Remarkable Lives _|_ Issue 26, 2024

Radical Hospitality: In Memory of Rosemary Haughton (1927–2024)

Phoebe Ryrko remembers her grandmother, an inspiring theologian and activist who saw the divine in everyday life and human relationships

Radical Hospitality: In Memory of Rosemary Haughton (1927–2024)

Phoebe Ryrko remembers her grandmother, an inspiring theologian and activist who saw the divine in everyday life and human relationships

Rosemary Haughton, who died in May this year, was a distinguished theologian and activist who pioneered a radical view of the religious life. Brought up within a family of artists – and a talented painter herself – she underwent a conversion to Catholicism in her teens and rose to prominence in the 1960s and 70s with a stream of books that put forward the idea that theology should be based not on dogma and doctrine but on the experience of everyday life and human relationships. Above all, she saw love as the most important force in spiritual life. She fought against the marginalisation of women both in the church and in society; was admired by Thomas Merton; founded two innovative communities for the mentally ill and the homeless which still survive today, and brought up twelve children (ten of her own and two fostered). In this article, her granddaughter, Phoebe Ryrko, pays tribute to a remarkable woman whose ideas seem as relevant and challenging today as they were sixty years ago.

I feel very privileged to have the opportunity to write about my grandmother Rosemary Konradine Luling Haughton, who died on 9 May this year at the age of 97. She was an extraordinary woman: a mother and foster mother, an aunt, a sister, a lover, a wife and a friend, as well as a grandmother/great-grandmother to myself, my children and my numerous cousins. At the same time, she was a theologian who wrote 35 books and countless articles and talks, and the founder of two spiritual communities for the troubled and the homeless which continue to this day. Her life and work were radical at the time, and remain radical even now, rethinking love, salvation, sexuality, the divine in the everyday and perhaps most essentially, hospitality. Thomas Merton described her work as:

I feel very privileged to have the opportunity to write about my grandmother Rosemary Konradine Luling Haughton, who died on 9 May this year at the age of 97. She was an extraordinary woman: a mother and foster mother, an aunt, a sister, a lover, a wife and a friend, as well as a grandmother/great-grandmother to myself, my children and my numerous cousins. At the same time, she was a theologian who wrote 35 books and countless articles and talks, and the founder of two spiritual communities for the troubled and the homeless which continue to this day. Her life and work were radical at the time, and remain radical even now, rethinking love, salvation, sexuality, the divine in the everyday and perhaps most essentially, hospitality. Thomas Merton described her work as:

… an existential theology of love and encounter… a fundamental statement and witness to the salvation event in daily life and in areas where, to an exclusively clerical theology, it was not previously visible.[1]

Her childhood was bohemian. Her parents were artists, chaotic and creative. Her mother, Sylvia Thompson, published romantic fiction and undertook book tours in America which surely became a precedent for Rosemary’s own in later life. Her father Theodore Peter Luling was a watercolourist, print maker and antique dealer. Rosemary and her sisters Elizabeth and Virginia were raised in part by a loving grandmother Ethel Levis (Gigi). She travelled extensively and her schooling was sporadic.

Rosemary was always identified as a painter by her mother and it was Elizabeth who was seen as the writer, becoming at the age of seven the youngest person ever to have published a book. It was a story about her teddy bears and it was called Do Not Disturb. Sylvia wrote in the introduction:

At twelve o’clock Elizabeth had written the first chapter.

And after that she wrote every morning.

Rosemary said, ‘I can’t understand Elizabeth writing when she doesn’t have to!’

Rosemary is an actress and a Sculptress and an Engineer and a Doll’s Dressmaker and a superb

Omelette maker: but she HATES writing.[2]

Rosemary (left) and Elizabeth (right) with their mother Sylvia Luling in 1936. Photograph courtesy of the Haughton family

Conversion and Early Influence

.

As a young woman, Rosemary studied art at the Slade in London and then in Paris. She painted and carved beautifully. Her conversion to Catholicism took place when she was 16 and was simultaneous with her mother’s. But the seeds of longing and curiosity were planted long before, at the age of five, when a Roman Catholic family friend took Rosemary and Elizabeth to visit local churches. The gilt and the candles, the special smells and particular atmosphere stayed with her. Later, in 1934 when spending the summer in Venice, she was again struck by the sense that something important was in that space, something she needed to find out about.

