News & Views

Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature by Federico Faggin

Richard Gault reviews a new book by one of the leading lights of the emerging science of consciousness

Federico Faggin lecturing to students at the University of Calabria in Southern Italy in 2023. Image: www.unical.it

This book is a tour de force: a magisterial, very possibly seminal work, by the extraordinary Italian scientist Federico Faggin. It is somewhat ironic that Faggin studied at the same university – Padua in Northern Italy – as Galileo. Galileo helped pave the way for the scientific revolution of the 16th century. Now Faggin comes to transcend that science which was so impressively developed by people like Descartes, Newton and Einstein, pointing to a richer vision of reality and a truer way for it to be known.

The conventional point of view that most people today implicitly believe is that material stuff is built up from atoms. This belief has been undermined by the revelation of quantum physics that beneath atoms lies immaterial information. But Faggin has gone a step further, proposing that the meaningless information of quantum physics hides the meaningful reality of consciousness. Look around you, he implicitly invites, and understand that everything you see is actually consciousness revealing itself in a different guise.

The genesis of the book lies in Faggin’s extraordinary spiritual experience of over 30 years ago. As readers of his previous book Silicon [1] will know, he made his name as the inventor of the Intel 4004 microprocessor and its successors – the silicon chip which has been at the heart of the technological revolution that has transformed our world over the last fifty years. But, as he explains in the introduction to Irreducible, the fame and fortune that followed did not make him happy, until, as he approached his 50th birthday, he had a sudden revelation in the middle of the night:

I suddenly felt a powerful rush of energy emerge from my chest like nothing I had ever experienced before and could not even imagine possible. This alive energy was love, yet a love so intense and so incredibly fulfilling that it surpassed any other notion I had previously had about love. Even more surprising was the fact that the source of this love was me. […] I knew then without a shadow of a doubt that this was the substance out of which everything that exists is made. This is what created the universe out of itself. (p. 10)

He realised immediately that conventional science was completely unable to explain what had happened to him. Rather it was more likely to deny it. He subsequently dedicated himself to developing an explanation for his unique experience which itself would also account for more mundane, everyday events that science can deal with. After many years of work, his central conclusion is that ‘consciousness must be an irreducible property of the “elementary particles” of which everything is made. […] Everything in the universe must be conscious’ (p. 137).

Many other contemporary thinkers have reached the same conclusion; people such as Bernardo Kastrup, Iain McGilchrist and Philip Goff, whose ideas we have explored in the Beshara Magazine. So, what marks this book out? Basically, that Faggin is a physicist, and in this book he presents a new, comprehensive theory about the nature of physical reality which emerges from, and is consistent with the latest scientific discoveries. In particular, he has studied quantum phenomena and in this book he reveals the significance of the findings of quantum physics in a radically new way. The Nobel prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman once said: ‘Nobody understands quantum physics’ (p. 208). But it is possible that Faggin does. Indeed, a key feature of the theory he advances is that it resolves the odd features of quantum behaviour which contemporary, conventional physicists cannot explain. Moreover, although he can get quite technical at times, he presents his explanations in impressively eloquent and understandable terms.

Galileo’s podium in the Palzzo Bo, Univeristy of Padua, where he used to lecture. Image: Kumar Striskandan/Alamy Stock Photo

Out with the Old

.

In introducing a radically new way of understanding reality, Faggin first sets about sweeping away the old, conventional worldview, that of materialism and scientism. This worldview is familiar to all of us: we were taught it at school and college, and we absorb it unconsciously through the media we read or view. The story goes like this: the world is made out of material stuff and the way to know this stuff is through the methods of science, in particular by breaking it down into smaller pieces and studying these as if each is a thing in itself.

Modern technology is a testimony to the success of this worldview. It works, though the current ecological and environmental crises do raise questions about its ultimate efficacy, a concern that Faggin shares (pp. 122–3). But there are other valid reasons to question this worldview. There are important features of reality that science ignores or cannot account for. One is consciousness. The physicalist view is that this ‘emerges’ from matter, but there is no scientific explanation for how this happens. Yet scientists continue to hold to the belief that consciousness is a product of material forces, electrical impulses firing between the neurons of our brain.

