Remarkable Lives _|_ Issue 16, 2020

Towards a Deeper Spirituality

The Reverend Peter Dewey looks back on a lifetime working with interfaith projects

Towards a Deeper Spirituality

The Reverend Peter Dewey looks back on a lifetime working with interfaith projects

The Reverend Peter Dewey (b. 1938) has been interested in the deep connection between the world’s spiritual traditions since childhood, and over the last fifty years has worked on an extraordinary range of projects which bring people from different faiths together. Amongst many other things, he was the first Chairman of the Beshara Trust, a founder member of the Interfaith Network, and now works with the Interfaith Seminary, training people for a new kind of ministry which embraces all the major religions. In this conversation with Jane Clark and Cecilia Twinch, he talks about his life, the remarkable people he has met along the way, and shares some of his insights into the deeper form of spirituality he believes can come about through interfaith dialogue.

Cecilia: How did you first become interested in interfaith matters? I read somewhere that it began when you were still a teenager.

Cecilia: How did you first become interested in interfaith matters? I read somewhere that it began when you were still a teenager.

Peter: Well, from an early age, I always believed that there was a source of ‘all’ from a religious point of view, or a God, however you want to put it. I did not ever have to be converted to that idea. This was partly because my grandfather was in the Church and partly because I went to church schools. But I never intended to enter the Church. I really wanted go into politics, and that was my ambition since I was about seven years old. Someone took me out to tea once from school and asked me what I wanted to be and I said ‘foreign secretary’, which of course caused great hilarity.

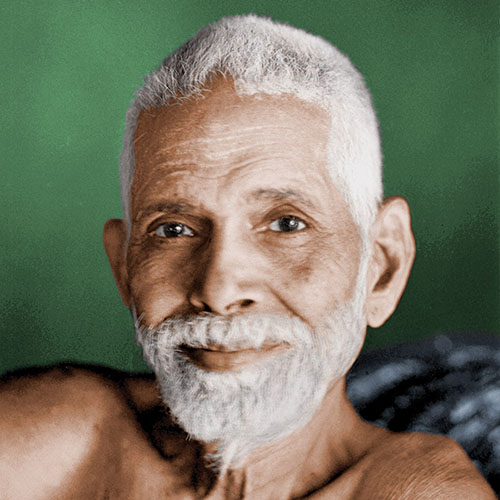

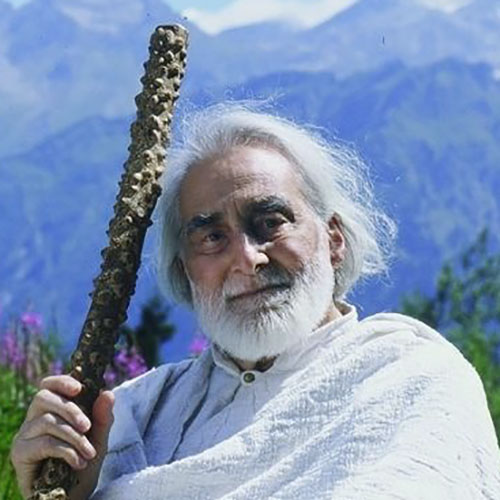

I started becoming interested in other faiths when I was about ten. I used to read a lot of books on spirituality, such as works on Vedanta. I also had an uncle who had been out in India during the war, and a great friend of his from Sri Lanka came to stay with us for a while. He was a pupil of the Indian mystic Ramana Maharshi [/], and he began teaching meditation in the UK, so he taught me when I was about twelve. That was the start of my spiritual education. He was running a group in Earls Court which I joined from time to time, and later, took over.

Sri Ramana Maharshi (1879–1950)

Jane: So how did you change from having political ambitions to becoming a priest?

Peter: I went straight into National Service from school, where I became a subaltern in the Royal Signals, and served in Cyprus during the troubles there. I did not go to university, but when I came out of the army I looked for a job which would support me whilst I launched my political career. I ended up doing a management training course with the John Lewis Partnership and worked for them for about ten years.