Suddenly there flared up in my mind a great longing which I had known before, obscurely, but which I could now identify more nearly. I wanted to know this ‘important something’ which lived between the candles and the statues and in which the black shawled women immersed themselves.[3]

Her childhood seeking for God had been a secret affair, but in 1943 she met an ancient and tiny Benedictine nun, Mother Raphael, who became her spiritual instructor. Mother Raphael was based in Tyburn Convent, a monastery situated right in the heart of London, near the famous site of the Tyburn Gallows where more than 100 Catholics were martyred during the Reformation.

After the war, while studying in Paris, Rosemary discovered a circle of friends with whom she could discuss her new thoughts. These were inspired by Christian philosophers such as Jacques Maritain [/], who advocated what he called ‘Integral Christian Humanism’, Gabriel Marcel [/], a Christian existentialist, and Charles Péguy [/]. All three combined fervent Catholicism with socialist politics.

On her return to London, she met Algenon (Algy) Haughton through her life-long friend Jennifer Jennings (‘Jen’) who was teaching at the school where Jen’s father was headmaster. Algy was American born, raised by the Plymouth Brethren, a strict evangelical sect, who had discovered and converted to Catholicism while serving in the navy during WW2. They were married in 1948 when Rosemary was just 21, and had ten children together, plus a further two for whom they acted as foster parents. Quoting from the eulogy written by her eldest daughter, Susanna Dammann;

Algy met her and wrote in his diary that she was the most beautiful woman he had ever met, they married shortly after in a chapel in Westminster Cathedral.

In their wedding photographs with her shapely waist, full lips, large eyes, and dark hair Rosemary and the boyishly handsome Algy are a match in optimism and beauty.

The Theology of the Everyday Life

.

Rosemary’s career as theologian started ‘almost accidentally’. As she herself describes:

The couple who ran the school in Surrey where Algy got his first teaching job often invited us to dinner to meet their friends. One was Michael de la Bédoyere, an editor who had turned the regional Catholic Herald into a challenging, intellectual publication with a national circulation. Based on our dinner conversations, he’d asked if I would like to write some reviews, then an essay for a collection in which adherents of various religions or philosophies critiqued their own belief systems. I critiqued Catholicism in a piece called ‘Freedom and the Individual’, denouncing the church as authoritarian and calling for freedom of conscience. Reviewers gave my contribution particular praise. That’s how my writing career took off.[4]

Books quickly followed – Trying to be Human [5] in 1966 and The Transformation of Man [6] in 1967 – and before long she became an established theologian, particularly in America. Daniel Callahan wrote on the sleeve note of The Transformation of Man:

Rosemary Haughton has risen spectacularly in the past few years to one of the highest positions in the contemporary theological world. Her contention is that if theology does not make sense in terms of experience then it has no meaning at all.

Her unique approach was to start not with dogma or doctrine but with everyday life. For her, our ordinary, lived experience is the place where we meet God, and the means by which we can become transformed beyond the process of individuation imposed upon us through social and political structures, family, culture, science, etc. God is above all the transformative power which allows us to become ‘the whole human being’. She writes:

Transformation is a total personal revolution. It begins with repentance… and proceeds eventually to the desired dissolution of all that ordinary people ordinarily value in themselves or others. The result of this dissolution, this death of the natural man, is the birth of the whole human being, the perfection of man, meaning both man as an individual and man as a race, because the process is at once personal and communal.[7]

In The Transformation of Man she created ‘real people’ with history and family dynamics and personalities to illustrate how the encounters that happen in life give us opportunities to become more fully human. She shows how life pushes us so that we have a crisis – whether emotional or physical – and how through that ‘crack’ a conversion encounter can take place. One of the characters demonstrates how this can happen when he decides to explore the interests of his politically anarchic daughter, who is helping the homeless. He does not allow the spark of inspiration to mature at first but subdues it, and then becomes depressed and angry, drinking to escape. He gets drunk and is hit by a car, going to hospital, where he is given a tract from the Bible by his evangelical nurse:

So, he meets love expressed in Christian words and the words stir memories of his childhood, when he was loved, and loved by a woman to whom the words of the Christian faith were a natural way of expressing love and concern. He encounters Christ as the one who cares and who wants him.[8]

