A Thing of Beauty _|_ Issue 10, 2018

A Thing of Beauty…

Emma Clark visits the Luohan at the Temple Gallery in London

A Thing of Beauty…

Emma Clark visits the Luohan at the Temple Gallery in London

Keats’ famous lines from the beginning of Endymion –

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness…

– give us the first clues to a definition of beauty: first, that it is timeless – “a joy for ever” – and second, that it is meaningful – “it will never pass into nothingness.”

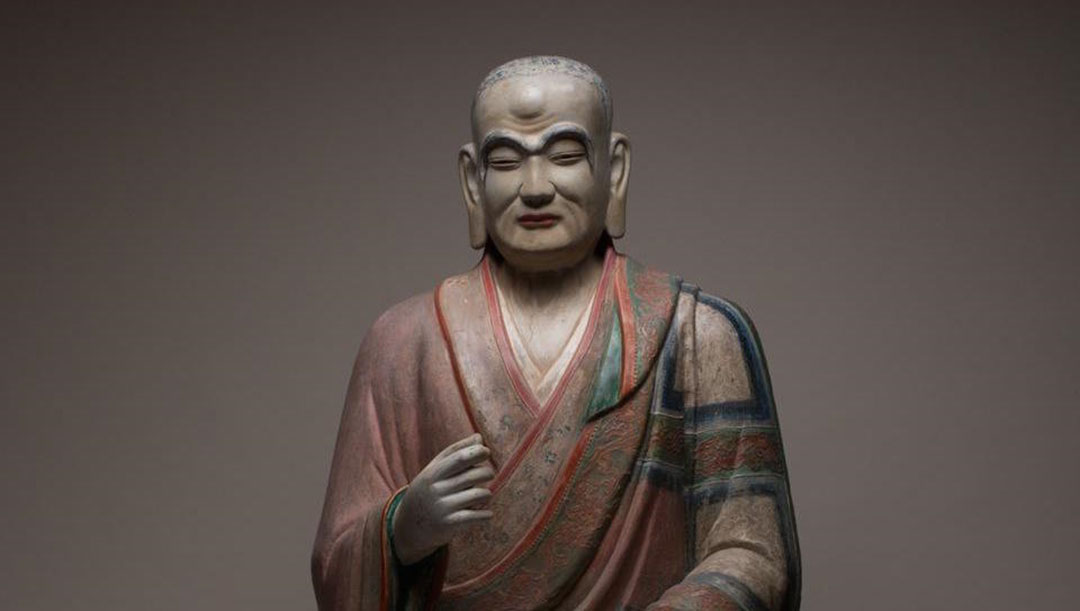

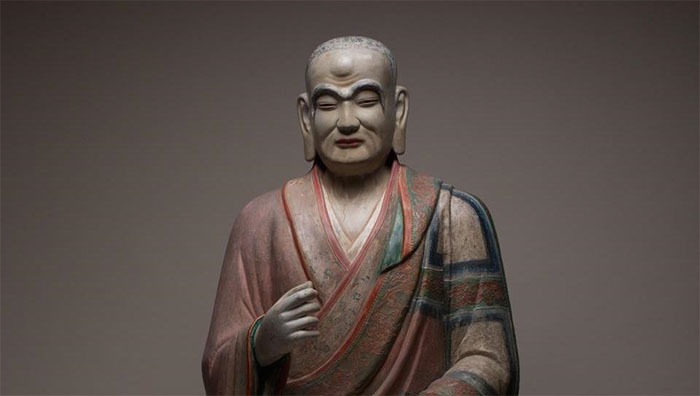

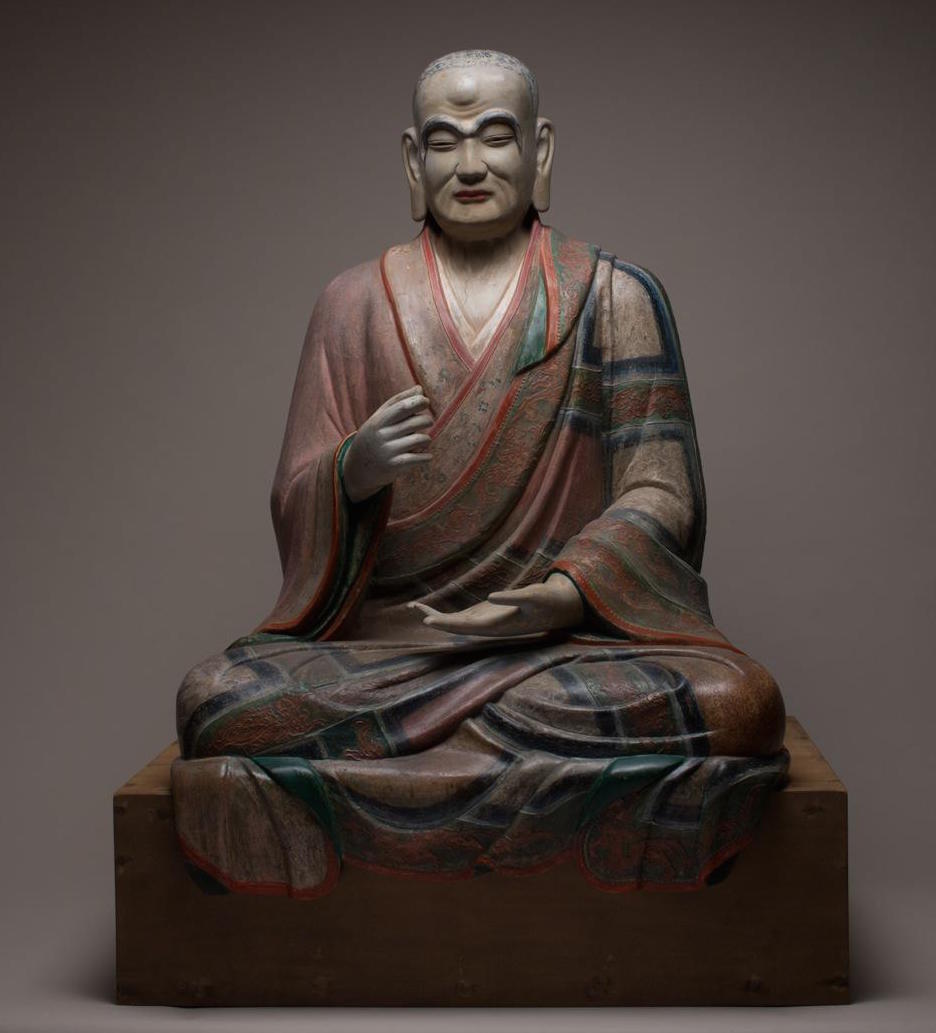

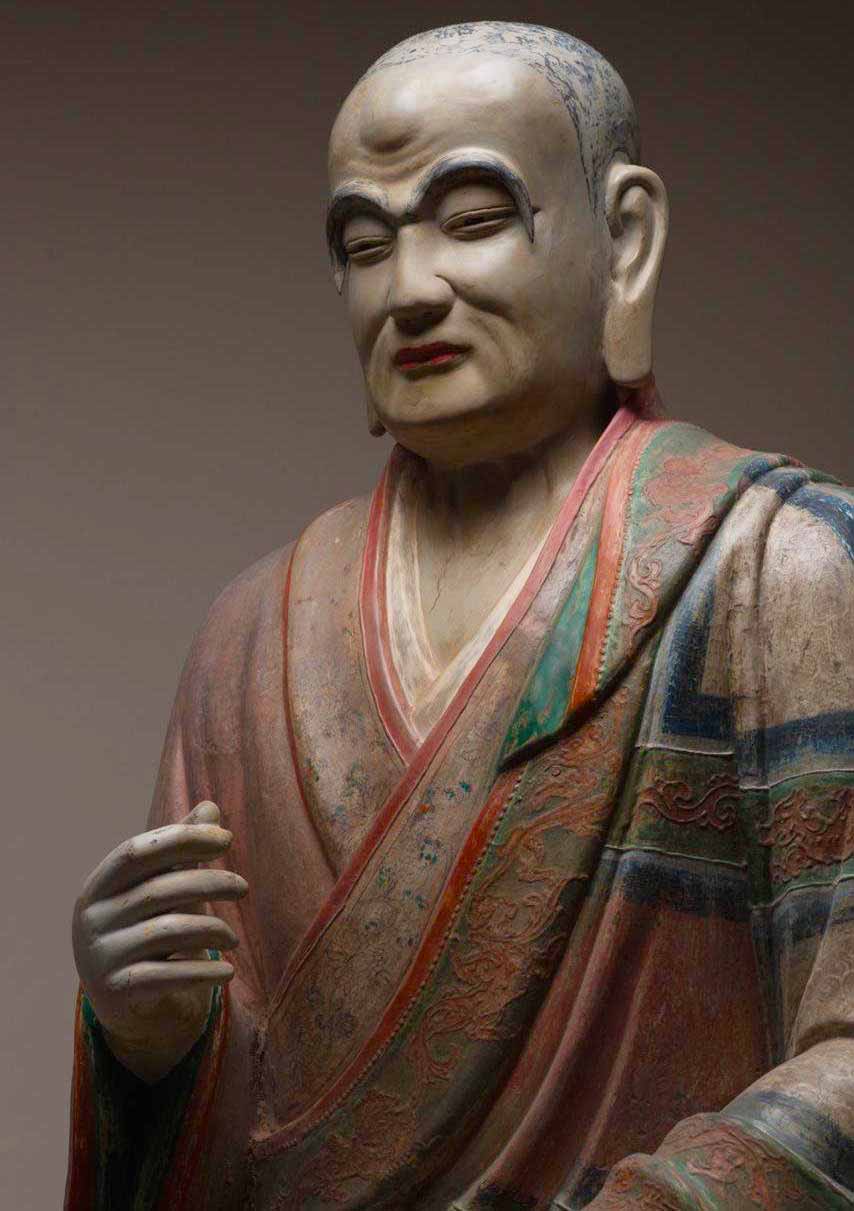

Armed with these criteria, I have chosen to write about the Luohan in the Temple Gallery in Holland Park. Luohan is the Chinese word (Sanskrit: arhat) for a Buddhist monk who has gained self-realisation through deep meditation and spiritual practice of the dharma, the Buddha’s teaching on the nature of Reality. The Luohan in