A Thing of Beauty…

Jane Carroll visits Frank Lloyd Wrights’s masterpiece, Fallingwater

A Thing of Beauty…

Jane Carroll Towns visits Frank Lloyd Wrights’s masterpiece, Fallingwater

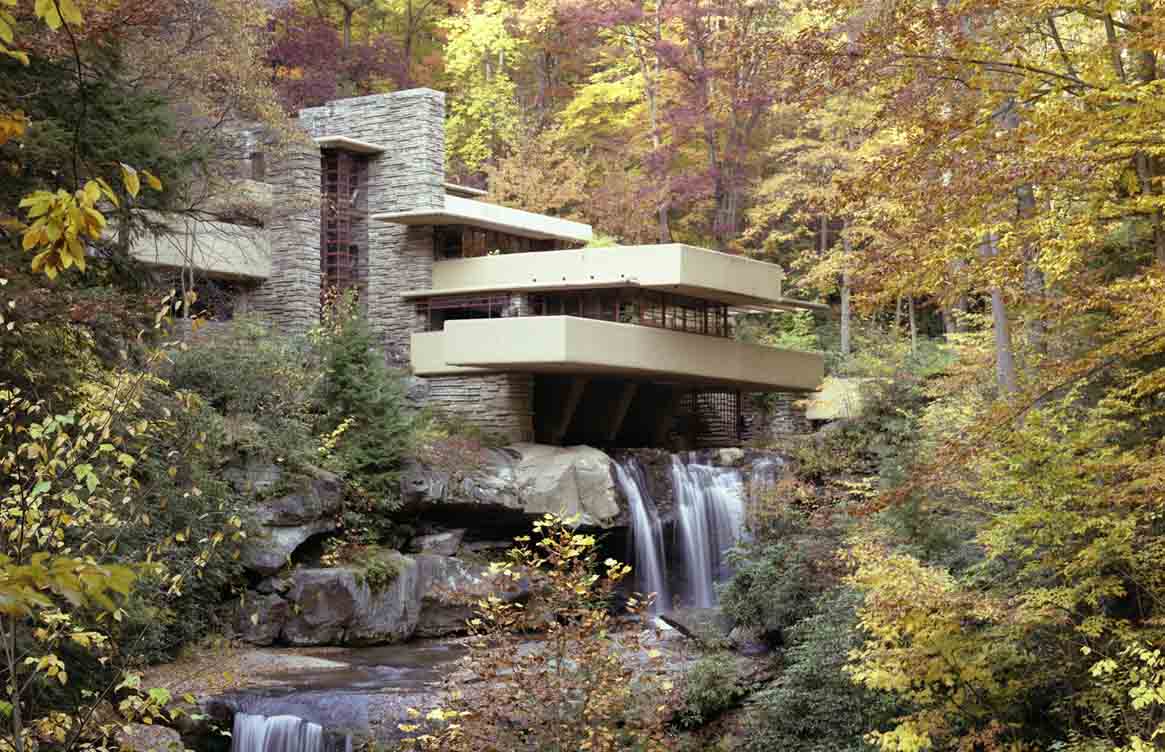

The Smithsonian Magazine in 2008 named Fallingwater in Western Pennsylvania as one of the “28 places to visit before you die” along with the Taj Mahal, Machu Picchu, the Pyramids at Giza and the Grand Canyon. This glorious house, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1935, appears on nearly every architect’s list of the best buildings of the 20th century. In July 2016 it was referred by the UNESCO committee to its World Heritage list for consideration. What has made this family home inspire such praise?

Fallingwater was designed (legendarily in a few hours) by Frank Lloyd Wright for the Kaufmann family, wealthy owners of a department store in Pittsburgh. The family summered in cabins in the Allegheny Mountains and wanted a permanent house overlooking a favourite waterfall on Bear Run, the creek running through their property. Frank Lloyd Wright chose to site the house not overlooking the falls, as they had suggested, but directly over them in a series of dramatic cantilevers extending from the boulders on the north side of the creek: “No, not simply to look at the waterfalls but to live with them” he insisted. Logically, such a radical design in concrete and steel should have violated its tranquil natural setting, but instead the building and its surroundings are better together than they could ever be apart. “Can you say,” Wright challenged his apprentices, “when your building is complete that the landscape is more beautiful than it was before?” He could certainly say so here.

