Well-Being & Ecology _|_ Issue 19, 2021

Rediscovering Our Earth Emotions

Environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht talks about climate change, solastalgia and his vision for the future

Rediscovering Our Earth Emotions

Environmental philosopher Glenn Albrecht talks about climate change, solastalgia and his inspiring vision for the future

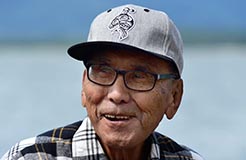

Glenn Albrecht is a philosopher and environmentalist who for many years was Professor of Sustainability at Murdoch University in Western Australia, and is now an Honorary Associate at the School of Geosciences at the University of Sydney. In his book Earth Emotions: New Words for a New World (2019) [1] he argues that we have lost awareness of our deep and long-lasting connection with nature, and no longer have words to express the distress and grief we feel as climate change and development destroys the world that we once took for granted. He has coined new words for these ‘earth emotions’ – solastalgia, ghedeist, soliphilia – which are becoming widely used. In this interview, he talks to Jane Clark and Jim Griffin from his home on Wallaby Farm in New South Wales about his own experience and his vision of how, even at this late stage, we might reconnect with nature and enter into an inspiring and creative future.

Jane: As I understand it, the essential message of your book Earth Emotions is that there’s a connection between the state of the earth and our own mental and emotional states. We’re deeply embedded in our relationship to nature and have both positive and negative emotions associated with it. But in western languages, at least, we don’t really have words for them. So you have set out to create them. The best known, I think, is the term ‘solastalgia’. Can you start by saying something about this?

Jane: As I understand it, the essential message of your book Earth Emotions is that there’s a connection between the state of the earth and our own mental and emotional states. We’re deeply embedded in our relationship to nature and have both positive and negative emotions associated with it. But in western languages, at least, we don’t really have words for them. So you have set out to create them. The best known, I think, is the term ‘solastalgia’. Can you start by saying something about this?

Glenn: Sure. Solastalgia is really the result of what I call my ‘sumbiography’, which is a term I use for the cumulative influences on my life from my relationships with both human beings and non-human nature. I was fortunate to grow up in Perth, in Western Australia, the most isolated capital city in the world, which is also one of the global hot spots for biodiversity, famous for the uniqueness of its plants and animals. I grew up with a deep appreciation of nature, largely due to my grandparents and my mother, who were able to nurture a love of life and of the beauty of nature around me. So I took it for granted that these positive, amazing experiences that I had as a child were universal.

And yet, as I grew up, Western Australia began to develop in ways that were typical of the rest of the world. Our big forests were being converted into woodchips, and development was taking nature further and further away from the city; you could still get there, but it would take half a day, and then a day. And so I was made aware, even as a child and then as a teenager, that the world was transforming extremely rapidly.

I was intent on becoming an ornithologist, but various things in my life put me on track towards a more philosophical, psychological, sociological way of looking at the world. So I started a PhD in philosophy at the University of Western Australia. That was going okay until my supervisor had a heart attack and had to retire, which meant that I had to find a new supervisor to help me through a thesis on organicism and Hegel. There weren’t many people who could cope with that, so I ended up going east with my family to Newcastle in New South Wales. That put me into a whole new space in terms of the environment. The place where I ended up living was in the Hunter Area. It is a beautiful subtropical region, also very rich in biodiversity.

Jane: So that it where you first encountered the effects of industrial development?

Glenn: I’ve always been in love with birds, and one of the things I wanted to do when I got to New South Wales was to explore the areas that John Gould and his wife, Elizabeth, had explored in 1839–40 for their famous book Birds of Australia.[3] But this meant also passing through areas of Hunter Valley which are now converted to coal mining; in fact, this region is now the world’s leading black coal exporter. I was reading about what the region was like in 1839, and at the same time I found myself travelling through the contemporary area which is 500 square kilometres of open cut or opencast mining with massive power stations and railway lines which convey the coal. When I first saw this, a huge, transformative emotional wave just washed over me and I experienced a feeling of disaster, of distress and deep unease. And that was when I realised that I didn’t have a word to describe my own emotional state. Distress is a word that’s used in a multitude of human experiences, but I wanted a word that related to the distress specific to environmental desolation. And it wasn’t there.

