Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 19, 2021

Building Jerusalem: the encompassing vision of William blake

Susanne Sklar provides insight into the famous ‘Jerusalem’ hymn

Dr Susanne Sklar has made a special study of the epic poem Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, written by the English visionary poet William Blake (1757–1827). Her book Blake’s Jerusalem As Visionary Theatre: Entering the Divine Body [/] [1] argues for an imaginative reading of this multi-faceted work, showing how it is based on a way of being in which all things interconnect – spiritually, ecologically, socially and erotically. In this article she shows how Blake’s vision of Jerusalem – and particularly his economic vision – can extend our understanding of the famous hymn of the same name, which has become a kind of unofficial English national anthem, and reveals its relevance to our contemporary situation.

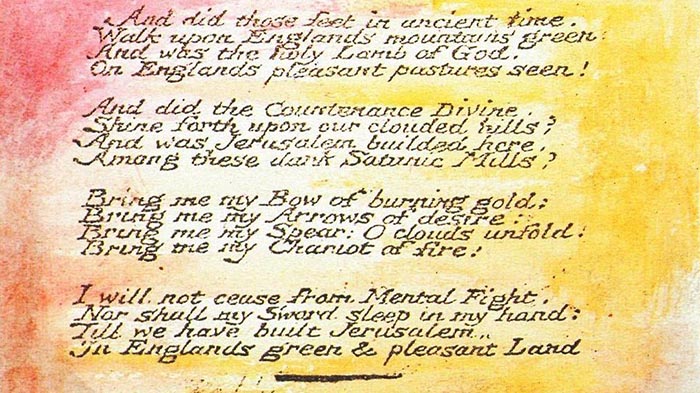

For over a century Britons have been singing these verses by the poet William Blake:

And did those feet in ancient time,

Walk upon England’s mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God

On England’s pleasant pastures seen

And did the Countenance Divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my Arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold:

Bring me my Chariot of Fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In England’s green & pleasant Land.

Blake wrote these words in 1804, as a preface for an illuminated book called Milton. They were set to music by Hubert Parry in 1916 and became what is often called England’s unofficial national anthem.

The original words of the hymn from the title page of Blake’s Milton. Image: Wikimedia Commons

However, the lyrics can be – and often have been – misinterpreted, and it is almost certain that very few people understand the full breadth of the vision which Blake was putting forward when he wrote them. As an American and a long-time lover of the works of William Blake, when I came to Oxford for doctoral studies focusing on his great illuminated poem Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, I was astonished to learn that the ‘Jerusalem’ hymn is often considered nationalistic, and has even been banned from some churches. For instance, in 2008 the Dean of Southwark Cathedral, the Very Rev. Colin Slee, forbade the singing of ‘Jerusalem’ in his church because he thought Blake was too nationalistic and he had no respect ‘for the glory of God.’ Earlier, in 2001, Rev Donald Allister, Vicar of Cheadle, would not allow ‘Jerusalem’ to be sung at a wedding because the hymn was a ‘nationalistic song that does not praise God’. [2]

Perhaps the stirring tune, celebrating ‘England’s green and pleasant land’, evokes fervent, though misplaced, nationalistic emotions. But such feelings negate the inclusivity of the Jerusalem Blake envisages and the way of life he hoped his work would inspire – a way of life which benefits all nations and every created thing. In fact, the cosmic drama that is played out in his notion of Jerusalem engages us with issues which are highly relevant to our global situation today.

