A Thing of Beauty _|_ Issue 28, 2025

Transmission Across Cultures: The Islamic influence on European Architecture

Writer and art historian Diana Darke brings to light the largely unacknowledged influence of Islamic architecture and craftsmen on the iconic buildings of Europe

Transmission Across Cultures: The Islamic influence on European Architecture

Writer and art historian Diana Darke brings to light the largely unacknowledged influence of Islamic architecture and craftsmen on the iconic buildings of Europe

Diana Darke has spent decades living and travelling in the Middle East and has written widely on its art and culture. Her most recent books – Stealing from the Saracens (2020) [1] and Islamesque (2024) [2] – are highly acclaimed ground-breaking studies which trace the Arab and Islamic influence on Europe’s architectural heritage, from the rise of the earliest cathedrals in places like Pisa and Durham to Notre Dame in Paris and St Pauls in London. Through meticulous research, she shows how many of these great buildings, which continue to define our cultural identity today, were built by highly skilled Muslim craftsmen who were, in turn, drawing on the heritage of previous civilisations. She spoke to Jane Clark and Phoebe Ryrko by Zoom about how she came to embark upon this inspiring study of the interconnectedness of human culture.

Jane: In Stealing from the Saracens and Islamesque you argue that there has been a very significant transmission of knowledge and skill from the Islamic world into Europe which has not been fully acknowledged. You also open up wider questions about the validity of any culture making an exclusive claim to certain kinds of ideas and skills. What you show is that in art, in architecture, in mathematics and technology, there is a constant flow of transmission which is not limited by political and geographical boundaries, with each civilisation building upon the knowledge of the previous one.

But can we begin by asking you about your background? I know that you started out studying Arabic at Wadham College in Oxford. And that you bought a lovely old traditional house in Syria, whose renovation you describe in your book My House in Damascus.[3] Did you do this because of a pre-existing interest in Islamic architecture, or was it the trigger for what you went on to do?

Jane: In Stealing from the Saracens and Islamesque you argue that there has been a very significant transmission of knowledge and skill from the Islamic world into Europe which has not been fully acknowledged. You also open up wider questions about the validity of any culture making an exclusive claim to certain kinds of ideas and skills. What you show is that in art, in architecture, in mathematics and technology, there is a constant flow of transmission which is not limited by political and geographical boundaries, with each civilisation building upon the knowledge of the previous one.

Jane: In Stealing from the Saracens and Islamesque you argue that there has been a very significant transmission of knowledge and skill from the Islamic world into Europe which has not been fully acknowledged. You also open up wider questions about the validity of any culture making an exclusive claim to certain kinds of ideas and skills. What you show is that in art, in architecture, in mathematics and technology, there is a constant flow of transmission which is not limited by political and geographical boundaries, with each civilisation building upon the knowledge of the previous one.

But can we begin by asking you about your background? I know that you started out studying Arabic at Wadham College in Oxford. And that you bought a lovely old traditional house in Syria, whose renovation you describe in your book My House in Damascus.[3] Did you do this because of a pre-existing interest in Islamic architecture, or was it the trigger for what you went on to do?

Diana: My interest in the architectural aspect most definitely began with buying the house, and it was a not a planned thing at all. Basically, it happened because I was commissioned to write a detailed guidebook to Syria. So I travelled there in 2004 and 2005 and discovered quite by chance that it was possible to buy one of the Damascene Ottoman houses in the old city. I couldn’t believe it. I thought: What! This is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and I’m allowed to buy a chunk of it!

At university, I’d switched from German and Philosophy to Arabic because I very quickly realised when I got to Oxford that I wanted to do something completely new. I could have done Chinese or Japanese, or Sanskrit, but I chose Arabic because I had always been interested in the birthplace of civilisation – the Tigris and the Euphrates, the Nile Valley, all those very early archaeological sites where it all began. I thought that part of the world must be fascinating because of everything that has happened there.

I had no family connection to the Middle East whatsoever. We’d never been east of Greece, and I was brought up to believe that Greece and Rome were the source of all civilisation – that there was nothing of any particular significance beyond Europe. That was the norm in the education system in my day. So when I first travelled east of Greece to Turkey and Syria and Jordan and Palestine and Egypt – well, I really had my eyes opened to a whole new world.

Jane: You were living and working there, not just visiting as a tourist?