The Age of Solastalgia

.

Jane: Your starting point I think was the concept of ‘nostalgia’.

Glenn: Yes. The closest I could find was ‘nostalgia’ as defined by Johannes Hofer, the Swiss physician in the 17th century. Nostalgia as classically defined is the deeply melancholic feeling that people have when they are absent from their home and wish to return. It’s a kind of homesickness and it can be alleviated by being repatriated, by going back to the fatherland or the homeland. But the people living in Hunter Valley, who are still attempting to farm and have a normal life surrounded by these gargantuan coal mines, were having their lives turned into a misery without leaving their homes. The term ‘solastalgia’ includes the idea of solace – the solace that you feel in your home environment. And ‘algia’ is pain, distress and sorrow. So it means the distress you experience when your home is destroyed while you are still living there.

And the idea has grown from there. There is a journal called PAN (Philosophy, Activism, Nature) that was prepared to accept what was initially a short essay designed to stimulate discussion and help turn it into a more thoughtful and considered article.[3] The period from 2005 to now has seen – unfortunately, really – solastalgia being widely accepted as a term by all sorts of people. It is actually only the first of what I call ‘psychoterratic’ (psyche-earth) concepts [/]. I am devoted to the task of fully explicating all of the positive and negative earth emotions that we have, because even though we may have had them in the past, we seem to have lost these sensibilities in the last two or three hundred years since the Industrial Revolution.

Jim: You relate solastalgia to the way that indigenous people – for example, the Aboriginal people of Australia – have felt the loss of their homeland, and point out that this is not a minor thing: people cannot function; they suffer from memory loss and cognitive decline; many of them have taken refuge in alcohol and such like in order to deal with the depths of despair that they feel.

Glenn: The traditional people of Australia have undergone a double-whammy of psychic blows. Colonisation has also been a form of deep and immensely distressing nostalgia because of the loss of both their culture and place. Their culture is 60,000 plus years old, so it is not something that can be dismissed with a wave of the hand and an injunction to get into the 21st century and enjoy Netflix. And of course, they are still living in Australia and Tasmania, where climate change, global scale development and multinational mining is destroying what’s left of the homeland that is their spiritual, physical and material base.

Jim: You use the expression ‘lived experience’, and it seems to me that one of the great strengths of your writing is not just the creation of words that allow us to focus more on what we’re feeling; there is also the storytelling, the lived experience that you bring into telling the tale.

Glenn: Indeed. This has been a very important part of my work as a philosopher, and I have collaborated with people like Linda Connor, an anthropologist, and my close friend, Nick Higginbotham, who’s a social psychologist. When I first started to think about these things, I knew that I could not be the only person experiencing this kind of distress. So together we went out and interviewed people about what they were going through in the Hunter Valley, and gathered hundreds of testimonies from people about their lived experience.

But I’ve always seen this matter as a world issue. Under the impact of climate change and globalised development forces, I believe that we now live in the age of solastalgia [/]. It’s no longer an isolated experience of people in particular parts of the world, but we’re all now feeling the effects of ecological change and loss of our environment globally – although it’s maybe only at the mild end of the spectrum for most of us at the moment. People from the social sciences, the humanities, philosophy, artists and other creative people are now using the term to explain the distress that we’re all experiencing at the loss of the solace, the beauty, the coherence and the integrity, of the world that we once took for granted.

The rare black-footed rock wallaby, which is being reintroduced to Western Australia with the help of the Martu people. Photograph: Nature Picture Library [/] / Alamy Stock Photo

The Problem of Mental Health

.

