Well-Being & Ecology _|_ Issue 20, 2022

Fighting Fire with Fire

Victor Steffensen talks to Rosemary Rule about his pioneering work reintroducing indigenous cultural burning practices in Australia

Fighting Fire with Fire

Victor Steffensen talks to Rosemary Rule about his pioneering work reintroducing indigenous burning practices in Australia

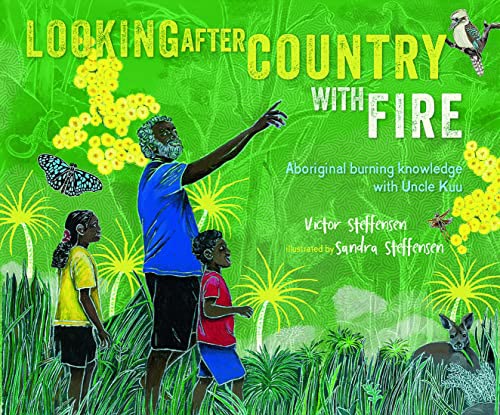

One of the most visible effects of the climate crisis has been the sight of wildfires raging in the great forests of America, Canada, Australia and Europe. As the devastating consequences of global warming become clear, there is increasing interest in the wisdom of indigenous traditions which for millennia cared for the environment in a sustainable way. In this article we talk to traditional fire practitioner Victor Steffensen [/], who has pioneered the reintroduction of aboriginal burning methods in Australia. A filmmaker, musician, and educator, Victor is the co-founder of the National Indigenous Fire Workshops and the Firesticks Alliance, and the author of two books which lay out the benefits of this ancient practice: Fire Country [1] and a bright and accessible picture-book, Looking After Country with Fire, for younger people. We spoke to him by phone from his home near Cairns in Far North Queensland.

During the summer of 2019–20 Australia was hit hard by a series of raging bushfires. It was the most catastrophic season ever experienced in the country’s history. Thirty one million hectares, primarily forest and bushland, were lost along with 33 lives and over 3,000 homes. One-fifth of Australia’s forests were lost and an estimated 1.25 billion animals killed, the impact of which will be felt for years to come.

During the summer of 2019–20 Australia was hit hard by a series of raging bushfires. It was the most catastrophic season ever experienced in the country’s history. Thirty one million hectares, primarily forest and bushland, were lost along with 33 lives and over 3,000 homes. One-fifth of Australia’s forests were lost and an estimated 1.25 billion animals killed, the impact of which will be felt for years to come.

The Australian climate is generally hot, dry and prone to drought, so some parts of the country have always been vulnerable to bushfires, also referred to as wildfires, which historically – or at least since the arrival of European settlers in the 18th century – have been an intrinsic part of the environment. But the extent and intensity of the 2019 fires has been widely seen as a direct effect of climate change and global warming, prompting debate between fire management authorities, farmers and bureaucrats about causes, mitigation and strategies. There is an urgent requirement to manage the land to minimise, if not prevent, wide-scale and devastating fires in the future.

One positive response to the catastrophe is that many more people are referencing and implementing traditional knowledge practices. These constitute the wisdom of the First Australians, who have lived and managed the land continuously for over 60,000 years. Where they have been re-introduced, Aboriginal fire practices have been shown to not only enable the country to avoid mega fires, but also to effectively improve the health of the land, keeping the ground and waters clean so that the natural resources flourish.

An articulate and passionate man, Victor Steffensen has been at the forefront of this movement, re-engaging traditional practices through creative community projects, and promoting the need for Aboriginal voices and knowledge to be heard. He believes that “Aboriginal cultural burning is not just about controlling fire; it is about looking after the land better and understanding the ancient values of indigenous cultures world-wide.” A filmmaker, musician, author and educator, Victor’s approach is based on a holistic knowledge map which includes people, the relationship with the land, and our evolving culture.

Discovering Cultural Burning

Victor is a descendant of the Tagalaka people from the Gulf Country of North Queensland on his mother’s side. However his grandmother was one of the many indigenous children who were taken away from their families off Country for ‘re-education’. She worked as a maid in Kuranda, north-west of Cairns, and Victor grew up there in an Aboriginal community. Then, as a young man in the 1990s, when living in Laura in the far north of Queensland, Victor met up with two culturally respected senior Aboriginal men, George Musgrave and Tommy George (Poppy and TG) of the Kuku-Thaypan people.

Victor is a descendant of the Tagalaka people from the Gulf Country of North Queensland on his mother’s side. However his grandmother was one of the many indigenous children who were taken away from their families off Country for ‘re-education’. She worked as a maid in Kuranda, north-west of Cairns, and Victor grew up there in an Aboriginal community. Then, as a young man in the 1990s, when living in Laura in the far north of Queensland, Victor met up with two culturally respected senior Aboriginal men, George Musgrave and Tommy George (Poppy and TG) of the Kuku-Thaypan people.