Faggin points out that this belief has a corollary, which understandably scientists tend not to advertise, which is that it denies us the possibility of free will. The conventional worldview holds that our behaviour and all our thoughts and feelings are the product of matter and energy circulating through our bodies and brains. Our brain processes the stimuli it receives in a way its physical structure determines. Though we feel as if we can choose what to do, this is an illusion – as indeed is the sense that we have a self. We are sophisticated robots, not agents of our own destiny, spectators only of a show produced 13.8 billion years ago.

This view is diametrically opposed to how we think about ourselves and also to how artists, politicians, entrepreneurs and even scientists themselves believe they practise their professions. We feel that we can and do make choices, that we can be creative. Are we really all so wrong or is science itself badly mistaken? Faggin argues for the latter in this book, not simply on the basis of how we experience ourselves but also on the evidence quantum physics provides.

There is something that scientists do advertise – indeed it is their very raison d’être. That is that science seeks explanations for the behaviour of the physical universe in the form of universal principles which they call ‘laws’. There is no doubt that the laws which it has uncovered offer powerful predictive ability. Think of Newton’s Laws of Motion, the Laws of Thermodynamics, or Einstein’s Relativity Theory. These laws appear to rule over natural material and energy, but where did they come from? If reality is essentially physical, for consistency they would have to have arisen from the physical stuff of the universe. But surely the laws would have to have come before the physical stuff in order to be present to guide its behaviour when it subsequently appeared? Here is a riddle that science cannot solve. This is a crucial inability which is a major failing at the very heart of the scientific enterprise which Faggin’s theory seeks to address.

And finally, the enigma of life, which is a puzzle for science. In his A Short History of Nearly Everything Bill Bryson noted, with some surprise, that scientists cannot agree on a definition of what life is.[2] So it is not a surprise that they are unable to explain it. Consider a simple, single-cell bacteria, which is made up of 1010 atoms. How do these self-organise and operate seamlessly? Science has no answer and certainly no knowledge of how to arrange atoms to form a living entity. The only source of a living thing that is known is another living thing: life comes from life reproducing itself. So how did the very first living thing arise out of dead matter 3.5 billion years ago? Science can offer little else than to class this as a miracle, the first of many. Faggin quotes Isaac Bashevis Singer: ‘Materialist thinkers have attributed more miracles, improbable coincidences, and wonders to the blind mechanism of evolution than any theologians in the world have ever been able to attribute to God’ (p. 163).

Representation of the gravitational field in which the earth sits. Image: www.youtube.com

In with the New: Fields and Information

.

After identifying these shortcomings in the first few chapters of the book, Faggin proceeds to set out his new vision. This is based on something he and physicists do agree on – namely that information, specifically quantum information, is the core of everything. Information, not atoms, not electrons, not anything material, is the basic ‘stuff’ of the physical world.

What is the source of this information? Again, Faggin and the classical (as he calls them) scientists are in agreement: quantum information emerges from a unified field. The concept of a field may be harder for the layman to grasp than that of information, and yet we are all ever more familiar with fields that yield information. We have never seen and never will see a field, but the words you are now reading have reached your computer screen via such a field. Their reality is not in doubt. The difference between the classical physicists and Faggin is that the former are still hunting for the universal unified field which they feel is needed to bring quantum phenomena (particularly quantum gravity) and macroscopic phenomena (particularly the ‘ordinary’ gravity that Einstein explained in his theory of General Relativity) into a single theory, whereas Faggin claims he has identified it. He labels it ‘One’ (p. 175). From One all the phenomena of reality arise, he believes.

