Metaphysics & Spirituality _|_ Issue 28, 2025

The Vision of Esalen

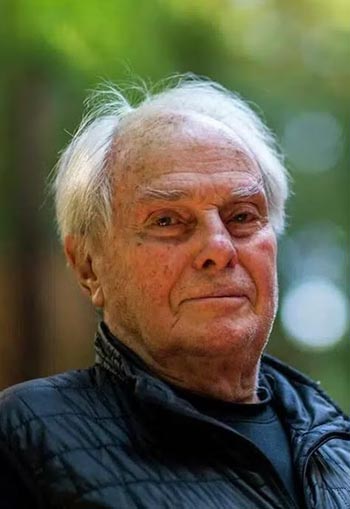

Michael Murphy, co-founder of the Esalen Institute in California, reflects on the contribution of an institution that has revolutionised our understanding of spirituality

The Vision of Esalen

Michael Murphy, co-founder of the Esalen Institute in California, reflects on the contribution of this seminal project, which has revolutionised our understanding of spirituality

The Esalen Institute [/] in Big Sur, California, has been enormously influential upon contemporary culture. Founded in 1962 with the aim of supporting alternative methods for exploring human consciousness, it pioneered the study of Eastern philosophies in the Western world and quickly became famous as the home of the ‘counterculture’ and the human potential movement. An extraordinary group of leading-edge thinkers and practitioners gathered under its umbrella and many of the ideas and practices they explored – from yoga to alternative medicine and transpersonal psychology – have since become mainstream. In this interview, its co-founder, Michael Murphy, now in his 90s, talks to Jane Clark and Nick Yiangou about the vision of Esalen, its future development, and the philosophy that he has personally embraced, ‘evolutionary panentheism’.

Jane: You established the Eselen Institute in 1962 with your colleague Dick Price. It was quite unlike anything that had been set up in the States before, and it turned out to be enormously influential and attracted some amazing people as teachers and researchers. Can we begin by asking you a bit about your history and what your intentions were in founding it.

Michael: Let me say, first of all, that the deep mantra of my life, really, is how best to serve this great cosmic unfolding that we’re all involved in together, whether we know it or not. In relation to Esalen, which has been going now for 62 years: well, when we first started it, we conceived of a whole plan for it and wrote out a distillation of the ideas we had in my mind – a list of principles that we could really swear to. For example, ‘no one captures the flag’, which was a metaphor for our resolution that we would not fall prey to cultish behaviour or structures. But we were really flying blind. I mean, we were brand new. We were 30 years old and had no business experience.

Jane: You established the Esalen Institute in 1962 with your colleague Dick Price. It was quite unlike anything that had been set up in the States before, and it turned out to be enormously influential, attracting some amazing people as teachers and researchers. Can we begin by asking you a bit about your history and what your intentions were in founding it.

Jane: You established the Esalen Institute in 1962 with your colleague Dick Price. It was quite unlike anything that had been set up in the States before, and it turned out to be enormously influential, attracting some amazing people as teachers and researchers. Can we begin by asking you a bit about your history and what your intentions were in founding it.

Michael: Let me say, first of all, that the deep mantra of my life, really, is how best to serve this great cosmic unfolding that we’re all involved in together, whether we know it or not. In relation to Esalen, which has been going now for 62 years: well, when we first started it, we conceived of a whole plan for it and wrote out a distillation of the ideas we had in my mind – a list of principles that we could really swear to. For example, ‘no one captures the flag’, which was a metaphor for our resolution that we would not fall prey to cultish behaviour or structures. But we were really flying blind. I mean, we were brand new. We were 30 years old and had no business experience.

I had been in India, where the idea of some kind of institute had been brewing in my mind. I knew that my family owned this gorgeous stretch of land in Big Sur – two miles of coastline which was really pretty priceless; my grandfather had wanted to build a spa there. So when I returned to the States I went to my grandmother, Bunny, to ask her about the property. At first she said no. She told our family that none of us should ever give anything to Michael because he will immediately give it to the Hindus. She spelled it ‘Hindoos’ because she’d been reading Kipling!