Diana: Yes, after university, I worked for GCHQ as an Arabic linguist specialist. They trained me up in modern Arabic because the university course was really about culture, it was not a language course. Then I went to work for a company in the Middle East which involved me doing a lot of travelling, and that was how I came to write guidebooks. I went on holiday to Turkey and thought: my goodness, what a wonderful country. Why has nobody written a guidebook to it? This was back in the 80s and there simply wasn’t anything for Western tourists.

I found a publisher who was interested, but at first it was just a hobby. I had my day job, and in the evenings worked on the guidebook and all my holidays became trips to Turkey. And that’s been the case ever since; all my holidays are research trips. The first book was a success, so I went on to write guidebooks to lots of Islamic countries: Dubai, Oman, Tunisia, Jordan, the Holy Land. Syria was one of the later ones.

Phoebe: So how did the renovation of your house in Damascus lead to the writing of the latest two books?

Diana: From the moment I bought the house, I was intrigued by all the patterns and the symbolism that I could see in the decorative features. It was a three-year restoration programme with a Syrian architect and a team of Syrian craftsmen, and it really deepened my interest in the art and architecture. So I went back into the academic world and did an MA in Islamic Art and Architecture at SOAS in London. The actual books on architecture didn’t begin till 2020. The first one, Stealing from the Saracens, was triggered by the fire at Notre Dame. I was watching the world’s reaction to the fire, and the French saying: our national identity is going up in flames. I thought: My goodness, don’t people realise that all these features that they’re calling ‘the French national identity’ actually came into Europe from the Islamic world? Nobody seemed to be aware of that.

I’d also just been on holiday to Cordova and Granada and noticed how the Islamic contribution – the 800 years of Arab civilisation in Spain – was kind of being pushed under the carpet and not openly acknowledged in a way that I found a little bit shocking. The combination of the two things made me think that there was room for a book on the subject, so I mentioned it to my publisher who basically said, yes, go for it.

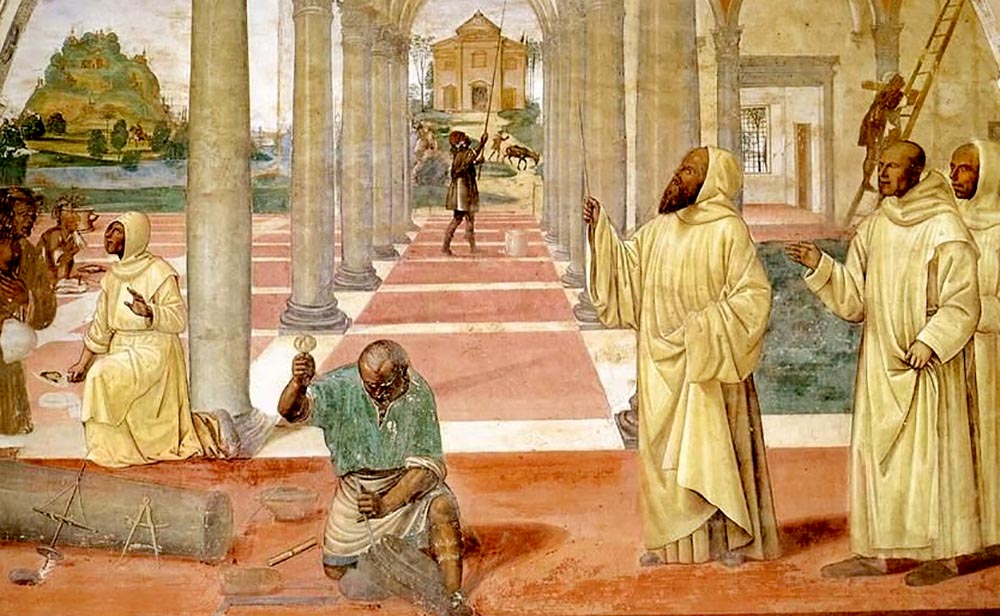

Above: The dome of the Selimiyye Mosque in Edirne, designed by the great Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan and completed in 1575 CE Below: The dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in London, completed in 1708 CE. Wren freely admitted his use of ‘Saracen’ vaulting. Photograph: B.O’Kane [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

Islamesque

.

Jane: One of the inspirations for your ideas, I think rather surprisingly for many people, is Christopher Wren, the builder of some of the most iconic buildings in the UK like St Paul’s Cathedral in London and the Sheldonian in Oxford.

