Arts & Literature _|_ Issue 25, 2024

Poems of Hope and Light

Neil Astley, founder of Bloodaxe Books, talks about the universal appeal of contemporary poetry and the series of inspiring anthologies he has edited

Poems of Hope and Light

Neil Astley, founder of Bloodaxe Books, talks about the universal appeal of contemporary poetry and the series of inspiring anthologies he has edited

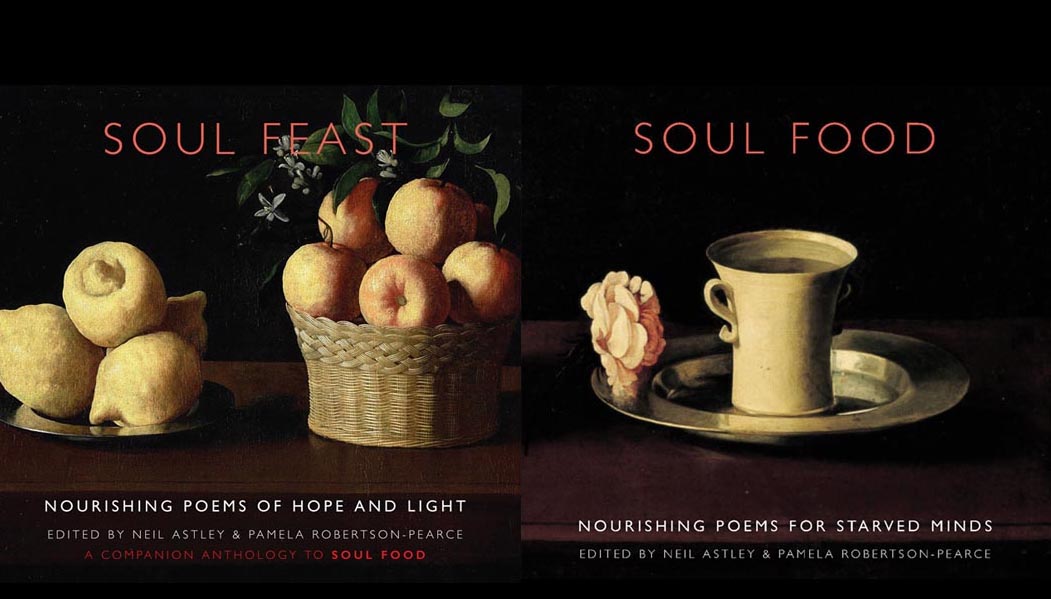

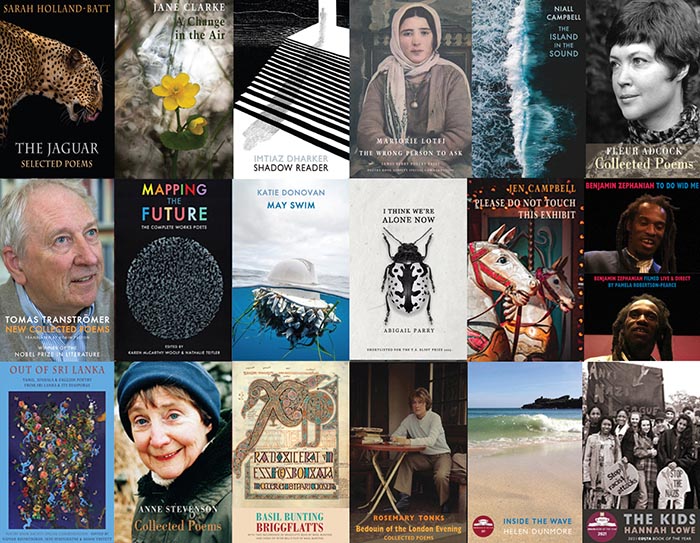

Bloodaxe Books [/] is one of the most influential and innovative publishers of poetry in the UK today. It has almost single-handedly been responsible for the dramatic increase in the readership for contemporary poetry over the last forty years, introducing many new writers of diverse background and ethnic origin. Its impressive list includes now well-known names such as Simon Armitage, David Constantine, Imtiaz Dharker, Bernardine Evaristo, Jane Hirshfield and Benjamin Zephaniah, and is unique in UK poetry publishing for its 75–25 female: male balance. Some of Bloodaxe’s best-selling books have been poetry anthologies with global scope – the Staying Alive series (2002–2020) [1] and Soul Food (2007) [2] which this year has been joined by a second volume, Soul Feast.[3] Neil Astley, the founder of Bloodaxe and still its only editor, talked to Jane Clark and Peter Huitson from his office in Hexham about the intentions behind Bloodaxe, and his latest anthology in particular. (Scroll down to the end of the article or click here. to hear readings by seven poets from Soul Feast)

Jane: Can we begin by asking how you came to do this remarkable thing of devoting your life to contemporary poetry?