the Temple Gallery is a late 14th-century (Yuan or Ming dynasty) Chinese sculpture in carved wood and gesso with some polychrome paintwork. He sits straight-backed, 117cm high, in the traditional lotus position of meditation, and is dressed in a flowing, coloured and patched robe, raised up on a wooden viewing platform.

The Luohan in Temple Gallery, London. Photograph: Temple Gallery

The Temple Gallery mainly specialises in icons, and the owner – Dr Richard Temple – welcomes visitors to view his exceptional collection. It is always a joy to do this, and the experience of spending time with such fine examples of sacred art gives one both visual nourishment for the eye and inward nourishment for the heart and soul. I always leave the gallery feeling supremely uplifted and with renewed inner strength. In addition to his icon collection, in 2012 Dr Temple acquired this Luohan, dark with age-old grime when discovered, unrecognised, in a lesser-known London auction-house. After careful cleaning by a conservator and some slight restoration (80% of the original colour remained) the saintly figure emerged in all its majesty and glory.

It is a representation of a “half-saint, half-Taoist adept, the mountain-dwelling hsien (benevolent spirits), their natures attuned to the workings of the Tao, who lived in isolation” (see Richard Temple’s own notes). It has been placed downstairs in the gallery in what has now become a kind of chapel. The visitor descends the narrow staircase from the main gallery and turns left into this small room – a sacred space for the sculpture – which becomes, after spending time in meditation before it, so much more than the word ‘sculpture’ suggests, so much more than what the visitor may at first observe with the outward eye. As one enters the quiet and peaceful sanctuary, this remarkable figure appears out of the dim light with a quite unexpected and astonishing presence, its beauty and grace taking one’s breath away.