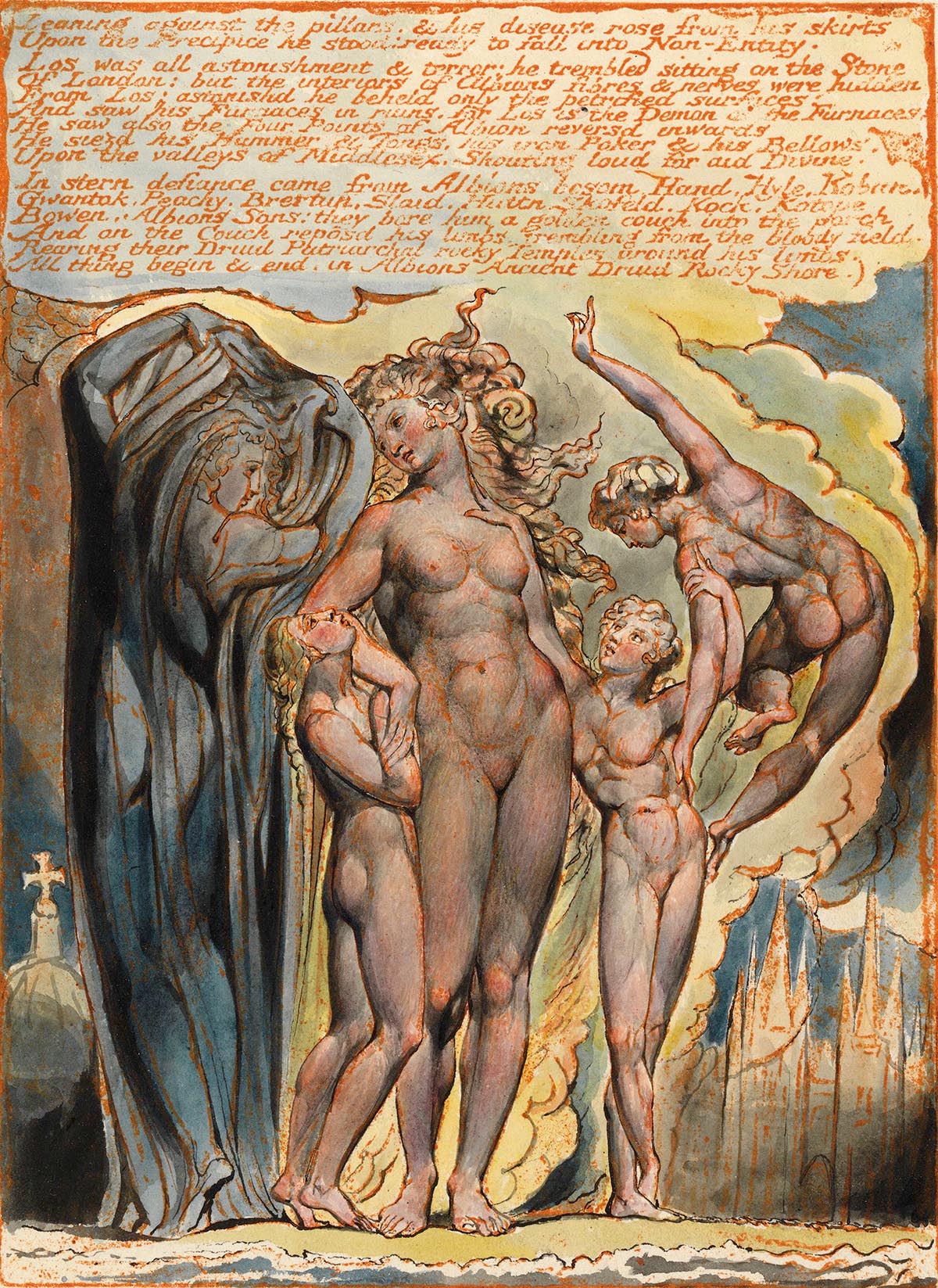

Plate 32: Vala veiling Jerusalem. Image: Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art

Move your mouse over the image to enlarge

Blake’s Economic Vision: Jerusalem – Or Babylon?.

Blake’s lyrics open with questions that have to do with the building of Jerusalem. He answers those questions in the epic poem Jerusalem – his masterpiece – which he began creating in 1804 and finally finished in 1821. In that long poem we learn that Jerusalem is a woman, a city and a way of life. She dwells in and with all people, walking always with Jesus throughout Albion (the ancient name for Britain), as well as in all nations. She abhors exploitation, and orchestrates what we would call ‘a global fair trade network’. Feminine-divine, the spirit of this sensuous bride of Jesus accords every created thing – including trees, rocks, and frogs – their unique identity. She is filled with love, even when Albion is not

By contrast, Albion, who is both an irascible ‘everyman’ figure and the land of Britain, is nationalistic. Blake portrays him as a figure stricken with a disease called Selfhood; today we would call it narcissism. In Jerusalem’s first scene, Albion banishes and negates Jerusalem, along with her many daughters. In Jerusalem’s way of being, inclusivity and forgiveness are social structuring principles, but Albion wants nothing to do with this. ‘Humanity shall be no more!’ he declares, ‘but war and princedom and victory! My mountains are my own and I shall keep them to myself…’

Such insularity creates spiritual, psychological, erotic, political, economic, and ecological ruin. Albion, the man and the land, chooses the way of Babylon (the Biblical city of luxury and corruption), embodied in a shadowy character called Vala. Vala/Babylon is very seductive, very toxic. Albion knows this – he knows he is making a bad choice but does it anyway.