My family had been very shocked by let’s call it my ‘flip’. I had been enrolled on a pre-med course at Stanford University, and one day, by accident, I wandered into a class given by the great Professor Herbert Spiegelberg [/], who’d gotten out of Germany in 1937. He was a friend of the existential philosopher Paul Tillich [/]. I was 19 years old and here was the famous Spiegelberg! I said to myself, well, I’ve heard about this, so I’ll stay. He came in – and I’ll just take a minute to tell you this, because it had such a dramatic impact on me and 600 other semi-restless late adolescent Stanford students. He came in and with his courage and presence, he brought those 600 kids to attention – just with silent presence. Goodness.

And then he said one word: ‘Brahman’. Well, my life changed forever. It was the second lecture of his course on comparative religion, and he talked for 45 minutes on the subject of the Vedas and early Upanishads. He ended with another word, Atman, which is Brahman. I walked back to my fraternity with one sentence going through my head, ‘You’ll never be the same. You’ll never be the same.’

Anyway, one thing led to another, and I dropped out of my pre-med training. I quit my fraternity. I started living alone and fell in with a group of students who were studying or dwelling upon Sri Aurobindo’s Life Divine.[1] Eventually, I spent a year and a half at the Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry in India. It was there that the idea for Esalen started to grow in me. By that time, my grandfather had died, which is why I asked my grandmother about the land in Big Sur.

Michael Murphey and Dick Price at Esalen in 1985. ‘No-one captures the flag’. Photograph: Esalen Institute [/]

Nick: You were already working with Dick Price at this point?

Michael: Yes, I was 28 and had met Dick, who shared this embryonic set of feelings with me. He had been at Stanford at the same time as I had. He had been deeply wounded by having his own mystical turn in a very disadvantaged place, the Air Force. His family was quite prominent – his father was good friends with the Secretary of War – so they got him an honourable discharge on condition that he be ‘cured’ from the state he was in. This led him to be put in a mental institution for a while.

Dick and I went down to the Big Sur property for a retreat and discovered that the most amazing circus was underway there. Henry Miller, Anais Nin and Lawrence Durrell were coming down to the hot springs, and it was not only a bohemian crowd that was gathering there on the weekends; it was a gay crowd. It had an international flavour, with guys from Paris and all over. My grandmother had turned the property over to a charismatic church cult, and the people there were out of control.

Anyway, to cut a long story short, eventually my father persuaded her to let me take it over. But then it took us some time to get it under control. Those days in that place, no one believed in private property and there were Marxist outlaws inhabiting Big Sur. My family was prominent in Monterey County, so we had enough good standing, but when we tried to get the sheriff to help us, he refused. He was a southern guy and when I went up to talk to him, he asked: ‘You boys have guns?’ Uh, no, we don’t have guns. ‘You boys, you get yourself some guns because I’m not sending my men to your bad land.’ So it took us about a year to get those two miles of coast into a state where we could start. Then we found we had a set of virtues that wasn’t quite up to the challenge, so we had to revise our portfolio as we evolved.

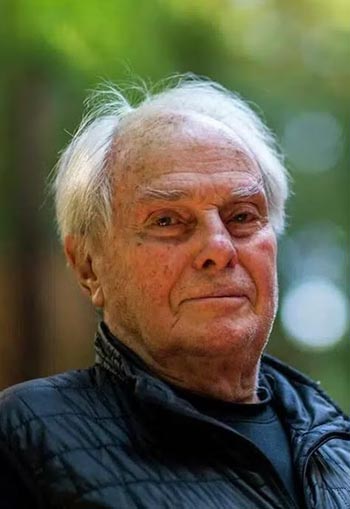

Abraham Harold Maslow, psychologist, famous for his ‘hierarchy of needs’ in which the highest is self-actualisation. ‘What is necessary to change a person is to change his awareness of himself.’ ‘Image: purposefairy.com

The Esalen Vision Takes Shape

.

Nick: So what was it that you were aiming to achieve?

Michael: The basic idea was to open up discussions and experiential explorations that we had both found impossible at Stanford or Harvard, or in mental hospitals. This would be an exploration into the greater life and human nature that’s pressing to be born in us. Sri Aurobindo framed this in the way he did, but there was a whole cast of other characters that we’d been reading, like Henri Bergson who had won a Nobel Prize, who I believed were forming – in a way which was not being described by sociologists or anthropologists – a new culture involving a new understanding of evolution. We were also interested in developing a set of practices which were fitting for us as 20th century Americans, so that we did not always have to fit into the procrustean beds of the various practices of East and West.

