Violet in 1932 he moved to England, where he died of cancer in 1935. His body was sent back to Ireland and is buried in Mount Jerome Cemetery in Dublin. It is said that 500,000 people took to the streets of Dublin at his funeral and the crowd following the procession was over a mile long.

Russell’s gravestone in the Mount Jerome Cemetery in Dublin. Image: comeheretome.com

Legacy

.

In 1930, Russell was one of the most influential people in Ireland, and his ideas had international reach. His articles on the economics of sustainable rural communities attracted the attention of Mahatma Gandhi in India and the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt in America. In the last few years of his life, he was invited on several tours of the USA, addressing packed meetings, accepting honorary degrees from universities, broadcasting on the radio and acting as advisor to the government. Much of the thinking behind the ‘New Deal’, which Roosevelt enacted between 1933 and 1938 to alleviate the worst effects of the Great Depression, was based on Russell’s ideas. Vice President Henry Wallace said of him:

Æ was a prophet out of an ancient age. He was one of the finest, most gifted, and most colourful people I ever knew. Never anything but the utmost humility, simplicity, sweetness and light. May God grant that the Irish may be able to produce such a man again.[5]

For us today, he stands as an inspiring example of someone who was at ease in both the material and spiritual spheres, exerting his talents and his passion in both realms and understanding how they can flow into and inform one another. The French writer Simone Tery brilliantly summarised his multi-faceted personality and interests in her book L’Ile des bardes as follows:

Do you want to know about providence, the origin of the universe, the end of the universe?

Go to AE.

Do you want to know about Gaelic literature?

Go to AE.

Do you want to know about the Celtic soul?

Go to AE.

Do you want to know about Irish History?

Go to AE.

Do you want to know about the export of eggs?

Go to AE.

Do you want to know how to run society?

Go to AE.

If you find life insipid –

Go to AE.

If you need a friend –

Go to AE.[6]

This last was an important and much-mentioned aspect of his character. He was famously generous with his hospitality and advice, and gave a helping hand to nearly every aspiring Irish writer of his age; the novelist Frank O’Connor termed him ‘the man who was the father to three generations of Irish writers’.[7] Among the many whom he supported were the poets Helen Waddell and Patrick Kavanagh and the novelist James Joyce. Joyce included a portrait of Russell under his pseudonym Æ in Ulysses, making fun of his eccentricities but also putting into his mouth this statement of his views: ‘Art has to reveal to us ideas, formless spiritual essences.’ [8] A more unexpected protégée was the Australian–British writer J.P. Travers, who met Yeats and Russell in the 1920s and went on to write the well-known children’s book Mary Poppins.

Russell’s reputation as an artist has not fared as well as that of his contemporaries such as Yeats and Synge, and for many years his work has been virtually forgotten even in Ireland. Similarly, his political and economic vision has been largely eclipsed by an increasingly materialist culture. But there are signs that this is now changing and there has been a recent upsurge of interest in his life and work. Since 2017, there have been successive annual festivals in his hometown of Lurgan, County Armagh; several new books have appeared, and a new National & International Society was formed in Dublin in 2023 with the ambitious plan of creating a new cultural centre based on Æ’s legacy.

Clifford Bax in the introduction to his essay collection The Hero in Man published in 1909 sums up his legacy like this:

To read these essays […] is to recognise one who has endeavoured always to communicate the ‘best in himself’, and the mood which they induce is a mood from which we may see the world once more in its primal beauty, may recover a sense of the long-forgotten but inextinguishable grandeur of the soul.[9]