The Luohan is definitely a ‘he’ and not an ‘it’, as there seems to be a living spirit or essence contained within the wood and gesso of the outward form. His eyes seem to be looking at you, the viewer, with a penetrating and ancient wisdom – which would be alarming except that at the same time there is enormous compassion and understanding. And after some time in his presence one experiences a kind of insight – albeit temporarily – a glimpse of one’s true self: one’s better self. Thus visiting the Luohan becomes a kind of pilgrimage where one is not only paying homage to a three-dimensional icon of beauty, wisdom and compassion, but one also receives, through the grace of this figure of incomparable calm, a taste of these divine qualities – and a reminder that we too may be able to grow spiritually. Titus Burckhardt in the remarkable chapter, ‘The Image of the Buddha’ in his book Sacred Art in East and West, writes that there is:

… something like a magical relationship between the worshipper and the icon: the icon penetrates the bodily consciousness of the human, and the human as it were projects him or herself into the image; having found within that of which the image is an expression. (p.131)

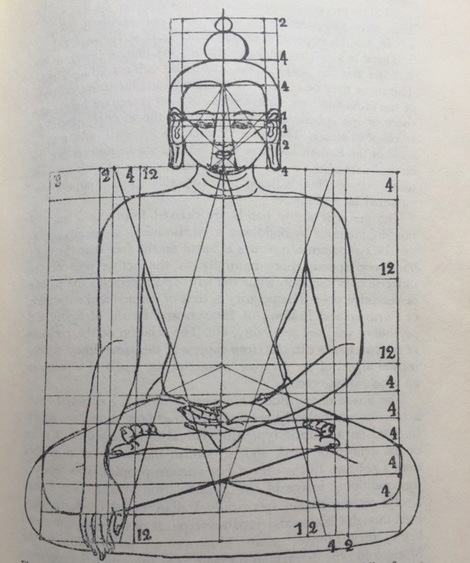

Diagram of the ‘true image’ of the Buddha, drawn by a Tibetan artist. From Titus Burckhardt: Sacred Art in East and West

Spirit and Form

Everything about the Luohan’s material form is proportionally correct and in harmony. This is essential (along with other criteria below) in order to attract the eternal spirit to ‘dwell’ within the outward temporary material sculpture. The Luohan is similar to traditional representations of the Buddha, where measurements are proportionally reduced from the larger square of the seated body – including the lotus-positioned legs but not including the head – to the smaller square of the head. Titus Burckhardt explains that the measurements are “founded partly on a canon of proportions and partly on a description of the distinguishing marks of the body of a Buddha derived from the Scriptures”. He goes on:

Another story is that a disciple of the tathagata (the Enlightened One) tried in vain to draw his portrait; he could not manage to seize the right proportions, every measurement turning out to be too small; in the end the Buddha commanded him to trace the outline of his shadow projected onto the ground. The important point is that the sacred image appears as a ‘projection’ of tathagata. (p.126)

The gestures of the hands are the mudras inherited by Buddhism from Hinduism. The right hand, raised up in this Luohan, symbolises the active pole, while the left hand, in open and accepting position, is the passive pole. These specific gestures, along with the prescribed proportions – handed down via tradition and the age-old method of transferring knowledge and skill from master to apprentice – make certain the ‘true image’ of the Buddha. They “ensure the static perfection of the figure as a whole, and an impression of unshakable and serene equilibrium” (Burckhardt).

Luohan detail. Photograph: Temple Gallery

However, there is a certain human individuality in our statue which is not present in the more abstract perfection, the “symmetry and static plenitude” of a statue of the Buddha. Indeed, reading the fascinating research on the Temple Gallery website, it seems that the master-craftsmen of this period emphasised the individuality of their Luohans, making them less distant and more attractive to the viewer/worshipper. As if to accentuate the humanity of our sculpture, opposite him in the ‘chapel’ is placed a stone head of a Buddha, which emanates a radiant and silent beauty; but it is definitely more distant than the Luohan, whose compassion and love are perhaps more evident to the human eye and soul.