We were very much, both of us, lit up and I would say really inspired, by Eastern thought. In my case, it was the vision of Sri Aurobindo, and I embraced an evolutionary perspective. So it wasn’t Hinduism as such that I was interested in; I was more interested in the truth that Atman is Brahman.

Jane: You mean by this that the individual soul and the universal soul are one? And therefore, as you have put it, our individual transformation is linked to evolutionary unfolding of the whole world?

Michael: Yes. When you look at all the great relgions, you find that there are common core beliefs. So we talked about Plotinus, we talked about the Neoplatonists, who also held what I refer to as ‘panentheistic views’, meaning that the divine is both transcendent to and immanent within every particle in this confluence. And that we, this assemblage of amazing particles and various forces that constitute human flesh, secretly harbour beatitudes and higher lights; we have amazing potential. This was the basic kernel of the idea, which I have since termed ‘evolutionary panentheism’.

Magic started to happen at Esalen after we had gotten control of the property. We really got underway when Abraham Maslow [/] – the psychologist who developed the well-known ‘hierarchy of needs’ – drove in one night not knowing what it was. I took it as a sign from above and beyond that from somewhere a guardian angel or whatever had sent him. Then we started attracting other people and we had what you might describe as a vertical take-off.

To this day, a substantial portion of any group that’s down there is from other countries. We’ve had some exchanges with people from 208 different places over the years – Europe, Latin America and increasingly Asia. We had a deep running thing which is now tragically broken off with Russia. From the beginning Esalen was international and open access, and it became a great place of conversation. Then, after a couple of years, the activity was increasingly based on experiential programmes, which today are often called ‘somatics’, with people like Charlotte Selver [/], Ida Rolph [/] and Moshe Feldenkrais [/] from Israel, etc.

Charlotte Selver, pioneer of somatics who developed Sensory Awareness at Esalen, with fellow practitioners Don Hanlon Johnson [/] and Charles Brooks. ‘People who don’t love the moment are always trying to achieve something, but when one is on the way, every moment is “it”.’ Photograph: Joyce Lake/Esalen

Somatic Practice

.

Nick: Can you say more about your understanding of somatics? As I understand the term, it can refer to traditional practices like yoga or tai chi, but also modern techniques like the Feldenkrais method or the Alexander technique. Esalen also pioneered things like Gestalt Therapy and encounter groups.

Michael: Somatics are mind–body disciplines looking to release the greater life that’s trying to be born in us – a set of practices that naturally overflow the metaphysical constraints that every great religion has necessarily adopted and which have become a kind of glossy or golden cage through which our human nature is trying to expand. That’s why I often say that we’re all, whether we know it or not, together involved in a cosmic jailbreak from one point of view, breaking out of our golden chains. But on the other hand, we need to deeply appreciate the general shape of the jail.

In other words, the idea that Atman is Brahman is a bottom-line truth. We come to realise that this bottomless, eternal subjectivity is one with all as we learn, through whatever hundreds of practices there are, to detach ourselves from the rising contents of our mind. This is an ongoing process during which the new freedoms that start to blossom in us are connected, successively, with different levels of what you might call subtle matter.

Nick: Would you say this development of somatics is one of the key legacies of Esalen?

Michael: Yes, there were marvellous discoveries and progress on certain fronts. People were learning a lot about the human body and the different ways forward in the practices to relieve pain, to loosen up muscles, etc. But I think it is important to also recognise that in the early days we made mistakes. One of these was that we all fell in love with everyone else, and some of the younger folks wanted to go on to enact this by making love physically. This was an epistemological error writ large in the flesh. We had to outgrow that.