Jane: Can we begin by asking how you came to do this remarkable thing of devoting your life to contemporary poetry?

Neil: I had various jobs in journalism after leaving school; I worked in the admin side of publishing for a time in London, and I ended up in Australia on a newspaper in Darwin. In 1975, after Darwin was destroyed by a cyclone, I decided to come back to England and get into publishing. I was much more interested in editorial than admin, so I thought I would need to take an English degree in order to do that. So between 1975 and 1978, I went to Newcastle University to study.

Before starting the course, I met the editor of Stand Magazine [/], Jon Silkin. He discovered that I’d worked in newspapers on the production side, and he needed a production editor part-time. So during my three years at university, I was also working for Stand, organising poetry readings and becoming very involved in the whole poetry scene in Newcastle. But when I left university, I fell out with Silkin, so I decided to set up a small press myself and this became Bloodaxe.

Jane: It was an unusual decision, maybe, not to go to London, which most people would have considered to be the cultural centre of the UK at the time.

Neil: Well, I decided that I wanted to build something in the North that would become a publisher in its own right, and I very much wanted to do something about poetry. At that time in the 70s, the poetry scene in Britain was quite moribund; very few women were published, and few writers of colour. It was also very parochial; there were not many American poets in print or poets in translation. I was very frustrated by what I saw in bookshops because it didn’t reflect my own sense, gleaned from live readings and poetry magazines, of what poetry was out there. There was a divide between what was going on at grassroots level and what was actually being published, and that’s what I wanted to break through.

Jane: So among the many authors that you discovered in the northern poetry scene was Simon Armitage, who is currently the UK’s Poet Laureate.

Neil: Yes, I published his first book Zoom in 1989, and then another, Xanadu, in 1992. But then he got poached by Faber & Faber, because in those days, anyone that we brought up tended to get poached by the big publishers. Within a few years, though, we had poets saying, no, I don’t want to go to another publisher, I want to stay with Bloodaxe. So now we have people who have remained with us for many years.

Peter: Why did you call the press ‘Bloodaxe’? Was it named after Eric Bloodaxe?

Neil; Yes. He was the last Viking king of Northumbria, which then covered the whole of the north of England, north of the Humber, up to Scotland. He figures in Basil Bunting’s long poem ‘Briggflatts’ [/],[4] which Bloodaxe publishes. There are two personae in ‘Briggflatts’; one is St Cuthbert from the holy side and the other is Eric Bloodaxe from the Viking side. Bunting always felt as though both parts of that inheritance were in him – in his own self. At the time when I was setting up my press, a lot of the cultural things going on in the area – magazines and art galleries and so on – were named after the holy figures of Bede, Ceolfrith and Cuthbert, etc. – and I felt it was time that the Vikings got a say.

Peter: We wondered if there was an aspect of fighting for the North.

Neil: Well, yes, it was also a symbol of independence, because after Bloodaxe the North became part of England; it was sort of annexed.

Contemporary Anthologies

.

Jane: We’ve already mentioned that you were instrumental in developing the careers of some of our most significant contemporary poets. The list of people Bloodaxe has published, which numbers nearly 500 now, reads like a celebrity A-list. But some of the most successful books that you’ve done are anthologies, which have been best-sellers by any standard. I’m thinking particularly of the Staying Alive series, which has four books in it to date, and now Soul Food and Soul Feast. How did you come to do these? And why do you think they have struck such a chord with people?

Neil: Well, in the late 90s, Arts Council England did a poetry readership survey which had some very interesting findings which were both frustrating and challenging to me as a poetry editor. They found, for example, that 95% of the poets whose books were sold in British bookshops were dead – meaning that 95% of the readership was not buying contemporary poetry – and also that two-thirds of the modern poetry collections sold in that year were by Seamus Heaney! Yet people were reading contemporary fiction or were going to theatre, and so on.