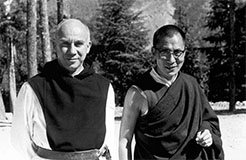

The success of these early books meant a welcome augmentation to the family income at a time when Algy and Rosemary were struggling to bring up a large family. It also led to many offers to give lectures, first in the UK and later in the USA. It was during such a tour that Rosemary had the chance to meet one of her childhood heroes, Thomas Merton. She described how as a teenager she had ‘encountered’ Merton and became ‘somewhat intoxicated with him, and then, as it were, “grew up” with him, as he struggled, explored, and changed.[9] She viewed him as: ‘… a sign and guarantee of the still, vivid, and incorruptible heart in a religion that had all too many obviously deathly and trivial aspects’.[10]

She had contemplated writing to Merton (Father Louis, Tom) for many years but refrained as she felt it self-indulgent rather than a pleasure for him. But she did finally write to him requesting that she might visit him at his monastery in Gethsemani after her 1967 tour. He affirmed her theology of experience, writing:

I hope you will continue to give us theology in people and things people do when they are most alive – not when they are only half conscious. Though that can be theological too! [11]

Their letters are full of mutual respect and admiration. She wrote back:

It was an immense encouragement to me to find that you valued the kind of thinking I’ve been doing & felt that it was moving in the right direction. Of course, many people feel (& say) that’s not theology, it’s about people. One reviewer said this & intended it as a compliment. I’m battling with the rooted & culturally immovable conviction that if it’s theology it can’t be relevant to human life.[12]

Merton wrote in his journal entry of October 27, 1967: ‘She is quiet, intelligent, not the obstreperous kind of activist progressive, concerned about a real contemplative life continuing’.[13] He took on board her idea that ‘Theology really happens in relations between people’, and wrote to his publisher Hugh Garvey: ‘Historians of theology will quite possibly look back on our age as the “Age of Rosemarys”… Or perhaps the “Age of the Mothers of the Church”’.[14] (For more on the relationship between Rosemary and Merton see video right of below.)

Video: Jim Robinson: Thomas Merton’s Engagement with Rosemary Radford Ruether and Rosemary Haughton; duration 21:08

Portrait of Rosemary taken by Thomas Merton on her visit to Gethsemani in 1967. Photograph courtesy of the Haughton family

The Drama of Love

.

In the Drama of Salvation, written in 1975, Rosemary explored the dynamics of salvation and how the seminal events of our lives such as birth, marriage and death fulfil the Christian promise of salvation, and, as rituals, move us from the personal to the communal. Our relationship with God has forms and shapes, such that from birth through to death we are engaged in a meaningful play, a kind of theatre or divine drama:

People who deny that death has any particular meaning are at pains to suppress the dramatic aspects of it, because these give it meaning… [Whereas] to all groups whose way of life was consciously centred on God, the deathbed mattered because it was proof to all – especially to as many as could squeeze in to witness it – that salvation was real.[15]

She compares the role of the spiritual seeker with that of an actor. Actors who are content to give a reasonable performance, who rely on technique and craft, are of a different sort to those described by Peter Brook [/], (the theatre director) whom she quotes as saying:

The really creative actor reaches a different and far worse terror on the first night. All through rehearsals he has been exploring aspects of a character which he senses always to be partial, to be less than the truth – so he is compelled, by the honesty of his search, endlessly to shed and start again.[16]

So also, Rosemary maintains, the committed believer…

… searches all his life for the truth, the Kingdom of Heaven, the self within, which he can never know more than partially in mortal life, and yet which empowers and transforms his thoughts… Like any other human being, the committed believer fears the revelation of his basic nakedness, which is ultimately the nakedness of dying; but for him death is not a single far-off date to be prepared for but a constant companion.[17]

Rosemary’s most radical commitment, though, expressed in her 1981 book The Passionate God,[18] was to the idea of love as the most important force in spiritual life. She maintained that the divine love can be expressed in all human relationships, unfolding in community, in the church, in the family, and not least in the intimate encounter that is sexual. The knowledge that is direct, intuitive and experiential, in contrast to the indirect knowledge gained through intellect, offers us a way of returning to ourselves and reveals how one of the most secret, intimate experiences available to us is part of a path of return.

The longing for fusion – becoming ‘one fire’ – is in fact a stage on the way to the other end of sexual intercourse, which is completeness, distinction, knowledge of the self in its own burnished perfection.[19]

Radical Hospitality: Lothlorien

.

