News & Views

Dom Sylvester Houédard: tantric poetries

Charles Verey reviews an exhibition at the Lisson Gallery in London.

11 March – 6 June 2020

Installation image. Photograph © Dom Sylvester Houédard; Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

This exhibition, tantric poetries, consists of ‘typestracts’ and translucent laminates from the Lisson Gallery’s collection of work by Dom Sylvester Houédard (dsh) (1924–92). The pieces exhibited are a part of Dom Sylvester’s widespread but as yet un-catalogued oeuvre in the concrete idiom, made by him between 1963 and 1972. Unfortunately, the exhibition is closed to the public until further notice because of the lockdown, but a short guided video tour plus the catalogue, etc., can be seen on the Lisson Gallery website and on artnet .

Dom Sylvester was a British Benedictine monk who spent most of his life at Prinknash Abbey in Gloucestershire. A man of extraordinary intellect, his interests reached far wider than is usual for a monastic priest. He was a well-known poet, remembered for his precise, abstract and graphic work on an Olivetti typewriter and as an articulate participant and communicator in the radical, creative expression of the 1960s, where he worked alongside figures such as Yoko Ono, Allen Ginsberg, and John Cage. He had a life-long interest in, and deep knowledge of, Eastern spiritual traditions, especially Buddhism.

In her notes on this exhibition, the curator, Dr Nicola Simpson, quotes him on the meaning of tantra, giving valuable insight into his underlying intentions in the work on display:

“Tibetan mysticism […] aims at liberation from all that is unreal […] it seeks attainment of a blissful knowledge of the Ultimate Reality […] The aids used in Tibet are based on the tantra (net, web, wovenness) between the inner and outer worlds. Forces and their events, consciousness and its objects, all form a single weave; and tantrism is the discovery or establishment of inner relationships between the matter and spirit worlds, between ritual and reality, between mind and the universe, between the microcosm and the macrocosm.” [1]

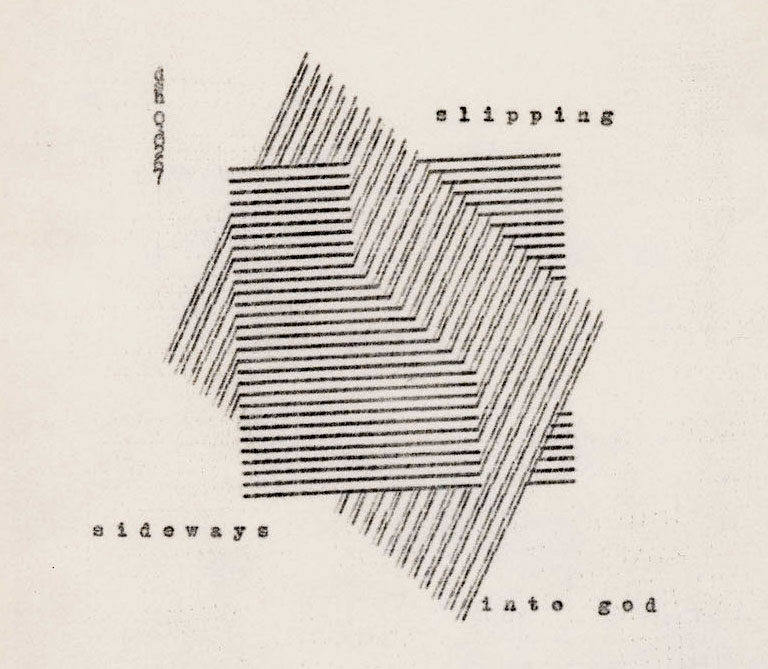

Typescript: “slipping sideways into god”. One of a series of Moiré poems, where the superimposition of two grids on top of each other is used to explore the way in which two different religions may offer coinciding views of a shared event, such as the experience of emptiness in meditative prayer. Photograph © Dom Sylvester Houédard; Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Projecting Mind States

.

The exhibition, designed and arranged by Dr Simpson, summarises the work that she has put into a decade of studying Dom Sylvester’s typestracts and laminate collages for the PhD thesis that she completed in 2019. [2]

She has assembled two rooms: one in which six groups of translucent laminate collages hang like stalactites, bearing reflecting crystalline messages; the other is an open room in which she has built a central mandala – or simple maze – of walls, in the form of a hollow cross, on which typestracts are displayed on either side, drawing the visitor to its centre from each of four directions. Effectively the cross is built with four identical sets of walls, each formed to make a square corner, pointing like an arrow-head towards the central space of the mandala. Each structure has two inner faces and two outer faces, a total of sixteen wall-spaces, on each of which a discreet group of typestracts is displayed. In addition, Dr Simpson has produced an excellent and necessary guide to the display, printed on both sides of a square sheet of paper, ingeniously folded in the basic form of the mandala structure.

