A Thing of Beauty _|_ Issue 11, 2019

A Thing of Beauty…

David Hyams describes the creation of a new ark for the Synagogue in Oxford, UK

A Thing of Beauty…

David Hyams describes the creation of a new ark for the Synagogue in Oxford,

UK

In 2015 the Oxford Jewish Community decided that they needed a new ark. This is the large cabinet that accommodates the hand written scrolls of the Five Books of Moses which are regularly read out during services and form the central focus of the synagogue space. So they commissioned the distinguished architect Niall McLaughlin [/] to design it. McLaughlin is well known for his work for Oxford University, the London Natural History Museum and especially for his stunning Bishop Edward King Chapel at Cuddesden [/].

Facing a room full of community members for the first time, he began by asking: “What does ‘The Word’ mean in Judaism?” Coming from the Christian tradition, the question was related to his understanding of the New Testament Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God.”

It took a few moments for the audience to find the words to explain that ‘The Word’ as it is used in the Christian Bible – to denote the active rational and spiritual principle of the universe – is not discussed to any great extent in Judaism. It featured in the work of the first-century Hellenistic Jewish philosopher, Philo of Alexandria [/], and modern scholars have detected the influence of Sufi writers such as Ibn ʿArabi [/] – who certainly described many aspects of ‘The Word’ – in the late thirteenth century on the Jewish mystics of the time. Acknowledging these exceptions, the answer to the architect’s question was probably “not much” when ‘The Word’ is taken in the Christian sense, but “everything” when taken in the Jewish sense.

The Mishneh Torah is one of the most famous commentaries, written by the great Andalusian scholar Maimonides c.1180 CE. This lovely copy, with the illumination showing a man carrying a Torah scroll, was produced in Spain or Italy before 1351. Jewish National and University Library of Israel (MS. HEB. 4*1193). Photograph: via Wikimedia Commons

‘The Word’ in Judaism

..

Jews traditionally understand the Word of God as referring to the Ten Commandments inscribed by Moses under God’s instruction on two blocks of stone at Mount Sinai. The Commandments point to a vast hinterland of meaning. God’s Word, we are told, does not consist only of the revelation at Mount Sinai, described in Exodus XXIV, nor the entirety of the Five Books of Moses, nor even the whole of the Jewish Bible. ‘The Word’ in Judaism also encompasses the oral tradition and all the divinely-inspired rabbinical commentaries around these texts, handed down through the ages and continuously added to up to the present day. All of this is known as Torah – a Hebrew word meaning ‘instruction’ or ‘teaching’. It is sometimes translated as ‘law’ but there is a separate term, halacha, which describes the strictly legal aspect.

There are those who take the words of the original biblical text as literally sacrosanct, and there are others who insist that it is up to each generation to reinterpret the text in the light of current conditions. This range of interpretations has created a variety of denominations within Judaism, as it has in other religions. Those who follow Kabbalistic traditions, for instance, put great emphasis on the esoteric significance of particular sentences, words and individual letters as they appear in the Torah. They are held to be sacred and deeply symbolic. There is also a tradition of great respect for exceptional scholars – men and women – who have devoted themselves to a life-long study of the Jewish Bible and its commentaries.

Theology in the Christian sense barely exists in Judaism, as the nature of God is not controversial. Jews believe that God is the unique Being, an indivisible Unity, who is eternal, omnipresent, essentially good and loving, fair and just, omniscient, omnipotent. He is transcendent though also intervening in worldly affairs, and personally approachable though essentially unknowable. On the other hand, the rules governing acts of observance and avoidance in everyday life and in ritual practices have been the subject of continuous discussion and argument. In Judaism, awareness of God is closely tied to detailed observances, and people show their love for God by obedience to the instructions found in the many commentaries on the Torah. The minutiae of these instructions, covering every aspect of life, potentially give those who follow them constant reminders of the presence of God throughout their waking day. It has been said that, whereas Christianity is a religion of believing, Judaism is a religion of doing.

