A Thing of Beauty…

Barbara Vellacott contemplates the indescribability of beauty in Dante’s ‘Paradiso’

A THING OF BEAUTY…

Barbara Vellacott contemplates the indescribability of beauty in Dante’s ‘Paradiso’

The ‘Divine Comedy’ by Dante Alighieri is regarded as a masterpiece of world literature, depicting the spiritual journey of the soul from the depths of hell (Inferno) through a process of purification (Purgatorio) to the heights of heaven (Paradiso). In the first two books, Dante is guided by the Roman poet, Virgil, but in ‘Paradiso’ he is led by his ideal woman, Beatrice, who takes him through the nine celestial spheres into the very presence of God. Here Barbara Vellacott, a teacher of poetry, contemplates the way that Dante, and the later artists who illustrated the poem, allude to the realms of divine beauty which are beyond all concept and image.

The beauty that I saw transcends

all thought of Beauty… (XXX, 19-20)

This is Dante’s exclamation as he turns his gaze on Beatrice, his guide to Paradise and the embodiment of divine beauty. He declares himself defeated in his poetic endeavour:

for, like sunlight striking on the weakest eyes,

the memory of the sweetness of that smile

deprives me of my mental powers. (XXX, 25–27)

The beauty is indescribable.

In his journey through the spheres of Paradise, with Beatrice leading him, Dante reaches a higher level of vision – he sees a river of light. Take a moment to imagine this… a torrent of pure light, with living sparks scattering from it and settling on the flowers on its banks. The sparks and flowers are angels and blessed souls. Then the river changes into a circular sea of light.

O splendour of God, by which I saw

the lofty triumph of the true kingdom,

grant me the power to tell of what I saw. (XXX, 97–99)

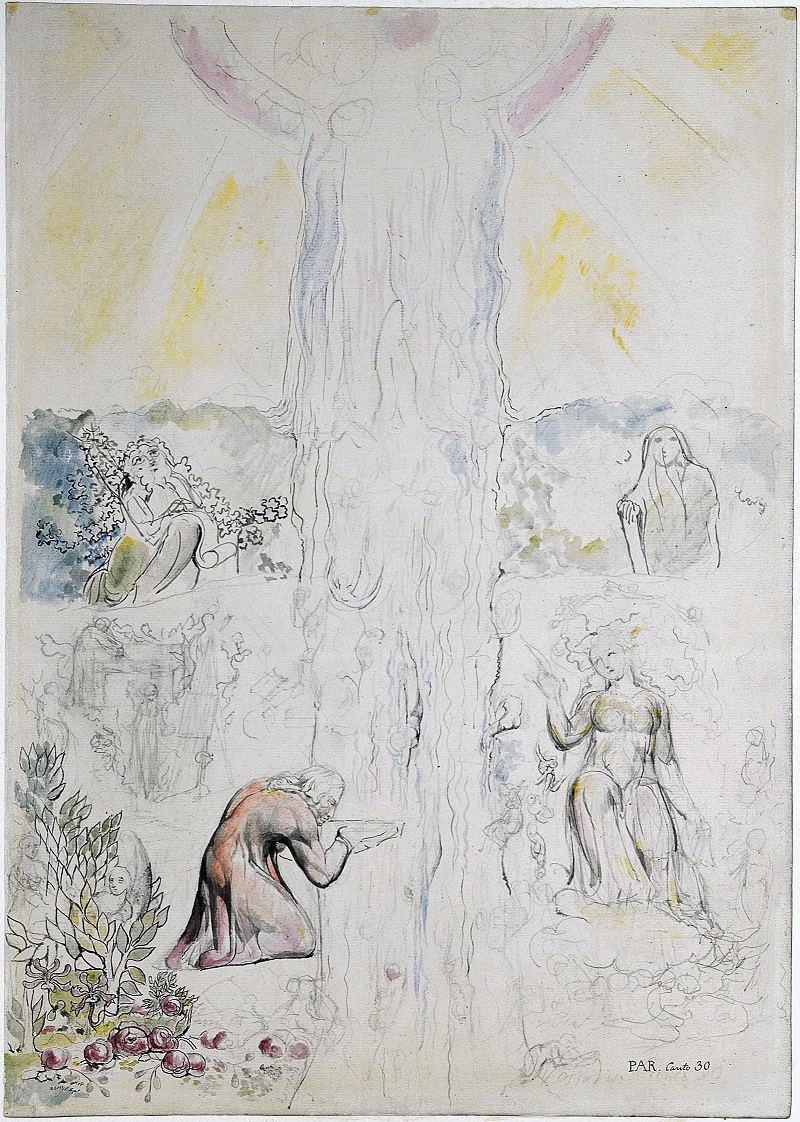

Illustration to Canto XXX, by William Blake. Dante and Beatrice in the Empyrean Drinking at the River of Light. The Tate Gallery, image via Wikimedia Commons.

Earlier, in Canto XXIV, the blessed souls dance like bright flames around Dante and Beatrice; the brightest of them, St Peter, circles round Beatrice three times…

its song so filled with heavenly delight

my phantasy cannot repeat it.

