News & Views

Book Review: Conversations with Dostoevsky by George Pattison

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance to our contemporary world

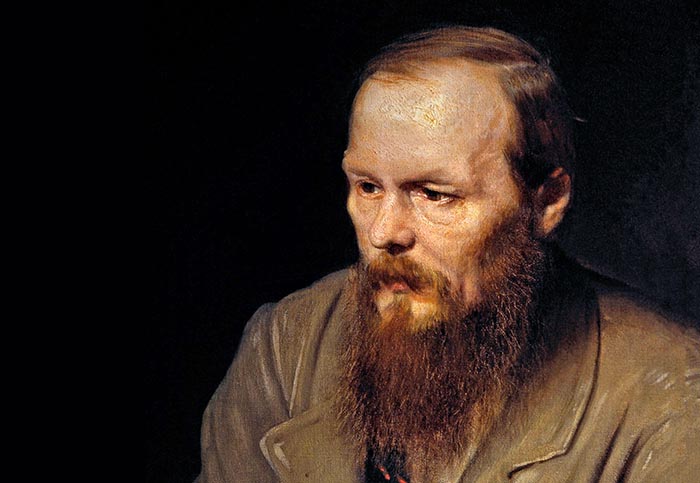

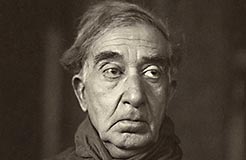

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky by Vasily Perov (1872). Image: IanDagnall Computing / Alamy Stock Photo

The work of the great Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881) remains enduringly relevant, particularly perhaps in times of psychic and social upheaval, such as our own. Nearly 150 years after his death in Imperial Russia, his unflinching portrayals of human suffering, delusion, cruelty and despair feel strikingly modern. This Christmas his short story of lovelorn urban loneliness, White Nights,[1] was an unexpected bestseller in the UK. Yet Dostoevsky’s profoundly religious response to the tragedy of human existence is less contemporary. For us, the heirs of Freud, such pathologies as Dostoevsky portrays with intimate understanding are now seen as the concern of the psychiatrist rather than the priest. They are anomalies from which we seek to be released rather than inevitable manifestations of our fallen nature from which we need to be redeemed.

It is precisely Dostoevsky’s ability to confront the darkest aspects of life and the human soul while offering a transcendent vision of repentance, redemption and love, that makes his work one of the most compelling literary arguments for a Christian perspective on human existence. It is an argument which he does not make through essays or sermons, but weaves into the fabric of his novels through vivid dialogue and dramatic storytelling.

While countless books and academic studies have dissected Dostoevsky’s works, none have done so in the way that Professor George Pattison does in Conversations with Dostoevsky. What makes this study unique is its unconventional approach: fiction as a means of examining fiction. The book’s second half is a more traditional academic analysis of Dostoevsky’s work and ideas, but the first half takes the form of a bold imaginative exercise in which Dostoevsky himself appears to the narrator in the latter’s Glasgow apartment between November 2018 and spring 2019 for a series of fictional conversations. Inevitably there is an echo here of the Devil’s appearance to the sceptic Ivan Karamazov in Dostoevsky’s novel, where he seems to be a manifestation of Ivan’s buried conscience.

Does the novelist’s arrival in modern Glasgow have the same origin? His appearances are always unannounced and take place not only in the narrator’s apartment but also in locations across Glasgow, including the Botanic Gardens and the city’s famed Necropolis. Each is a prelude to a debate about Dostoevsky’s work and ideas, which often ends inconclusively, with the narrator left vaguely dissatisfied and no consensus achieved. Though the narrator is, like Pattison himself, also an academic at Glasgow University, he is clearly not Pattison in disguise. Unlike him – an Anglican priest and former Professor of Divinity at Oxford and Glasgow – the narrator is a disillusioned, secular figure burdened with questions rather than convictions, who teaches literature rather than theology.