The most profound lessons Faggin wants us to learn are all to do with One because it is One that is the ontological reality. In the glossary at the end of the book he defines it as follows:

One: The totality of all that exists, both in potentiality and in actuality. One is irreducible, dynamic and creative. One is the interiority which connects all Its creations ‘from within’. (p. 305)

As a field, One cannot be directly known but what emerges from it can, namely information. By analysing information, Faggin uncovers what he believes the nature of One must be.

So, what is information? Quantum Information appears as readings on the sophisticated instruments physicists use to study quantum behaviour (such as CERN’s hadron collider). These provide data that the scientists employ to yield and test complex mathematical descriptions of what has been observed. For those who adopt a physicalist model, these mathematical models are essentially true descriptions of reality, some of them even going further and suggesting that they are reality – that reality is mathematics. But Faggin argues that they are making a fundamental epistemological error, confusing the map with the territory. And further: that the territory their models describe is not in fact the deepest physical level of the world we see around us, he argues, but rather the most primitive form of the world we experience inside us. He states: ‘I am convinced that […] quantum physics does not describe outer but inner reality’ (p. 182). This is an astonishing assertion: quantum physics models psychic rather than physical phenomena! How can he justify such a radical claim?

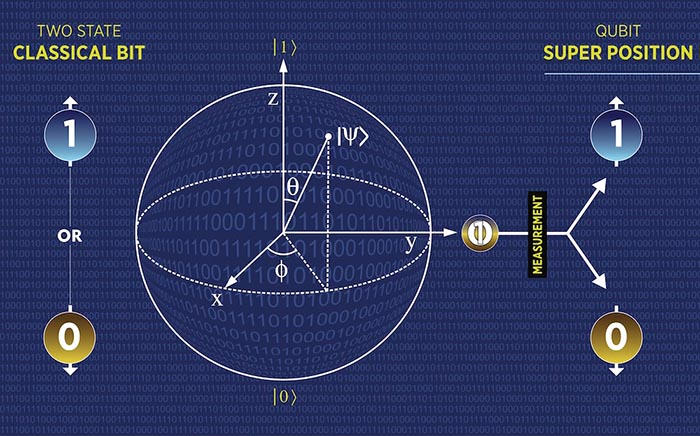

To flesh out these ideas into a fully comprehensible scientific theory, Faggin has worked with the physicist Giacomo Mauro D’Ariano [/], a world expert in quantum information. Quantum information is based on ‘qubits’ which can take on an infinity of different values. This is a huge contrast to the binary ‘bits’ on which computer systems are based, which are severely limited (zero or one; on or off). The information you are reading on the screen in front of you right now is made up of lots of such bits. Likewise, the information quantum physicists work with is limited to what can be expressed in bits, and so their measurements and models necessarily cannot fully express the richer quantum reality they study and represent.

If a quantum system is filled with qubit information that in principle cannot be fully known by anyone outside it, what is the point of it? After all, information informs, and if quantum information cannot be fully communicated to the scientists who are working with it, who or what can be informed? The answer has to be the quantum system itself (p. 242). D’Ariano and Faggin’s bold assertion is that quantum systems are self-aware: they are conscious. In fact, they go further and argue that consciousness is a quantum phenomenon.[3] Their work has led them to conclude that ‘the phenomenology of a conscious experience is that of a pure quantum state as both are “irreproducible yet knowable to the system feeling it”’ (p. 167). In this way, they explain one of the great mysteries of quantum mechanics, which is its unpredictability (Is Schrodinger’s cat alive or dead?). Of course, quantum behaviour is unpredictable because a key characteristic of a conscious entity is that it has free will. It is also aware of its surroundings and will respond to the information it receives from other conscious entities, such as whether it is being observed. Hence the puzzling behaviour of quantum phenomena becomes explicable and understandable.

The difference between ‘bits’ and ‘qubits’ is that while bits have only two possible states, qubits exist at the level of quantum reality in an infinity of possible states. But when they are subject to measurement they appear in the physical world in one of two states. Image: Vallabh Soni/Shutterstock

Knowledge of ‘That’ and Knowledge of ‘How’

.