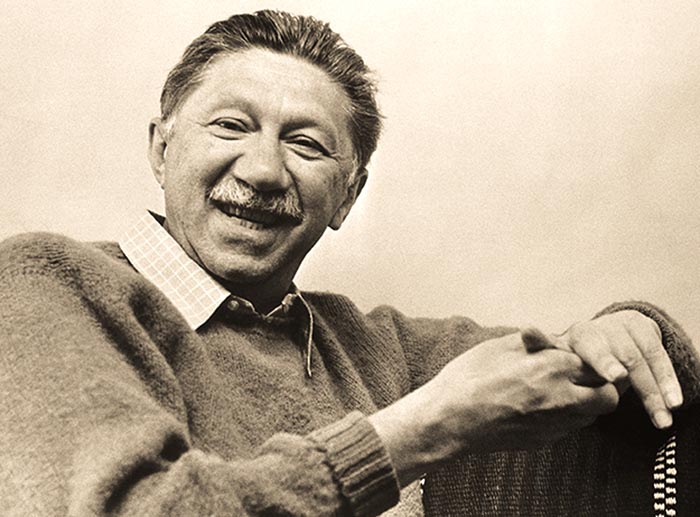

There were other practices, as well, that brought deliverance, but at the same time generated a lot of problems. These included the use of the psychedelics. We became a real centre for people like Timothy Leary [/] and Richard Alpert [/] – and Aldous Huxley [/], who was a big influence on us, even though he died in ‘63 after we’d been going just a couple of years. A kind of drunken mysticism broke out in the 1960s; there were certain slogans that went viral, such as ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’ and we became known for what was called the ‘counterculture’.

These first disclosures were us in kindergarten on the right path. I believe that whatever contribution we’ve made has come through both our successes and our failures – as long as we acknowledge them as failures. From the earliest years, I was saying that we have to confess our sins in public. I mean, we’re a learning community. We’re explorers. But it’s no good if you don’t tell people about mistakes. You’ve got to share them with the culture. So, it’s always a dialectic between the core aspects of this exploration and the necessities for what we would call esotericism to keep it going by moving off to the perimeter of the culture, which it was easy for us to do there in Big Sur.

Esalen is very much into this somatic work right now. This is where I think we’re going to make some interesting discoveries. Part of the Institute going underground for a few years and coming forward anew is a sobering up and a maturity. The whole enterprise is still in an early innings. Let’s call what’s happening now Esalen 2.0 or something.

Aldous Huxley, author and philosophy, who was a seminal influence at the very beginning of Esalen: ‘There is only one corner of the universe you can be certain of improving, and that’s your own self.’ Photograph: Keystone Press [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

The Center for Theory and Research

.

Nick: One of the directions that you went on to develop was somatics in athletics, exploring the correlation between the state of athletes at peak performance and people who have achieved states of Zen awareness. In 1971 you published a novel Golf in the Kingdom,[2] about a young man who comes across a mystical golfing expert while in Scotland. It’s been enormously successful, selling more than a million copies and being translated into 19 languages. You describe how, during a round of golf, at the 13th hole, the protagonist has a remarkable experience of a sort of mystical unity where his entire being – body, soul and spirit – flows into one action as he hits the ball. The way you describe it reads like a revelatory experience.

Michael: It’s 52 years now since I published that book and it’s the luckiest shot I ever hit because it’s still selling! I can honestly say that I probably know more about mystical experiences on golf courses than anyone else in the world, because I’m talking about it all the time. If I go to a country club and they hear I’m there, then it’s like Father Murphy taking confession; everyone wants to tell me the story of the latest experience they have had.

Jane: So, going on from this, in 1998 the Institute set up the Esalen Center for Theory and Research (CTR) [/], to try to put some science behind these somatic practices. Would you say that this is part of the process that you call ‘sobering up’ and becoming mature?

Michael: That’s right, though actually, from our birth, we always honoured the marriage of science and the religious, contemplative and shamanic traditions. But for the sake of campus politics, along the way, we decided we needed to ring-fence a set of programmes that were by invitation only, not open to the general public. They were, if not in the spirit of science, certainly in the spirit of disciplined inquiry and developing multi-dimensional research. Their structure was based on conferences which took place largely at Esalen but sometimes in other places, including Russia, sponsored by Esalen, bringing people together in the most unlikely sorts of combinations.

Now we are evolving the Center further to have more flexibility in its structures. And part of our idea is that our structure has to evolve to meet the challenge of empirical and intellectual disclosures. This is because our cages can be academic or religious or commercial or whatever. We humans form organisations to do this or that, but then we can get trapped by them.

Jeff Kripal, who is currently the J. Newton Rayzor Chair in Philosophy and Religious Thought at Rice University in Houston, Texas, is very central to what we are doing right now. He wrote a book recently called The Super Humanities.[3] This is basically a kind of Voltaire-ian indictment of the higher education system we now have in this country and of the genius it has developed in dismissing what doesn’t fit its preconceptions. Some people have learned to sneer with genius. One lifted eyebrow, one curl of the lip, and with this a professor can knock out a graduate student he’s working with.