Jane: In the UK, we’re talking about mental health problems now as an epidemic. It’s coming to the top of the of the agenda, especially in regard to young people, where there has been a huge rise in depression, anxiety, etc. My own feeling is that this is very much to do with what you’re talking about. But these states are being treated as medical conditions and consequently personalised; the solution is seen as giving individual people counselling or therapy. You mention that this is also a danger with solastalgia: that it could be seen as a medical problem that can be ‘cured’.

Glenn: Actually, solastalgia has not been interpreted in this way. Most people have understood that it refers to the dimension of existential lived experience, not just a condition of the biomedical brain. It’s a condition of the soul – of our spirit, of our psychological and emotional coherence.

But in general, as a philosopher and sociologist, I absolutely agree with what you say, I’ve always taken the view that there’s more to these global mental health issues than psychiatric and neurological distress. Basically, we’re making ourselves crazy by destroying the very foundations on which we live, and yet people think that they can cure the problem with therapy!

Jim: What you are saying takes me back to the work done in the 1960s and the radical psychiatry movement. Their point was that mental illness is in some ways a rational response to an insane world.

Glenn: I grew up reading R.D. Laing and Thomas Szasz and others who were critiquing the biomedical view of mental illness. Gregory Bateson was, and remains, a tremendous influence; back in the 1970s he could see the connection between the destruction of our biophysical environment and the destruction of our own mental sanity – our own capacity for strength and health in our psychological world. It should be no surprise, really, that these two are intimately related. During the 3.5 billion years of evolution it has taken to produce humans, there has been a deep and meaningful connection to the rest of life. It’s only in the last two or three hundred years that we have discarded that.

Jane: So you would agree with the motto of The Radical Therapist [/]: ‘Therapy means social, political and personal change, not adjustment’?

Glenn: Yes; in fact, in my very first article on solastalgia,[2] I wrote about the fact that indigenous Australians found relief from solastalgia by being actively engaged in repairing their damaged communities – their damaged ecosystem – by doing things like getting rid of feral animals and replacing them with native species (see video right or below for more one of these projects involving Martu rangers in Western Australia.) If the cause of your distress is the destruction of your environment, it’s not your personal problem; it’s external and the solution is political, economic and a whole lot of other structural things.

Video: The Black-Flanked Wallaby. Duration: 2:04

So it’s important to get the structural issues that are causing our problems into the spotlight. If we can share the experience of bringing about changes to them, that is in itself a form of rehabilitation. It’s a form of repair of our own psyches at the same time as repairing the material base from which we spring, whether it’s our community or our rainforests. Internally and externally, it’s the same structure.

The lace monitor or tree goanna (Varanus varius), a member of the monitor lizard family native to Eastern Australia. It can reach 2 metres (6.6 ft) in total length and 14 kilograms (31 lb) in weight. Photograph: Glenn Albrecht

Interconnectedness and ghedeist

.

Jane: Solastalgia is a word for negative emotions about our relationship to the environment, but you also talk about positive emotions. For instance, you have coined the word ghedeist to embody the spiritual aspect of our relationship to the world, our sense of deep interconnectedness with all living beings.

Glenn: This comes from the Indo-European word ghehd, which means to unite, and is connected to words like ‘good’ or ‘together’ or ‘to gather’. And geist is a German word which means ‘spirit’ or, you know, something which is connected to the non-material, the élan vital [/] or whatever word you wish to use; it refers to the spiritual energy. So I put the two together to try and talk about a secular spirituality that comes closer to what I feel when I’m on Wallaby Farm bird watching or looking into the eyes of a poisonous snake. This is something that I think all of us have the potential to feel, largely because we’re products of evolution in both a Darwinian and Margulisian sense – I am referring to Lynn Margulis [/] who formulated the symbiogenesis version of evolution. I put the idea of ghedeist out there to stimulate further thinking about what it means to be a spiritual person in a material world. I am not a religious person in any conventional sense of the word, but I would say I am a spiritual person and I believe that there are lots of other people like me.

Jane: Lynn Margulis is very much associated with the concept of Gaia, which is a way of seeing the world as an interconnected whole. But ghedeist is not the same as this, you say?