One of the problems was that poetry had a very bad image because of the way in which it had been taught in schools. People had the feeling that it was not for them; it was seen as irrelevant, highfaluting, airy fairy. And yet I knew that there were many poets around whose work readers would relate to if only they knew about them. People have this notion that poetry is something they can turn to at times of emotional extremes – death and love in particular – but there are so many other areas of life which poetry connects with; the problems of everyday living, and things like depression, anxiety, concerns about the planet, a sense of alienation. So I had the thought of producing an anthology that would include work addressing these areas.

So I put together a proof of Staying Alive, and I sent a hundred copies to various people in different fields whom I knew were poetry lovers from things that they’d said in interviews or in their work. So, for example, Brendan Kennelly, a great friend of mine, was also a friend of Mia Farrow and he was always talking about how Mia loved poetry. So I was able to write to her, as well as to various novelists and the film director Jane Campion, who used poetry in her films. The idea was to include figures who were culturally respected. I hoped that if they connected with the book, they would give us a comment. So when Staying Alive was published, we had a whole load of quotes on the back cover from those different people.

Peter: Was it immediately successful?

Neil: For the first printing, we thought we were ambitious in thinking we could sell 10,000 copies, but it sold out in two weeks, and we had to do another one immediately. It sold over a quarter of a million copies in the end. Then two years later, we did the next one, Being Alive and then in 2011, Being Human and then Staying Human just a few years ago, in 2020. These came about partly because of the response we got from readers. We received a lot of fan mail from people who loved the book and said: I was given this copy by a friend and now I’ve bought six more for my other friends. So there was a word of mouth effect. In a sense the book went viral before we really had the concept of going viral, which is a term associated with digital media.

At the same time, readers would send me copies of poems that they loved and which they wanted to share. And those fed into the next anthology. I discovered poets I hadn’t read before in this way, and at one stage, we actually put out an appeal for people to send us their suggestions. So, over the years, we’ve incorporated all the reader responses into the construction of the anthologies.

Jane: The books were obviously given a great boost by their association with celebrity names, but they would not have been so successful unless there was something about them which was fundamentally appealing. Do you think it was the fact that they were talking about everyday problems and situations about which people had not previously found a voice through which to express their feeling?

Neil: I think that was part of it. Yes. And partly that these are such great poems that people just connect with them if they manage to find them. We’ve had a lot of examples of poets telling us that someone came up to them at a reading who had come across one of their poems in an anthology, and immediately went out and bought their book. So anthologies can be a bridge for people who then go on to read the poets that they relate to. The whole way these anthologies have developed is an organic process which has happened in many different ways.

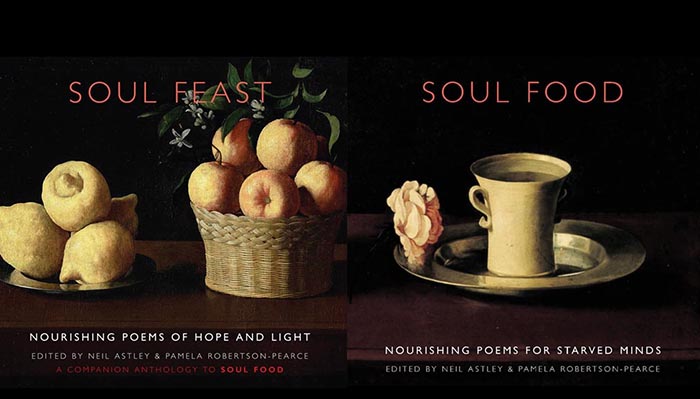

The best-selling Staying Alive series of anthologies, published by Bloodaxe books between 2002 and 2020.

Compiling Anthologies

.

Jane: I wonder about the process of putting together an anthology, rather than say, a book of new poems by an author. You have said that it is a matter of pairing different poems which address each other directly, or by picking up a theme or a phrase as composers do in music and orchestrating the selections in such a way as to bring the conversation to life.

Neil: I did not do this very consciously in Staying Alive, but it certainly took over in the subsequent anthologies, where part of the delight of creating the books was to find connections between poets or poems so that readers would read from one to another and find echoes, or chains of ideas and thoughts, developing.

There are occasions where the poems are actually addressed to another poet or are a response to another poem. So these are real connections, and there has, of course, been a very long tradition of poets riffing off each other. But sometimes I create those connections in how I do the selecting.