The1970s were a time when new ideas of community were being widely explored, and many projects were being set up as part of a general optimism for a more socially aware future. In The Knife Edge of Experience, published in 1972,[20] Rosemary explored the importance of community from a Christian perspective. She looked at the matter through St Paul’s letters to the Corinthians, addressing the community of the young church. Then, in 1974, with Algy and some of her now grown-up children (including my parents), she found a way to give her ideas practical expression in the establishment of a community in Scotland dedicated to a radical new way of living. The aim was to support people who had mental and physical health problems by inviting them to live beside others who were seeking a life that would connect them to God and the land. There would be no ‘patients’ and ‘therapists’; just people living together.

One of my own early memories of what was to become ‘Lothlorien’ [/] is of a gloomy day in Galloway when I was four years old. It was raining. We walked around a pile of logs, that lay on the ground in a woody clearing. The adults talked above my head and I was cold. That log pile became what, even now, is the largest log house in Europe, built to house the new community. The name Lothlorien had been given by some American film makers from whom the land had been bought. Rosemary and Algy kept it as my grandfather adored the Lord of the Rings – perhaps partly because he had met Tolkien at Cambridge – and he read The Hobbit to us all on dark winter evenings, when the house was being built and we lived in caravans. The name stuck partly because it referred to the special land protected by Galadriel’s magic – a forest into which evil could not enter without difficulty. Grandmama was no stranger to magic and miracles; in fact, she had written a book called Tales from Eternity: The World of Faerie and the Spiritual Search in 1973.[21]

Life in the community combined the ordinary and the extraordinary. We celebrated Mass on Sundays when Father Anthony Ross would come from Edinburgh and I witnessed the wonder of the large table laid for up to thirty or more people for the Sunday breakfast, with hot rolls, coffee and even eggs and bacon. There were wonderful celebrations, but also many arguments and terrible dramas. There was a prayer room in the house where people would meet to pray together, and a prayer hut in the young orchard where one could have time for silent, solitary contemplation. As a child I often made use of this special space to escape the confusion of growing up.

We pioneered self-sufficiency, growing our own food, as well as flowers in the garden, raising animals, making cheese and butter. I helped to care for the animals; I remember when I was about eight years old seeing the morning star like a message from God when I woke to ‘help’ milk the cows. All the children gathered whenever a cow was calving and witnessed the miracle of new life.

Rosemary supported the growing Lothlorien community in Scotland, both spiritually and financially through writing books and her lecture tours in America. Gradually her life in America called her into deeper connection with the people she had come to know and with whom she shared a Catholic sensibility. Eventually, another community was born, namely, Wellspring House, and she started to spend the majority of her time there. This was a huge change for everyone at Lothlorien, including her family and especially her younger children. She and Algy were always dear to one another but by that time the relationship was no longer a marriage.

The Lothlorien vision and the community continued to thrive because of the many people, including my own parents, who carried on its work, deeply committed to its therapeutic vision. In 1989, when Algy had to retire, it was passed on to the Buddhist Rokpa Trust and continues to support people with mental health challenges to realise their full potential.

Radical Hospitality: Wellspring House

.

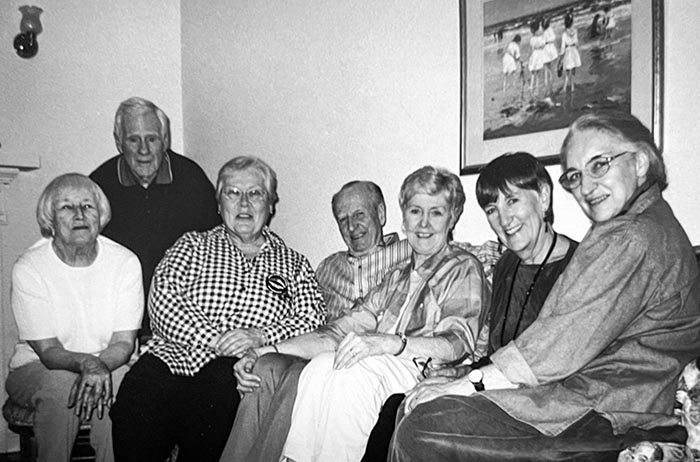

In April 1981 Rosemary and a group of six friends – including her beloved Nancy Schwoye, whom she married in 2011 – bought a wonderful old building in Massachusetts and established Wellspring House. Their shared vision was of home making and hospitality for people in need – to create a refuge for those, particularly women, who needed help to get back on their feet after becoming homeless or escaping abusive relationships. The property was a classic New England clapboard house built sometime after 1685 (notably it had been purchased in 1826 by Robert Freeman, the son of a former enslaved man) and needed extensive renovation.