At the same time, I joined the Young Conservatives in Chelsea, which in the 1960s was rather a shabby place, not the up-market area it is today. I had a pretty promising start. When I was about 26, I fought a local election there and was voted in as a borough councillor. This gave me some status, as it was a Labour area and I had not been expected to get in. So after a while, I was invited to fight a parliamentary seat in Manchester Exchange. There was no chance of winning, but the idea was that I would get bloodied and be ready for a more likely seat later on.

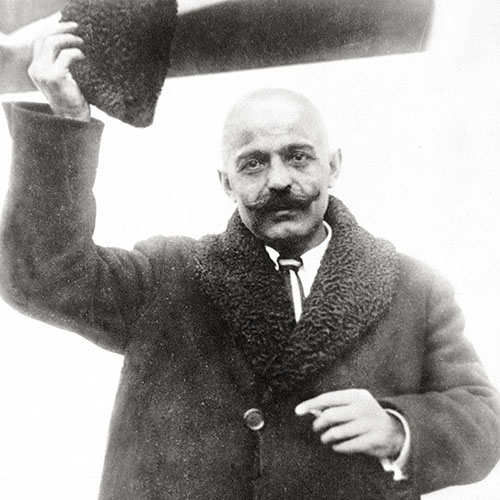

But then I got tuberculosis, which put me in a sanatorium in Midhurst for a year. The treatment then was still very old-fashioned; the drugs we have these days weren’t available so it was all injections in your backside and sitting with all the windows open watching the squirrels coming in and eating your grapes. It was during this period that I read all of works written by the Georgian teacher, Gurdjieff, who was very influential in the early years of the twentieth century. Having already learnt to meditate, and also having already looked at Vedanta and Ramana Maharshi’s teachings on ‘who are you?’ [1], I just loved Gurdjieff [/], and became very enthusiastic about it all.

Then one day, my doctor said: ‘There’s a man upstairs who has a heart problem and needs someone to talk to. Would you be able to do that?’ So as I was up and about, I rather reluctantly made contact. He was an Anglican priest, and I spent at least two months with him, helping him to walk and such like. We talked a lot, and at one point he said to me: ‘I think you ought to be ordained’.

This was a crucial moment for me, because about ten weeks earlier I had found a cellar where I could meditate – it was actually an old chapel with pews and so on – and I had decided that I was going to make a change. I made an inner vow that I would offer myself to the Church, even though I did not have the right qualifications. But I wanted a sign that I was doing the right thing, because I still in some ways wanted to do politics. I used this as a get-out clause, as I knew that we don’t really get signs and I was safe. So when he said ‘I think you ought to be ordained’ my whole body froze: you get a chill down the spine when these things actually happen.

Then it was made very easy for me. My friend arranged everything, and got me into Wycliffe Hall in Oxford to do my training. This was in 1969.

George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (1866–1949) greeting America on his arrival at New York harbour, 15 January 1924. Photograph courtesy of The Gurdjieff Foundation of New York [/]

Jane: So even though you had been so interested in Eastern traditions like Vedanta and Gurdjieff, you still decided to enter the Anglican Church?

Peter: I felt that I wanted to introduce something of this deeper spirituality into the Church of England, although I have to say that my motives were not very developed in the beginning.

Jane: But was the Anglican Church at that time not deeply suspicious of anything to do with meditation?

Peter: Yes, and especially places like Wycliffe, which is very much dedicated to the evangelical side of things. For instance, they were actively opposed to the word ‘meditation’ because it comes from India, and I learnt fairly early on to use the word ‘contemplation’ instead. However, I did run a meditation group in the Roman Catholic Priory, Blackfriars. Later on, of course, the Church became very keen to interact with the other faiths – the phrase was ‘interfaith dialogue’ – and so I was able to fit safely into that pigeonhole.

Jane: You must have felt quite isolated in the college, though.

Peter: Well, I was confident enough to survive it, as the overall spirituality was growing very strongly by this time. In addition, there was an interregnum during my time there and things were more relaxed than usual. Nevertheless, I used to hide my books on Gurdjieff and Sufism, and it was just as well, because I learnt later that my tutor had gone into my room one day and searched it. He did this because the college were puzzled by some of the ideas that were appearing in my essays and became curious about where I was getting them from.