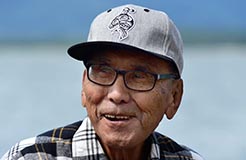

Already in their sixties and seventies, they were the last of their tribe to hold its ancient knowledge, and also the last speakers of the Awu-Laya language. They transmitted what they knew to Victor, teaching him how to “burn the country in the old traditional way to improve the land”.

The philosophy behind indigenous burns is in direct contrast with most Western fire regimes that are based on hazard reduction or back burning. What makes it different, Victor explains, is that the Aboriginal people aim for a ‘cool burn’ which does not reach as high as the canopy of the forest, giving time for wildlife to move out. “We set the right fire in the right ecosystem, so that we enhance the native vegetation. We apply fire in the way which is best for the country.”

Determining the ‘right fire’ requires an intimate knowledge of the environment, and careful observation. Traditionally, when the fire season was about to start, the Elders would put in their first burns based on relational indicators as to what vegetation was ready to burn, when animals were breeding, which plants were fruiting – ‘reading the land’. “If the grass feels cold, there is too much moisture; if it feels warm and dry, it is ready to burn. You look for the right ignition point and light up respectfully, not putting too much fire in – just enough to let it burn. Burning too late in the season with too much heat won’t get the best regrowth response and the trees will get burnt, the country will end up pretty bare throughout the year.”

The Elders taught Victor that there is a narrow window of time to produce the right fire: to apply the right heat for the soils so that the fire burns cool and in a circle, and does not destroy the trees or the canopies.

When Victor first met Poppy and TG, the Aboriginal people had no role at all in official land management. Even after the return of lands to them with the Land Act of 1976, their areas were designated as national parks and they were not allowed to start fires. Nevertheless, in the 1990s, Poppy, TG and Victor embarked, without official permits, upon a programme of traditional burning to heal the damage to the land which the elders had long observed.

This initially provoked strong opposition from local landowners and government rangers, but within two or three years, the benefits in terms of regeneration and cleansing had started to become obvious. Coupled with Victor’s efforts to explain what they were doing at a series of talks and workshops, this sparked a revival of interest in the practice which has now become nationwide. Indigenous cultural burning practices are being introduced more frequently, and effectively, in Queensland, but also further afield in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. Many communities are engaging in workshops and forums led by local Indigenous fire managers, who are working alongside government fire services.

Dr George Musgrave and Dr Tommy George holding a fire torch. Photograph: Victor Steffensen

Capturing The Knowledge

.

A major factor in communicating the wisdom of traditional practice was Victor’s innovative use of a video camera to record the teachings of Poppy and TG. “Translating, educating and recording indigenous and community knowledge is best done through visual storytelling” he explains. “I believe that film is the closest way that technology can match traditional transfer and the passing down of knowledge. My dream in portraying these stories is to encourage and continue the oral teaching practice of indigenous peoples which sustained cultures worldwide over thousands of years.”

A further breakthrough came in 2004, when a postgraduate student, Peta Standley, visited the Kuku-Thaypan area and set up a research project to assess the effects of the burning in scientific terms. As part of her research, she persuaded the James Cooke University in Townsville, near Cairns, to acknowledge the value of Poppy and TG’s contribution by awarding them honorary doctorates. This collaboration with contemporary science led not only to validation of the traditional ways of land management, but also to an increasing appreciation of the depth and complexity of indigenous knowledge. Victor refers to his mentors as ‘walking encyclopedias’ and begs people to just listen to what the Aboriginal people have to say. “There is a knowledge system, an intelligence there – all the information needed for looking after the environment.”

He adds: “The healing of Country is crucial. Indigenous cultures have been practicing sustainability for thousands of years and we have to learn from the experience of what humanity has already achieved. Unfortunately so much of it has now been destroyed but we can still learn to read the landscape and look after it. Through that we will find ways to improve areas of agriculture, education, the economy and even improve technology in certain ways.”

Since 2008, the knowledge gained in Cape York has been extended through the work of the National Indigenous Fire Workshops and the Firesticks Alliance [/], of which Victor is a co-founder. They organise annual on-country workshops in various Queensland communities in order to develop the knowledge of cultural burning for different landscapes. Since 2018, these have extended into other parts of the continent, where they have managed to show how the traditional knowledge practices can be successfully applied to a wide variety of ecosystems.

Victor at a Firesticks workshop with school children. Photograph: Youtube [/]

The Wider Picture

.