Similarly, the Dostoevsky who steps into this contemporary setting is not merely a ghostly replica of the Russian novelist. He is aware of the values and concerns of the 21st century world he has entered (he even refers at one point to a ‘lifestyle choice’) and has an understanding of the impact his work has had in the years since his death. He also speaks fluent English – though, intriguingly, he suggests at one point that this is merely how the narrator hears his words, rather than proof of actual linguistic ability.

The Day Before the Exam (1895) by Leonid Ossipovitch Pasternak. Book cover of the Penguin Classics edition of The Brothers Karamazov

A Dramatic Form

.

The question that naturally presents itself to the reader of Conversations with Dostoevsky is: why has the author decided on this curious stratagem in his attempt to come to grips with the Russian novelist and his ideas? It certainly demands a radical suspension of disbelief; however serious the subsequent discussions, there remains something vaguely comic in the idea of the notoriously passionate and intense Dostoevsky suddenly turning up in the 21st century to debate with a British university lecturer whose attitudes and prejudices reflect those of the present liberal intellectual consensus. We could ask what they could possibly have to say to each other. But perhaps that is also the point: what exactly does Dostoevsky have to say to people of the present age, and what should we learn from him?

Despite the surreal nature of Dostoevsky’s arrival in his home, the narrator is convinced enough of his visitor’s authenticity to engage in sustained debate with him, though he tells no one of these extraordinary encounters, not even his wife (though at times she seems to suspect something is afoot). The ensuing conversations examine the novelist’s advocacy of faith in God, Christ, and immortality, and touch on a wide range of topics: suicide, truth and lies, guilt, determinism, literature, the Bible, film adaptations of Dostoevsky’s work, ‘the woman question’, nationalism, the Church, ‘the Jewish question’, and the nature of God, among others. At one point they are joined in Glasgow’s Kelvingrove Park by the Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyev, another contemporary of Dostoevsky, and together they discuss nationalism and the brotherhood of man.

These dramatised discussions reflect Dostoevsky’s own method in his novels, where meaning is teased out through the interactions (and often violent conflicts) between literary creations who express and represent vastly different visions and points of view (as with the three Karamazov brothers), often leaving the novelist’s own views unclear or only implicit. The power of the technique is that it demands that the readers themselves enter into the debate imaginatively and emotionally – it is not simply a matter for intellectual study. Dostoevsky asserted more than once that understanding is achieved primarily through the heart, rather than the rational mind, and the dry and dispassionate intellectualism (in his view) of the West was a particular object of his contempt, seeing it as a dilution of our humanity. This is shown here in his scornful judgement of the German philosopher Hegel, whom he read while he was exiled in a prison camp in the east of Russia. Hegel, he maintains, had nothing to say about the endless sorrow of his fellow man, and even declared that ‘Siberia is excluded from world history’ as though all that humanity and suffering was irrelevant.

The narrator is particularly troubled by aspects of Dostoevsky’s legacy that challenge modern liberal sensibilities: his staunch Russian nationalism, his defence of Tsarist imperial rule, signs of male chauvinism and antisemitism, and especially the ways in which his ideas may have influenced the rise of fascist and racist ideologies in the 20th century. These are difficult questions, to which the conversations provide no definitive conclusions; instead, the book uses fictional dialogue to explore multiple perspectives, allowing these controversies to be examined in a nuanced and dynamic way. This approach is seen particularly in the description of a dinner party, where a group of Glasgow intellectuals debate Dostoevsky’s views on women, religion and society and no consensus of opinion is achieved.

The Glasgow Necropolis, one of the sites where Conversations with Dostoevsky is set. Image: robertharding / Alamy Stock Photo

Guilty!

.