Diana: Yes, Wren said more than 300 years ago, when he built St Pauls, that he had used Saracen vaulting in the dome, which is why we put a picture of that on the cover of the first book. And the reason that he used it, Wren tells us, was because it was the best technology around at the time. And that’s really what it all boils down to. If you are building a prestige project, sponsored by people who’ve got money – rulers, bishops, whoever – of course you’re going to go for the best, wherever it comes from. Wren said that he was building for eternity; he didn’t want to put up something shoddy that was going to fall down in 20 or 50 years. He also took the idea of the double dome from the mosques in Istanbul, though in St Paul’s he extended it to a triple dome. (For more on this, see Diana’s talk at the Wren 300 Symposium in 2023; video right or below.)

Video: Christopher Wren and the ‘Saracen’ Style, duration 23:23

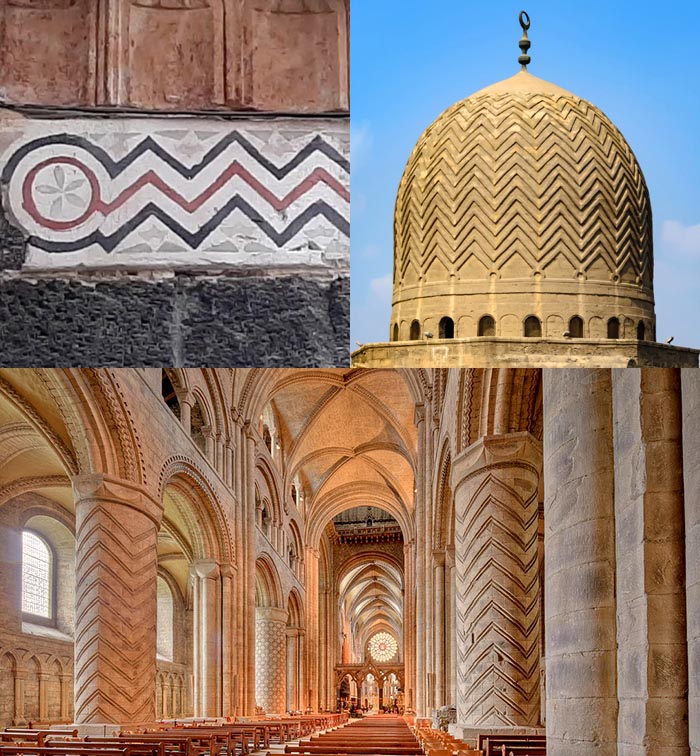

Jane: You point out that Wren was unusual in acknowledging the source of his work and how it has been inspired by mosques in Istanbul. He also perceived the influence of Islamic architecture in the great cathedrals of Europe and went so far as to say that what we call ‘Gothic’ should really be called Arab or Saracen architecture – ‘Saracen’ being the way in which Muslims were referred to at that time. This is the period you covered in your first book. But in the second book, you trace the influence back even further, to the period which preceded the Gothic, in buildings like the Leaning Tower and the Duomo in Pisa, or Durham Cathedral in the UK.

Diana: What my research made clear is that the year 1100 is the key year when art history books start to talk about a new style of architecture appearing in Europe. This was later called ‘Romanesque’ in the 19th century by a pair of French art historians because they saw it as a kind of miraculous revival of the glory of ancient Rome. But architecture doesn’t work like that. Nothing just pops out miraculously like some sort of virgin birth. That’s why I have coined the word ‘Islamesque’, because if we are going to put a label on something, we should at least call it something accurate.

I base my argument on timing and geography. In Spain, the 11th century marks the start of the collapse of the caliphate in Cordoba. The Arabs there were originally from Syria, of course – they were the last remnants of the Umayyad dynasty – but they were in Spain for 800 years. But from about 1030, Christian rulers in Latin Christendom started to retake territory in northern Spain. At the same time, in Muslim Sicily, where the Arabs had been for about 300 years, the Normans reconquered it in 1061. The Arabs in Sicily were mainly from Egypt, so they had a slightly different style to that of Spain.

At that time, Arabi culture was at its absolute peak. It was 200 years ahead of Europe. The ordinary people, like craftsmen, were literate and numerate, and they had a very sophisticated understanding of geometry and algebra. They were building ribbed vaults to support stone domes hundreds of years before Europe was able to do any such thing. But politically, their world was collapsing – at least in the Western regions of the Empire – and the Latin Christendom star was on the rise. And of course, the new Christian rulers coming in, who wished to show off their wealth and power, wanted the best, just as Christopher Wren did. And who was going to be able to build the best monasteries, the best castles, the best cathedrals? It was the Muslims, as they were the only people who had the knowledge to be able to construct what seemed like miraculous buildings to Europeans.