O Jerusalem, Jerusalem I have forsaken thy Courts

Thy Pillars of ivory & gold, thy Curtains of silk & fine

Linen, thy Pavements of precious stones, thy Walls of pearl [3]

This description alludes to the vision of Jerusalem in the Book of Revelation. Those pillars, curtains, and pavements belong to God, not to any one person or nation. In Blake’s vision, all can participate in the sensuous Kingdom of Heaven in and through imagination. Albion knows this:

O Human Imagination, O Divine Body I have Crucified,

I have turned my back upon thee into the Wastes of Moral Law.

There Babylon is builded in the Waste, founded in Human Desolation. [4]

Albion uses ‘Moral Law’ to elevate himself and his deluded sons above others, promulgating a consumer society. He knows this is not healthy:

Thy severe Judge all the day long proves thee, O Babylon,

With provings of destruction, with giving thee thy heart’s desire. [5]

By ‘giving thee thy heart’s desire’ Blake indicates that Babylon is driven by the need for gratification – material gratification. This is a poor, self-centred substitute for love, and can never be satisfied – thus spawning human oppression:

The Walls of Babylon are Souls of Men, her Gates the Groans

Of nations, her Towers are the Miseries of once happy Families. [6]

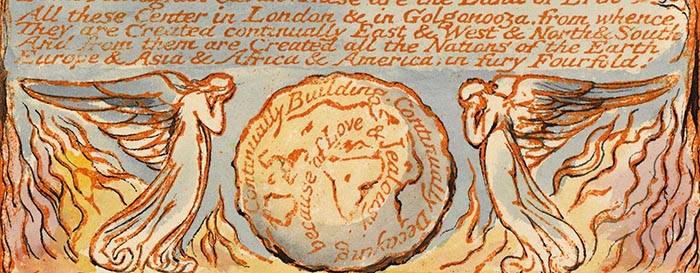

From Plate 2: Jerusalem sleeping (winged with six wings). Image: Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art

A Vision of Fair Exchange

.

But for Blake, trade need not necessarily be blighted by exploitation. Free trade can be fair (in both senses of that word), and Albion sees this.

Yet thou (O Babylon) wast lovely as the summer cloud upon my hills

When Jerusalem was thy heart’s desire, in times of youth & love.

Thy sons came to Jerusalem with gifts; she sent them away

With blessings on their hands & on their feet, blessings of gold

And pearl & diamond: thy Daughters sang in her Courts. [7]

Thus Vala/Babylon is meant to be within Jerusalem; art and manufacturing have their place in a healthy world. Babylon’s productivity can serve Jerusalem; commerce can bring joy, spreading – in generous exchange – through every nation:

From bright Japan & China to Hesperia, France, and England

Mount Zion lifted his head in every Nation under heaven. [8]

This is not an abstract fellowship; it is a form of spiritual materialism – capitalism transfigured:

In the Exchanges of London every Nation walk’d

And London walk’d in every Nation, mutual in love & harmony. [9]

‘The Exchanges’ refers to the Stock Exchanges, formally founded in London in 1773 (and regulated in 1801). In Jerusalem’s way of being the Exchanges are a place of mutual harmony, spreading ‘Visions of regeneration’ throughout the earth.

Jerusalem’s second chapter opens with a ballad in which Jesus and Jerusalem walk throughout England, bringing divine light to London’s neighbourhoods, villages, and at least two pubs: the Jew’s-harp-house & the Green Man.[10] All are ‘Children of Jesus & his Bride’.[11] This is a vision of Eden and Eternity, sadly blighted by Selfhood. But when Selfhood, ‘self-righteous pride’, is annihilated [12] Jesus declares:

In my Exchanges every Land

Shall walk & mine in every Land

Mutual shall build Jerusalem

Both heart in heart & hand in hand [13]

From Plate 95: Albion arising in wrath. Image: Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art

Expanding Economics

.