Jane: There is a lovely example of all this in Soul Feast in a sequence of three poems by Jorge Louis Borges, Peter Sirr and Lucie Brock-Boido. Borges’ ‘Poem written in Copy of “Beowulf”’ ends with the lines:

Beyond anxiety and beyond this writing

the universe waits, inexhaustible, inviting [5]

which Sirr quotes in Spanish at the start of his poem ‘A Saxon Primer’. This is a contemplation on Borges’ state when he wrote his poem – when he was going blind. He also picks up on another line, about which he writes:

It’s that the soul must know it is immortal,

he said, and its hungry turning circle

takes everything in, achieves all that’s possible.

There’s a kind of secret knowledge

enfolds us, reaches everything we do… [6]

and you have followed his poem by Brock-Boido’s ‘Soul Keeping Company’ which is about immortality and the body.

Neil: The idea was that making these connections would add to the overall appreciation not just of the individual poems, but of the whole experience of reading them.

Poems of Hope and Light

.

Jane: Jane Hirshfield – whom we interviewed for Beshara Magazine in 2022 (click here) – has said, in relation to a poem she wrote about 9/11, that poetry doesn’t do anything; it doesn’t have any political impact, and it doesn’t have a didactic role or carry a moral message, such that it would tell us how to behave. Yet it’s clear that it’s very, very important to people. For instance, at the beginning of the pandemic, everybody was sending each other poems and in the UK they were being read in the daily news programmes, etc.

Neil: People always quote that line of Auden’s in ‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’: ‘poetry makes nothing happen’. And yet it does make something happen in people themselves – in how they are in their being, in how they deal with things, whether they are personal situations, or shared situations with a whole nation or the whole world.

One of the things highlighted in the Soul Food/Soul Feast books is hope. The subtitle is ‘Nourishing Poems of Hope and Light’. But it’s been the theme of all the anthologies. Staying Alive includes Brendan Kennelly’s poem ‘Begin’ [/], which was circulated among Irish Americans immediately after 9/11. And Adam Zagajewski published a poem in The New Yorker called ‘Try to Praise the Mutilated World’ [/], which also connected with people at that time. So there was a way in which those two poems in particular resonated with the experience of the Americans who’d just gone through 9/11, so that they didn’t feel so alone, that there was hope, that there was a way forward.

Peter: At the beginning of Being Alive, you say that good poems don’t just offer simple solace or ‘poetic medication’. Rather they disturb us, they bring us to question or look more deeply, make us less settled. You relate this also to wholeness; that through reading a poem, we somehow become more whole, more complete.

Neil: Yes, that’s certainly true, I think. Yes.

Talismanic Poems

.

Jane: One of the ideas you have introduced me to is that of ‘talismanic’ poems. These are the sort of poems that people keep in their wallets or on fridges and give to friends or read on special occasions. They somehow capture the psychological or spiritual zeitgeist.

Neil: This is actually how Staying Alive started. The first set of poems I chose were ones that I or my friends had on fridges or always carried around with us. There was a core of about 20 that I immediately identified, and the more I thought about that particular sort of poem, the more I could immediately spot them when I was looking through books to make the rest of the selection. It’s odd, you know, how when you read a whole collection by a poet, you can just come upon one poem like that and say, yes, that’s it. It’s clear that none of the other poems in the whole book will serve.

Sometimes I’ve had poets say to me, why did you include that poem in the anthology? It’s not really representative of my work. I’d much rather have you include such and such a poem. Even when trying to get rights cleared, we’d have poets coming back saying they would much rather have another poem than the one we picked. But we’d have to say no, it has to be that poem – it’s that one that will speak outside of its existing context to so many other readers. I’ve even taken poems from books I’ve rejected. A manuscript has come in and I’ve read it through and apologised for not being able to take it on. But there’s been one poem that I’ve really loved, and I’ve kept a copy of it. Then years later I’ve written to the poet, to their great surprise, asking whether we can include it in an anthology.

Peter: Nowadays you choose works from a variety of countries, a huge range of classes, cultural backgrounds and different literary traditions. In the introduction to Being Alive, you mention that one of the reasons is that they can surprise us because they have a different voice or a style or angle of approach.