Jane: You show how these new buildings were not only inspired by what the Christian conquerors saw in Spain and Sicily but were actually built by Muslim craftsmen who were brought in as kind of migrant workers.

Diana: Yes, the only way that these buildings could have been created was by top Muslim craftsmen who brought their skills into Europe. They not only masterminded the construction of the ribbed vaulting and stone domes; they also brought in all their decorative styles, which you then start to see transferred from mosques and Islamic palaces into European cathedrals, monasteries and castles. In the book, I track these quite methodically, showing how the styles and the patterns, the ornamental designs, are found in mosques and secular palaces well before they appear in Romanesque architecture and how they move from Muslim Spain and Sicily and to some extent across North Africa from Egypt.

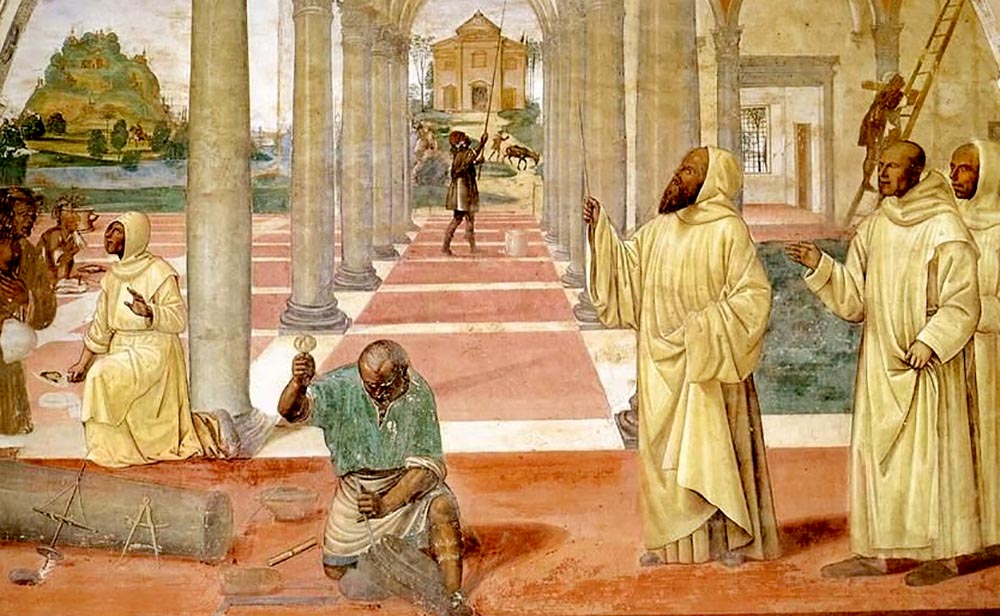

Jane: You have this lovely picture on the front of Islamesque of a mural where Moorish-looking builders are actually depicted, which we have used for the banner of this interview.

Diana: I was so pleased to find that. It’s a Renaissance fresco showing Saint Benedict founding 12 monasteries. According to a stonemason friend of mine, he can tell, just from the way the scaffolding is done, that the painter back in the early 1500s was working from an actual building site. Obviously, Saint Benedict is fantasised because he lived several centuries earlier, but the actual building site and the craftsmen would have been as he saw them. The mason, the carpenter and the people consulting the maps are all look as if they’re not Christians.

Arches. Above left: The ablution fountain in the courtyard of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, completed about 715 CE. Above right: The interior of the Cordova Mosque in Spain, completed in 785 CE. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons. Below: the bell tower of the Leaning Tower of Pisa in Italy, whose construction began in 1172CE. Photograph: Wikimedia Commons

Transmission Across Cultures

.

Phoebe: You mention that the Muslims had themselves built their knowledge upon what they received from the Byzantine civilisation, which was of course Christian.

Diana: Yes, when Islam came out of the Arabian Peninsula in the seventh century, they became masters of a huge empire under the Umayyads. They decided to make Damascus their first capital, but they didn’t have any highly skilled craftsmen who were able to create magnificent buildings. So they employed the top craftsmen of their day, who were Byzantine Christians. The mosaics of the great Umayyad Mosque, which still stands at the heart of the old city, were created by these Byzantine mosaicists, who instead of creating the saints and biblical scenes we find in the Eastern churches, produced visions of the Islamic Paradise – fantasised trees, gardens and rivers.