Glenn: I wrote a chapter called ‘Gaia and the Ghedeist’ in Earth Emotions because many people have felt that the idea of Gaia is itself a spiritual reality, and it can become almost god-like. But like Margulis herself, I have my doubts about Gaia being animate in the sense that ‘it/she’ has intentions. You know, James Lovelock wrote a book called The Revenge of Gaia,[4] but I don’t think that we can talk about Gaia as being into revenge.

The sense I want to convey with ghedeist is much more to do with lived experience. My own life on Wallaby Farm is a good case study. I walk land which has been walked by Aboriginal people for tens of thousands of years. I sit on rocks that are millions of years old. I’ve got wallabies, koalas, reptiles, around me – koalas have been in Australia for 25 million years in various stages of their evolutionary development. So I have a sense of belonging to this place which goes back in time.

And I directly interact with the living things around me. I often walk with a camera and focus it on the eyes of the animals I encounter; it could be a two metre long lizard, or a brown snake that could kill me, or it could be a parrot which has the most exquisite colour and gaudiness of anything on the planet. And when I do that, I cease to exist as an individual, isolated ego. I merge into a world which is completely inseparable from me. This is a kind of seamlessness of experience that we can all have as humans in the world that we were born into – a world that has an ancient lineage and interconnections that we’re only just beginning to discover.

Jane: This question of interconnectedness suddenly seems to be at the forefront of our awareness in every way. There is a lot of scientific work now coming out now about it, for example.

Glenn: Yes, one of the things I am particularly interested in now is what is called ‘microbiome’ – the fact that we’re inhabited by trillions of bacteria, viruses and fungi which keep us alive just as much as a good glass of red wine. And the work of people like Suzanne Simard on the interconnectedness of trees, and the extraordinary cooperation between them and other organisms (see our review here).[5] She’s a fantastic source for understanding that the relationship between fungi and trees – and indeed humans if we behave properly – is not one of alienation and isolation. When we begin to understand the situation fully, we see that it is one of deep immersion, deep integration. These different life forms do not, and cannot, exist in isolation. We all work together to share a common life.

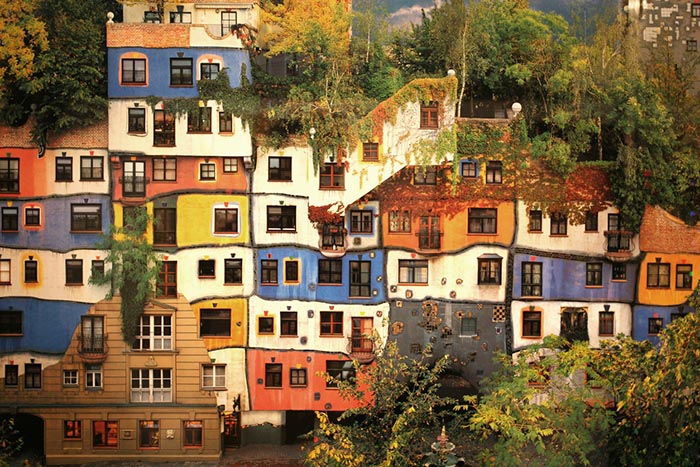

An apartment house built by Austrian artist and painter Friedensreich Hundertwasser in Vienna between 1983 and 1985. Photograph: MarcQuebec/istock

The Problem of Cities

.

Jim: I find this idea of ghedeist rather wonderful, and it’s part of the spirituality that I would live by myself. But the majority of people now live in cities, and this is a trend that is projected to increase in the future. There are already cities of 20 million or more people, and in many cases they are completely disconnected from any kind of natural environment. How can they develop any sense of connectedness to the earth?

Glenn: Well, Bill Rees, the Canadian ecologist who came up with the concept of the ‘ecological footprint’, has described cities in thermodynamic terms as entropic black holes, sucking in resources from the whole world and spewing out pollution and disease (see video right or below.) They are part of the story of gigantism and homogeneity of modes of production, the mode of economics, that we have worldwide now. You can’t write about the things that I write about without questioning that mode, and I don’t accept for a moment that cities as they are currently configured are going to exist for much longer. Critiquing them is essential to questioning the foundations of our relatively young – 300-year-old – system of economic production that has gone rogue: rogue in the sense that it’s now controlled by a tiny number of people that have a vested interest in its perpetuation.