Neil: A great example of that is the poem ‘Table’ by the Turkish poet Edip Cansever, which is in Soul Feast. When I’ve done workshops with poets, I often start off by reading that poem as an opening without saying who it’s by. Everyone goes ‘Wow’ at the end, and then I tell them that this poem was written in the 1950s by a Turkish poet, and that for Turkish readers, it’s a talismanic poem. It’s such an amazing poem and it does the kinds of things that you don’t get in English poems. Now it’s been appearing in a number of other anthologies, and it’s got a circulation out there beyond Bloodaxe. I read the rest of his work in translation, and there wasn’t another poem that was like it in that way.

Table

A man filled with the gladness of living

Put his keys on the table,

Put flowers in a copper bowl there.

He put his eggs and milk on the table.

He put there the light that came in through the window,

Sounds of a bicycle, sound of a spinning wheel.

The softness of bread and weather he put there.

On the table the man put

Things that happened in his mind.

What he wanted to do in life,

He put that there.

Those he loved, those he didn’t love,

The man put them on the table too.

Three times three make nine:

The man put nine on the table.

He was next to the window next to the sky;

He reached out and placed on the table endlessness.

So many days he had wanted to drink a beer!

He put on the table the pouring of that beer.

He placed there his sleep and his wakefulness;

His hunger and his fullness he placed there.

Now that’s what I call a table!

It didn’t complain at all about the load.

It wobbled once or twice, then stood firm.

The man kept piling things on.

(Translated by Julia Clare Tillinghast & Richard Tillinghast) [7]

There’s also a Beshara connection I should mention. Cansever’s co-translator, the poet Richard Tillinghast, told me he remembered the day about thirty years ago when his Turkish conversation teacher in Istanbul brought the poem into the class. Richard immediately translated it with a little help from a Turkish friend for one or two phrases. It read so plain that he wondered it if could ‘really fly’ in English.

He also said that Reshad Feild [/] was an old friend of his, and he met Bulent Rauf [/] (the first consultant to the Beshara School), in Istanbul years ago, who would discourse with a small circle at the courtyard opposite the Küçük Ayasofya mosque. The philosophy of Ibn ‘Arabi was of particular interest to them.

Jane: A notable feature of Soul Feast is the number of poems in translation. You are clearly not afraid of including these. And I find that there is a strange paradox here which perhaps sheds more light on the nature of poetry. A poem is such a particular linguistic expression – in a way, the very essence of poetry is mastery of a particular language. And yet poems do work in translation – providing that they have the right translator, of course.

Neil: Translations work because poems are universal. What’s going on in a poem – the experience it describes – is universal. So even though linguistically it may not be as authentic as the poem in its original language in terms of what the poet says and how they say it, a translation can still capture the meaning.

Something else we wanted to do with Soul Feast was to give much more background on the poets. In the Staying Alive series, each section is contextualised, but in the Soul Food anthologies the idea is that you read the poem at the front and then you can go to the back and find out more about the author and the context in which it was written. And I think that adds greatly to people’s appreciation of it.

Obviously I knew already the background of many of the poets before we made our selection, but even so, a lot came out of our research. I didn’t know, for example, that Ai Qing, the Chinese poet who wrote the poem ‘The Lamp’ in Soul Feast – a poem I really love – was the father of the artist, Ai Weiwei, and that he wrote it while they were both imprisoned in a labour camp.

Jane: It seems to me that knowing something about the lives of the poets adds not only to our appreciation of the poems themselves, but also to the sense of universality you have just mentioned – the fact that people from such a diverse range of backgrounds and life experiences can nevertheless communicate with each other at a profound level.

Soul Food and Soul Feast

.

Peter: You’ve mentioned one difference – a technical difference – between the Soul Food and the Staying Alive series. But is there a more fundamental difference in the intentions behind them?

Neil: Well, they are both aimed at a wide audience, but I think they go to different readerships, or maybe have different functions. I know people who’ve kept Soul Food by their bedside or they travel with it because of its size. It just slips into a pocket or a travelling case. They are much more travel books than the big ones, which are quite heavy to carry; they contain just 100 poems, whereas the Staying Alive series all have 500.

The other thing to mention is my co-editor on the Soul Food series, Pamela Robertson-Pearce, who is my wife. The selections include a lot of her favourite poems which she has gathered over the years. She’s Swedish, but she lived in America for 20 years, and so she’d come across a lot of poets and poems in America that I didn’t know about. And so she was able to feed those into the selection process, whereas the Staying Alive books are all just chosen by me.