A master craftsman can turn their hand to whatever is required. It was the same in Spain when the Christian rulers took over. The Muslim craftsmen, who were at the top of their game, were equally able to turn their hand to what the new masters wanted. They still had to feed their families, and they also wanted to carry on practising their profession – they had skills which had been honed over many, many generations, tending to be passed down through families. The most prominent of these was stonemasonry, and the knowledge of geometry and mathematics which allowed these great structures to hold up and not fall down. But they also excelled at ironwork, woodwork and glass work.

The Muslim craftsmen had not been able to carve sculptures of people in Islamic religious buildings, but they were perfectly okay in secular settings. The caliph’s palaces would have had many statues and images of people and fantastical beasts and elements like that. So the craftsmen simply transferred these skills to the buildings the Christians were commissioning.

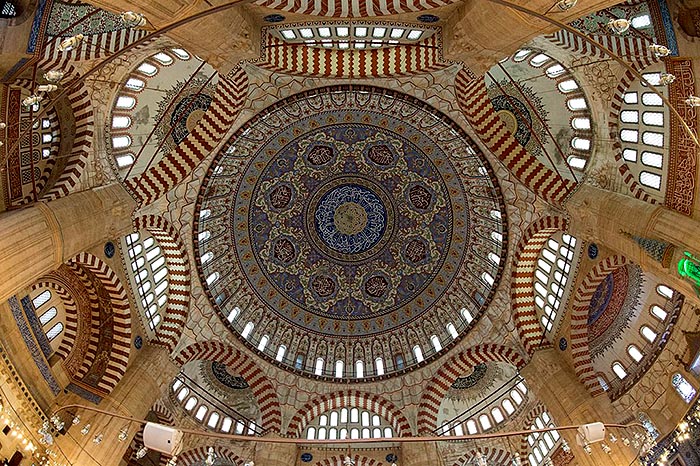

Jane: You also trace the history of the zig-zag pattern which you found in your house in Damascus back to ancient Egypt. You show how, as a motif, it has travelled through thousands of years of history to finally become one of the most distinctive elements of Romanesque architecture.

Diana: It was the zig-zag pattern that really started me off on this journey. I have a very fine example of it in my house in Damascus and was intrigued by it. I eventually came to see that it has been based upon the Egyptian hieroglyph for water and represents a spring. I then traced the motif through the temples and tombs of various Egyptian dynasties into the churches and monasteries of the Christian Copts who succeeded them, and finally into the repertoire of early Islamic architecture in Syria. Within the Islamic world, it was perhaps most prevalent in the architecture of the Fatimids, who ruled Egypt for about 200 years. It probably came into Europe via Sicily – you can see zig-zags all over Palermo – and the Normans. That is why it dominates the decoration of Durham Cathedral, which I have come to call ‘the English zig-zag capital’.

Zig-zags. Above left: Zig-zag pattern in Diana’s house in Damascus. Above right: Dome of the Bab Zuwayla Mosque in Egypt, completed in 1092CE. Photograph: Hedaya [/] / Alamy Stock Photo Below: The interior of Durham Cathedral in UK, completed in 1096, showing many features of ‘Islamesque’ – zig-zag patterns on the columns, ribbed vaulting in the nave and pointed arches. Image via Wikimedia Commons

The Master Builders

.

Jane: On what basis do you think these Muslim craftsmen came into Europe. Were they prisoners captured in the conquest, or paid workers?

Diana: This is an intriguing question which I am still looking into. I think it was a bit of both. The evidence for their presence is quite scant. In Britain, for instance, there are the Arabic numerals carved into the rafters of Salisbury Cathedral, and also in Wells Cathedral, on the west front, on the statuary. It is fascinating to find these centuries before Arabic numerals were in use in this country. There are also one or two documented cases of a crusader knight bringing home Saracen craftsmen. One of these settled in Staffordshire, I think it was. And there is an oral tradition which I mention in the book that Durham was built by Moorish masons brought back from the Holy Land after the First Crusade. But I think more and more is going to come out now that we have started to look for it.

Phoebe: And how long was it, do you think, before the construction work was taken on by native craftsmen?

Diana: Well, we know that even as late as 1492, when Ferdinand and Isabella completed the Reconquista and took over the Jafariya Palace in Saragossa, they appointed a Muslim master builder for life to look after all the palaces in Aragon. Why would they do that? Well, I think it was simply because he was the best – better than any equivalent Christian even at the time.