Video: Resilient Cities: What if ‘can-do’ can’t? Duration: 37.44

People like Frank Lloyd Wright could see the problem 50 years ago. He understood that the dominant model of the megalopolis was not viable, and that it would ultimately consume itself in a kind of parasitic globalised form of mass destruction. So he argued for organic architecture. He suggested that we need to have things like high-density living but in his vision, the buildings are surrounded by farms. I am also inspired by the Austrian artist Friedrich Hundertwasser, who again is someone who rejected the idea that cities should be designed as a continuation of the box and the straight line – the nonorganic.

Jane: This is the man who designed the famous Hundertwasserhaus in Vienna?

Glenn: Yes. The box is the cheapest possible way of producing a structure, but it does not really consider the humanity of its residents, or indeed their connections to other life forms. There’s the spiritual dimension to life, and this needs to find its expression in architecture and engineering, and other ways that we must operate as humans.

In the book I am writing now – on what I call the ‘Symbiocene’ – I am devoting quite a lot of effort to thinking about cities and high-density living. We should be entropy-minimising our cities, not entropy-maximising them, and we need to build systems that are diverse and resilient. We know from complexity theory that if you make systems homogeneous, then it only takes one thing to go wrong for the whole thing to fail. The UK in recent months, I’m afraid to say, has provided us with a useful case study in this – how something as simple as a shortage of lorry drivers can bring society to a halt. And of course, Covid-19 is another example.

Lynn Margulis (1938–2011) giving the inaugural lecture at the Training Course in Science News, ‘Science in contemporary culture. The example of live sands’ in 2005. Photograph: Javier Pedreira [/] via Wikimedia Commons

The Symbiocene

.

Jane: Can we move on, then, to talk about your notion of the Symbiocene. In your book, you are critical of concepts like sustainability, or even resilience, for being too weak to make any difference, and too easily co-opted into the status quo as minor adaptions. You argue that what we need is a completely different approach.

Glenn: People talk about this being the age of the Anthropocene – the age when human beings have come to control the earth’s environment, and this has led us to our present state of catastrophe. I envisage the Symbiocene as the next age, where we learn to live in harmony with the rest of creation – when the idea of symbiosis, rather than competition, becomes the basis for our reconnection to the rest of life.

Jane: Symbiosis is the process through which two or more different species cooperate for mutual benefit – like plants and fungi cooperate to form lichen? Or fungi and trees cooperate in forests.

Glenn: Yes, it is important that symbiosis is not really a philosophical idea: it comes from science. It’s Lynn Margulis writ large. As we have just said, there is a lot of scientific work now that shows that life forms not only compete with one another, they also collaborate and work together. The more we understand symbiosis, the more we understand that that’s the future for life on Earth, whether we’re part of it or not. So I’m beginning to put together a book that explores ways in which we might re-integrate with the rest of the life-world and use our intelligence to convert everything that’s currently parasitic or cancerous – I mean in the metaphorical sense – to something which reconnects us to not only the shape of life, but the processes of life

Jim: Can you give us some examples?

Glenn: Well, I should begin by saying that this is not a fully formed vision; it’s a work in progress to see what we might be able to do. But if you consider the generation of electricity: solar power and wind power are much less dangerous and less destructive than coal-fired or oil-fired power but they are only a temporary solution. The next step is for bacteria to produce our power. They could be living in our walls making the light shine without any heat or any pollution. This is not just fantasy; these things actually exist now (click here [/] to read more). Or we could build with bricks made of fungi that self-repair. We’re beginning to see a possible world where everything would be biodegradable; where everything would be compost for something else, entirely non-toxic, repairable.