In another sense, the term ‘Torah’ is also used to denote the Five Books of Moses alone. This is the text meticulously handwritten by quill on parchment and wrapped around two wooden spindles in a Torah scroll. It is these scrolls that are kept in the synagogue ark. They are held in great respect, though they are not objects of worship. The cabinet in which they are kept is similarly respected. The English term ‘ark’ links today’s cabinet with the casket kept in the holiest part of the tented temple– as the Children of Israel wandered the Sinai desert after their escape from slavery in Egypt.

None of this was discussed at that initial design meeting for the ark project, but many of those in the room were delighted that Niall McLaughlin, rather than bringing the nuts and bolts of construction into the discussion, had begun the design project from an appropriate level, by invoking the significance and purpose of the ark.

The ‘everlasting light’ above the ark, and the words ‘Know before Whom you stand’. Photograph: Alison Ryde

The Ark in the Synagogue

.

Within the Oxford Synagogue, the ark is located centrally on a raised platform against the east wall, which is the wall that symbolically faces Jerusalem. It is free-standing, rather than built into the masonry as it is in many synagogues. In front of it, on a lower platform, stands a large reading desk. Above the ark, the ‘everlasting light’ is mounted on the clear wood facia along with the Hebrew inscription “Know before Whom you stand”. Higher up still, on white painted boards, are the initial words of each of the Ten Commandments, surmounted by a stylised symbol of the two tablets of stone or maybe a bird of the spirit. Inside the ark, the Torah scrolls are decked out in bright, embroidered covers and topped with silver ornaments.

At the weekly Saturday service, a Torah scroll is taken with ceremony from the ark and, having made a circuit of the synagogue, is placed on the large reading desk. The coverings of the scroll are removed, and a portion of it read before it is re-covered and returned to the ark. Whoever is leading the service will normally stand at the reading desk. After some discussion within the congregation, it was agreed to renovate the two platforms with their steps and handrails at the same time as making the new ark, and to replace the reading desk and associated seating. So the project expanded to embrace the renewal of the liturgical heart of the synagogue. It was all made possible by many donations, large and small, from members, past members and students, Jewish funding bodies and local Christian and Buddhist communities.

The ark, one or two raised platforms, the reading desk and the continuously burning light are features of most synagogues. In more traditional Jewish denominations, women sit completely separated from men, often behind a high partition or a curtain, while the service is conducted by men. In Oxford, this screen has been reduced to a symbolic plank. In Progressive services women and men sit together and take part equally in leading the service.

The Oxford Jewish community is very unusual, if not unique, in providing space for services of more than one Jewish denomination to take place separately at the same time on a typical Saturday morning. Whichever denomination has the larger congregation on any particular day gets to use the main prayer space. A consequence of this is that the community does not engage a rabbi, who would necessarily be attached to a single denomination, and this in turn means that there are no sermons and no need for a pulpit within the synagogue.

A view of the closed ark, plus the new reading desk and seating. Photograph: Robin Furlong [/]

The Pattern of Prayer

.

Niall McLaughlin’s design proposal forms the basis of the ark that has been built, although he became less involved in the project as it progressed. His ark is a simple, well-proportioned, rectangular cabinet, for which he proposed a wood finish – the final choice was walnut – decorated with a repetitive pattern of small geometric figures in relief.

He suggested that the surface patterning of the ark could be generated using the process developed by Ernst Chladni [/] in the eighteenth and nineteeth centuries. Chladni was a German physicist and musician who demonstrated that sophisticated geometric patterns could be formed using a violin bow to vibrate a metal plate on which small granules, such as iron filings, had been scattered. McLaughlin’s proposal was that the patterns on the ark could be produced in a similar manner by the sound of the congregation in prayer. This was a wonderful idea, but it was far from clear how it could practically be achieved.