If we accept that a quantum entity knows things in itself that the outside world in principle cannot, what is the nature of what it knows? What is the extra ‘something’ that quantum information contains that classical, bit-based, information cannot portray? D’Ariano and Faggin’s answer is that it is meaning – what they call ‘semantic’ rather than merely ‘symbolic’ meaning.

Understanding the difference between these modes of knowing is perhaps difficult for the speaker of English in a way that it is not for the German, the French or the Italian. In these languages there are two words for ‘to know’: in German kennen and wissen, in French connaître and savoir, in Italian conoscere and sapere.[4] The first of each pair refers to knowing through experience; the second to that which is known indirectly by being told or by reading about something. I can tell you that a suitcase weighs 25kg and so you wissen that it is heavy. Then you try and pick it up and now you kennen – comprehend – how the suitcase ‘really’ is heavy. Tellingly in German science is named Wissenschaft.

Experiential knowledge is far richer than anything a book can teach you. In picking up the suitcase, heavy becomes meaningful. ‘Without meaning, information is useless’, Faggin writes (p. 83). Indeed, another way of reading this book is that it is Faggin’s heartfelt plea for us to properly acknowledge the essential importance of ‘semantic’ information. Science, as the German name betrays, can only give us meaningless symbolic information. He writes:

Scientists […] with their intellect […] have separated the symbol from its meaning and have called reality only the symbolic information. […] Today science is only about symbols [while] spirituality is about meaning. […] If we fail to comprehend the insurmountable difference between symbol-without-meaning and symbol-with-meaning, we confuse the imitation of reality with reality. […] Ontology exists only in the semantic-symbolic reality that cannot be separated. (pp. 198–200)

For information to be comprehended as meaningful, consciousness is needed, he explains. Computers can only recognise symbolic information, so AI machines can never experience meaning.

The Building Blocks of Consciousness

.

Faggin offers a detailed and cogent account of how the basic consciousness, the One which he believes quantum science points to, has evolved to appear as ourselves and the world around us. The ultimate building block of reality is what he terms a ‘seity’, which he defines as ‘a self-conscious entity that can act with free will’ (p. 171). In understanding what he means here, caution is advised. The temptation can be to think of the seity as a ‘thing’ and calling it a ‘building block’ is misleading if this is not understood as a metaphor. A seity is no more material than our own thoughts are, but rather it is the state of a quantum field. This quantum field is itself a product of the universal field, One. He uses a useful analogy, likening individual seities to waves on an ocean: each has an individuality yet is not other than the ocean (p. 226).

A seity, then, is a part of One, the universal field which Faggin takes to be the very ground of being. He acknowledges that this is an assumption, recognising, as philosophers do, that all explanations, including those of mathematics, ultimately rest on premises or axioms that themselves cannot be proven (p. 24). He allows himself just one – one miracle – which is the existence of One (p. 175). This is in contrast to classical science which, as pointed out above, needs a great many more, and so he could appeal to the principle of Occam’s razor – that is, that if you have two competing ideas to explain the same phenomenon, you should prefer the simpler one – to support his vision.

Although perhaps he does make a second assumption because he muses that:

There must also be a reason that justifies the presumed existence of seities, and the most sensible one I can imagine is that One desires to know itself. […] Knowing must therefore be ontological and each new existence, which I have called seity, will be a part whole of One with the same desire, capacity, and freedom to know itself that One has. (p. 187)

So, how is the reality with which we are most familiar constructed from seities? I will attempt to explain briefly using metaphors and inevitably doing less than full justice to Faggin’s detailed account.