Overall, the exhibition affords an opportunity for Dom Sylvester’s work to be seen in a format that does it justice; these tantric poetries, as we study them, become mind-states, projected onto the ever-fluent screens of our self-awareness. Perhaps the most essential point made by Dr Simpson’s presentation lies in its emphasis on the ‘keys’ that Dom Sylvester often included, in pithy verbal pointers, alongside the geometric, architectural, concrete forms that are the substance of the typestracts. “This visual ‘intentional’ concrete language knowingly engages with a Tantric discourse of coded language,” she tells us. These keys are intentionally present to unlock the pathway to the meditation that is latent in the typestract. The exhibition “presents a selection of those keys in relation to groupings of his work: moiré, thunderbolt vajra, yantra, chakrometers, chakra wheels, mantra, bija, tantric staircases etc.” [3]

Dom Sylvester was recognised in his lifetime as a significant exponent of the graphic values of the modern age, and this exhibition reminds us that his work is redolent of the contemplative values that are common to poetry and to spirituality, However, although he is also recognised, both nationally and internationally, as a theorist as well as an influential practitioner of concrete poetry, a critical description of his work, in general, has eluded commentators, collectors and curators alike. tantric poetries casts a radically new and elucidating light on an intensely productive decade. Dr Simpson has undoubtedly succeeded where others have struggled, proposing a possible spiritual route to a systematic schema of Dom Sylvester’s creative work of the decade, and to the living, poetic language with which he had engaged.

Installation view: the central mandala of the display. Photograph © Dom Sylvester Houédard; Courtesy Lisson Gallery

The Wider Ecumenism

.

However, some caution is needed. Dr Simpson has a perceptive grasp of the values of the language of concrete poetry, which emerged as a global, creative force in the post-WW2 decades. And her profound knowledge of Buddhism through years of practice and study in the New Kadampa Mahayana tradition has certainly enabled her to recognise and to decipher Dom Sylvester’s intuitive use of his Olivetti typewriter to communicate his comprehensive grasp of tantra. Thus the creative substance of this exhibition may validly be seen, in itself, as she claims, as a living transmission of the Buddha’s message to mankind.

But it should also be pointed out that Dom Sylvester’s extended vocation was dedicated to identifying a universal form of spirituality that is suitable for the modern era – a fact that does not in any way imply dissimilitude from the traditions to which he adhered. He coined the phrase ‘The Wider Ecumenism’ as a platform from which to express his thought. It is sometimes thought that ‘wider ecumenism’ – reflecting the meaning of ‘ecumenism’ as discussion between the different branches of Christianity – implies no more than to establish a dialogue between Catholicism and members of other faiths. But for Dom Sylvester it was about the rediscovery of the full meaning of universality and the act of being. To embrace truth, one does not ask, ‘is this the truth or is that the truth?’, one asks, ‘what is the truth in this?’, and ‘what is the truth in that?’.

Later in his life he found an illustration of a twelfth century biblical illumination: it illustrates Abraham, iconically sitting in the ‘A’ of Adam, which is the opening letter of The First Book of Chronicles. In Abraham’s lap are members of all three religious families descended from his progeny, Jews, Christians and Muslims. This, Dom Sylvester would explain, is the ecumenic norm of the monotheist traditions, a reality recognised by the Benedictines who copied the text of their Bible nine hundred years ago. He went on to explain:

(the ecumenic norm of the three families) would seem to offer a firm basis from which the Benedictine tradition can explore, as an integral area of monastic theology, the domestic economy by which God regulates His household in the most extended wider sense…beginning with the entire human race… [4]

This statement opens windows over at least three fields. One is the ecumenic norm mentioned by Dom Sylvester, that is, the unity of the traditions that recognise the source of all Being as One, absolute, but all-merciful God. The second is an understanding that ‘His household’ includes all the spiritual traditions that continue to exercise influence in the co-existent global environment of the contemporary world; these include the Vedic tradition and the many schools of living Buddhism. The third is that his understanding that the concerns of ‘the entire human race’ include the social, humanist, creative, scientific and economic activities of humanity in which the spiritual dimension is generally regarded to have only a subsidiary – if any – place, but which nevertheless, in the universality of truth are the recipients of God’s Mercy and Beneficence. Dom Sylvester engaged directly in dialogue with each sector at different times. To confine a critique of his work entirely within a Buddhist interpretation, or indeed any one belief-system, is therefore to miss one of the most dynamic aspects of his vision.