My initial research shows that it took between 200 and 300 years for the skills to pass across to equivalent Christian craftsmen. And one of the reasons that it happened was because of the guilds. Craftsmen’s guilds had been a feature of the Islamic world; the Byzantine world also had them. But in the Islamic world, the guilds were open to everybody. You could be a Muslim, a Christian, a Jew, it didn’t matter; the important thing was that you were good at your craft. But as the Christians started to acquire the skills from the Muslims, they set up their own guilds, which then excluded Muslims and Jews. You could only join them if you were a Christian.

In the same vein, it’s very interesting that there are no names at all for the craftsmen who built the early Romanesque cathedrals. The only names given, again and again, are of the bishop or the king who sponsored them. Then suddenly as you start to move into Gothic, the masons are named. My theory is that the minute they think they can attribute it to a Christian, lo and behold, the names start to appear.

Although the situation may not be as straightforward as it seems at first glance, because in the course of my research I discovered that names can be very fluid. In Sicily, for example, there are records which say ‘Roger, who was once Ahmed’ because somebody converted, or Christians called Muhammad because people intermarried. At Canterbury, William of Sens is credited with creating the ribbed vaulting, and this is understood to be the first example of early Gothic in England. The Romanesque nave ceiling burnt down and there wasn’t anybody in this country who could do it, so they had to bring him across from France. But just because he was called William doesn’t mean he was Christian – that he was not originally a Muslim or somebody schooled in the Islamic tradition. As with foreign builders today with some unpronounceable name, people were often given a local nickname or they adopted a more conventional name to fit in.

Decoration. Left: Interior of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, showing the mosaics created by Byzantine craftsmen and Syrian glass. Photograph: Kevin Lang [/] / Alamy Stock Photo. Right top: A fantastical griffin found at the royal palace of Shabwa in the Yemen (third century) where the civilisation of the Hadramaut had a long tradition of stone-working and sculpture. Photograph: Jidan via Wikimedia Commons. Right bottom: Zoomorphic animal musicians carved into the capital of a column in the crypt at Canterbury Cathedral (late 11th century), said to be first appearance of such beasts in England. Photograph: Angelo Hornak [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

The Tendency to Monopoly

.

Jane: So do you think that the tendency not to acknowledge the Islamic source of arts and technologies goes right back to the original time of transmission?

Diana: I would certainly say that the Christian desire to have a monopoly on things, or to appropriate things without acknowledgement, is a pattern that I have come across more than once in my research. Another example is Venice and Murano glass. When the Latin Crusaders took over parts of Syria, they discovered how wonderful Syrian glass was. Syria was the world leader in glass at that time, and the raw materials to make it and the colours they created were way, way superior to anything else around. The Christians wanted to use this wonderful glass in their stained-glass windows, so it was shipped across in large quantities out of places like Antioch in Crusader ships. This, incidentally, is one of the things I noted in the fire at Notre Dame, where the windows are made from this special glass. It’s very, very strong, very resilient, and I’m personally convinced that this is the main reason that it didn’t just shatter and break in the extraordinary heat of the inferno.

So, what happened in Syria is that in 1401 Tamerlane completely destroyed Damascus and ran off with all the craftsmen. Suddenly the glass industry there was dead, just like that. But the Venetians had very cleverly been trading with that part of the world and they understood the value of this glass. They acquired the recipes for it, and probably also brought in a few of the craftsmen as well. In whatever way, they learnt the secrets of its manufacture and then kept it very exclusively on Murano Island. People weren’t even allowed to go to and fro from the island so that they, the Venetians, could retain control of a complete monopoly. But even as late as the 15th century, the Venetian recipes for glass were specifying that it used cinders from Syria.

Jane: One of the questions that we wanted to ask you is why there is such denial of the Islamic influence in European culture. Given the extent of it, it seems reasonably extraordinary. It happens in areas other than architecture. In literature, for example, people are very reluctant to admit the influence of the muwashshahat – the song forms which were common to all the cultures of the Mediterranean – on things like early forms of the sonnet. But what you’ve said perhaps indicates that this tendency towards denial links to the whole phenomenon of colonialisation. The Europeans always wanted a monopoly on trade. They were never very happy with open exchange.