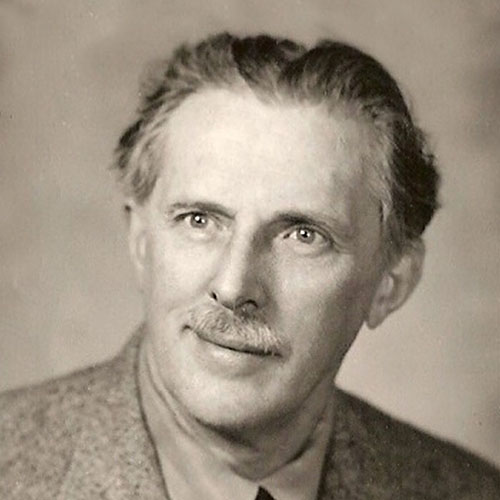

John G. Bennett (1897–1974). Photograph courtesy of The Estate of J.G. Bennett and Elizabeth Bennett [/]

Christianity and Islam, 1969–75

.

Cecilia: This was the time when you began to be involved in Sufism?

Peter: Yes; before I went to Wycliffe, I had already become involved with an Idries Shah Sufi group which met in London. I met Shah [/] through another friend, John Bennett [/], who had been a direct student of Gurdjieff’s. Bennett financed Shah’s work and helped him to buy a house in Tunbridge Wells through the sale of his centre, Coombe Springs. There Shah settled down to write the books for which he became famous.

I attended his group there for a short while. His place was quite a scene; celebrities used to fly in from all over the place by helicopter, which in the late ’60s got coverage in all the newspapers. But what he was actually doing, I realised later, was using the celebrities as publicity so that the books sold well and he could get the teachings across. He felt that he had a mission – and he succeeded in it: he sold masses of books, and Nasrudin and his donkey and all the stories about them became well known because of him.[2]

Then, whilst I was still at Wycliffe, I became involved with the Sufi Order of the West [/], which had been founded by Hazrat Inayat Khan. They had meetings in London, and through them I met Reshad Feild [/], and later Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan, who was the head of the order. During a conversation with these two, the idea came up of a centre in the country where the relationship between Christian mysticism and Sufism could be explored. I was accepted into the London Sufi group because of my Christian connection, and also my general interest in the mysticism of all religions.

This project led eventually to the setting up of the first Beshara Centre at Swyre Farm in Gloucestershire, which was established in 1971 as an open centre – meaning, a place where people of all faiths could go and study the mystical traditions of the world. The name ‘Beshara’ was given by Bulent Rauf [/] who had been brought in by Reshad to act as a consultant; he described the meaning of the word as the essence of divine blessing.

Jane: You were in fact the first chairman of the Beshara Trust [/], which is still going strong today – as can be seen by the fact that it is the publisher of this magazine.

Peter: Yes. After a while Bulent had the idea that something more focussed was required and hit upon the idea of running courses based upon mystical teachings, particularly Ibn ‘Arabi [/]. So they needed places to run these, and I helped with the setting up of, firstly, Sherborne House in Gloucestershire, which Beshara took over after John Bennett died in 1974, and then Chisholme House [/] in the Scottish Borders, which is still running as a place of spiritual education.

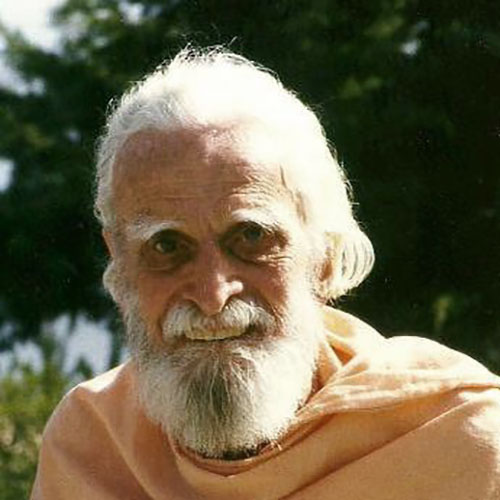

Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan (1916–2004)

Cecilia: Am I right in thinking that you also took a trip to India around this time?