In offering hospitality and care to homeless and abused women, Wellspring was creating the possibility of systemic change, finding new ways of responding to violence against women. In Rosemary’s writing we can feel her anger and see how her essential relationship with a passionate loving God is through helping other people. It is not enough to leave it to society.

The police brought a young woman to Wellspring about midnight. She had been beaten by her boyfriend and needed a safe place for the night. It turned out that the boyfriend who was drunk, had beaten her in her own apartment, for which she paid rent, and fallen asleep on her couch. She called the police because she was afraid of what would happen when he woke, and their response was to remove her (to Wellspring) and leave him on the couch. They did not remove him, even though it was her apartment. This is a good example of how society views women and property.[22]

I lived and volunteered in Wellspring for a few months during my late teenage years, and I benefited greatly from the experience. I made relationships with other residents, helped them care for their children, sometimes new-born babies. I enjoyed the big-hearted community, the sense of ‘can do’, that everything is possible. By that time, they had established independent but supported living accommodation in Gloucester (the local town) for homeless men as well as educational programmes for young women. The house was wonderfully lively but peaceful and well ordered, like a good home should be (see video right or below).

Video: Nancy Schwoyer and Rosemary Haughton: Reclaiming Home-Making; duration 10:50

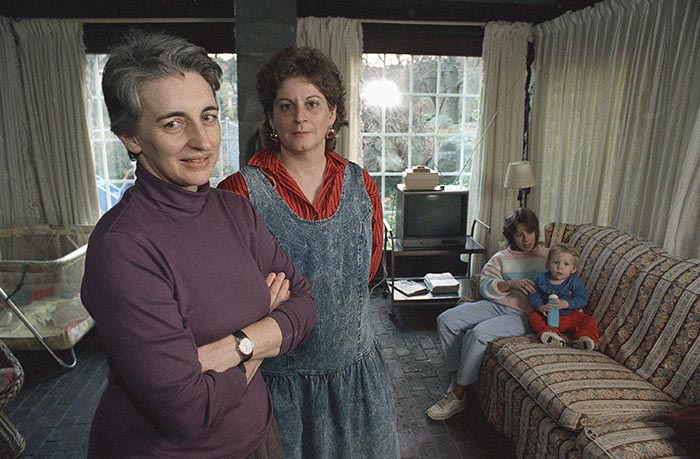

Rosemary Haughton, foreground, and Donna Loria, a housing specialist, in the living room of Wellspring house in 1987. A current resident and child are seen in background. Photograph: AP Photo/Shawn Henry/Alamy Stock Photo

In her last decade she wrote her final book with Nancy and their friend Kimberly French, about the Wellspring House project, entitled Radical Hospitality;

Radical comes from the Latin word for ‘rooted’. Hospitality comes from a Latin word that both means ‘host’ and ‘guest’ or even ‘stranger’. To practice hospitality, we aren’t just inviting friends to dinner or to come for the weekend. We are making our life decisions, in the place where we live, rooted in an attitude of openness. Such hospitality is about saying ‘Come in’ not only to people and ideas we feel comfortable with, but to strangers and even strange ideas. That isn’t always comfortable or even safe.[23]

The book, which was published posthumously, tells the story from the initial vision and its enactment through the hard lessons of change and ultimately passing the project on to new people. It has been widely praised as it articulates a model for a real solution to many of our societal problems.

Wellspring House was a haven from dominant social structures, collectively built on mutuality and a commitment to a sustainable community, both economically and spiritually. It is a model that can and should be replicated.[24]

Rosemary and Nancy shared with their friends a profound curiosity and asked the simple question; how can we help? Over time, with many, many volunteers and helpers and visionary people, Wellspring offered not only places to live but educational programmes:

Education is the key to the transformation of poverty. Of all the things we attempted – and there are so many – one of the best decisions we made was starting the education centre. It left a legacy of women, many of them formerly homeless, who transformed themselves into professionals, advocates and community leaders.[25]