There is also interest beyond Australia, and Victor has recently travelled across the world to assist with setting up fire programmes in other places where mega fires have swept through the country. This has involved making connections with other First Nation people – such as the Sami people of Scandinavia, and communities in California and Canada.

His work in Australia has also moved in other directions. “Fire is just the beginning. Nowadays I find myself undertaking projects in health, culture, agriculture, education and environment. By working with communities and documenting their aspirations via the art of film, I began to see the possibility of empowerment which has the potential to pave a road for generations to follow.”

To this end, he has established The Living Knowledge Place [/], a community-driven education site that showcases indigenous culture and the aspirations of indigenous people for the future of the environment and human well-being. “What I see missing in Australia today is the opportunity to demonstrate our values, and the benefits of them if they were shared by mainstream society. I have learned over the years that the best way to have influence, or make a difference, is by having fun, re-implementing activities we believe in, and creating education for our children. The common desire I find in elders right across Australia and the world is to have indigenous knowledge taught in schools.”

California: Crews use drip torches to ignite prescribed burns during the 2020 Klamath Prescribe Fire Training and Exchange Program (TREX). Native American tribes in California are now being given permission to practice cultural burning in order to prevent the wildfires. Photograph: Stormy Staats/Karuk Tribe

Asked about applying Aboriginal knowledge to global environment-related problems, he comments that too much focus is still put on artificial intelligence rather than on natural intelligence. “In relation to wildfires, we are still approaching the problem in the same old way – with technology. It seems that many people just don’t understand the knowledge values that come from our ancient cultures, and this absence has created a majority of humans who are unconnected to the natural world we live in. They still don’t get it, even after the worst wildfires we have ever seen are threatening many parts of the world.”

In his book Fire Country, Victor explains that ‘climate change’ has two meanings. There is the natural change which is part of our ongoing life on earth and to which, over thousands of years, human beings have been adapting. And there is the man-made change to which the harmful traits of human action are continuing to contribute. “We need to be adaptive in finding ways to combat the human-induced endeavors that are so focused on producing fossil fuels – the land clearing and deforestation and the effects that this is having, such as mass extinction of flora and climate change around the globe. We have to start being practical and learn to treat our natural resources and ourselves more respectfully.”

Acknowledging that we are now facing the biggest environmental challenges in modern history, Victor firmly believes that we need to start dealing with the issues right now. “Whatever the concerns and views, we need to get away from the debates and just get on with doing something. Climate change means the land is telling us something. It is not all doom and gloom. If we look at it the right way, it is an opportunity for change, but we must all come together to realise it.”

An important part of this effort is that the holders of traditional knowledge and the practitioners of modern science work together. As Victor puts it: “Pulling together to create the new wave of a human environmental evolution, hopefully we will escalate to the next level of intelligence.”

To learn more about Victor and his work, see this video which tells the story in more detail:

Video: How Indigenous fire management practices could protect bushland – Australian Story. Duration 26:52

During the wildfires of 2020, a song came to Victor. So he banded together with six independent musicians – Merindi Schrieber, Nikki Doll, Aiden Brim, Torres Webb, Patty Preece, and Victor’s partner Natalia Mann – to record it. Mulong is his traditional name:

Video: ‘Great Land’ by Mulong. Duration: 4:30

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Victor Steffensen. Photograph: Brian Lister, courtesy of Victor Steffensen.

Inset: Tree fern in Bluemountain National Park, Australia. Australia has 134 million hectares of forest– 17% of its landmass. Photograph: Eduardo Cabanas / iStock.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] VICTOR STEFFENSEN, Fire Country (Hardie Grant, 2020).

[1] VICTOR STEFFENSEN, Fire Country (Hardie Grant, 2020).

[2] VICTOR STEFFENSEN (author) & SANDRA STEFFENSEN (illustrator), Looking After Country with Fire: Aboriginal Burning Knowledge with Uncle Kuu (Hardie Grant Explorer, 2022).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Introducing: Firestacks: Time, Tide and Gravity

Fiona Bisset presents a video about Julie Brook’s remarkable installation in the Outer Hebrides

Redescovering Our Earth Emotions

Environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht talks about climate change, solastalgia and his inspiring vision for the future

Paddling the Magic Canoe: The Wisdom of Wa’xaid

Briony Penn talks about her relationship with the native elder Cecil Paul – Wa’xaid – and their successful campaign to preserve the glorious Kitlope River area in British Columbia

The Unity of Bee-ing

An interview with Heidi Herrmann about the work of The Natural Beekeeping Trust in preserving our precious population of bees

READERS’ COMMENTS

Well presented and really useful information and a hopeful message after the disastrous fires of recent years. And the videos are definitely a must-watch.