Peter: Yes, when we first started talking about some sort of centre, I was concerned that I was not initiated into Sufism. So Reshad felt that I should make a commitment to the Order by visiting the grave of Hazrat Inayat Khan in Delhi, which I did. But this was not my first journey to India: I had been some years previously to visit the ashram of Ramana Maharshi and the sacred mountain, Arunachala, in Tamil Nadu. I had also visited Shantivanam, the ashram of Father Bede Griffiths [/], the Benedictine monk who was trying to build bridges between the Christian and Hindu traditions. I came to know him quite well; when he came to the UK, I would visit him at the centre in Abingdon which he helped to found.

The other person I was just starting to know at this time was George Appleton [/], who was a former Archbishop in Western Australia and later the Anglican Bishop in Jerusalem. He was then the interfaith advisor to the Archbishops of Canterbury and York. He helped me with the interfaith side of things within the Church, and remained a source of support for many years. After I had been ordained and was working in my first parish, I started my first meditation group there with the aim of introducing the practice into the Church. I also founded The Interfaith Association – basically for clergy in the Oxford diocese – and we started to arrange conferences and such like.

Chisholme House in the Scottish Borders, which was set up in 1975 to run intensive courses in spiritual education for the Beshara Trust. Photograph courtesy The Chisholme Institute [/]

The Purpose of Interfaith Dialogue

.

Jane: So in this period – late ’70s – you have mentioned that there were moves within the Anglican Church to encourage interfaith dialogue. I know that within the Catholic Church, contact with other faiths was also being very actively promoted following Vatican II.

Peter: Yes, it was becoming very much ‘the thing’ at this time, although it was seen that dialogue was possible with some faiths and not others, and evangelicals of course were very much against it.

Cecilia: What do you see as the purpose of interfaith work?

Peter: My own aim was always to broaden everybody’s outlook to see that everyone is a child of God. But nowadays interfaith dialogue is much more to do with peace and living in harmony. I don’t think there is a real desire to speak at a deep level to each other. However, there is a feeling that it is right to be having some sort of conversation. But even this degree of contact was not common when I first entered the Church; many people felt that it was wrong to even be in the same room as someone from a different faith, because one would be tainted.

Jane: So what do you see as the basis for contact between faiths?

Peter: My point of view has been evolving since the early days. It began with the realisation that the presence of God is there in every religion. But it has been corrupted by different cultural systems, politics, and all sorts of wrong thinking that gets added into the religion over time. So you have to search for it – I mean the presence – within all these accumulations. In the mystical traditions there is more pure thinking, and so it is easier to perceive.

Having got that understanding, when I went on to look at Islam, it seemed at first very different and even rather frightening. It was the Sufi teaching which helped me to understand what was happening. The teaching of Jesus is that the presence of God is within us – he tells us to awaken to the presence within us, the Christ within us – and there is also the matter of the second coming, which is yet to happen. At least, people feel that the second coming has not happened yet. But what is the second coming? In an interior sense, I believe that it is when you so desire to do the will of the presence within you, and to become a part of it, that you get married – you enter into a marriage and become one.

So the second coming is when you come to surrender completely to the love of God. There is no bargaining at this stage; it is a complete surrender and you have to give yourself totally to it. Of course there are days when you don’t, so it is a continuous action of deeper and deeper surrender. What Jesus calls ‘entering into the Kingdom’ is really a process of going deeper and deeper into the spirituality; there is no end.

Jane: So how do you see the connection with Islamic mysticism?

Peter: Well, what is the Arabic word for surrender? It is islām. So this is an indication of this next stage, of giving oneself up completely to God. I am not talking here about Islam as a religion – at least not as the outer form of the religion. The thing about these spiritual truths is that they are not usually common knowledge, but they are protected or kept hidden, preserved within particular groups. And within Islam, this group is the Sufis. This is not to say that Sufism is perfect in every way – far from it – but it seems to me that the teaching and the way of evolving spirituality has been preserved within the tradition for the time when it will become the norm and will not be seen as heretical by the fundamentalists or the Sunni orthodoxy.