Peter: I also notice that you tend to keep the poems short, usually less than one page. I know there are some exceptions, such as Dennis O’Driscoll’s ‘Fabrications’, which I think is a wonderful poem, that goes on for four pages. But the short length of most of them does make it easier to just turn to the book when you feel the need for whatever it gives you.

Neil: Yes, you can go back and re-read these poems over and over again because they offer so much even though they are short. You get more from them each time, and I think if you read the little notes on the poets as well, they add further depth.

Peter: I also like the fact that you’re not scared to include poems that explicitly mention God. Sometimes, in modern poetry collections, people tend to steer away from that.

Neil: Yes indeed. There’s an odd relationship with God in many of these poems. There are poets who are believers, and whose poems speak directly about that. And there are poets that are questioners without being believers and yet somehow connect with that same spiritual conversation. And so there is a mixing of the two. You mention Dennis O’Driscoll’s wonderful poem about living in a society where God has kind of disappeared for many people. I’ve used a number of his poems in the different anthologies, and I think he really speaks to that situation for a lot of people, particularly in Ireland.

God is dead to the world

But he still keeps up

——appearances. Day after

day he sets out his stall.

——Today his special is

A sun-melt served on

——a fragrant bed of

moist cut-grass: yesterday

——a misty-eyed moon… [8]

Bloodaxe book covers

Changing Times

.

Jane: Staying Alive came out in 2002 and Soul Feast just a month ago, in 2024. Do you feel that our concerns have changed in the intervening 20 years, and if so, how is this reflected in the choices you have made for Soul Feast?

Neil: I think one of the differences between Soul Feast and Soul Food is that Soul Feast is in many ways more worldly. There are also areas like ageing and tolerance that we felt would chime with these poems, so there are several relating to that. And also poems about gay and lesbian experience – about how people deal with that within families, parents either approving or not approving the sexuality of their children. This was an area that wouldn’t really have come up in quite that way in 2007.

And of course there’s the environment – the catastrophe of environmental destruction – on which I included a whole section at the end of Staying Human, and there is also a sequence of half a dozen poems in Soul Feast relating to it. This is much more on our radar now than 15–20 years ago, and in a sense, it is now a spiritual issue because it’s all about our relationship with the Earth.

The Russian poet Maria Stepanova, at a recent event launching her new book, Holy Winter (see video right or below) said that she thinks that incomprehension is a big issue at the moment.[9] People can’t grasp what’s going on in the world. How can we deal with the world that we now have, that just seems to be getting worse and worse?

Video: Launch Reading of Jane Hirshfield and Mara Stepanova; Duration: 1:38

Jane: This takes us back, perhaps, to your original statement about the underlying message of Soul Feast being hope. You’re not yet in despair about what’s happening in the world?

Neil: Well, I think that although things do seem hopeless in many ways, the poems tell us that we’ve got to hope, we’ve got to hang on. In the recent discussion I just mentioned with Jane Hirshfield and Maria Stepanova, we talked about how, individually, we can hang on in our own lives; we may not be able to change things more broadly, but we can still try and work within ourselves and with our family and friends to create some kind of hope in the way we live.

Jane: So talking of hope for the future: what is coming next for Bloodaxe?

Neil: Well, there’s nothing more on the anthology front at the moment, but we’re going to be doing a Benjamin Zephaniah book next year. The intention is to pull together all his books of poetry, because there was such an outpouring of love for him when he died last year, and loads of people asked us when we were going to do a collected works because they would love to have it to remember him by.

Jane: Neil, thank you so much for talking to us about the truly valuable work you have done over the years in drawing out these poems, which do indeed bring us nourishment, hope and light. Could we ask you one final question: if you had to choose one poem from Soul Feast which you feel really addresses the issues of our time, what would it be?

I think that’s almost impossible. I might pick out Lisel Mueller’s ‘Hope’ as poem of hope or Tuvia Ruebner’s ‘Wonder’ as a poem of light in times of darkness. But as far as specific issues of our time are concerned, then I’d have to go for Marie Howe’s ‘Postscript’, which was a very late addition when we thought the anthology was complete. We read it in a magazine last summer and immediately asked if we could include it. It’s going to be in Marie’s first UK poetry book from Bloodaxe later in the year.[10]

Postcript

What we did to the earth, we did to our daughters

one after the other.