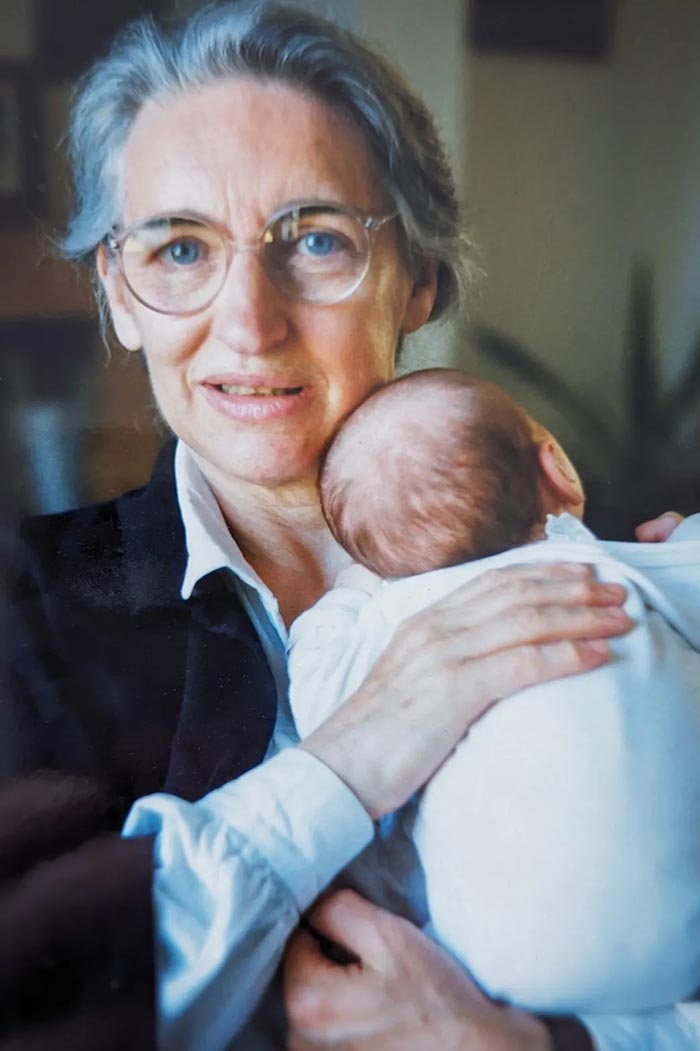

Rosemary with grandchild Bibi, 1997. Photograph courtesy Heidi Alexander [/]

A Lived Theology

.

Rosemary was always moved by people, by family, friendship and relationship. Her Catholic theology had to be lived to be ‘real’. For God to be experienced in it, it had to be tasted.

When I first became a Catholic I imagined ‘theology’ as a set of thick, bound copies on a shelf, like the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas. But theology, which comes from the Greek theos and logia, for god word, is built of words that are in daily use. So they change all the time, incorporating new influences, often unnoticed… and when we try to use them about God, or god, they are necessarily inadequate and actually deceptive. There are no words for God. The best we can do is to say what God is not, said Meister Eckhart, the great fourteenth-century German theologian and mystic. He was often in trouble with the inquisition for saying that God is nothing, language now easily recognised in Buddhist spirituality and theology.[26]

Wherever she lived, she created extraordinary places with wonderful gardens that produced nourishment for the whole human being; food for the body and beauty for the soul. The last of these was in Heptonsall, in Yorkshire, where she moved to with Nancy for the final decade of her life. The embodied and relational theology that she wrote and lived speaks to us now more than ever. In our confused times, with so much existential threat, it is surely in coming together in the largest aspects of ourselves and with trust in God, whatever our religion, that we can find the way to respond to the challenges we face.

To all who knew and loved her, to her family and friends, my grandmother gave a portion of her huge capacity for living, the power of believing in the goodness of life and the possibility of justice as well as the appreciation of what is immediately available to us all; radical love.

Image Sources (click to open)

Banner: Rosemary in 2013 at a family wedding. Photograph courtesy of the Haughton family.

Inset: Book cover of The Theology of Experience (later entitled The Knife Edge of Experience), 1972.

Other Sources (click to open)

[1] From a letter to Hugh Garvey, September 3, 1967, in Thomas Merton, Witness to Freedom: Letters in Times of Crisis, ed. William H. Shannon (Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1994), p. 174.

[2] ELIZABETH LULING, Do Not Disturb, The Adventures of M’m and Teddy (Oxford University Press, 1937), p. 7.

[3] EILISH RYAN, Rosemary Haughton: Witness to Hope, (Sheed & Ward, 1997), p. 6.