We are talking, perhaps, about quite a long period of time before that actually happens. But the important thing is that this deep spirituality is already there. It is one of the great errors of our thinking that we expect that everything should happen instantly. It is the same with politics: we judge everyone by our own standards and do not judge them according to the way that they are evolving. We should recognise that people, religions, countries, are all evolving, so they should be allowed to evolve and given help in the process.

In terms of the evolution of the world, our own lives are very short – like a butterfly’s – and it is the ego that demands that everything must happen in our own lifetime. Once you get rid of that egocentric point of view, it is easier to understand what is happening and take a long view.

Jane: So you would see the second coming as basically an interior event, which can happen to someone at any time. But do you understand it also as something that will happen in history, in the future?

Peter: Yes. At a personal level, it is to do with entering within yourself into a deeper level of spirituality. Gurdjieff talked about spiritual evolution in terms of octaves, and so you could say that the second coming is the point where you enter into a higher octave and realise that there is a whole new process of development to go through.

The Jesus teaching is that this level of realisation happens to only a few people at any one time: ‘Many are called but few are chosen’ as it says in St Matthew’s Gospel.[3] But at some point, a large number of people will come to it and begin to follow it. Then it will be seen as a challenge to the religions, and this will create friction. So the deeper the spirituality, the greater the resistance will be.

Idries Shah (1924–1996). Photograph: Ramsay Wood, courtesy of the Idries Shah Foundation [/]

The Deeper Spirituality

.

Cecilia: How do you understand the extraordinary expansion of knowledge about the mystical traditions which has happened over the last fifty years or so – the fact that the teachings of all the world’s wisdom traditions are now freely available for people to read and study? Do you see this as a preparation for this time?

Peter: Well, as a preparation for going deeper in terms of spirituality. One of the characteristics, I believe, of this deeper form of spiritual understanding is that it will include the full diversity of people working together and being together. This is the ‘global village’ that people like Marshall McLuhan talked about in the 1960s. It is a ‘spiritual school’ for developing this higher form of understanding at the next level.

Jane: And this is where you see the importance of interfaith work?

Peter: Yes. Interfaith work is partly to do with just looking at all the different modes of expression that have come about over the millennia, and partly to do with developing a universal form of spirituality. In order to do this, people have to move beyond the religion of their upbringing, which can be seen as their parent. Now the teaching of all the religious traditions is to love our parents, because they have given birth to us and enabled us to get where we now are. So we must always honour them, and even though we might want to move away from them or even come to think that some of their teachings are actually wrong, there should be no hatred towards them.

One of the things that is clearly happening in the Christian world today is a kind of collapse of the outer structure of the religion, and this creates the freedom, the space, for other ways of thinking to emerge. An important aspect of the interfaith movement is that it provides a place of development for people who are moving away from a faith that they believe has become moribund.

Jane: But these days many people do not think of themselves as being attached to faith at all. Either they were not brought up within a religious environment, or their reaction to what they see as a moribund institution leads them to abandon faith altogether.

Peter: Well, my main thought about this is that everyone is evolving. Looking at all the different religions and the different ways, and seeing them from a Christian point of view, my understanding now is that the presence of the Christ energy is in all of them. It says in St John’s Gospel ‘Before Abraham was, I am’.[4] The ‘I am’ is God’s name; it comes from the Old Testament, the revelation to Moses. Many people these days maintain that the ‘I am’ refers to Jesus, but what is actually being said is that God is always the way, the source.

Father Bede Griffiths (1906–1993). Photograph: Oblates of Shantivanam [/] © Roland Roper

Interfaith Work, 1970–90

.

Jane: Returning to your life story: after your training at Wycliffe, you became a parish priest?

Peter: No, I became a chaplain to my bishop in Kensington, and that was a very good education, because I went round with him to all the different churches and saw the many different ways that they operated. One day we were dancing in the pews and the next we were incensing the altar, so it taught me to look at the essence of things. Then I went to Clifton Hampden in Oxfordshire where I looked after four churches. At the same time, my friend who had taught me meditation had gone back to Sri Lanka, so I took over his group in London. In fact I was running about ten or twelve groups during this period, most of them meeting monthly.

Jane: Was this a Christian form of meditation?