The architect’s drawings were eventually passed to Robin Furlong, a master cabinetmaker, who was engaged to make the final piece. An internet search then produced a photograph of Professor Jim Woodhouse of Cambridge University demonstrating the Chladni approach. When contacted, he was extremely helpful and generous with his time. Professor Woodhouse specialises in vibrations of all types: in complex structures, earthquakes, musical instruments and squeaking brakes.

The author and Professor Woodhouse experimenting with the Chladni method in Cambridge Engineering Department. Photograph: community ark group member.

When community members visited him at the Department of Engineering in Cambridge, they took along several sound recordings of congregants singing verses from the liturgy. But when he demonstrated the Chladni procedure in the laboratory, it was immediately clear that there was a problem. The method only produces a definite geometric form from a clear pure tone: the higher the frequency, the more complex the pattern. The individual human voice, with its multiple tones and ornamentation, was not going to produce a usable pattern, the sound of a congregation singing even less so.

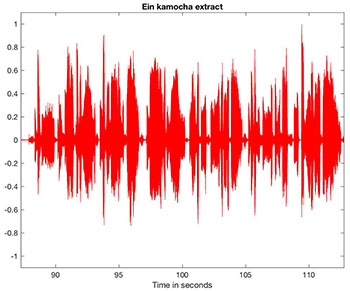

However, Professor Woodhouse then demonstrated the simplest of computer visualisations of several phrases of sung prayer. The plot below, on the left, shows a simple spectrogram with frequency (musical pitch) plotted vertically, against time plotted horizontally.

Spectrogram of the congregation singing, showing frequency (pitch) on the vertical azis and time on the horizontal axis. Courtesy Professor Jim Woodhouse

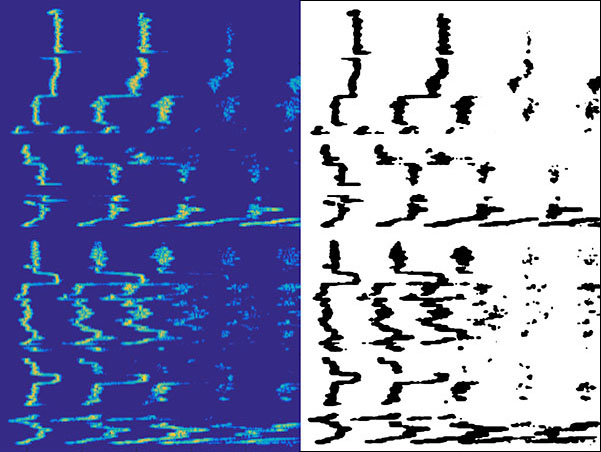

The same recording is processed in a different way in the figure on the right. In this, time runs vertically from the bottom up and frequency runs horizontally from left to right. The colours represent volume; the warmer the colour, the louder the volume. The vertical line of figures on the left of the image is the principal melody. It moves from left to right with the tune, stopping and starting with the singer’s articulation of the words. The figures that spread further to right are the harmonics generated by the human voice. The breaks and twisting shapes reflect the singer’s ornamentation, glides between notes and vibrato.

Alternative display of the spectogram which was used for the final pattern. Left: the full version showing time on the vertical axis and frequency on the horizontal. Right: the simplified imager which was projected onto the wood for carving. Courtesy Professor Jim Woodhouse

This method seemed to provide exactly the kind of visual effect we wanted. The phrases finally selected were those that produced the most satisfying visual patterns, which also turned out to be those sung when the doors of the ark are opened and closed each week for the Torah scroll to be taken out for reading. The first of these was applied to the doors of the ark’s main compartment, the second to the adjoining outer panels. Each pattern also features on one of the ends of the ark where doors give access to storage. The size and shape of the patterns were adjusted slightly to fit the panel size, and some patterns were reversed vertically or horizontally for visual effect. The process involved enlarging the final black and white images to full size and scanning them into a computerised router, which then cut the pattern into the walnut facing panels of the ark at a uniform depth.

The planks of walnut laid out in Robin Furlong’s workshop. Photograph: Robin Furlong [/]

The Effect of the Ark

.