Burckhardt makes an analogy between the image of the Buddha and the stupa (shrine containing a relic), and this may help us in our understanding of the profundity of this Luohan since – as with Christ and the Cathedral, Purusha (the cosmic human) and the Hindu Temple – the stupa may, according to him, “be considered as representing the universal body of the tathagata”, the various levels in a stupa representing the different planes of existence. The Luohan echoes this relationship, not only between the Buddha and the stupa but also between the individual and the universal, the microcosm and the macrocosm. Thus one may see our figure as an image of what the Christian and Islamic traditions refer to as the ‘universal human being’, and through identifying oneself with the essential proportions expressed through the traditional form, the individual may, as Robert Lawlor writes “contemplate the link between his own physiology and universal cosmology”.

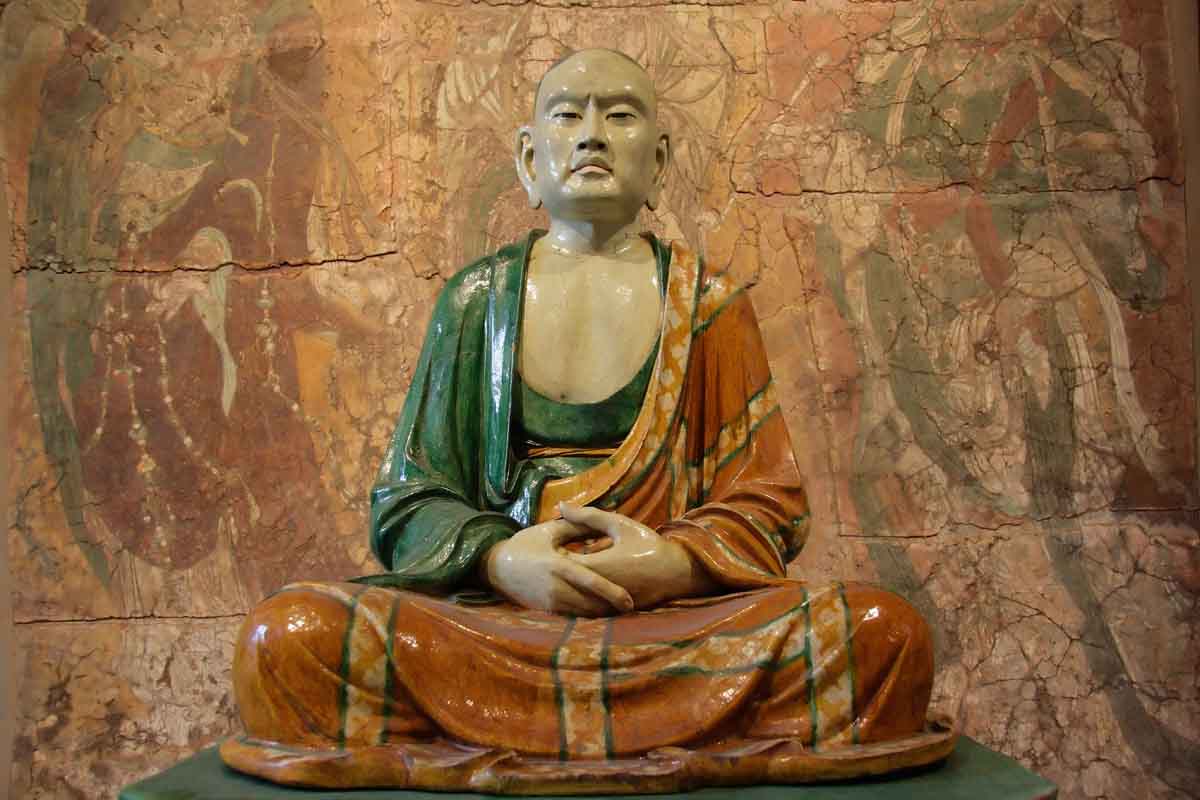

The Luohan in the British Museum, Liao Dynasty, stoneware ceramic. Photograph: Jon Bower London / Alamy Stock Photo