Peter: No, it was basically transcendental meditation. This was the kind of meditation that was made so popular during the 1960s and ’70s by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi [/]. I saw him once in person; he gave a talk at the Albert Hall to which all the bishops of London were invited. None went, of course, but my bishop said that I could go as his representative, so I sat right at the front in an official position. One of the perks of the job!

Cecilia: One of the few facts about you that can be found on the internet is that you worked for a time at Gordonstoun School.

Peter: Yes; after ten years at Clifton, it was time to move on, and I took up the post of chaplain at Gordonstoun in Scotland. But that went wrong for me because of my interfaith work. The Tibetan Buddhists had set up their centre in Samye-Ling in the Borders of Scotland, and in 1992 they were given Holy Island [/] in the Firth of Clyde to be a place of retreat. They wanted representatives of all the different religions to attend their opening ceremony and bless the island. So they asked me to be the Christian delegate, because I had been doing a lot of work on retreats on Iona nearby, which, as you no doubt know, is an important Christian centre; the abbey there was founded by St Columba in the 6th century. But the ceremony generated some publicity in the Glasgow newspapers, and this was seen by people at Gordonstoun. The evangelicals amongst them started to object to my role at the school, so I had to resign.

Centre for World Peace and Health on Holy Island, established by the Samye-Ling Buddhism Community in 1992 as a place for retreat and conservation. Photograph: Sarah Lionheart via Wikimedia Commons

Jane: You have had other trouble with the evangelic wing of the Church I believe.

Peter: Yes, earlier on, in the late ’60s, when I was involved in the Interfaith Association, with the help of George Appleton we ran a series of conferences in St Albans Abbey, bringing representatives of different faiths together. But the evangelical groups stopped it after two years, because they said that the constitution of the Abbey forbade people of other faiths from stepping foot inside the building. In the second year, they marched around the Abbey with placards whilst we were talking inside!

But we moved to another conference centre and carried on. Then in 1987, Tony Blair became Prime Minister and he was very keen on interfaith relations. So he asked one of his retiring civil servants to set up a network for all interfaith groups in the UK, which became the Interfaith Network [/]. This chap came to interview me and we found that I already had the leaders of all the religious groups on my list of patrons. So although I was not a religious leader, I was allowed to be a founding member and attend meetings. This meant that I was able to rub shoulders with all the interesting people who became involved in it.

The ordination ceremony for the 32 people who graduated from the Interfaith Seminary in 2018. The event took place at the Great Hall at Reading University on Saturday 21 July. To see a short video, click here

Interfaith Ministry, 1990–present

.

Jane: After Gordonstoun, you came back to the south of England and have remained here ever since?

Peter: Yes, I came back to Oxford and worked in various parishes up until my retirement a few years ago. On the interfaith side of things, the focus of my work changed in the 1990s and I began to work with Miranda Holden to set up the Interfaith Ministers Seminary [/], which trains people for ordination in an interfaith ministry. This involves an education in all the major faiths, and I taught the Christian part of the course, as well as helping with the general organisation. This movement began in the USA, and so I had to travel over to New York to the headquarters for ordinations and such like, which was fun.

Jane: Out of your work for the Seminary has come a very rare piece of public communication from you, as you have made a film on the meaning of St John’s gospel with the psychologist Robert Holden (see video right or below). But I have not been able to find very much else – no articles or books, for instance.

Video: Gospel of John – Decoded and Revealed. Duration: 2:03:46

Peter: Well, the reason for this is that I am very dyslexic and I don’t write. I have never written a sermon, for instance.

Jane: So how have you managed to be a parish priest for what? Nearly fifty years?

Peter: It just has to come to me in the moment. If it doesn’t come, they don’t get a sermon and I go red in the face! At the beginning, doing it like this was a bit of an adrenalin rush every time, but after so many years it is easier. You can do this if you know your subject and are happy with it. You can’t do it properly when you are learning and full of questions about things; then it is hard to speak with the whole of your being.

Jane: So are there more things in the offing?

Peter: This film is meant to be the first of three, which will be made over the next two years. I am not sure yet of their themes; I would like perhaps to do one entitled ‘Life, Death and the Afterlife’.