Jim: Glenn, I think it’s a wonderful vision that you’re putting forward – more than a vision, perhaps, as you’re getting into the nuts and bolts, the detail, that needs to be attended to if it is to come to fruition. But many people, such as Jem Bendell, who founded the Deep Adaptation movement [/], would say that we are in a race against time. The rate of environmental degradation is such that some sort of societal collapse is inevitable. So visions such as yours will be overwhelmed by catastrophic events – enormous sea rises, or methane burning off in Siberia, or whatever.

Glenn: Of course I accept this as a possibility. People talk a lot about the loss of biodiversity, but the massive issue before us is actually the loss of humanity itself, which I refer to as the seventh great extinction. But we are all working at the most uncertain, unknown edges of climate science and it is full of question marks. So I don’t hold that same apocalyptic vision of the future: I think that there is still a glimmer of hope.

I also think it’s an obligation on adults right now to offer a path for our young people, and we need a vision of the future that is so compelling that they want to get into it straight away. I believe that if we start to think in terms of the Symbiocene, we have the possibility of a future which is not only worth having in a practical and material sense, but which could also be beautiful, interesting and endlessly creative.

French Dream Towers, a proposal by XTU Architects [/] for a development in Hangzhou, China, featuring facades covered in panels impregnated with micro-algae. This patent-pending ‘bio façade’ technology involves introducing a layer of algae which both provides natural insulation, and also offsets the building’s environmental impact by absorbing carbon dioxide and producing oxygen. Photograph: Courtesy XTU Architects

The Tipping Point?

.

Jane: We seem to live between the two extremes of depression and complacency at the moment. Some people feel that the ecological situation is so dire that it is too late to do anything about it, so we need to adapt to a very different world. Others – which unfortunately still seem to be the majority – feel either that it is not urgent, or it can be fixed by a few technological innovations. Both of these are leading to a kind of inertia. Australia is still mining coal in Hunter Valley, for instance, and we are continuing to cut down forests and deplete our soil at an ever increasing rate.

Glenn: Of course we should be doing everything we can to stop the decline. We should have stopped coal mining 20 years ago and now we cannot afford another degree of warming. On Wallaby Farm, we try to live on our fruit and vegetables as best we can. But in recent summers we have had temperatures of 47 degrees here, and I have seen plants burn – literally burn – without there being a fire. I live with koalas, wallabies, snakes, lizards, parrots, and it has been recorded that birds just fall out of the sky dead because the temperature was too high. If COP26 fails, we are going to have an even warmer world, and our property – my life at Wallaby Farm – will come to an end because it will get too hot or we’ll burn.

So urgent is the need to reduce our carbon emissions I’m actually quite supportive of people who want to suck carbon dioxide out of the air with big, expensive machines because I think they’re worth the investment. They’re certainly a better investment than more coal-fired power stations that continue to pump the stuff out.

Jane: It’s not just a question of new ideas, though. There are huge vested interests in the present system and people are not going to give it up easily. How do you see change happening?

Glenn: Well, I think change is inevitable, because, as I have already said, our present systems are extremely fragile. Facebook went down for seven hours a couple of weeks ago and it was a global crisis. The question is how to make that change move in a positive direction.

In Earth Emotions I talk about it in terms of generations, and describe the young people who are growing up now as part of ‘Generation Symbiocene’. They are already throwing up great leaders like Greta Thunberg, and there are amazing kids here in Australia too. But they cannot do it by themselves. So there has to be a multi-generational collection of intelligent human beings that begin right now an effort to resist, first of all, the insanity and the destruction, and then begin to pull down our existing structures in order to rebuild.

During the 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s, there were tiny little movements through which people questioned the sanity of what was then a widely-accepted universal model of development. We’ve at least got to the point where that’s being contested – and it’s been contested publicly and openly by people of goodwill. I see this as a conceptual and practical leap forward.

Jim: Many people are seeing this decade as a tipping point: the last chance that we have to put things back on track.