Diana: Yes, that has been a trend that I’ve noticed – that basically Muslim societies were very inclusive and Christian ones were very exclusive. Another example is the way that the Benedictines controlled the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela in Southern France and Spain. The Benedictines became very rich around that key 1100 date and started to build a series of cathedrals and monasteries on the routes to Compostela from Cluny and Paris. There were many routes, and they were all studded with stopovers built and controlled by the Benedictines to encourage the pilgrimage trade. Everybody had to stay in these places and that of course made the church richer and richer. It is kind of ironic that it is in these buildings that the Islamic influence first starts to show.

The facade of Notre Dame in Paris, with labels showing the features borrowed from Islamic architecture. (1) twin towers flanking monumental pointed arch entrance, (2) twin windows, (3) delicate tracery, (4) arcades of trefoil arches, (5) pointed arches, (6) double arcade. Photograph: via Wiki Media Commons, labels from Stealing from the Saracens, p. 362

Hiding in Plain Sight

.

Jane: An element of both books which I myself very much appreciate is that you include pictures of buildings with little labels pointing out various features which show the influence of Islamic architecture on buildings that are still very much part of our surroundings. Things like ribbed vaulting, pointed arches, twin windows, etc., in churches and cathedrals. Or on Romanesque buildings, which in the UK we tend to call ‘Norman’, the zig-zag patterns and carvings of beasts and foliage on so many church doors and windows. Once these things are pointed out, it is almost impossible not to see them everywhere.

Diana: Absolutely. The evidence is all around us. I live part of the year in Kent and my local cathedral is Canterbury. Before I was interested in all of this, I would maybe glance up at the roof and the tower, but all the focus when I went round the cathedral was upon the Thomas Becket stuff, the corona, Canterbury as a site of pilgrimage. So when I went recently, I wasn’t really expecting to find so much Romanesque stuff. But even looking just on the outside, it took my breath away. I thought: my goodness! There are all those rows of blind niches, blind arcades, zigzags, spirals, slender columns, little twin windows and multi-lobed arches. It was all there, hiding in plain sight all along, and I didn’t know what I was looking at.

Phoebe: I wonder how the awareness of what you are bringing will influence how Europeans see themselves. How could this new understanding of Notre Dame, for instance, influence French national identity, as they wrestle with the fact that their population is actually very diverse? In this sense your work speaks very profoundly to this time, it seems.

Diana: Unfortunately, all the interest in these books seems to be coming from the Islamic world, because people there can see the connections I am making straight away. They are being translated into Arabic and Turkish, but so far there has not been a single nibble from any publisher wanting to put them into French or German or Italian or Spanish. I’m rather hoping, though, that the word ‘Islamesque’, which I’ve made up in direct challenge to the concept of Romanesque, will enter the English language as a new word.

Phoebe: Are there not French Muslims who would want to translate the books into French?

Diana: It’s funny you should say that, because I’ve been in touch with the most wonderful guy who is a French Muslim who was employed to work on the renovation after the fire of Notre Dame. I quote him at the end of Islamesque. He is a top craftsmen because the restoration has been a classic case of people wanting to use the best. They only had five years to finish it, and the thing about really good craftsmen is that they work very fast, much faster and more efficiently than mediocre craftsmen. Everyone working on the building had to sign an agreement to keep a very low profile and not to speak to the press. It was only through a chance contact that I managed to meet this guy, who was unusually prepared to talk after the work was completed.

And what he talked about was his joy as a Muslim in helping rebuild the cathedral. It made him feel proud. I personally think his family was probably one of the Muslim families that settled in Switzerland in medieval times because he comes from that area of France. In the book I look at these very early communities, which even before the year 1100 were clearly settled in France, or in Germany, Switzerland, Italy or Spain. There’s not a great deal known, but almost every week now it seems that some new discovery is made about the way that the different religious communities were living together at that time.

Jane: So just as last question: what is the state of craftsmanship in the Islamic world right now? I ask you because we’ve had some involvement with the King’s School of Traditional Arts in London, which is concerned with preserving knowledge that has been lost in many places because of war, or colonialism, or modernisation, or whatever. When you renovated your house in Syria, did you find craftsmen there with the required traditional knowledge?

Diana: Yes, absolutely. I was so impressed with the skills of the people there. They still do things by feel, from kind of instinct. It is almost as if it is in their DNA. I think the real difference in that part of the world is that the skills are still passed down through the generations. There are still a couple of Syrian glassblowers in Damascus and stonemasonry continues to be strong. I have a friend who has a house in Aleppo – a courtyard house – which was destroyed in the Russian bombing, and he was able to find local craftsmen who could restore it using traditional techniques. The problem is that these people are not valued in the way that they should be. Their pay isn’t great, because economically that part of the world hasn’t got much money.