And so my pen skips and I do not write it,

for our imagination is too crude, as is our speech,

to paint the subtler colours of the folds of bliss (XXIV, 23–27)

Over and over again, in the Divine Comedy as a whole, and especially at the height of Paradiso, Dante tells us that he cannot describe what he sees, and yet in so saying he writes supreme poetry. Such poetry takes the willing reader into the experience of splendour and into the heart of beauty.

How can we describe beauty – the beauty of anything? We simply exclaim: “It’s beautiful!” Beauty itself is in the experience, and relating it is the act of reflection afterwards, when often we say, “I can’t describe it.”

In writing Paradiso Dante is re-imagining an experience he apparently had many years before, so it is necessarily related to memory, as he himself recognised. In the final canto he invokes the divine Light again:

O Light exalted beyond mortal thought,

grant that in memory I see again

but one small part of how you then appeared

and grant my tongue sufficient power

that it may leave behind a single spark

of glory for the people yet to come. (XXXIII, 67–72)

And later:

O how scant is speech, too weak to frame my thoughts,

compared to what I still recall my words are faint. (XXXIII, 121–122)

So, when I try to write about my own moment of excitement in reading Paradiso, that sequence is echoed: I read (aloud), experience the music of the poem, ‘see’ the river of light with a surge of exaltation. “That’s beautiful!” I think. In a weak parallel to Dante’s impulse to tell the glory for the people yet to come, I may want to tell someone, or, as I did some time later, read these last cantos to a friend in a care home whose attention was riveted and whose eyes lit up as she heard the poetry. “That’s wonderful!” she said.

And so the beauty experienced by the poet and expressed in the poem continues vibrating as we read it, revisit it, share it, and, I hope, as I write now. Let us say that beauty is a divine vibration which sings in poet, poem, reader and listener. But its essence is nevertheless indescribable, and the supreme vision must in its very nature be so.

Illustration of Canto 15 by Giovanni di Paolo. Dante and Beatice ascend to the sphere of the sun. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Visual artists and Paradiso

It is interesting that when illustrating the Divine Comedy, visual artists are usually much more ready to depict the horrors of hell than the ineffable beauties of Paradise. To convey transcendence, ecstatic movement or a realm beyond time and space must be a challenge to the artist. What do these states look like?

However, there are artists who attempt to paint Paradiso. Giovanni di Paolo (c.1400–1482) does detailed miniature illustrations of scenes from Paradiso, with illustrated capitals for the text. At least to a modern eye, Paradise here seems very describable – is it too literal to match the spiritual realities of the poem? Perhaps we can sense that the lavish use of pure gold, often on a background of rich blue, does convey the glory of ineffable vision. Can pure gold take us straight to the mystery of supreme Light? One simply speculates about the effect on contemporary readers of these exquisite images.

Botticelli (1445–1510), having detailed Inferno and Purgatorio, also depicts Paradise with a visionary delicacy in his series of drawings of the Divine Comedy. These convey a sense of breathing different air and of weightlessness. But for Canto XXXII, in which Dante sees the vast and beautiful Celestial Rose holding all the redeemed souls, it seems that he gave up the struggle for adequate representation, showing only the figures of Mary, Christ and the archangel Gabriel – all tiny, and in the farthest distance.

Another visionary artist, William Blake (1757–1827) in his watercolours of Paradiso, achieves a ‘luminous joy’; the paintings seem to be made out of pure light (see above). And the contemporary artist, Monika Beisner, has lovely mandala-like paintings, like the one of Dante and Beatrice rising towards the Celestial Rose (see below). Such paintings are things of beauty in themselves and convey the ecstatic quality of that which is beyond description.

Illustration of Canto XXXII, by Sandro Botticelli. The Empyrean: St. Bernard of Clairvaux Explains the Divisions of the Celestial Rose; Dante’s Vision of the Virgin Mary.

Moments of vision

Why then do we even attempt to describe the beauty that is indescribable when we know that it is so? This brings us back to reflection, and the memory of moments of vision that are gone. Such moments leave their trace and we are not as we were. We make them real to ourselves by trying to describe them – “I saw….”, “I felt…” – and in the process bring the indescribable into form, into time and space, and go on refashioning it in imagination so that it grows in us. And we may want to write or speak about it, at first hesitantly then perhaps more formally in poetry or art. This must surely be the process of all mystical art.

The extraordinary thing about Dante’s Paradiso is the sustained nature of this visionary poem – thirty-three cantos with nearly 150 lines in each. In the vision there is a long journey, much movement, and theological discourse – no mere visionary moment you might think. And yet all this may have sprung from one moment of mystical experience containing eternity and infinity. There is a sense of rising ecstasy in Dante’s claim:

for my sight, becoming pure,

rose higher and higher through the ray

of the exalted light that in itself is true. (XXXIII, 52–54)

William Blake, in Milton, also writes of this visionary moment which contains everything;

In this period the Poet’s Work is Done, and all the Great

Events of Time start forth & are conceived in such a Period,

Within a Moment, a Pulsation of the Artery

Here is a last question about the indescribability of beauty in Paradiso: the essence of beauty may be indescribable, but wherein lies the beauty? What are the elements which make for the total vision? Might we describe these? I shall try a few thoughts.