Glenn: I don’t think the concept of a tipping point is all that useful in itself, but what it’s saying is that the forces that are destructive and the forces that are creative are now at least in some kind of equal balance. We could talk about this in terms of war, but I would resist seeing this as a literal reality. The situation clearly has potential for mental and physical violence, but I’m a non-violent person and I see war as entirely negative and useless. I hope that we avoid a final situation of MAD – mutually assured destruction – which would be the ultimate end of any nuclear war that humans engaged in.

But certainly, we’re at a critical point in our history as a species. If I only cared about humans, that would be enough. But I also care about the rest of the extant biodiversity on this amazing place we call the Earth. We humans may be able to adapt to a warmer world but most other species can’t – and I feel an obligation to them. I mean, as far as we know, with all of our interplanetary exploration and our deep space tracking antennae, this is still the only place we know that’s got life. I think it’s worth fighting for – and I will use all the tools that I have as a philosopher, a teacher and a writer to make sure that I don’t go down quietly.

Jim: So you will be devoting yourself to producing your next book on the Symbiocene?

Glenn: Yes. I see the Symbiocene as a culturally transmissible idea that could be attractive to people, and give them hope and radical anticipation of the future. And also give them something to do. There’s no end to the amount of work needed. We are talking about a change in our political structures and different forms of democracy that involve, for instance, the integration of considerations of other life forms. We are talking about a change in our educational structures, because the effort to create something like the Symbiocene is trans-disciplinary; it’s not going to happen in the universities as currently construed. And architecture – I am no expert, but I occasionally give guest lectures to the architecture students at the University of Newcastle in New South Wales, and they are just blown away by the creative possibilities of thinking differently about these things.

So instead of worrying about unemployment for the next God knows how many decades we’ve got, we could be imagining the new universities, the new jobs, the new training – the new everything – that’s required to bring this about. And we need to do this with a sense of commitment, so that we start to heal and repair the damage that we have done.

Glenn talks more about these ideas in his podcast ‘Expressing Our Earth Emotions and Cultivating Generation Symbiocene’ made in June 2021: click here [/].

—

And this is his classical TED talk ‘Tipping Points of the Mind’, given in 2010: click here [/].

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Glenn Albrecht on his farm in Hunter Valley, New South Wales. Photograph: Bob Beale.

Inset: The Australian Golden Whistler (Pachycephala gutturalis) illustrated by Elizabeth Gould (1804–41) for John Gould’s Birds of Australia. Image: Rawpixel via Wikimedia Commons.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] GLENN ALBRECHT, Earth Emotions: New Words for a New World. (Cornell University Press, 2019).

[2] JOHN GOULD, Birds of Australia (Seven Volumes). (London, 1840–48).

[3] GLENN ALBRECHT, ‘Solastalgia: A New Concept in Human Health and Identity’. (PAN 3, 2005, 44–59).

[4] JAMES LOVELOCK, The Revenge of Gaia: Why the Earth Is Fighting Back – and How We Can Still Save Humanity (Allen Lane (Santa Barbara), 2006).

[5] SUZANNE SIMARD, Finding the Mother Tree (Allen Lane (London), 2021).

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: The Black-Flanked Wallaby. Duration: 2:04

Video: Resilient Cities: What if ‘can-do’ can’t? Duration: 37.44

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

Paddling the Magic Canoe: The Wisdom of Wa’xaid

Briony Penn talks about her relationship with the native elder Cecil Paul – Wa’xaid – and their successful campaign to preserve the glorious Kitlope River area in British Columbia

Entangled Life

Dr Merlin Sheldrake talks about the remarkable world of fungi, and what they can tell us about ourselves and the interconnectedness of the world

The Unity of Bee-ing

An interview with Heidi Herrmann about the work of The Natural Beekeeping Trust in preserving our precious population of bees

A Biology of Wonder

An interview with scientist Andreas Weber, whose radical ideas are transforming our understanding of nature

READERS’ COMMENTS

Imagine a future in which all children were taught from birth to worship Gaia, or Pachamama, or some other version of the one evolving earth organism to which we all belong, on which we depend. Imagine a church for which natural history was the scripture and ecology the catechism.