The new ark project has brought to light a stream of differences of approach between church and synagogue design in all sorts of subtle and detailed areas, which neither the architect nor the client committee had previously considered. It was very much a process of discovery for all concerned, in which subliminal understandings of what makes a good synagogue have been slowly revealed. It has also uncovered ways in which the Oxford building and the expectations of the community differed from synagogues elsewhere.

The new ark was consecrated at a ceremony which marked the 175th anniversary of the founding of the current Jewish community in Oxford. Jews are known to have come to England with William the Conqueror and there was a thriving community in Oxford in the medieval period. All Jews were expelled from England by Edward I in 1290 and readmitted by Oliver Cromwell in 1656. From that time on, a small community has lived in Oxford, particularly after 1871 when an Act of Parliament permitted Jewish academics to take up full membership of the University. The congregation has had a number of homes over the years, but it was not until after 1960 that it was sufficiently established to support the construction of the present Jewish Centre in 1973–4. The Centre has been significantly enlarged since then.

The new ark has met with warm approval by community members and visitors alike. The symbolism of the pattern generated from the appropriate phrases of the liturgy is so simple and direct that it has great appeal. There is also much appreciation for the quality of the craftsmanship. The design of the ark and its decorative pattern fell into place almost effortlessly in a way that was obvious and required no struggle – just following steps that seemed clearly laid out. It may well be that ‘design’ is not even the word for this process. Designing the platform seating, which also displays the Torah covers when removed, was much more demanding. Others may judge whether the result is inspiring, as the brief stipulated. But what is certain is that the quality of the whole of the central area of the prayer space has been lifted.

So what is it about this overall design which is right for this particular Jewish community? It probably has to do with lighting, colour, warmth and the natural wood finish, as well as the avoidance of un-Jewish features such as cruciform design details. In addition, a sense of openness brings those leading the service close to all parts of the congregation.

So, it is hoped that ‘The Word’, in its Jewish sense, has been properly honoured and beautifully served by its new ark.

The author with Professor Woodhouse before the newly installed ark in Oxford. Professor Woodhous was able to trace the tune from the pattern as the relevant phrase was sung for him. Photograph courtesy Jim Woodhouse.

Image Sources (click to open)

The Ark in the Oxford synagogue, showing the Torah scrolls. Photograph: Alison Ryde.

Other Sources (click to open)

MARTIN GOODMAN: A History of Judaism. Allen Lane 2017.

DAVID M. LEWIS: The Jews of Oxford. The Oxford Jewish Congregation 1992.

David Hyams is a retired architect and designer. He is a member of the Oxford community and, along with others, was an active participant in the Ark project

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

A Caravan on a Spiritual Silk Road

Warren Kenton talks about the ancient Jewish tradition of Kabbalah and what it can teach us in the present day

Tell Them What We Have Learned Here…

Martha Cass writes about a remarkable group of 20th-century philosophers, known as the ‘death-cell philosophers’

A New Architectural Language for Islam

The inclusive vision of Glenn Murcutt’s Australian Islamic Centre

A Thing of Beauty…

Jane Clark contemplates the Chagall Peace Window and the Meditation Room in the United Nations building, New York

READERS’ COMMENTS

Hi. Thank you for this article. I edit a Buddhist magazine, Many Roads for Bodhicharya. Can I have permission to reproduce this or part of this article with a link to the magazine in the latest edition of Many Roads?

Thank you.

Dear Albert, Thanks for your message and my apologies the time it has taken me to reply to you. Yes it is possible. Can you write to me on my Magazine email to discuss further? jane.clark@besharamagazine.org

I could not resist commenting. Very well written!

I must appreciate the way you have expressed your feelings through your blog!

Do you have an email address for David Hyams?

Thank you for Sharing good quality article. it’s more useful.

You post is appreciateable and i like the blog’s design styling ….

your post is full of informational content, Awesome!

You post is appreciable! if you need super nice portable paper bags that look premium and can be fully customize, this factory is legit top pick!