I start with a personal realisation. I was reading Paradiso in the good English translation from which I quote here, preparing sessions for a group exploring the Divine Comedy, and feeling: “Well, alright, but this is difficult.” My vaguely searching eye saw that years before, when I had been studying it under an Italian tutor, I had written ‘Italian!’ against a verse in Canto XXX. So I read it aloud to myself:

O isplendor di Dio, per cu’io vidi

l’altro trïunfo del regno verace,

dammi virtù as dir com’ïo il vidi! (XXX, 97–99)

Dante's Paradiso, Canto XXX

NEVER MISS AN ARTICLE

Please follow and like us:

CATEGORIES

The music of the language suddenly excited me and I felt its beauty in the vibrations of the sound in ear, body and imagination. That gave a burst of inspiration for the teaching. I already knew the language was wonderful and carried the vision ever since I had been entranced by hearing that Italian tutor reading whole sections of the poem, but this was a further realisation. It prompted me to learn these lines and invite the group to speak them when we met. There are of course very good translations, but the intrinsic beauty of the original language is a primary reason why the Divine Comedy is so famous.

We can find other beauties in Paradiso. There are Dante’s famous images, as when the blessed souls fly into the heart of the Celestial Rose…

as a swarm of bees that in one instant plunge

deep into blossoms and, the very next, go back

to where their toil is turned to sweetness… (XXXI, 7 ff)

Dante's Paradiso, Canto XXX

As he nears the final vision, Dante fixes his eyes on the eternal Light:

In its depths I saw contained,

by love into a single volume bound,

the pages scattered through the universe. (XXXIII, 85–87)

This is the opposite of the Sibyl’s oracle which Dante has just mentioned, where the oracles are written on leaves and scatter in the wind. It is to me one of the deepest and most beautiful images of Paradiso because it holds everything – hell, purgatory and heaven – in a single volume, one story, a wholeness of vision and “the end of all desire.” (XXXIII, 46)

There are many more things one could point to – the beauty of thought, or spiritual enquiry, of certain characters we meet, of nature and human nature (not forgetting the dark side of these). But one vital final connection by which we recognise beauty must be discerned: beauty is always connected with love – is always both the cause and effect of love. Love is Dante’s theme throughout the Divine Comedy. Even in Inferno we are aware of its universal presence: when Dante and his guide, Virgil, see the fallen rocks as they pass the Minotaur, Virgil remembers the time this landslide occurred,

when the deep and foul abyss shook on every side

so that I thought the universe felt love. (Inferno, XII, 40–41)

He is referring to the earthquake at the time of the crucifixion and Christ’s descent into hell – there is no place where the divine love has not been.

Within Paradiso, love and beauty are threaded together with light. Dante is compelled by love to gaze on the beauty of Beatrice. (XXX, 13) The heaven of pure light is full of love. (XXX, 40) The love that calms this heaven prepares Dante for his next level of vision. (XXX, 52–54) He sees visages informed by heavenly love, resplendent with Another’s light. (XXXI, 49) It is love that, in the image mentioned above, binds the scattered pages. Love holds everything together.

And, finally, in the last stanzas of the poem, Dante’s vision of the beauty of the eternal Light itself surrenders into complete union with

the Love that moves the sun and all the other stars. (XXXIII, 145)

Email this page to a friend

Email this page to a friend

Image Sources

Banner: Monika Beisner, illustration to Canto 5.

Our thanks to Monika Beisner for giving permission to use images of her paintings for this article, and to Julia Hartley for reading Canto XXX.

Other Sources (click to view)

All references are to Canto numbers and lines in Paradiso and are from the translation by Robert Hollander and Jean Hollander, Anchor Books, 2007

The illustrations mentioned can be found in:

La Divina Commedia (The Divine Comedy) by Dante Alighieri. Inferno | Purgatorio | Paradiso: English edition in three volumes translated by Robert and Jean Hollander with 100 illustrations by Monika Beisner. Edizioni Valdonega, Verona, 2007.

William Blake’s Divine Comedy Illustrations. Dover Publications Inc., New York, 2008.

Paradiso: The Illuminations to Dante’s Divine Comedy by Giovanni Di Paolo by John Wyndham, Sir Pope-Hennessy. Random House, London, 1993.

Sandro Botticelli: The Drawings for Dante’s Divine Comedy by Schulz Altcappenber, Henry H Abrams, London, 2000.

Barbara Vellacott

With a background in adult education and overseas development issues, Barbara Vellacott now teaches poetry. She enjoys encouraging the reading of poetry – aloud wherever possible – as a form of personal and shared engagement with life, which is musical, emotional, intellectual and spiritual. Particular interests are William Blake and the English Romantic poets. In recent years the study of Ibn ʿArabī has also been a great inspiration. She lives just outside Oxford, UK.

NEVER MISS AN ARTICLE

If you enjoyed reading this article, please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

Please follow and like us:

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE:

Such great explanation. Some artists can’t handle the beauty of Paraiso

1