Think of the most primitive raw seities as if they are moving around, encountering other seities, communicating with them, all driven by curiosity and the desire to know more. They can only share symbolic information, just as that is all I can do with you. But, nevertheless, every encounter is enriching. On the one hand, each seity strives to express its interior, private consciousness to others, while also doing its best to interpret what it gather from others meaningfully. Seities therefore learn from one another and do so cooperatively. They can meld to form a new, unified seity with greater abilities, made possible according to the mysterious (for classical physics) phenomenon of quantum entanglement (p. 227). There is progress; experience is a teacher and new knowledge can be exploited in creative, unforeseeable ways. As Faggin puts it: ‘[Natural] laws gradually and spontaneously emerge from the communication of the seities to symbolically express the ever-deeper meanings that emerge from within through the process of conscious comprehension’ (p. 192). Guided by their self-created laws, seities discover new symbolic means of communicating through inanimate ‘objects’.

All that the seities discover is knowledge, and this knowledge is shared with One. In this schema, One is not all-knowing. While One knows all that has ever happened and can be known of the past, One cannot know the unfolding future. The seities are therefore creative and what is created through them cannot be known beforehand by One. ‘There is becoming in the universe which cannot be predicted by any equation or algorithm’ (p. 240). Even One cannot know whether Schrodinger’s cat is dead or alive until (in the future) we open the box.

Evolution continues: seities, through exchange of information and further merging, create an ever-richer way of expressing their interior consciousness through exterior symbols – the emergence of life. With life comes a new type of information which Faggin calls ‘live information’. An integrated combination of matter, energy and (conventional) information, this enables (and explains) the transformations that go on continually within living cells. ‘I am convinced that the study of [live information] will play a fundamental role in the understanding of life’, Faggin writes (p. 91). Incidentally, it becomes clear in reading this book that what classical biologists can achieve is limited; the future of biology lies in the emerging discipline of quantum biology.

Finally, seities evolve to the human, a seity with an outer bodily form, which can communicate and gather knowledge in hitherto (literally) unimaginable ways. Human seities develop new symbolic ways of exchanging information (language) and novel ways of recording it (writing) which can aid the search for meaningful knowledge. Furthermore, our body and our tones of voice (prosody) offer means of expression beyond that which words alone can achieve (it is said that less than 10% of what we communicate when we speak is through the words we utter). Furthermore, seities as humans are able to ‘use poetry or music to find a deeper expressive capacity in our ordinary symbols, allowing us to translate what we feel by going beyond the ordinary limits of classical symbols’ (p. 230).

Space and time in his model are emergent, and not primary, features of reality. But ‘becoming’ is ceaseless. As humans, seities have created ‘machines, computers, artificial intelligence and robots that would allow […] the dramatic extension of the range of virtual realities that the seities could eventually explore’ (p. 233). ‘Could’ but might not because he also warns that ‘there is the real danger of letting ourselves be seduced by the spreading culture of digital ontology and digital consumerism that replaces true and profound relationships with virtual and superficial ones, thus halting, if not reversing, our spiritual development’ (p. 292).

With the kind permission of J S Pailly

Final Thoughts

.

Faggin set off searching for an explanation for his extraordinary spiritual experience. The theory he sets out here does this. It tells us that his and our true reality is as an aspect of the universal consciousness. Bernard Kastrup has hailed this book as ‘in some ways, a culmination of Western thought’ (see back cover). This is indeed how it can be seen because Faggin has exploited the most advanced Western thought (quantum physics) while revealing its profound limitations. He has shown how sterile our current Western science is. The failure to acknowledge free will, to explain the origins of consciousness, life and natural laws cannot any longer be ignored. The environmental and ecological crises we face testify to this.

This book is a culmination also in that Faggin shows how further ‘thought’ has to be radically different. There needs to be a gestalt switch: consciousness not matter is primary; search for meaning not symbols, kennen rather than wissen. The implications of this is significant; for instance, it would mean changes in the curricula of our schools and universities, and an end to the obsession with STEM subjects, instead revaluing the humanities. We owe this to our young people.

Faggin understands that his vision is far from being wholly novel. On the contrary, he acknowledges that ‘[it] is deeply aligned with the thinking of perennial philosophy which has always recognised the inestimable value of consciousness and knowing’ (p. 255). For example, these words could have been written by him: ‘Everything starts with a single element, namely the One, but the first thing that emanates out of the One is consciousness.’ But these are not his words but those of Professor Stefan Sperl describing the principles of Neoplatonism in an article in Issue 22 of Beshara Magazine. In this, Sperl shows how Neoplatonism has influenced thinkers and poets throughout the ages and continues to do so. Faggin’s contribution is to set this ancient philosophy within a world where science has revealed so much and within which it plays such a prominent role.