I went through that a little because I did have a short period during my 20s where I went back to Stanford in graduate school to study philosophy. This was at a time when the analytic philosophers were taking over. Knowing that I was so lit up with meditation, they would, in a compassionate way, say to me: ‘Well, you know, Mike, when some of these mystics say they see God, it’s really just their way of saying they feel good’. This art of reduction is in our universities all the way through.

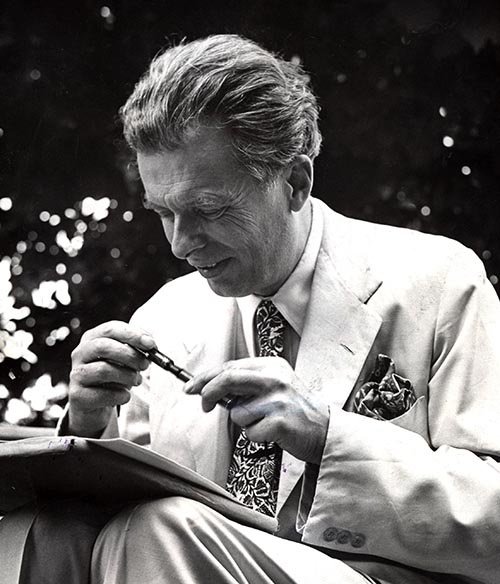

Carl Rogers, one of the founders of humanistic psychology [/], known especially for his person-centred approach. ‘The good life is a process, not a state of being. It is a direction not a destination.’ Photograph: https://gohighbrow.com/carl-rogers/

Evolution and the Emergent Creation

.

Nick: Coming back to something you mentioned earlier about your passion for the evolutionary impulse to move in a new direction. I know that you have embraced a way of looking at this which you call ‘evolutionary panentheism’ [/], in which both the body and the spirit are aspects of an emergent creation. What’s your sense of what is emerging?

Michael: Well, that’s the 64 million dollar question. In my book, The Future of the Body,[4] at the beginning, to frame it, I said that evolution meanders as much as it advances. And among mainstream people who call themselves evolutionary theorists, ‘evolution’ is kind of a loose term. I don’t think there is a field of evolutionary theory as such. I mean, evolution is a feature of physics, it’s a feature of the cosmos, of biology and of culture. But to talk about evolution, we need criteria if we’re going to think of it as progressive; we have to define what we mean by progress or advance. This has been a big ongoing theoretical, you could even say metaphysical, aspect of our discussions at Esalen. What are the grand metaphors to describe it?

So, here’s my take on this. Certain people will tend towards engineering metaphors and will look for structure; it’s all structuralism, post-structuralism, etc. And you can see the engineer in these thinkers, even when they are colourful characters like Tim Leary, who would always come back to this kind of thing. I’m using this description for intellectual temperaments who tend to see things as predetermined.

Then there are those of a more artistic temperament who see it as a lila, in the Hindu sense – the divine play at the core of everything. So, it’s a jazz band – a cosmic jazz band, and we’re improvising, all of us. And then there are others like Rudolf Steiner who see it all as a series of avatars; even Sri Aurobindo would play with this idea of ascending avatars – Hanuman to Rama to Krishna, etc. Now, I think there are elements of truth in all these different framings. There are different metaphors. But I myself say: always go back to empirical disclosure. I’m on the side of the best scientists.

Jeffrey Kripal, J. Newton Rayzor Chair in Philosophy and Religious Thought at Rice University in Houston, whose work is central to Esalen’s new direction. ‘I love science! But let’s let science be science, and let’s not pretend it’s the only way to know the world.’ Photograph: Michael Spadafina

Ancient Truths in New Forms

.

Jane: So how do you see the future of the Esalen Institute?

Michael: I would say that we’ve had ups and downs, but we’ve persevered. We are cheerful and we’re excited, and we’re in the best economic shape we’ve ever been in. Of course, that’s not saying much, because at the beginning we were so incompetent. I was lucky that the inspiration to start something like this coincided with my having access to land, as that has been a big part of the success of Esalen. We’ve shown how much you can do even with that level of incompetence. In a way it’s an argument for the world being deeply good that we got this kind of break despite it. I wouldn’t push that argument too far, but the way I am seeing it, it indicates that the world is filled with opportunity.