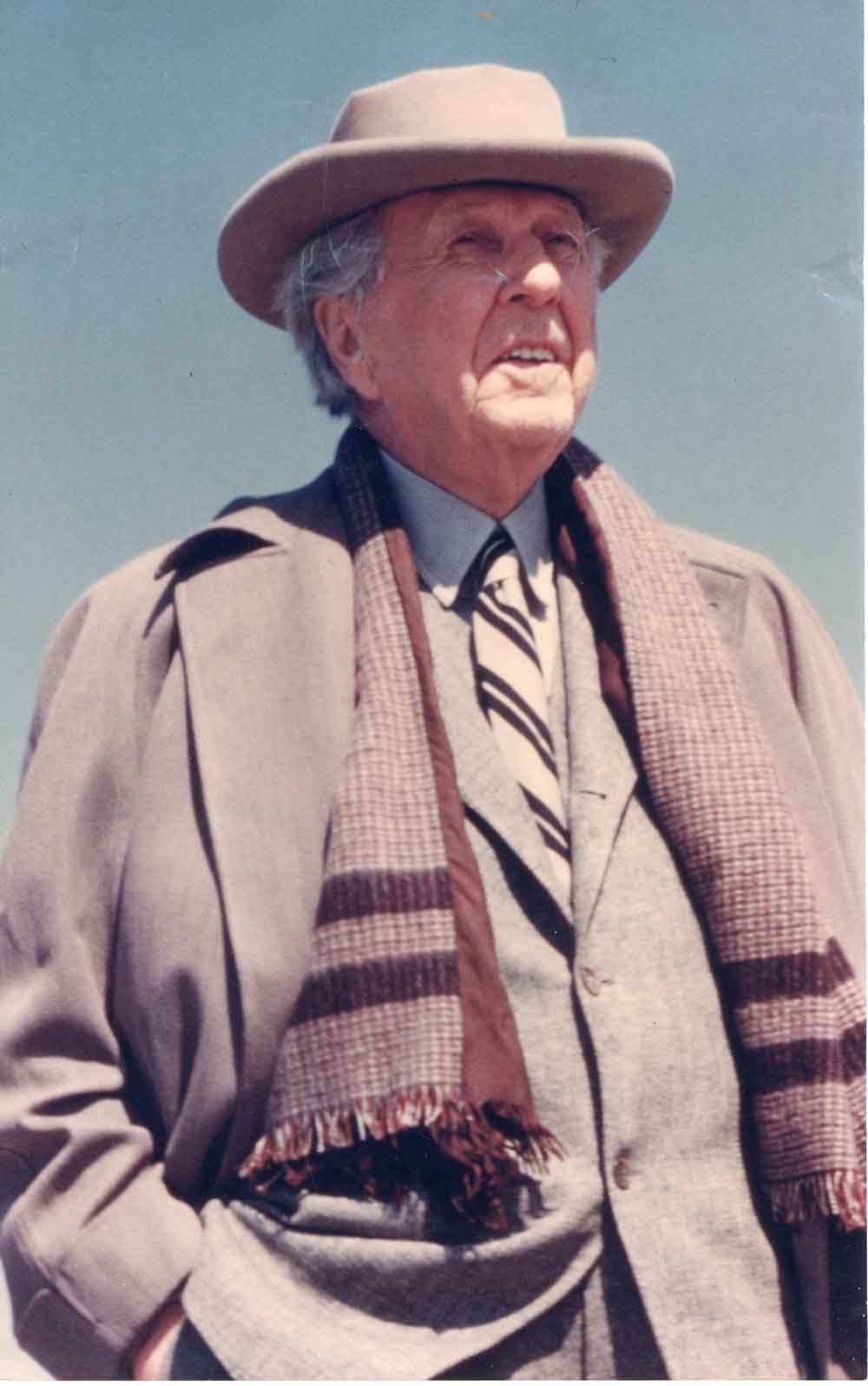

The house was designed late in Wright’s career, after a fallow period when he had been largely overlooked by the New Modernists. From the beginning he had developed a theory of architecture which he called ‘organic’. After his marriage in the 1930s to his third wife, Olgivanna Ivanovna Lazovich, a former student of Gurdjieff, he entered a new period of creativity and was encouraged by her to teach his philosophy in the Taliesen Fellowship they founded together.

“To take this matter of organic architecture a little deeper into the place where it belongs – the human heart – the design matter in this issue falls readily into the following sensuous expressions of principle at work. It is the sense of the whole that is lacking in ‘modern’ buildings I have seen, and we are here concerned with that sense of the whole which is radical.”

This was an architecture developed from within, not made to fit inside applied forms. Starting with nature, which included the principles governing the natural world of geometry and mathematics, an architecture could emerge which was not enslaved by historical form. He considered this to be profoundly democratic, and related organic architecture to the founding principles of America: he saw a building as a place where the individual, liberated from history and tradition, could free his spirit:

“Every man’s home is his ‘castle’! No, every man’s home is his sphere in space – his appropriate place to live in spaciousness… No less but more than ever this manly home a refuge for the expanding spirit of man the individual.”