Environmentpoem: “On the enclosed leaf of our petition to time before the no act of un doing”, 1967. From a series of mixed media and laminate works (this one is two-sided) using natural materials gathered from the grounds of Prinknash Abbey. Photograph © Dom Sylvester Houédard; Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Dom Sylvester’s Legacy

.

Considering that, on one hand, the language of concrete poetry is obscure to many people, and on the other that a concern with spirituality is elusive in the modern world, one might assume that the graphic art of Dom Sylvester is not well received generally. And yet his work is proving to be of great interest to a younger generation of contemporary artists. His playful graphic work, executed with the greatest dexterity and skill, has a visionary quality that draws the eye and mind into its understated grasp of fragmented spaces. It has been suggested that he may in certain respects be comparable with William Blake.

But I would suggest, though very different in style, there may be more reason today to see his standing as comparable to that of Aubrey Beardsley. Both of them manipulated space, inventing a new vision, using a writing implement; both spoke graphically from the conscience of their time. And both were neglected for a time – one for his flight into obscenity, the other because he was religious. Towards the end of Dom Sylvester’s productive years, 1971–2, The Victoria & Albert Museum graphics department arranged a retrospective exhibition of his work. But today, almost half a century later, while the 1960s has increasingly attracted attention, Dom Sylvester remains inadequately represented in national collections. Is it too much to hope that Tate Britain or one of our other great galleries might like to take note of the significance of the Lisson Gallery’s current offering of Dom Sylvester’s work?

Dom Sylvester Dom Sylvester Houédard at the Signals Gallery in 1964. Photograph © Clay Perry courtesy England & Co Gallery

For more on Dom Sylvester, see Nicola Simpson’s article on his 1966 poem d-r-a-w-n-i-n-w-a-r-d in Beshara Magazine Issue 2 by clicking here.

For more on this exhibition, see the Lisson Gallery website.

Charles Verey is an artist and writer living in Gloucester. He is currently working with Jane Clark on a collection of Dom Sylvester’s late lectures: ‘The Kiss; Dom Sylvester Houédard’s Beshara Talks 1986–92’ (Beshara Publications, forthcoming 2020).

More News & Views

Book Review: ‘spinning pinwheels’

Gabriel Rosenstock rediscovers kokoro (heart) in a new book by the distinguished Indian poet K. Ramesh

The Kogi: More on Munekan Masha

Luci Attala talks about the recent visit of the Kogi Ambassador, José Manuel, to the UK, and the latest developments in her work with these remarkable Indigenous people

Book Review: ‘Is A River Alive?’ by Robert Macfarlane

Peter Huitson reviews a book which explores the living presence of diverse rivers around the world and their power to heal and transform

Introducing… ‘Many Beautiful Things’

Steve Scott presents a film on the extraordinary life and work of the Victorian artist and missionary, who set up a dialogue with the Sufi brotherhoods of Algeria

The Voice in the Circuitry

Peter Huitson collaborates with T.B. Schenck to explore the possibility of divine influence in AI

Book Review: ‘Winter Light’ by Douglas Penick

Peter Huitson reviews a book which celebrates creativity and deepening perspectives in old age

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Sources (click to open)

[1] Dom Sylvester Houédard, ‘Heathen Holiness’, in The Aylesford Review (3.3, Autumn 1960) p. 95.

[2] Nicola Simpson, ‘right mind-minding: the practice and transmission of Zen and Tantric Buddhist method pradtices in the poemobjects of Dom Sylvester Houédard, 1960–1975. (PhD Thesis)

[3] Nicola Simpson, dsh: tantric poetries (exhibition catalogue, click here

[4] Dom Sylvester Houédard, ‘Ibn ‘Arabi’s Contribution to the Wider Ecumenism’ in S. Hirtenstein and M. Tiernan (eds.), Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi, A Commemorative Volume (Element Books Ltd, 1993), p. 297.

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

1 Comment

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

Thank you Charles for this review and insight into the remarkable Dom Sylvester -a man for all times and a man of humility. Although we may not be able to travel to London at this time, the taste of this brilliant mind is clear and lasting.