We’re more experienced and we are battle-hardened. And the same goes for intellectual debates. We’ve gotten to a point where I do not want Esalen spending any more time reiterating old arguments, even with a lot of smart people. For example, we don’t really have to re-examine what we mean by telepathy. The term was coined 1882 by Frederic Myers at Cambridge in England, you know, in the Society for Psychical Research and it has been researched by many hundreds of projects. In my own book, The Future of the Body, I had 3000 citations which I collected over ten years.

So bye-bye to yesterday. After all, that’s the way science works. We’re not re-investigating the truthfulness of Einstein’s special theory of relativity. That was done 100 years ago. We have to examine things that are real problems, but we don’t have to keep going back over and over again to the same things.

So if somebody says: ‘When a mystic reports that they’re seeing the divine, they’re just saying that they feel good’, I’m saying: ‘Just go and read Plato’. I mean, he already was beyond that one two thousand years ago. Knowing the difference between dianoia and gnosis? You’re going to want to know the history of metaphysics. Or Indian philosophy, where vijnana is not exactly a higher disclosure, and there you even have deep knowledge of states, like the difference between nirvikalpa samadhi and savikalpa samadhi. I mean, this has been worked through again and again.

But we don’t have enough connoisseurs of history and of experience. There isn’t enough connoisseurship out there, so what we need to do is to bring and listen. Of course we still have some blind spots, but let’s move on.

Nick: Are you talking about a new narrative, a new way of looking at things?

Michael: I would say in some respects it’s actually an ancient narrative, but it’s being constantly refined and developed. There were seeds of evolutionary panentheism that you can find back in the time of the fifth century BCE. Within high Vedanta and the highest forms of Neoplatonism, there are deeply realised and often beautifully described insights and descriptions. But people then did not have modern science, and they didn’t have the insights of Charles Darwin. So they hadn’t gone through that developmental phase that we’ve had to go through. Even today, here in America, there is the Christian right that refuses to believe in evolution, and at Esalen we’ve had professors who are gloriously lovely human beings and tremendous appreciators of the perennial philosophy, but who stalwartly say evolution is not proven.

We need to properly embrace our emerging world with all our crap detectors going at the same time, having learnt how even the most exalted academics and Oxford and Cambridge dons can be wrong about certain things. We need to find the right balance between what has stood up through these 62 years on the practice side, as well as the insight and research side, and what is pressing to be born in us anew.

Nick: I think it’s a wonderful vision, Michael, and we’re so impressed that at 94, you’re still at the leading edge of thought and raring to go forward. Thank you so much for talking to us.

To read more about Michael’s model of evolutionary panentheism, click here [/].

To find out more about the Esalen Institute, see their website www.esalen.org/. They have a section devoted to the history of the Institute and the extraordinary cohort of people who taught there, click here [/].

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: The Esalen Institute at Big Sur.

Inset: Michael Murphy [/].

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] SRI AUROBINDO, The Life Divine ( Lotus Press, 1949).

[2] MICHAEL MURPHY, Golf in the Kingdom (Penguin, 1971).

[3] JEFF KRIPAL, The Super Humanities: Historical Precedents, Moral Objections, New Realities (Chicago University Press, 2022).

[4] MICHAEL MURPHY, The Future of the Body: Explorations into the Further Evolution of Human Nature (J.P. Tarcher, 1992).

The text of this article has a Creative Commons Licence BY-NC-ND 4.0 [/]. We are not able to give permission for reproduction of the illustrations; details of their sources are given in the captions.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Ayurveda: A Medical Science Based on Consciousness

Elizabeth Roberts talks to Dr Sunil Joshi, and explains how India’s ancient system of healing recognises the unity of the body and the mind

Yoga: A Spiritual Practice for Our Time

An interview with the distinguished American teacher Judith Hanson Lasater, developer of Restorative Yoga

Mindfulness Meditation – Alleviation of Suffering for Neurological Conditions

Niels Detert, neuropsychologist at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, explains how meditation can help people with long-term medical problems

Mind and Matter Entangled

Dr Dean Radin of the Institute of Noetic Sciences in California talks about a lifetime of experimental work on the intersection of physics and consciousness

READERS’ COMMENTS

Great article! Looking forward to more of your posts.