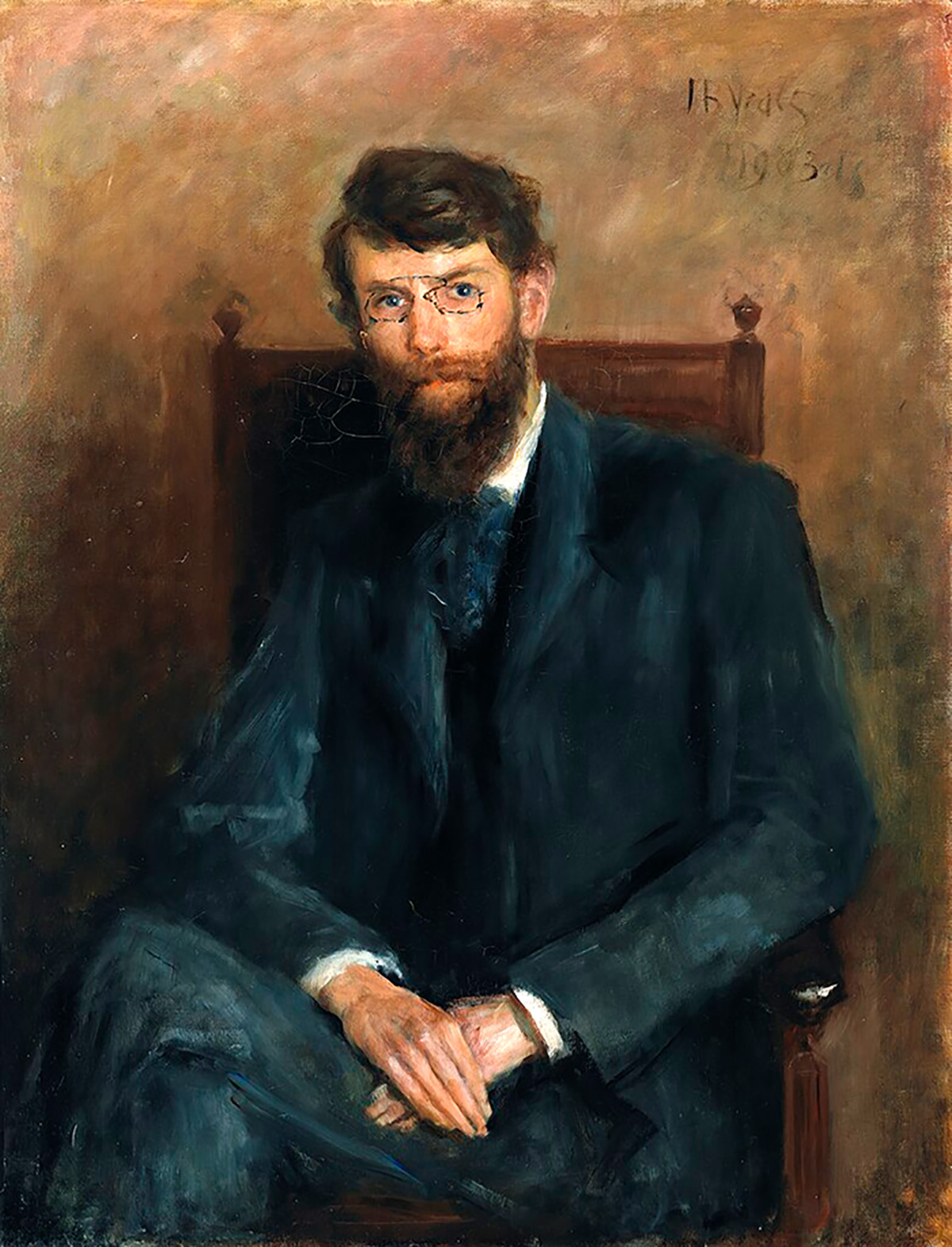

John Butler Yeats: Portrait of Æ. Image: National Gallery of Ireland via Wikimedia Commons

Gabriel Rosenstock [/] lives in Dublin and writes chiefly in Irish Gaelic. He is a poet, essayist, tankaist and haikuist. He is also a widely published children’s writer and translator. He blogs at roghaghabriel.blogspot.com

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: All the Russell paintings are in The National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin. Images via Wikimedia Commons.

Inset: George William Russell. Photograph: Project Gutenberg eText 19028, via Wikimedia Commons.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] Æ (GEORGE WILLIAM RRUSSELL), The Candle of Vision: The Autobiography of a Mystic (Azafran Books, 2019).

[2] Æ (GEORGE WILLIAM RUSSELL), Homeward: Songs by the Way (MacMillan, 1918).

[3] Quoted in MICHAEL McKERNAN ‘Ireland’s Forgotten Genius, George “AE” Russell’ in Celtic Junction Arts Review, Issue 23 [/]

[4] The Irish Times, 18 July 1935, p. 8.

[5] Vice President Henry Wallace quoted in MICHAEL McKERNAN ‘Ireland’s Forgotten Genius’

[6] SIMONE TERY, L’Ile des bardes (E. Flammarion, 1925).

[7] FRANK O’CONNOR, My Father’s Son, (Pan Books, 1971) p. 111.

[8] JAMES JOYCE, Ulysess, Episode 9.8.

[9] Æ (GEORGE WILLAM RUSSELL), The Hero in Man (Orpheus Press, 1909).

The text of this article has a Creative Commons Licence BY-NC-ND 4.0 [/]. We are not able to give permission for reproduction of the illustrations; details of their sources are given in the captions.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

The Book of Kells

James Harpur ‘takes a line for a walk’ as he remembers the challenges of writing his poem ‘Kells’

Rosemary Haughton (1927–2024)

Phoebe Ryrko remembers her grandmother, an inspiring theologian and activist who saw the divine in everyday life and human relationships

An Artisan of Beauty and Truth

The extraordinary poet, novelist, activist and painter, Etel Adnan, who died in 2021 at the age of 96, talks about her art and her philosophy of life

Building Jerusalem: The Encompassing Vision of William Blake

Susanne Sklar provides insight into the meaning of the famous ‘Jerusalem’ hymn

READERS’ COMMENTS

Brilliant! Thankyou! So valuable,freeing for the soul and sharing,caring for us all.For us to likewise.

I was transported by these luminous paintings and poems and feel inspired to pick up a brush!

Thanks to all at Beshara Magazine!

Patricia

My book of poetry is ‘Pure Spirit’. Many thanks. Prayers, Alan