The Making of a Luohan

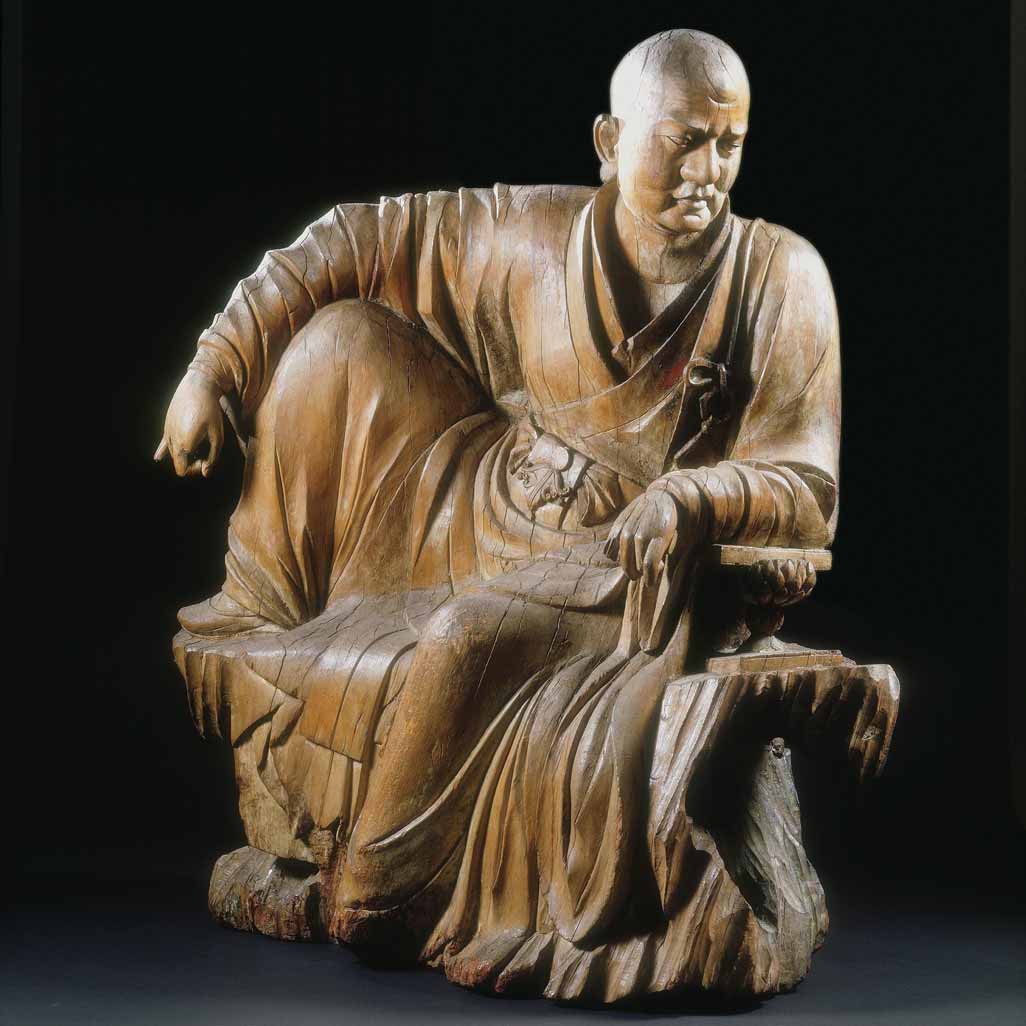

According to the Temple Gallery’s research, Luohans are much more rare than Buddhas and Bodhisattvas of this period. There are two in London that ours may be compared to: one of coloured glazed pottery in the British Museum and one in the Victoria and Albert Museum. But neither are as compelling. Sculptors and painters created their Luohans in such a manner that they were seen as “dignified, ordinary, though idealised monks”. Indeed, although great and majestic, our Luohan is also very loveable, like a saint.

And as with other Luohans, the supernatural aspects and highly developed spiritual powers are emphasised by exaggerated features such as the very strong arched eyebrows, one eye slightly more closed than the other, the large-lobed ears and the protuberance on the forehead – “as if the body had paid the price for his intense efforts to become enlightened”.