Jane: So finally: what are you thoughts about the future of interfaith initiatives? One of the things which has struck me as we have talked is how many of the projects you have been involved in are still going. You have mentioned that much of the dialogue conducted under the umbrella of the government or the Church now is motivated more by politics than a search for real meaning, but there is still a lot happening on the ground.

Peter: There is no doubt that new forms of spirituality have started to become established; there are spiritual groups all over the place, and at the same time the Christian Church in particular seems to be dying. Of course, once there are so many groups, you also get wrong ones – groups who are doing things for less than good reasons – and so there is a certain degree of chaos. But I see this as a necessary stage, as it is only in chaos that spirituality can actually come out.

Things are going through a change at the moment, and I am not sure which way they will go. There are lots of people looking for a deeper form of spirituality and it is really for these different groups to take matters forward.

St Mary’s Church in Sulhamstead, Reading, in the parish where Peter served for many years. Photograph: babelstone via Wikimedia Commons

Image Sources (click to close)

Banner: Peter outside his house in Berkshire. Photograph: Cecilia Twinch

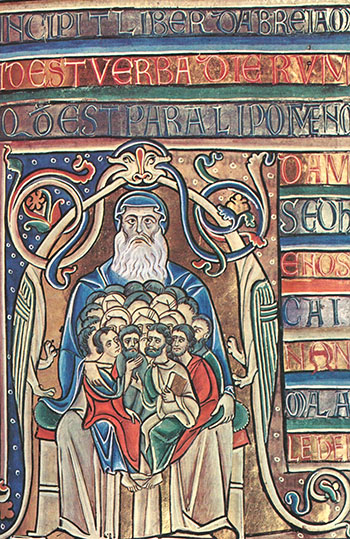

First inset: An early affirmation of interfaith unity. Twelfth century miniature showing Muslims, Jews and Christians in Abraham’s lap, from the Bible de Souvigny. Image: Bibliothèque des Moulins

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] See RAMANA MAHARSHI: Be As You Are (Penguin Books, reissued 1988).

[2] See for example IDRIES SHAH: The Exploits of the Incomparable Mulla Nasrudin (ISF Publishing, reissued 2018).

[3] Matthew 22:14

[4] John 8:58

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Gospel of John – Decoded and Revealed. Duration: 2:03:46

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

The Unity of Humanity

Professor Todd Lawson on the universal vision of the Qur’ān

A “Quite Interesting” Approach to Education

John Lloyd talks about the philosophy behind the QI project

Mysticism in Comparative Perspective

Professor George Pattison talks about the revival of a unitive approach

Choje Akong Tulku Rinpoche

Vin Harris talks about the life of a remarkable man

READERS’ COMMENTS

This is a marvelous interview, bringing a remarkable insight into modern spirituality .

I met Peter during my schizophrenia in the early seventies. I think he may like to meet me again to reflect on our interactions. My early experiences with him are in The Harrowed Path taking place at and near the original Beshara Centre (Swyre Farm)

Hi, is there any chance of contacting Peter privately as I believe he had some adventures in the 1960s with my dad Kevin Patrick Lawlor. KP left us when we were little and now we’re trying to get a sense of the person and his adventures. Thank you.

Must have been when he was Very Reverend Derek Hayward’s curate?

Surely a man of depth, width and humanity runs through and through. Thank you Peter for your life of service.

I met Rev Dewey when he was Very Rev Derek Hayward’s curate. Was most impressed.

I would love to be in contact with Peter. He was Chaplin when I was at Gordonstoun and I have very positive memories of him. He is an incredible man.

What an informative interview, thank you. I knew of the name through my involvement in Beshara but I knew nothing of the man and his work.

Thank you for this stirring, inspiring essay of the man and his life’s work. My first connection to ‘the second coming’, having been born into a Jewish family, was in the kitchen at Swyre Farm, having come to it to recoup after splitting from husband and children. At that time you could claim unemployment income, so I stayed, and then took the next step, the 6 month course at Chisholme, which was just beginning together with restoration work on the house. It was the start of my spiritual journey, which still continues. In the last paragraph he mentions this time of change, which includes now for me channeling from those who have already passed over, together with the possibility of meeting other civilisations beyond our own planet. Interfaith takes on a new meaning!