It is important to note that the building of Jerusalem, in which every nation participates, is not merely economic. In the poem’s fourth and final chapter, Jerusalem herself lets us know that commerce is ancillary to art, beauty and music. ‘I taught the ships of the sea to sing the Songs of Zion!’ she declares. [14]

Intercultural exchange, when orchestrated by Jerusalem herself, is more like a symphony than a spreadsheet. Perennial enemies, like Turkey and Greece, take the harp, the flute and a mellow horn – contributing delightfully to the song of ‘Jerusalem’s joy’.[15] Canaanites and Moabites (who lived in what we call the ‘West Bank’ these days, and are therefore equivalent to Palestinians) dwell with Israelites in harmony as Jerusalem’s silver bells ring out in ‘comforting sounds of love’.[16] Art, music and beauty are the ‘bottom line’ in Blake’s vision of Jerusalem.

No one is oppressed. As in music, harmony is based on difference, uniqueness, distinction. It is impossible to play a symphony if the woodwinds are being attacked and the brass are starving. Each instrument and every player contributes to the beauty of the whole.

Creating a world where no one is abused or oppressed necessitates a restructuring of cultural values and the annihilation of toxic prejudice. And this is not simple; it requires what Blake calls ‘Mental Fight’ in the final verses of the hymn. Thus the bow of burning gold, the spear, and the chariot of fire, equip us for a combat as rigorous as anything merely corporeal. Forgiveness can be ferocious!

In Jerusalem we learn that such warfare opens hidden hearts with ‘Wars of Intellect, Wars of Love,’ shattering the narcissistic assumptions that exploit, oppress and terrorise the poor, the weak and those of different faiths or races. Mental fight establishes a culture in which each is responsible for all, ‘even tree metal earth & stone’ [17] and the beauty of each created thing is to be honoured. Building Jerusalem in England connects its ‘pleasant land’ to every culture and nation, every ecosystem.

In Blake’s vision we are each members of the divine body, connected to all creatures. There are no hierarchies. Life flourishes intersubjectively, in what Blake calls ‘visionary forms dramatic’, with indestructible joy.

From Plate 72. Image: Courtesy of the Yale Center for British Art

The original version of Jerusalem is in the Yale Center for British Art and has been digitised in high resolution. It is freely available for viewing or editorial use. Click here to view [/].

Dr Susanne Sklar has taught and written about William Blake in seven countries; presently she lectures and tutors at Oxford and in London. Her book Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ As Visionary Theatre (Oxford University Press, 2011) should soon become a user-friendly guide for Blake’s great illuminated poem

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Jerusalem Plate 92: Jerusalem Rising. Image: Courtesy Yale Centre for British Art.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] SUSANNE SKLAR, Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ as Visionary Theatre (Oxford University Press, 2011).

[2] SOPHIE BORLAND, ‘Cathedral bans Popular Hymn ‘Jerusalem,’ Daily Telegraph, 9 April 2008. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1584578/Cathedral-bans-popular-hymn-Jerusalem.html

[3] WILLIAM BLAKE, Jerusalem:The Emanation of the Giant Albion (J) Copy E, 1821, 24.17–19. All quotations are taken from this source. Plate and sometimes line numbers are included.

[4] Ibid. 24.24–6.

[5] Ibid. 24.28–9.

[6] Ibid. 24.32–33.

[7] Ibid. 24.37–41.

[8] Ibid. 24.48–49.

[9] Ibid. 24.43–44.

[10] Ibid. 27.24–25.

[11] Ibid. 27.20.

[12] Ibid. 27.26–70.

[13] Ibid. 27.85–89.

[14] Ibid. 79:33.

[15] Ibid 79.48–50.

[16] Ibid 86.25–30.

[17] Ibid 99:1.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

The Book of Kells

James Harpur ‘takes a line for a walk’ as he remembers the challenges of writing his poem ‘Kells’

The Ecology of Money

An interview with Ciaran Mundy, Director of the Bristol Pound, about alternative methods of financial exhange

Doughnut Economics

Kate Raworth’s new book asks: how we can reconcile the needs of humanity with the needs of the planet?

The Revival of the Commons

Political strategist David Bollier explains how a new economic/cultural paradigm is challenging the increasing ‘enclosure’ of wealth and human creativity

READERS’ COMMENTS

Thank you for this inspiring and pertinent article.