There’s been some bad restoration work in the old city of Damascus, but I was very, very conscientious with my own house because I wanted it to look old. It’s full of defects that reflect its history. Old Damascus has been destroyed multiple times across history, so each side of the courtyard is from a different century. It’s a beautiful mix of 17th, 18th and 19th century styles that all blend together and represent how the city has overcome all the vicissitudes of history that have been thrown its way – war, earthquakes, fire – and still survived.

Jane: Diana, thank you for talking to us about this fascinating subject. It has certainly made us look at our cities and churches in a new way.

This video of the book launch of Islamesque gives more information about Diana’s insights.

Video: Book Launch of ‘Islamesque: The Forgotten Craftsmen Who Built Europe’s Medieval Monuments’; duration 43:08

Or for a longer and more detailed interview (duration 1:04:18), click here [/].

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: Detail of a fresco St Benedict Founds 12 Monasteries painted by Il Sodoma in about 1505. Image: via Wikimedia Commons.

Inset: Diana Darke.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] DIANA DARKE, Stealing from the Saracens (Hurst & Company, 2020) https://www.hurstpublishers.com/book/stealing-from-the-saracens/

[2] DIANA DARKE, Islamesque, (Hurst & Company, 2024) https://www.hurstpublishers.com/book/islamesque/

[3] DIANA DARKE, My House in Damascus (Haus Publishing, 2016) https://www.hauspublishing.com/product/my-house-in-damascus/

The text of this article has a Creative Commons Licence BY-NC-ND 4.0 [/]. We are not able to give permission for reproduction of the illustrations; details of their sources are given in the captions.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Christopher Wren and the ‘Saracen’ Style, duration 23:23

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

The Cosmos in Stone: The Ascent of the Soul

Tom Bree correlates the meaning embodied in the geometry of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and Wells Cathedral in Southern England

A Thing of Beauty…

David Apthorpe extols the geometry and decoration in Sinan’s small masterpiece, the Sokollu Mehmet Pasha Mosque in Istanbul

Keith Critchlow: A Life Well Lived

Richard Twinch pays tribute to the teacher and sacred geometer who died on April 8th 2020

A New Architectural Language for Islam

The inclusive vision of Glenn Murcutt’s Australian Islamic Centre

READERS’ COMMENTS

Very interesting indee. it show how the idea of nationalism is not valid in terms of idenity, which we know. It is the culture and skills of the peole that is and these are so fluid that they weave a very entangled web even then. Nothing really can be claimed as one’s own or one’s country’s own.Iit all comes as an old – new beginnig, each time in each age and in each epoch.

What a fascinating and illuminating article. I’m off to order ‘Islamesque’…

I absolutely LOVED this article! I am English, lived in Italy for 26 years, but for some reason have a passionate love for the Middle East. I have seen and loved the connection between Islamic art and culture and the “West” for a long time. For me, it illustrates so well the ultimate truth that we all are one. I like to think of us all in our differences as separate cells in the body of humanity. Difference is interesting and complementary, enriching and enlightening. Thank you for this.

Fascinating interview, which I very much enjoyed, especially the video of Diana’s lecture. Many thanks.

I was particularly intrigued by Diana’s comment about Muslim culture being inclusive where Christian culture was exclusive. It is a shame that in some ways the poles have been reversed in the last few centuries.

I was particularly intrigued by Diana’s comment about Muslim culture being inclusive where Christian culture was exclusive. It is a shame that in some ways the poles have been reversed in the last few centuries.

Thanks you for shedding light on the Islamic influence on European architecture. Her article uncovers an unacknowledged impact on iconic landmarks in Europe, while also highlighting the continuous cultural exchange between civilizations.

A friend’s recent article touched onsome of the same themes: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brain-behavior-and-beauty/202504/the-rise-flower-and-fall-of-a-renaissance

I am just writing about St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall, Orkney. Wikipedia says ‘The Romanesque cathedral begun in 1137 has fine examples of Norman architecture, attributed to English masons who may have worked on Durham Cathedral. The masonry uses red sandstone quarried near Kirkwall and yellow sandstone from the island of Eday, often in alternating courses or in a chequerboard pattern to give a polychrome effect.’ Well, in addition to the ‘Islamesque’ ribbed vaults the chequerboard pattern of the doorways (see image in Wikipedia) is reminiscent of Cordova mosque.