Frank Lloyd Wright’s only formal training was as an engineer, and he never ceased to develop and experiment with new engineering ideas inspired by nature. He lived at a time – the late 19th and early 20th centuries – when radical new building materials were being developed: concrete, steel, plate glass, and he embraced them all. These allowed him to ‘break out of the box’ of traditional masonry structures: concrete and steel could work in tension as well as compression, and glass could open up to the light in dramatic new ways:

“Let the modern now work with light, light diffused, light reflected, light refracted – light for its own sake, shadows gratuitous. More and more light began to become the beautifier of the building – the blessing of the occupants.”

The cantilever, the structural form which allows Fallingwater to soar across the waterfall, liberated the house to “break out of the box”. Because the only vertical supports are on the bank of the stream, the corners of the box, floating over the falls, could be entirely opened up to glass.

The iconic photographs of this building from below are well known, but to have the opportunity to walk into and around it shows another house altogether. Architectural photography is seductive but in the end it can only illustrate forms and surfaces: a sense of depth and a sense of space is only realized by being physically present.

What is surprising is how comfortable the house is. Though there is nothing modest about the concept (nor the cost of construction: Wright exceeded the generous budget by a factor of five), the drama of the design in no way overwhelms the sense of ‘home’. It is not as big as it seems from outside: there are four small bedrooms and bathrooms, a small kitchen and one large living/dining room. Not for Frank Lloyd Wright the triple storey entrance foyers of modern day mega-mansions; all the space is given over to living, not to impressing. The entrance is small and dark and, in a few steps, draws you in to the surprise of the glorious living space, low-ceilinged but flooded with light, with the glass corner windows, which repeat throughout the house, overlooking the creek. Steps lead down, magically, from the room into the pool at the top of the falls, and a large cantilevered deck draws you out into the woods and over the water. Each of the rooms spread over the three storeys reiterate this: small staircases and passageways leading to gem-like spaces, flooded with light, drawing the visitor to the beauty outside.

Thus, despite its radical design and its exorbitant cost, Fallingwater is extremely liveable-in. It manages to be dramatic, inspiring, uplifting and yet still remain comfortable and comforting. It is a bold house – the inhabitant or visitor cannot passively overlook the woods and the water but is thrust into the centre of them and would have to be soulless not to feel engaged with the beauty of the place. The design and its setting is completely integrated. It reveals Wright’s principles of organic architecture far more profoundly than even his eloquent writings could:

“The conception of the room within, the interior spaces of the building to be conserved, expressed and made living as architecture – the architecture of within – that is precisely what we are driving at.”

The Smithsonian life-list is inevitably debatable, but it is interesting that Fallingwater is the only example of residential architecture, and the only design from the 20th century, to meet their standards. Wright might have appreciated that they did not choose a prestigious public building but a family home, as his radical reinterpretation of domestic architecture was one of the great achievements of his long career. It was also profoundly influential, being the foundation of the canon of great American 20th-century homes. However different the style and appearance of their work, the modernist houses of the Bauhaus architects who arrived in America in the 1930s also reinterpreted “from within” – as all good architecture must – acknowledging the truth of his saying:

“The circumference of architecture is changing with astonishing rapidity but its center remains unchanged – the human heart.”

It is unlikely that there is any architect working today who has not been influenced in some way by Frank Lloyd Wright, whether or not they are familiar with his philosophy. He was notoriously arrogant and – interestingly, as a great proponent of democratising design – extremely autocratic with his clients. He was also experimental to a fault: many of his buildings, including Fallingwater, have needed extensive structural refits. But none of this matters when you experience the building. Though some of his clients found him intolerable, the Kaufmanns’ appreciated his vision and loved Fallingwater. After many happy years there, their son donated it to the public so that we could all experience how this vision – this “radical sense of the whole” – found three-dimensional form:

“Beautiful buildings are more than scientific. They are true organisms, spiritually conceived.”

NEVER MISS AN ARTICLE

Please follow and like us:

CATEGORIES

Email this page to a friend

Email this page to a friend

Image Sources

Our thanks to the Western Pennsylvania Conservatory for all the images used in this article.

Other Sources

All quotes from Frank Lloyd Wright, In the Realm of Ideas, Southern Illinois University Press, Illinois,1988.

Jane Carroll studied at the Architectural Association in London and practices in Ojai, California. She is also the secretary of the U.S. branch of the Muhyiddin Ibn ‘Arabi Society. In 2014, Jane delivered the annual Beshara Lecture, titled: A Heart Capable of Every Form: Atheism, Agnosticism and Belief.

NEVER MISS AN ARTICLE

If you enjoyed reading this article, please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

Please follow and like us:

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE:

1