[4] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON & NANCY SCHWOYER with KIMBERLY FRENCH, Radical Hospitality, (Peter Lang, 2024), p. 22.

[5] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, Trying to be Human (Templegate Sringfield Illinois,1966).

[6] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, The Transformation of Man (Geoffrey Chapman, 1967).

[7] Ibid, p. 7.

[8] Ibid, p. 108.

[9] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, ‘Re-discovering Church’, Marianist Award Lectures (1987), p.18; available at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/uscc_marianist_award/18

[10] Ibid, p. 53.

[11] THOMAS MERTON, 1967. From the Merton Archive. The whole correspondence can be seen at https://merton.org/research/correspondence/y1.aspx?id=866

[12] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, 1967. Ibid.

[13] THOMAS MERTON, The Other Side of the Mountain: The End of the Journey. Journals, vol. 7: 1967-1968, ed. Patrick Hart (HarperCollins, 1998), p. 4. Quoted by James Robinson in ‘The Age of the Rosemarys’; a presentation given at the 17th General Meeting of the International Thomas Merton Society, June 2021. For the full text see: https://merton.org/ITMS/Annual/34/Robinson120-128.pdf

[14] From a letter to Hugh Garvey, September 3, 1967, in Thomas Merton, Witness to Freedom: Letters in Times of Crisis, p. 174.

[15] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, The Drama of Salvation, (Seabury 1975), p.10–11.

[16] PETER BROOK, The Empty Space (Penguin Modern Classics, 1968), quoted in The Drama of Salvation, p. 118.

[17] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, The Drama of Salvation, p. 118–119.

[18] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, The Passionate God, (Paulist Press, 1981).

[19] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, The Knife Edge of Experience (Darton, Longman & Todd, 1972), p. 134.

[20] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, The Knife Edge of Experience (Darton, Longman & Todd, 1972).

[21] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, Tales from Eternity: The World of Faerie and the Spiritual Search (George Allan & Unwin, 1973).

[22] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON, Song in a Strange Land (Harlequin Paperback. 1987) p. 23.

[23] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON & NANCY SCHWOYER with KIMBERLY FRENCH, Radical Hospitality, p. 5

[24] RUTH McCAMBRIDGE of Non-profit Quarterly https://www.waterstones.com/book/radical-hospitality/nancy-schwoyer/rosemary-haughton/9781803744261

[25] ROSEMARY HAUGHTON & NANCY SCHWOYER with KIMBERLY FRENCH, Radical Hospitality, p. 147.

[26] Ibid, pp. 22–23.

Phoebe Ryrko (www.phoeberyrko.co.uk) is an artist who studied fine art painting at Bath College of Higher Education and gained a masters in Lighting Design at Edinburgh Napier University. Her creative work as an artist is a devotional practice; an active exploration into the means by which the hidden interior can be felt through gestures made in paint. She is the daughter of the painter Benet Haughton and the granddaughter of Rosemary Haughton

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

——————————————

——————————————

——————————————

Video: Jim Robinson: Thomas Merton’s Engagement with Rosemary Radford Ruether and Rosemary Haughton; duration 21:08

Video: Nancy Schwoyer and Rosemary Haughton: Reclaiming Home-Making; duration 10:50

FOLLOW AND LIKE US

If you enjoyed reading this article

Please leave a comment below.

Please also consider making a donation to support the work of Beshara Magazine. The magazine relies entirely on voluntary support. Donations received through this website go towards editorial expenses, eg. image rights, travel expenses, and website maintenance and development costs.

READ MORE IN BESHARA MAGAZINE

The Engaged Contemplative Spirituality of Thomas Merton

Jim Griffin surveys the life and work of the great 20th century visionary who pioneered a new understanding of Christian meditation and interfaith dialogue

Painting and the Contemplative Life

Artist and psychotherapist Benet Haughton talks about the spiritual vision that underpins his life and work

Dante, Erotic Love and the Path to God

On the 700-year anniversary of The Divine Comedy, Mark Vernon explores a pivotal moment of transformation in the Purgatorio

Love Will Not Be Idle: Mysticism and Activism

Jane Clark reports on a timely conference put on by the Mystical Theology Network, and talks to its organiser, Dr Louise Nelstrop

READERS’ COMMENTS

1

What an incredible woman and history of her amazing life! Thank you so much for sharing her life with all of us. I’m honored to have called her friend.