What we did to the trees, we did to our elders

stacked in their wheelchairs by the lunchroom door.

What we did to our daughters, we did to our sons

calling out for their mothers.

What we did to the trees, what we did to the earth,

we did to our sons, to our daughters.

What we did to the cow, to the pig, to the lamb,

we did to the earth, butchered and milked it.

Few of us knew what the bird calls meant

or what the fires were saying.

We took of earth and took and took, and the earth

seemed not to mind

until one of our daughters shouted:

.

The air turned red. The ocean grew teeth.[11]

The Bloodaxe Books website bloodaxebooks.com is a treasure trove of open-access information about the poets that they publish as well as many videos of readings and events.

In the video below, some of the poets featured in Soul Feast read their poems.

Video: Seven poems from Soul Feast read by the poets. Duration: 11:28

Image Sources (click to open)

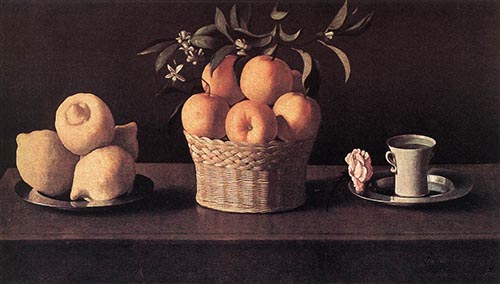

Banner Image: The book covers of Soul Food and Soul Feast. They are each taken form Still Life with Lemons, Oranges and a Rose (1633) by Francisco Zurbarán, and when placed side by side reproduce almost the complete image.

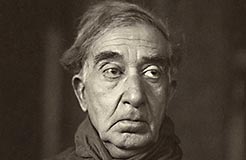

Insert: Neil Astley, courtesy Pamela Robertson-Pearce.

Our thanks to Bloodaxe Books for allowing us to use images from their excellent website.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] Staying Alive, edited by Neil Astley (Bloodaxe Books, 2002). Being Alive, edited by Neil Astley (Bloodaxe Books, 2004). Being Human, edited by Neil Astley (Bloodaxe Books, 2012). Staying Human, edited by Neil Astley (Bloodaxe Books, 2020).

[2] Soul Food, edited by Neil Astley and Pamela Robertson-Pearce (Bloodaxe, Books, 2007).

[3] Soul Feast, edited by Neil Astley and Pamela Robertson-Pearce (Bloodaxe Books, 2024).[4] Basil Bunting, Briggflatts (Bloodaxe Books, 2009) (Paperback + CD + DVD).

[5] Jorge Luis Borges ‘Poem Written in a Copy of “Beowulf”’, translated from the Spanish by Alastair Reid, in Soul Feast, (Bloodaxe Books, 2024) p. 38.

[6] Peter Sirr, ‘A Saxon Primer’, ibid., p. 39.

[7] Edip Cansever, ‘Table’, translated by Julia Clare Tillinghurst and Richard Tillinghurst, ibid., p. 106.

[8] Dennis O’Driscoll, ‘Fabrications’, ibid., p. 31.

[9] Maria Stepanova, Holy Winter 20/21, (Bloodaxe Books, 2024).

[10] Marie Howe, What the Earth Meant to Say: New & Selected Poems (Bloodaxe Books, 2024) (Forthcoming).

[11] Marie Howe, ‘Postscript’ in Soul Feast, (Bloodaxe Books, 2024) p. 66.

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Launch Reading of Jane Hirshfield and Mara Stepanova; Duration: 1:38

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Personal Integrity in the Poetry of C.P. Cavafy

Andrew Watson pays homage to Greece’s most famous modern poet, whose message of quiet fidelity to one’s own values still has great resonance today

Conversations with Jane Hirshfield

Jane Clark and Barbara Vellacott talk with the distinguished poet about her latest work and the role of poetry in these difficult times

George Swede: Haiku Master & Secular Contemplative

Robert Hirschfield talks to the Canadian poet and psychologist

Poems for These Times: A Reflection

Jane Clark and Barbara Vellacott review the poetry series we presented during the Covid-19 lockdown, March – June 2020

READERS’ COMMENTS

I really enjoyed hearing the Poems read by the authors. I don’t often read poetry but listening to them like this really brought them alive.

Thank you Jane

I loved this interview. What a story….and what faces… I’m off to buy Hope and Light right away.