The Luohan in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Photograph: Courtesy of the V&A

These outward characteristics and the manner in which they have been created by dedicated, highly skilled and knowledgeable craftsmen over years of practice, together with long experience working with traditional methods and materials (lime wood in this case), not to mention their internal wisdom, are all fundamental in the creation of such a beautiful example of sacred art. If one criterion of sacred art means to open up the heart and soul towards the eternal peace that lies deep within all of us, then the Luohan is indeed a powerful example. It is a demonstration of the full integration of the head, heart and hands by the master-craftsmen who made it, whose outward skill was matched by an inner purity of soul. These qualities are vital to the master-craftsman when engaged in the process of making his work of art, because without them the spirit of the Luohan would not be attracted, as mentioned earlier, to ‘dwell’ within the form he creates.

In fact, when contemplating the Luohan for any length of time, it is almost as if one were participating, along with the craftsman, in the process of creating it. The experience is a beautiful illustration of Plato’s distinction between the outer and inner eye, since we are not simply looking at him with our outer pair of eyes but rather, crucially, his beauty and stillness re-open the ‘eye of the soul’, or as Plato says “causes a new fire to burn” there; and this inner eye “is more important than ten thousand eyes since it is by it alone that we contemplate truth”.

The restoration of the shoulder. Photograph: Richard Temple

The Timelessness of Beauty

To return to the beginning of this essay and our criteria: without question this majestic and profound sculpture is both timeless, speaking to us more powerfully than ever in the 21st century – over six centuries after it was created – and deeply meaningful in its capacity to help us to know ourselves and to give us an insight into what it means to be human.

Finally, the Luohan’s profound manifestation of beauty, grace and compassion may be a powerful comfort in our hours of need as well as helping us to surpass our lower selves on our journey towards finding our still and peaceful centre. Today, more than ever, we need every vehicle of grace available to help us regain the divine unity that lies within each and every one of us. Our Luohan helps us to recollect that true beauty is a reflection of truth, and that love and compassion in humankind is always a reflection of divine love.

The last word on beauty goes to Frithjof Schuon who writes in his chapter on Buddhist Art:

Beauty is like the sun: it acts without detours, without dialectical intermediaries, its ways are free, direct, incalculable; like love, to which it is closely connected, it can heal, unloose, appease, unite, or deliver through its simple radiance. (p.94)

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner picture: Detail from the Luohan in the Temple Gallery, London. Photograph: Temple Gallery.

Other Sources (click to open)

TITUS BURCKHARDT: Sacred Art in East and West, Its Principles and Methods, Perennial Books 1986.

ROBERT LAWLOR: Sacred Geometry: Philosophy and Practice, Thames and Hudson 1989.

PLATO: Republic, VII. 527, quoted in Robert Lawlor: Sacred Geometry.

FRITHJOF SCHUON: Art from the Sacred to the Profane: East and West (Writings of Frithjof Schuon, 1907–1998), World Wisdom 2007.

Emma Clark teaches on the Masters Programme at The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts [/] in London where she focuses on teaching the universal and timeless principles of sacred and traditional art. She is also a garden designer specialising in Islamic gardens and gardens of other sacred traditions. She has published two books on Islamic gardens: The Art of the Islamic Garden (new edition 2010), and a monograph, ‘Underneath Which Rivers Flow’, The Symbolism of the Islamic Garden, (1996) as well as many articles on Islamic art and architecture, sacred and traditional art in general. Emma is a member of the Academic Board of the Temenos Academy [/] and is Registrar of the Temenos Academy’s Foundation Course in the Perennial Philosophy [/]

Email this page to a friend

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Choje Akong Tulku Rinpoche

Vin Harris talks about the life of a remarkable man

d-r-a-w-n-i-n-w-a-r-d

Nicola Simpson on Dom Sylvester Houédard

Yoga: a spiritual practice for our time

An interview with Judith Hanson Lasater

A Thing of Beauty…

Frank Lloyd Wrights’s masterpiece Fallingwater

READERS’ COMMENTS

Beauty : Being Beholding Believing

How very remarkable and,to me, prescious reveal of the meaning of this beautiful sculpture. Thanks so very much.

Beautifully written and truly inspiring. I hope to stand before the Luohan at the Temple Gallery one day soon. Sincere thanks.

1