The breadth and depth of the subjects discussed in this book cannot be fully covered in a short review. However, for me, the most profound and challenging question emerges in the very first conversation, in the chapter titled Guilty! Dostoevsky appears to the narrator as the latter is reading A Gentle Creature (also translated as The Meek One), a short story Dostoevsky published in 1876. If you have not read it already, I cannot recommend it too highly. It is another psychological monologue (like White Nights), devastating in its truth-telling, narrated by a pawnbroker who recounts his tumultuous relationship with his young wife shortly after she has taken her own life. She was a poor but courageous girl whom he had treated with extreme coldness, withholding love and affection to maintain control and bolster his own self-image. His lack of kindness or compassion ultimately drives her to unbearable despair, and she jumps from an upstairs window while he sleeps, clutching an icon of the Virgin Mary – the image of selfless love – as she falls to her death. The power of the story is in the fact that the pawnbroker remains oblivious of his own deep culpability for his wife’s death. Even as he reflects on the events leading to her suicide, he is filled above all with self-pity, feeling abandoned and alone, deprived of the one person who might have loved him but blind to his own criminal failure to love.

This refusal to acknowledge guilt contrasts sharply with the words of Markel, the young brother of the elder Zosima in The Brothers Karamazov, who, on his deathbed, declares: ‘Each of us is guilty in everything, before everyone, and I most of all.’ When his mother protests that he is too young and innocent for such self-reproach, he insists: ‘Dear Mother, […] you must know that in truth each of us is guilty before everyone, for everyone and everything. I do not know how to explain it to you, but I feel it so strongly that it pains me.’

Markel’s radical view – that guilt is not merely the consequence of our actions but intrinsic to our nature – deeply unsettles the narrator. In modern thought, guilt is often framed as a psychological burden that hinders personal freedom, something to be relieved through therapy or denial. Dostoevsky argues that because we do not recognise that life and the world are gifts for which we should be forever grateful, and because we never love as fully as we should, we are all culpable. True self-knowledge begins with recognising this fact. Against the modern focus on self-realisation and personal fulfilment, Dostoevsky asserts that our primary duty is to others, making our guilt inescapable. But acknowledging this truth need not paralyse us. On the contrary, it invites transformation – an abandonment of the illusion of self-sufficiency that keeps us from acknowledging who we really are.

As with all the conversations that follow, this one does not reach a neat or unambiguous conclusion. The narrator remains troubled, finding the emphasis on guilt unnecessarily harsh. Yet Dostoevsky’s claim hangs over all the discussions that follow, just as Markel’s words echo throughout the pages of The Brothers Karamazov.

In Conclusion

.

Conversations with Dostoevsky is a distinctive contribution to the continuing appreciation of the Russian writer, and one that is especially relevant at a time when our optimism and even complacency about inevitable progress is being challenged in ways we did not anticipate. Our societies are fracturing and the harm we are doing to the planet and to our souls becomes ever more apparent. Part of the present challenge, of course, has come from Russia itself, and Pattison includes a reference to the recent invasion of Ukraine at the end of his book, wondering how Dostoevsky would have viewed it. This book makes clear how much this Russian novelist from the 19th century still has to say to us. However, we are left with an inevitable question: is it something we are prepared to hear?

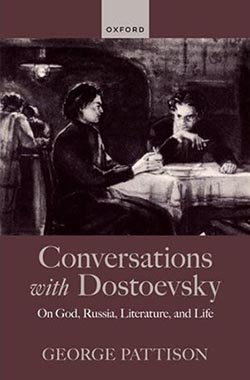

Conversations with Dostoevsky; On God, Russia, Literature and Life was published by Oxford University Press in 2024.

Conversations with Dostoevsky; On God, Russia, Literature and Life was published by Oxford University Press in 2024.

Sources (click to open)

[1] FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY, White Nights (Penguin Classics, 2016).

Andrew Watson is a writer and translator presently living in the UK.

The text of this article has a Creative Commons Licence BY-NC-ND 4.0 [/]. We are not able to give permission for reproduction of the illustrations; details of their sources are given in the captions.

read more in beshara magazine

More News & Views

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

Book Review: ‘Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature’

Richard Gault reviews a new book by Federico Faggin, one of the leading lights of the science of consciousness

An Irish Atlantic Rainforest

Peter Mabey reviews a new book by Eoghan Daltun which presents an inspiring example of individual action in the face of climate change

In Memory of Bill Viola (1951–2024)

Jane Carroll pays tribute to the acclaimed video artist, who died on July 12th 2024

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

READERS’ COMMENTS

0 Comments