There is a deep irony in Faggin’s book. It is after all a book full of symbols, the very symbols which he has critiqued. The truths he wants us to know will therefore require more than reading what he has written and perhaps nodding assent. So, he concludes with this wisdom:

Only the heart makes it possible to unite the inner and the outer worlds so that being and knowing become one; a world in which science and spirituality will finally be able to integrate, allowing humankind to comprehend what love is by becoming love and joy and peace. (p. 286)

Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature was published by Essentia Books in 2024.

Irreducible: Consciousness, Life, Computers and Human Nature was published by Essentia Books in 2024.

Sources (click to open)

[1] FEDERICO FAGGIN, Silicon (Waterside, 2021).

[2] BILL BRYSON, A Short History of Nearly Everything ( Doubleday, 2003), Chapter 19.

[3] G.M. D’ARIANO & F. FAGGIN, ‘Hard Problem and Free Will: An information-theoretical approach’, in Artificial Intelligence Versus Natural Intelligence (Springer, 2022), pp. 145–92.

[4] See PHILIP GOFF’s account of Black and White Mary in his book Galileo’s Error (Rider, 2019), pp. 71–5, which illustrates the same distinction between these two types of knowledge. IAN McGILCHRIST also draws attention to the absence of two words for ‘know’ in English, see The Matter with Things, (Perspectiva, 2021) p. 631, and Faggin himself on p. 197.

Dr Richard Gault has worked at universities in Scotland, Ireland, The Netherlands and Germany, where he has taught and researched a variety of subjects, including the history and philosophy of science and technology. He is a long term student of the Beshara School and from 2015–17 was principal of The Chisholme Institute in Scotland.

read more in beshara magazine

More News & Views

Don’t Take It Easy

Richard Gault is inspired by Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis and explores the idea of ‘misogi’ during a 600-mile walk across Scotland

Book Review: ‘The Serviceberry’

Martha Cass contemplates the message of a new book by Robin Wall Kimmerer that advocates ‘an economy of gifts and abundance’

Book Review: ‘Conversations with Dostoevsky’

Andrew Watson engages with an innovative new book by George Pattison which explores Dostoevsky’s relevance in the contemporary world

Thich Nhat Hanh & the Poetry of Engaged Buddhism

Philip Brown presents the poem ‘Recommendation’ and comments on the potential of contemplative art to foster compassion

Introducing… ‘Perfect Days’ and ‘Nowhere Special’

Jane Clark watches two films with a contemplative theme

An Irish Atlantic Rainforest

Peter Mabey reviews a new book by Eoghan Daltun which presents an inspiring example of individual action in the face of climate change

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READERS’ COMMENTS

3 Comments

Submit a Comment

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

“Computers can only recognise symbolic information, so AI machines can never experience meaning.” So AI, if it exists, is pure left brain consciousness, with all that that implies (cf McGilchrist on the pathologies of right hemisphere damaged patients).

Federico Faggin’s model not only of consciousness but of Reality Itself (Plotinus’s “One”) is ambitious and highly detailed. And consequently can be expected to predict radical new experiences. One such outlandish prediction might lie in the direction of Nick Herbert’s Preposterous Proposition described at

http://quantumtantra.blogspot.com/2024/10/metaphase-typewriter-20-preposterous.html

Wonderful review. Faggin’s next book is out but only in Italian.

Interesantes temas. Felicito la iniciativa que publica ideas y actualidades con contenido referido y de interés científico, de aquel interés que ya ha reconocido las restricciones de la Ciencia como método para reconocer aquello que va más allá de la extensibilidad de la Consciencia, hasta adonde en la actualidad se encuentra.